Journal of Forensic & Investigative Accounting Volume 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

N:\Jsternberg\Reuben\Sentencing Memo.Wpd

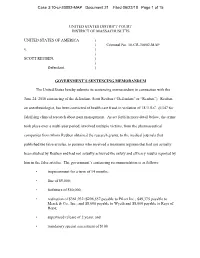

Case 3:10-cr-30002-MAP Document 21 Filed 06/22/10 Page 1 of 15 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) ) Criminal No. 10-CR-30002-MAP v. ) ) SCOTT REUBEN, ) ) Defendant. ) GOVERNMENT’S SENTENCING MEMORANDUM The United States hereby submits its sentencing memorandum in connection with the June 24, 2010 sentencing of the defendant, Scott Reuben (“Defendant” or “Reuben”). Reuben, an anesthesiologist, has been convicted of health care fraud in violation of 18 U.S.C. §1347 for falsifying clinical research about pain management. As set forth in more detail below, the crime took place over a multi-year period, involved multiple victims, from the pharmaceutical companies from whom Reuben obtained the research grants, to the medical journals that published the false articles, to patients who received a treatment regimen that had not actually been studied by Reuben and had not actually achieved the safety and efficacy results reported by him in the false articles. The government’s sentencing recommendation is as follows: • imprisonment for a term of 14 months; • fine of $5,000; • forfeiture of $50,000; • restitution of $361,932 ($296,557 payable to Pfizer Inc.; $49,375 payable to Merck & Co., Inc.; and $8,000 payable to Wyeth and $8,000 payable to Rays of Hope; • supervised release of 2 years; and • mandatory special assessment of $100. Case 3:10-cr-30002-MAP Document 21 Filed 06/22/10 Page 2 of 15 As set forth below, the government’s recommendation for a sentence of incarceration of 14 months is below the applicable guideline range (18-24 months) and is consonant with the factors of 18 U.S.C. -

Pain Management After Elective Hallux Valgus Surgery: a Prospective Randomized Double-Blind Study Comparing Etoricoxib and Tramadol

Pain Medicine Section Editor: Spencer S. Liu Pain Management After Elective Hallux Valgus Surgery: A Prospective Randomized Double-Blind Study Comparing Etoricoxib and Tramadol Metha Brattwall, MD,* Ibrahim Turan, MD, PhD,† and Jan Jakobsson‡ BACKGROUND: Pain is a common complaint after day surgery, and there is still a controversy surrounding the use of selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors. In the present prospective, randomized, double-blind study we compared pain management with a selective (COX-2) inhibitor (etoricoxib) with pain management using sustained-release tramadol after elective hallux valgus surgery. METHODS: One hundred ASA 1 to 2 female patients were randomized into 2 groups of 50 patients each; oral etoricoxib 120 mg ϫ 1 ϫ IV ϩ 90 mg ϫ 1 ϫ day V–VII and oral tramadol sustained-release 100 mg ϫ 2 ϫ VII. Pain, pain relief, satisfaction with pain management, and need for rescue medication were evaluated during the first 7 postoperative days. A computed tomography scan evaluating bone healing was performed 12 weeks after surgery. A clinical evaluation of outcome (healing, mobility, and patient-assessed satisfaction) was performed 16 weeks after surgery. RESULTS: Two patients withdrew before discharge from the hospital. Ninety-eight patients, 81 ASA 1 and 17 ASA 2 (82 nonsmokers and 14 smokers), mean age 49 years (19–65), weight 64 (47–83) kg, and height 167 (154–183) cm were evaluated. Overall pain was well managed, but the mean visual analog scale (VAS) was significantly lower among etoricoxib patients evaluated during the entire 7-day period studied (12.5 Ϯ 8.3 vs. -

Anesthesiologist Sentenced to 6 Months for Faked Research Robert Lowes

Accessed on 20Feb12 from url: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/724381 From Medscape Medical News Anesthesiologist Sentenced to 6 Months for Faked Research Robert Lowes June 29, 2010 — Anesthesiologist Scott Reuben, MD, who pled guilty earlier this year to falsifying research on the use of analgesics such as celecoxib (Celebrex; Pfizer) and rofecoxib (Vioxx; Merck) for postoperative pain management, was sentenced in a Boston, Massachusetts, federal court last week to 6 months in prison for healthcare fraud. In addition, the prominent 51-year-old physician must forfeit $50,000 in assets as well as pay a $5000 fine and $361,932 in restitution to pharmaceutical companies that financed his research, including $296,557 to Pfizer. Pfizer paid for a clinical study of Dr. Reuben's on the perioperative use of celecoxib as part of multimodal analgesia for outpatient anterior cruciate ligament reconstructive surgery. Dr. Reuben reported in 2 articles published in the journal Anesthesia & Analgesia that he had treated 200 patients in the trial — 100 with placebo and 100 with celecoxib — and achieved success with multimodal analgesia therapy. However, Dr. Reuben later admitted that he had not enrolled any patients in the trial but, instead, had simply made up the findings. Anesthesia & Analgesia and other medical journals have retracted more than 20 articles by Dr. Reuben containing fabricated data, according to the publication Anesthesiology News. Client's Bipolar Disorder Cited as Reason Against Imprisonment Dr. Reuben was the former chief of the acute pain clinic at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Massachusetts. In addition to conducting research, Dr. Reuben spoke frequently at medical conferences and continuing medical education events, as well as in "promotional settings," about administering celecoxib and rofecoxib in combination with other analgesics to reduce postoperative pain, according to court documents. -

