Social Movements As Information Ecologies: Exploring the Coevolution of Multiple Internet Technologies for Activism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Town Hall Constituent Questions & Answers

Council Member Helen Rosenthal’s Town Hall 2018 April 26, 2018 6pm-9pm Marlene Meyerson JCC Manhattan 334 Amsterdam Avenue YOU ASK, THE AGENCIES ANSWER! HelenRosenthal.com District Office: (212) 873-0282 Legislative Office: (212) 788-6975 HelenRosenthal.com District Office: (212) 873-0282 Legislative Office: (212) 788-6975 3 Contents Tonight’s Program …….. Agencies in Attendance ….. Special Thanks…. Contact Information…. Notes for Readers …. Constituent Questions for Agencies …. Transportation…. Small Businesses…. Neighborhood…. Schools…. Environmental Issues…. Parks… Sanitation…. Bikes/Pedestrian Safety…. Housing…. Buildings… Homelessness…. Policing… Miscellaneous….. Utilities…… HelenRosenthal.com District Office: (212) 873-0282 Legislative Office: (212) 788-6975 4 Town Hall Program Opening Remarks by Council Member Helen Rosenthal Announcement of Winning Projects in District 6 Participatory Budgeting Introduction of Panelists Responses from City Agencies to Submitted Questions Questions from the Audience HelenRosenthal.com District Office: (212) 873-0282 Legislative Office: (212) 788-6975 5 Agencies in Attendance Community Board 7 (CB7) ……………..….....…………………………. 212-362-4008 (Roberta Semer, Board Chair) Con Edison ……………………....................................................................... 800-752-6633 (Kimberly Williams, Director of Manhattan Public Affairs) Department of Buildings (DOB) ………………………………............ 212-566-5000 (Byron Munoz, Intergovernmental & Community Affairs) Department of Education (DOE) …................................................. -

Bronx Brooklyn Manhattan Queens

CONGRATULATIONS OCTOBER 2018 CAPACITY FUND GRANTEES BRONX Concrete Friends – Concrete Plant Park Friends of Pelham Parkway Jackson Forest Community Garden Jardín de las Rosas Morrisania Band Project – Reverend Lena Irons Unity Park Rainbow Garden of Life and Health – Rainbow Garden Stewards of Upper Brust Park – Brust Park Survivor I Am – Bufano Park Teddy Bear Project – Street Trees, West Farms/Crotona Woodlawn Heights Taxpayers Association – Van Cortlandt Park BROOKLYN 57 Old Timers, Inc. – Jesse Owens Playground Creating Legacies – Umma Park Imani II Community Garden NYSoM Group – Martinez Playground Prephoopers Events – Bildersee Playground MANHATTAN The Dog Run at St. Nicholas Park Friends of St. Nicholas Park (FOSNP) Friends of Verdi Square Muslim Volunteers for New York – Ruppert Park NWALI - No Women Are Least International – Thomas Jefferson Park Regiven Environmental Project – St. Nicholas Park Sage’s Garden QUEENS Bay 84th Street Community Garden Elmhurst Supporters for Parks – Moore Homestead Playground Forest Park Barking Lot Friends of Alley Pond Park Masai Basketball – Laurelton Playground Roy Wilkins Pickleball Club – Roy Wilkins Recreation Center STATEN ISLAND Eibs Pond Education Program, Inc. (Friends of) – Eibs Pond Park Friends of Mariners Harbor Parks – The Big Park Labyrinth Arts Collective, Inc. – Faber Pool and Park PS 57 – Street Trees, Park Hill CITYWIDE Historic House Trust of New York City Generous private support is provided by the Altman Foundation and the MJS Foundation. Public support is provided by the NYC Council under the leadership of Speaker Corey Johnson through the Parks Equity Initiative. . -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX ABC Television Studios 152 Chrysler Building 96, 102 Evelyn Apartments 143–4 Abyssinian Baptist Church 164 Chumley’s 66–8 Fabbri mansion 113 The Alamo 51 Church of the Ascension Fifth Avenue 56, 120, 140 B. Altman Building 96 60–1 Five Points 29–31 American Museum of Natural Church of the Incarnation 95 Flagg, Ernest 43, 55, 156 History 142–3 Church of the Most Precious Flatiron Building 93 The Ansonia 153 Blood 37 Foley Square 19 Apollo Theater 165 Church of St Ann and the Holy Forward Building 23 The Apthorp 144 Trinity 167 42nd Street 98–103 Asia Society 121 Church of St Luke in the Fields Fraunces Tavern 12–13 Astor, John Jacob 50, 55, 100 65 ‘Freedom Tower’ 15 Astor Library 55 Church of San Salvatore 39 Frick Collection 120, 121 Church of the Transfiguration Banca Stabile 37 (Mott Street) 33 Gangs of New York 30 Bayard-Condict Building 54 Church of the Transfiguration Gay Street 69 Beecher, Henry Ward 167, 170, (35th Street) 95 General Motors Building 110 171 City Beautiful movement General Slocum 70, 73, 74 Belvedere Castle 135 58–60 General Theological Seminary Bethesda Terrace 135, 138 City College 161 88–9 Boathouse, Central Park 138 City Hall 18 German American Shooting Bohemian National Hall 116 Colonnade Row 55 Society 72 Borough Hall, Brooklyn 167 Columbia University 158–9 Gilbert, Cass 9, 18, 19, 122 Bow Bridge 138–9 Columbus Circle 149 Gotti, John 40 Bowery 50, 52–4, 57 Columbus Park 29 Grace Court Alley 170 Bowling Green Park 9 Conservatory Water 138 Gracie Mansion 112, 117 Broadway 8, 92 Cooper-Hewitt National Gramercy -

