The Crack in the Consensus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mamas and the Papas – California Dreamin' “If You're Going

The Mamas and the Papas – California dreamin’ “If you’re going to San Francisco be sure to wear some flowers in your hair” (John Phillips) 1.Els autors Influenciat per la “Generació Beat”, a mitjan anys 60 té lloc a San Francisco l’eclosió del moviment hippy. En la seva vessant musical, aquest nou moviment apostava decididament per una línia contestatària i subversiva, tant musicalment com en el contingut dels textos de les cançons, ara carregats de missatge. A partir d’aquest moment, la música passa a ser el mitjà d’expressió de la joventut, de la seva angoixa i del seu desig d’un altre món més lliure i just. I també de la crida per la pau, just en un moment de gran rebuig a la guerra del Vietnam. Els hippys predicaven l’evasió, la fugida (també a través de les drogues) d’un món i d’una societat incomprensibles. Els seus profetes literaris van ser Kerouac i Ginsberg. I entre els musics més significatius que van transmetre aquest missatge trobem The Mamas and the Papas. The Mamas and the Papas va ser una de les principals formacions de folk-pop sorgides a mitjan anys 60. Conjuntament amb altres grups, com ara Byrds, Beach Boys o Turtles, van omplir les llistes d’èxits de l’època amb cançons carregades de cors harmònics. El segell identificatiu del grup va ser la barreja de veus masculines (John Phillips i Denny Doherty) i femenines (Michelle Phillips i Cass Elliott) i la combinació de lletres sòlides amb arranjaments dels millors músics californians del moment. -

Sparrow Records Discography

Sparrow Discography by Mike Callahan, David Edwards & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Sparrow Records Discography Sparrow is a Contemporary Christian label founded in 1976 by Billy Ray Hearn. Hearn was the A&R Director for Word Records’ Myrrh label, founded a few years earlier also as a Contemporary Christian label. Sparrow also released records under their Birdwing subsidiary. Hearn’s Sparrow label was in competition with Hearn’s old boss, Word Records, and was quite successful. Even today, Sparrow is among the top Christian labels. Hearn sold the label to EMI in 1992, and it was placed under the Capitol Christian Music Group. Sparrow signed a distribution agreement with MCA in April, 1981 to release their product in the secular market while the regular Sparrow issues were distributed to Christian stores and Christian radio stations. The arrangement with MCA lasted until October, 1986, when Sparrow switched distribution to Capitol. Sparrow SPR-1001 Main Series: SPR-1001 - Through a Child’s Eyes - Annie Herring [1976] Learn A Curtsey/Where Is The Time/Wild Child/Death After Life/Grinding Stone/Hand On Me//Dance With You/Love Drops/Days Like These/First Love/Some Days/Liberty Bird/Fly Away Burden SPR-1002 - SPR-1003 - John Michael Talbot - John Michael Talbot [1976] He Is Risen/Jerusalem/How Long/Would You Crucify Him//Woman/Greewood Suite/Hallelu SPR-1004 - Firewind - Various Artists [1976] Artists include Anne Herring, Barry McGuire, John Talbot, Keith Green, Matthew Ward, Nelly Ward, and Terry Talbot (In other words, Barry McGuire, The Talbot Brothers, Keith Green, and The 2nd Chapter of Acts). -

Contemporary Christian Music History - 1965

Contemporary Christian Music History - 1965 If you were around in 1965, what was the Lord doing in your life? In 1965 the first American combat troops are sent to South Vietnam. A Russian cosmonaut became the first person to walk in space. Civil rights activists led by Martin Luther King began their march from Selma to the capitol in Montgomery. U.S. President Lynden B. Johnson signed the Social Security Act of 1965 into law establishing Medicare and Medicaid. In October of that year, in St. Louis, Missouri, the 630 foot tall parabolic steel gateway arch was completed. Sony introduced “Betamax”, a home video tape recorder. CBS switched to the “color standard”. 1965 in music saw The Beatles getting a lot of attention. The wedding of Beatle, Ringo Starr to Maureen Cox took place, The Beatles played Shea Stadium which was the first rock concert to be held in a venue of that size. Over fifty-five thousand attended and the movie “Help” starring The Beatles was released. The Beach Boys appeared on “Shindig!”. The Grateful Dead, The Byrds and Jefferson Airplane all started their careers in 1965. And in contemporary Christian music…Jesus music was beginning to have a noticeable effect on Christian music and getting noticed by the Church. Keith Green signed a 5-year general market contract with Decca Records in 1965 and was expected to be the next teen idol. He was twelve at the time and he did become the youngest member of ASCAP. By 1965 the Imperials had been singing together for about a year. -

1 Bob Dylan's American Journey, 1956-1966 September 29, 2006, Through January 6, 2007 Exhibition Labels Exhibit Introductory P