Researchers Behaving Badly ANZCA BULLETIN

september 2012 anZCa BulleTin Researchers behaving badly plus: a vision for The anZCa 10 years College: anZCa CurriCulum on from sTraTegiC plan revision 2013 The Bali 2013-2017 updaTe BomBing 8 ANZCA Strategic Plan 2013-2017 The College has developed a strategic plan for the next fi ve years. ANZCA Strategic Plan 2013-2017 Advancing anaesthesia, improving patient care 24 The revised curriculum and you Next year’s training program will benefi t all. 22 Bali bombing 10-year anniversary October 13, 2002 started as an ordinary day at the Royal Darwin Hospital but things soon changed. ANZCA Bulletin Medical editor: Dr Michelle Mulligan Contacts Editor: Clea Hincks Head offi ce 630 St Kilda Road, Melbourne Production editor: Liane Reynolds Victoria 3004, Australia Sub editor: Kylie Miller Telephone +61 3 9510 6299 Facsimile +61 3 9510 6786 Design: Christian Langstone [email protected] Advertising manager: Mardi Mason www.anzca.edu.au Submitting letters and other material Faculty of Pain Medicine We encourage the submission of letters, news and Telephone +61 3 8517 5337 feature stories. Please contact ANZCA Bulletin Editor, [email protected] Clea Hincks at [email protected] if you would like Copyright: Copyright © 2012 by the Australian The Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists to contribute. Letters should be no more that 300 words and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, all rights (ANZCA) is the professional medical body in Australia and must contain your full name, address and a daytime reserved. None of the contents of this publication may and New Zealand that conducts education, training and telephone number. -

Revista De La Sociedad Española Del Dolor

Rev Soc Esp Dolor. 2009;16(7):371-372 VOLUMEN 16, N.º 7 OCTUBRE 2009 Editorial Discólisis percutánea con ozono: Medicina del dolor basada en la evidencia: nuestra experiencia lo bueno, lo malo, lo feo y lo peor M. Castro, L. Cánovas, J. Martínez, A. Pastor, C. Nebreda y L. Aliaga 371 I. Segado, F. Rocha y C. Izquierdo 405 REVISTA DE LA SOCIEDAD Artículo especial Originales Estudio de utilización de analgésicos Aspectos medicolegales y bioéticos opiáceos en un hospital general de la cirugía instrumentada de la universitario columna lumbar degenerativa. P. Gómez Salcedo, A. Herrero Ambrosio Implicaciones en el manejo del dolor y J.M. Muñoz y Ramón 373 crónico F.J. Robaina Padrón 410 Eficacia analgésica de la asociación duloxetina más pregabalina en el dolor Carta al director neuropático: experiencia en 60 casos Opiáceos en el dolor musculoesquelético L. Cánovas Martínez, I. Gómez Gutiérrez, crónico. ¿Estamos contra ellos? M. Castro Bande, E. Peralta Espinosa, F.J. Robaina Padrón 415 J.M. Prieto Gutiérrez e I. Segado Jiménez 381 Dolor en la prensa Prevalencia de dolor neuropático La fibromialgia provoca un gasto ESPAÑOLA DEL DOLOR en pacientes con cáncer sin relación de 10.000 euros por paciente al año 417 con el tratamiento oncológico previo R. García-Hernández, I. Failde, A. Pernia, Formacion continuada 419 E. Calderón y L.M. Torres 386 Boletín de la Sociedad Española Notas clínicas del Dolor Bloqueo tricompartimental del hombro Noticias, Congresos y Cursos 420 doloroso: estudio preliminar D. Abejón, M. Madariaga, J. del Saz, B. Alonso, A. Martín y M. Camacho 399 www.elsevier.es/resed Actividad acreditada CGCOM en base a la encomienda de gestión concedida por los Ministerios de Sanidad y Política Social y Ministerio de Educación al Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Médicos con SEAFORMEC 2,9 CRÉDITOS equivalentes a 12 horas lectivas. -