2018 CCPO Annual Report

Annual Concession Report of the City Chief Procurement Officer September 2018 Approximate Gross Concession Registration Concession Agency Concessionaire Brief Description of Concession Revenues Award Method Date/Status Borough Received in Fiscal 2018 Concession property is currently used for no other Department of purpose than to provide waterborne transportation, Citywide James Miller emergency response service, and to perform all Sole Source $36,900 2007 Staten Island Administrative Marina assosciated tasks necessary for the accomplishment Services of said purposes. Department of DCAS concession property is used for no other Citywide Dircksen & purpose than additional parking for patrons of the Sole Source $6,120 10/16/2006 Brooklyn Administrative Talleyrand River Café restaurant. Services Department of Citywide Williamsburgh Use of City waterfront property for purposes related to Sole Source $849 10/24/2006 Queens Administrative Yacht Club the operation of the yacht club. Services Department of Skaggs Walsh owns property adjacent to the Citywide Negotiated Skaggs Walsh permitted site. They use this property for the loading $29,688 7/10/2013 Queens Administrative Concession and unloading of oil and accessory business parking. Services Department of Concession property is currently used for the purpose Citywide Negotiated Villa Marin, GMC of storing trailers and vehicle parking in conjunction $74,269 7/10/2013 Staten Island Administrative Concession with Villa Marin's car and truck dealership business. Services Department of Concession -

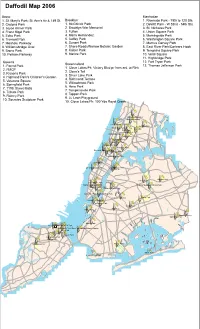

Daffodil Map 2006

Daffodil Map 2006 Bronx Manhattan 1. St. Mary's Park; St. Ann's Av & 149 St. Brooklyn 1. Riverside Park - 79th to 120 Sts. 2. Crotona Park 1. McGolrick Park 2. DeWitt Park - W 52nd - 54th Sts. 3. Joyce Kilmer Park 2. Brooklyn War Memorial 3. St. Nicholas Park 4. Franz Sigel Park 3. Fulton 4. Union Square Park 5. Echo Park 4. Maria Hernandez 5. Morningside Park 6. Tremont Park 5. Coffey Park 6. Washington Square Park 7. Mosholu Parkway 6. Sunset Park 7. Marcus Garvey Park 8. Williamsbridge Oval 7. Shore Roads/Narrow Botanic Garden 8. East River Park/Corlears Hook 9. Bronx Park 8. Kaiser Park 9. Tompkins Square Park 10. Pelham Parkway 9. Marine Park 10. Verdi Square 11. Highbridge Park Queens 12. Fort Tryon Park Staten Island 1. Forest Park 13. Thomas Jefferson Park 1. Clove Lakes Pk; Victory Blvd pr from ent. to Rink 2. FMCP 2. Clove's Tail 3. Kissena Park 3. Silver Lake Park 4. Highland Park's Children's Garden 4. Richmond Terrace 5. Veterans Square 5. Willowbrook Park 6. Springfield Park 6. Hero Park 7. 111th Street Malls 7. Tompkinsville Park 8. Tribute Park 8. Tappen Park 9. Rainey Park 9. Lt. Leah Playground 10. Socrates Sculpture Park 10. Clove Lakes Pk: 100 Yds Royal Creek Williamsbridge Oval Mosholu Parkway Fort Tryon Park Pelham Pkwy Highbridge Park Bronx Park Echo Park Tremont Park Highbridge Park Crotona Park Joyce Kilmer Park Franz Sigel Park St Nicholas Park St Mary's Park Riverside PMaorkrningside Park Marcus Garvey Park Thomas Jefferson Park Verdi Square De Witt Clinton Park Socrates Sculpture Garden Rainey Park Kissena Park 111th Street Malls Union Square Park Washington Square Park Flushing Meadows Corona Park Tompkins Square Park Monsignor Mcgolrick Park East River Park/Corlears Hook Park Maria Hernandez Park Forest Park Brooklyn War Memorial Fort Greene Park Highland Park Coffey Park Fulton Park Veterans Square Springfield Park Sunset Park Richmond TLetr.ra Nceicholaus Lia Plgd. -