How Do You Know It Is True? Integrity in Research and Publications: AOA Critical Issue Joseph A

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2015 How do you know it is true? integrity in research and publications: AOA critical issue Joseph A. Buckwalter University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics Vernon T. Tolo Keck School of Medicine at University of Southern California Regis J. O'Keefe Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Recommended Citation Buckwalter, Joseph A.; Tolo, Vernon T.; and O'Keefe, Regis J., ,"How do you know it is true? integrity in research and publications: AOA critical issue." The ourj nal of bone and joint surgery.97,1. e2. (2015). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/3663 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. e2(1) COPYRIGHT Ó 2015 BY THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY,INCORPORATED AOA Critical Issues How Do You Know It Is True? Integrity in Research and Publications AOA Critical Issues Joseph A. Buckwalter, MS, MD, Vernon T. Tolo, MD, and Regis J. O’Keefe, MD, PhD High-quality medical care is the result of clinical decisions based upon scientific principles garnered from basic, translational, and clinical research. Information regarding the natural history of diseases and their responses to various treatments is in- troduced into the medical literature through the approximately one million PubMed journal articles published each year. -

Research Misconduct and the Law: Intervening to Name, Shame and Deter

Research Misconduct and the Law: Intervening to Name, Shame and Deter Ian Freckelton QC Crockett Chambers, Melbourne, Australia; Professorial Fellow in Law and Psychiatry, University of Melbourne, Australia Editor, Journal of Law and Medicine [email protected] See I Freckelton, Scholarly Misconduct and the Law (OUP, 2016) Criminal Law Invoked by the state to punish, deter and protect Compensation Actions Providing encouragement to victims to come forward and to ventilate concerns about research integrity, and recognising that by doing so they are likely to suffer losses. Also deters. Research Misconduct Office of Research Integrity: “Research misconduct means fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results” The Lens of the Law on Research Misconduct Prosecutions for fraud: a form of white collar crime Appeals & judicial review Injunctions Workplace dismissal litigation Defamation actions Disciplinary/registration/licensure proceedings Harassment & discrimination actions Compensation actions (tort & qui tam) Contextualising Research Fraud by Reference to Criminal Law Undertaken by economically and otherwise privileged Premeditatedly done using knowledge and opportunity Has foreseeably adverse consequences for others – direct & indirect victims Undertaken for gain – career, economic, kudos etc Fundamentally dishonest: manipulates/exploits funding – directly/indirectly Tom Nichols, The Death of Expertise (2017) When experts lie, they endanger not only their -

Vol. 8, No. 9, September 2012 “Happy Trials to You” Clinical Research

Vol. 8, No. 9, September 2012 “Happy Trials to You” Clinical Research Fraud: The Case of the Errant Investigator By Barbara Burkott Managing pain during and after orthopedic surgery can be a major challenge. Multimodal analgesia addresses the challenge by employing two or more analgesic agents that affect different pain mechanisms. In addition to reducing pain, multimodal analgesia also reduces side effects by allowing the use of lower dosages of each agent. Dr. Scott Reuben was Professor of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine at Tufts University in Boston, Massachusetts, and Chief of Acute Pain at Baystate Medical Center (BMC) in Springfield, Massachusetts. As the leader in research on multimodal analgesia for post- operative pain management, especially in orthopedic surgery, Dr. Ruben published 21 journal articles on the topic, starting in 1996.1 These articles were based on several investigator-initiated clinical studies conducted at BMC. Dr. Reuben’s work came under suspicion in 2008, when a routine review at BMC noticed that studies described in two articles did not appear to have received IRB approval. Further investigation revealed forged signatures by presumed co-authors and imaginary studies that enrolled imaginary subjects. As a result, BMC retracted Dr. Reuben’s articles, his employer terminated his employment, the FDA conducted an inspection and debarred him, he lost his medical license, and a federal court sentenced him in 2010 to six months in prison and $415,000 in financial penalties. The scientific foundation for multimodal analgesia was shattered. Remediation When the fraud was discovered, Dr. Reuben’s colleagues (including the author) expressed shock and disbelief: He could not have done this! We trusted him as a physician, as a colleague. -