City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011)

City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011) Borou Block Lot Address Parcel Name gh 1 2 1 4 SOUTH STREET SI FERRY TERMINAL 1 2 2 10 SOUTH STREET BATTERY MARITIME BLDG 1 2 3 MARGINAL STREET MTA SUBSTATION 1 2 23 1 PIER 6 PIER 6 1 3 1 10 BATTERY PARK BATTERY PARK 1 3 2 PETER MINUIT PLAZA PETER MINUIT PLAZA/BATTERY PK 1 3 3 PETER MINUIT PLAZA PETER MINUIT PLAZA/BATTERY PK 1 6 1 24 SOUTH STREET VIETNAM VETERANS PLAZA 1 10 14 33 WHITEHALL STREET 1 12 28 WHITEHALL STREET BOWLING GREEN PARK 1 16 1 22 BATTERY PLACE PIER A / MARINE UNIT #1 1 16 3 401 SOUTH END AVENUE BATTERY PARK CITY STREETS 1 16 12 MARGINAL STREET BATTERY PARK CITY Page 1 of 1390 09/28/2021 City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011) Agency Current Uses Number Structures DOT;DSBS FERRY TERMINAL;NO 2 USE;WATERFRONT PROPERTY DSBS IN USE-TENANTED;LONG-TERM 1 AGREEMENT;WATERFRONT PROPERTY DSBS NO USE-NON RES STRC;TRANSIT 1 SUBSTATION DSBS IN USE-TENANTED;FINAL COMMITMNT- 1 DISP;LONG-TERM AGREEMENT;NO USE;FINAL COMMITMNT-DISP PARKS PARK 6 PARKS PARK 3 PARKS PARK 3 PARKS PARK 0 SANIT OFFICE 1 PARKS PARK 0 DSBS FERRY TERMINAL;IN USE- 1 TENANTED;FINAL COMMITMNT- DISP;LONG-TERM AGREEMENT;NO USE;WATERFRONT PROPERTY DOT PARK;ROAD/HIGHWAY 10 PARKS IN USE-TENANTED;SHORT-TERM 0 Page 2 of 1390 09/28/2021 City-Owned Properties Based on Suitability of City-Owned and Leased Property for Urban Agriculture (LL 48 of 2011) Land Use Category Postcode Police Prct -

Virtual Verdi

VIRTUAL VERDI VERDI, VERDI, AND MORE VERDI American Institute for Verdi Studies https://www.nyu.edu/projects/verdi/AIVSbackground.html Istituto Nazionale di Studi Verdiani (National Institute for Verdi Studies) https://www.studiverdiani.it/ (Italian Original) https://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=it&u=https://www.studiverdiani.it/&prev=search (English Translation) Verdi 200 http://www.giuseppeverdi.it/en/ “Verdi and Milan,” Lecture by Professor Roger Parker, Gresham College, May 14, 2007 https://www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/verdi-and-milan “Discovering Verdi” Series of BBC radio programs on Verdi and his Operas https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01nrbn9 Giuseppe Verdi National Museum http://www.bussetolive.com/en/poi/museo-nazionale-giuseppe-verdi-villa-pallavicino/ PLACES ASSOCIATED WITH VERDI Verdi Birthplace http://www.bussetolive.com/en/poi/verdi-birthplace/ Casa Barezzi Museum http://www.bussetolive.com/en/poi/museo-casa-barezzi/ Milan Conservatory (Giuseppe Verdi Conservatory of Music, Milan, Italy) http://www.consmilano.it/ (Italian Original) www.translatetheweb.com/?ref=SERP&br=ro&mkt=en- US&dl=en&lp=IT_EN&a=http%3a%2f%2fwww.consmilano.it%2f (English Translation) La Scala Opera House, Milan, Italy http://www.teatroallascala.org/en/index.html Museum of La Scala Opera House, Milan, Italy http://www.museoscala.org/en/ Villa Verdi http://www.bussetolive.com/en/poi/villa-verdi/ CONTEMPORARY OPINIONS OF VERDI The Musical World (February 27, 1847), page 151 (See specifically the boxed section) https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_FJMPAAAAYAAJ/page/n137/mode/1up -

PATROL BOROUGH MANHATTAN SOUTH PCT. Location Sponsors Time 1 ZUCCOTTI PARK 1St Pct. Comm. Council 1800 Liberty Street Betw. Broa

PATROL BOROUGH MANHATTAN SOUTH PCT. Location Sponsors Time 1 ZUCCOTTI PARK 1st Pct. Comm. Council 1800 Liberty Street betw. Broadway to & Church St. 2000 5 COLUMBUS PARK 5 Pct. Comm. Council 1600 betw. Baxter/Mulberry Sts. HealthPlus to Worth/Mosco Sts. 2000 6 FATHER DEMO SQUARE 6 Pct. Comm. Council 1830 6th Avenue betw. Bleecker & to Carmine Streets 2200 7 HENRY STREET 7 Precinct Comm. Council 1600 from Pike to Jefferson Streets to East B'dway/Madison/Rutgers St. 2200 9 Schoolyard across street 9th Pct. Comm. Council 1400 from Precinct to Note: 9th Precinct moved to: 2000 321 E. 5th Street betw. 1st & 2nd Avenues 10 FULTON HOUSES PARK 10th Pct. Comm. Council 1700 W. 16th Street to betw. 9th & 10th Avenues 2030 13 PETERSFIELD (behind the 13 Precinct Comm. Council 1700 high school) 2nd Avenue betw. to 20th & 21st Streets 2000 MT So. (SEE 17TH PCT.) 17 DAG HAMMERSKJOLD PLZ. 17 Precinct Comm. Council 1600 PARK to East 47th St., betw. 1st & 2100 2nd Aves. MTN HELL'S KITCHEN PARK Mid-Town No. Precinct 1700 10th Avenue betw. Comm. Council to W. 47th & W. 48th Streets 2000 19 East 77th Street & Lexington 19 Pct. Comm.Council 1700 Avenue to 1900 20 VERDI SQUARE PARK 20 Pct. Comm. Council. 1800 W. 72nd to W.73rd Streets to betw. Broadway & Amsterdam 2000 Ave. CPP Maine Monument (Columbus Central Park Precinct 1600 Circle) inside of Centr. Park Community Council to at 60th Street & Centr.Pk.W. NY Road Runners Club 2000 23 East 114th Street betw. 23 & 25 Precinct Comm. 1700 East 116th & Pleasant Avenue Councils to 2100 PATROL BOROUGH MANHATTAN NORTH PCT. -

Barrymore Laurence Scherer on the Verdi Square Festival of the Arts - W

Barrymore Laurence Scherer on the Verdi Square Festival of the Arts - W... http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203440104574400723... Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF format. Order a reprint of this article now MUSIC SEPTEMBER 9, 2009, 11:43 P.M. ET By BARRYMORE LAURENCE SCHERER New York London may be famous for its squares—think Trafalgar, Berkeley, Leicester and Soho—but New York is no slouch in that department. Times Square is the traditional center of town. Duffy Square lies just to its north; Herald Square and Greeley Square lie roughly a half mile to the south. And all of these squares, and several of the city's others, share a common idiosyncrasy—they're actually triangular. They owe their shape to the intersection of various streets with Broadway, which cuts a diagonal swath through Manhattan. Verdi Square is the most beautiful such triangle. Formed where Broadway crosses Amsterdam Avenue at West 72nd Street, this small greenspace is named for Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901), the beloved Italian opera composer whose marble statue—supported by carved figures of four of his most memorable operatic characters—stands in frock-coated dignity amid the hubbub of the passing throng. Verdi's statue was unveiled on Columbus Day 1906, the work of the Sicilian Romantic sculptor Pasquale Civiletti. At the time of the unveiling, the nearby Hotel Ansonia was among the city's most elegant addresses, an exuberant example of Beaux Arts style and sometime home to the likes of Enrico Caruso, Arturo Toscanini and Theodore Dreiser. -