Moral Authority in Scientific Research Evelyn Sowers PHIL

Moral Authority in Scientific Research Evelyn Sowers PHIL 499: Senior Thesis Carroll College 2019 2 Abstract This paper addresses the issue of applying moral guidelines to modern scientific research and who or what should have the authority to do so. It examines the role of morality in scientific research, and makes the argument that moral authority over scientific research should come from the scientific community. This argument is based on two premises: (1) that the scientific community is of sufficient moral character to guide the direction of scientific research and (2) that the scientific community has sufficient expertise to make informed moral decisions about scientific research. 3 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 4 Moral Authority .......................................................................................................... 7 Morality in Scientific Research .................................................................................... 8 2. MORALITY WITHIN THE SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITY .................................................. 11 Science ...................................................................................................................... 11 The Scientific Community .......................................................................................... 14 Moral Characteristics of the Scientific Community ..................................................... 19 Moral Accountability in -

Managing Physician-Company Conflict of Interest

DRUG AND MEDICAL DEVICE The Emerging Legal Regime Managing Physician-Company By David L. Ferrera Conflict of Interest and Dawn M. Curry The need to justify Pharmaceutical and medical device companies cannot medical care as cost- exist without physicians to prescribe their products. But effective raises concerns what happens when an intermediary becomes a collabora- about how physician- tor? The law of conflict of interest as it affects drug and medical device companies and physicians panies, and new claims in civil product company relationships spans multiple practice areas that clients liability litigation that call into question and counsel alike should understand to physicians’ roles in clinical research, in may affect approvals of ensure a uniform approach to business and dispensing medical advice, and in pro- litigation decisions. viding treatment to patients. As the legal certain drugs and devices. Disclosure of the close connections framework unfolds, physicians and drug between the pharmaceutical and medi- and medical device companies can expect cal device industries and physicians has to face heightened scrutiny and increased spurred growing federal and state level risks of civil and criminal legal actions. backlashes against such relationships. Actions by Congress, the U.S. Department Federal Government Enforcement of Justice, several state legislatures and Federal prosecutors have become much attorneys general, and civil courts have more aggressive in employing a number of all contributed to a new legal framework legal tools and in casting an ever wider net governing financial relationships between to punish and deter perceived corruption physicians and drug and medical device among physicians and pharmaceutical and companies. -

Tattered Threads

Editorial Tattered Threads Steven L. Shafer, MD Eugene Viscusi gave his typically superb talk on perioperative analgesic management last December at the Post Graduate Assembly in New York. Midway through his talk, he presented a series of articles from Anesthesia & Analgesia by Dr. Scott Reuben showing the long-term beneficial effects of perioperative nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug administration. I lis- tened in silent horror, knowing that the articles in Anesthesia & Analgesia were likely fraudulent. I had known for months of an ongoing investiga- tion at Baystate Medical Center. However, because of the confidentiality of the proceedings, and the lack of a formal statement of findings, I could not say anything. I sat silently as Dr. Viscusi misinformed his audience based on fraudulent work published in Anesthesia & Analgesia. Should I have spoken up, violating the confidentiality of Baystate’s investigation, and besmirching the reputation of a prominent investigator based upon unsubstantiated allegations? Or did I do the right thing keeping quiet, knowing that physicians in the audience might alter their therapy and expose patients to unnecessary risks based on fabricated data? Richard Feynman1 eloquently observed that “nature uses only the longest threads to weave her patterns, so that each small piece of her fabric reveals the organization of the entire tapestry.” Scientists and clinicians are weavers as well, examining the incremental bits of knowledge published in the peer-reviewed literature for trends and patterns. We weave these bits of evidence into our knowledge of physical reality. It does not matter whether the goal is to understand planetary motion, evolution, global warming, or perioperative analgesia; the interlocking of many threads of evidence gives beauty, elegance, and intellectual strength to the interwo- ven tapestry of human understanding. -

Thesis Reference

Thesis Role of systematic reviews in the identification and prevention of poor quality research and scientific misconduct: random reflections based on anaesthesiologic cases ELIA, Nadia Abstract Research in clinical medicine often suffers from poor methodological quality and is sometimes based on fraudulent data, which may bias the conclusions of systematic reviews. This dissertation develops the idea that not all research malpractices and misconduct threaten the scientific knowledge, nor may they all bias the conclusions of systematic reviews to the same extent, but rather that the strict procedures applied during proper systematic reviewing actually should make systematic reviews robust to some common errors and misconduct. Moreover, well-performed systematic reviews could become part of the solution to the problem by providing clear research agendas and by providing important methodological information that may be used for future research. Furthermore, systematic reviewers may correct the published literature after having identified errors during critical appraisal of articles, and they may even play the role of whistle-blowers by identifying new, yet unrecognised, cases of misconducts. Reference ELIA, Nadia. Role of systematic reviews in the identification and prevention of poor quality research and scientific misconduct: random reflections based on anaesthesiologic cases. Thèse de privat-docent : Univ. Genève, 2017 DOI : 10.13097/archive-ouverte/unige:92532 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:92532 Disclaimer: layout