Italian Historical Society of Americanewsletter

Italian Historical Society of America Newsletter AUGUST 2015 BY JANICE THERESE MANCUSO VOLUME 11, NUMBER 8 Tutto Italiano Benvenuto a Tutto Italiano Aida, Don Carlo, Falstaff, La Traviata, Macbeth, Nabucco, Ortello, Rigoletto – some of the most popular operas in the world today – written, along with at least 20 others, by Giuseppe Verdi. Born in 1813 in the small village of Le Roncole (region of Emilia- Romagna), Verdi showed musical talent at a young age. When his family moved to the nearby town of Busseto, he gained support from the music director of the church and later, Antonio Barezzi, a local businessman. In 1932, Verdi applied to the Conservatorio di Milano but was rejected, with one reason being he was too old. (The school of music is now named Conservatorio G. Verdi di Milano.) With funding from Barezzi, Verdi stayed in Milan for three years, studying and attending performances at La Scala. Upon his return to Busseto, Verdi took the position of music director and married his childhood sweetheart, Margherita Barezzi, the daughter of his benefactor. He stayed in Busseto for three years, and then, with a desire to seek a career as a composer of opera, moved back to Milan, taking his wife and two children with him. His first opera, Oberto, opened at La Scala with great success; and he was contracted to compose three more works. His second opera was not well received; Verdi had lost his children and wife to illnesses and it greatly affected his work. He was persuaded to write a third opera, and Nabucco premiered in 1842 to rave reviews. -

Guide to the Postcard File Ca 1890-Present (Bulk 1900-1940) PR54

Guide to the Postcard File ca 1890-present (Bulk 1900-1940) PR54 The New-York Historical Society 170 Central Park West New York, NY 10024 Descriptive Summary Title: Postcard File Dates: ca 1890-present (bulk 1900-1940) Abstract: The Postcard File contains approximately 61,400 postcards depicting geographic views (New York City and elsewhere), buildings, historical scenes, modes of transportation, holiday greeting and other subjects. Quantity: 52.6 linear feet (97 boxes) Call Phrase: PR 54 Note: This is a PDF version of a legacy finding aid that has not been updated recently and is provided “as is.” It is key-word searchable and can be used to identify and request materials through our online request system (AEON). 2 The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections PR 054 POSTCARD FILE ca. 1890-present (bulk dates: 1900-1940) 52.6 lin. ft., 97 boxes Series I. Geographic Locations: United States Series II. Geographic Locations: International Series III. Subjects Processed by Jennifer Lewis January 2002 PR 054 3 Provenance The Postcard File contains cards from a variety of sources. Larger contributions include 3,340 postcard views of New York City donated by Samuel V. Hoffman in 1941 and approximately 10,000 postcards obtained from the stock file of the Brooklyn-based Albertype Company in 1953. Access The collection open to qualified researchers. Portions of the collection that have been photocopied or microfilmed will be brought to the researcher in that format; microfilm can be made available through Interlibrary Loan. Photocopying Photocopying will be undertaken by staff only, and is limited to twenty exposures of stable, unbound material per day. -

Fiscal Year 2019 Annual Report on Park Maintenance

Annual Report on Park Maintenance Fiscal Year 2019 City of New York Parks & Recreation Bill de Blasio, Mayor Mitchell J. Silver, FAICP, Commissioner Annual Report on Park Maintenance Fiscal Year 2019 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 Understanding Park Maintenance Needs ............................................................................... 1 How Parks are Maintained ...................................................................................................... 2 About the Data Used in this Report ....................................................................................... 3 Data Caveats .......................................................................................................................... 5 Report Column Definitions and Calculations ........................................................................... 5 Tables ...................................................................................................................................... Table 1 – Park-Level Services ............................................................................................ 8 Table 2 – Sector-Level Services ........................................................................................98 Table 3 – Borough and Citywide Work Orders ...................................................................99 Table 4 – Borough and Citywide-Level Services Not Captured in Work