Bob Dylan’s American Journey, 1956-1966 September 29, 2006, through January 6, 2007 Exhibition Labels Exhibit Introductory Panel I Think I’ll Call It America Born into changing times, Bob Dylan shaped history in song. “Life’s a voyage that’s homeward bound.” So wrote Herman Melville, author of the great tall tale Moby Dick and one of the American mythmakers whose legacy Bob Dylan furthers. Like other great artists this democracy has produced, Dylan has come to represent the very historical moment that formed him. Though he calls himself a humble song and dance man, Dylan has done more to define American creative expression than anyone else in the past half-century, forming a new poetics from his emblematic journey. A small town boy with a wandering soul, Dylan was born into a post-war landscape of possibility and dread, a culture ripe for a new mythology. Learning his craft, he traveled a road that connected the civil rights movement to the 1960s counterculture and the revival of American folk music to the creation of the iconic rock star. His songs reflected these developments and, resonating, also affected change. Bob Dylan, 1962 Photo courtesy of John Cohen Section 1: Hibbing Red Iron Town Bobby Zimmerman was a typical 1950’s kid, growing up on Elvis and television. Northern Minnesota seems an unlikely place to produce an icon of popular music—it’s leagues away from music birthplaces like Memphis and New Orleans, and seems as cold and characterless as the South seems mysterious. Yet growing up in the small town of Hibbing, Bob Dylan discovered his musical heritage through radio stations transmitting blues and country from all over, and formed his own bands to practice the newfound religion of rock ‘n’ roll. -

FROM “WE SHALL OVERCOME” to “FORTUNATE SON”: the EVOLVING SOUND of PROTEST an Analysis on the Changing Nature of American Protest Music During the Sixties

FROM “WE SHALL OVERCOME” TO “FORTUNATE SON”: THE EVOLVING SOUND OF PROTEST An analysis on the changing nature of American protest music during the Sixties FLORIS VAN DER LAAN S1029781 MA North American Studies Supervisor: Frank Mehring 20 Augustus 2020 Thesis k Floris van der Laan - 2 Abstract Drawing on Denisoff’s theoretical framework - based on his analysis of the magnetic and rhetorical songs of persuasion - this thesis will examine how American protest music evolved during the Sixties (1960-1969). Songs of protest in relation to the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War gave a sound to the sociopolitical zeitgeist, critically addressing matters that were present throughout this decade. From the gentle sounds of folk to the dazzling melodies of rock, protest music became an essential cultural medium that inspired forms of collective thought. Ideas of critique and feelings of dissent were uniquely captured in protest songs, creating this intrinsic correlation between politics, music, and protest. Still, a clear changing nature can be identified whilst scrutinizing the musical phases and genres – specifically folk and rock - the Sixties went through. By taking a closer look on the cultural artifacts of protest songs, this work will try to demonstrate how American songs of protest developed during this decade, often affected by sociopolitical factors. From Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” to The Doors’ “The Unknown Soldier”, and from “Eve of Destruction” by Barry McGuire to “Superbird” by Country Joe and The Fish, a thorough analysis of protest music will be provided. On the basis of lyrics, melodies, and live performances, this thesis will discuss how protest songs reflected the mood of the times, and provided an ever-evolving destabilizing force that continuously adjusted to its social and political surroundings. -

Pop Goes to War, 2001–2004:U.S. Popular Music After 9/11

1 POP GOES TO WAR, 2001–2004: U.S. POpuLAR MUSIC AFTER 9/11 Reebee Garofalo Mainstream popular music in the United States has always provided a window on national politics. The middle-of-the-road sensibilities of Tin Pan Alley told us as much about societal values in the early twentieth century as rock and roll’s spirit of rebellion did in the fifties and sixties. To cite but one prominent example, as the war in Vietnam escalated in the mid-sixties, popular music provided something of a national referendum on our involvement. In 1965 and 1966, while the nation was sorely divided on the issue, both the antiwar “Eve of Destruction” by Barry McGuire and the military ode “The Ballad of the Green Berets” by Barry Sadler hit number one within months of each other. As the war dragged on through the Nixon years and military victory seemed more and more remote, however, public opinion began to turn against the war, and popular music became more and more clearly identified with the antiwar movement. Popular music—and in particular, rock—has nonetheless served con- tradictory functions in American history. While popular music fueled opposition to the Vietnam War at home, alienated, homesick GIs eased the passage of time by blaring those same sounds on the battlefield (as films such as Apocalypse Now and Good Morning, Vietnam accurately document). Rock thus was not only the soundtrack of domestic opposition to the war; it was the soundtrack of the war itself. This phenomenon was not wasted on military strategists, who soon began routinely incorporat- ing music into U.S. -

The Counterculture Movement

The Counterculture Era: Five Protest Songs (1965-70) The Counterculture Movement was an unorganized and varied attack by young people (called “beatniks” and “hippies”) against “the Establishment.” The conformity, materialism, and patriotism which typified the 1950s met head-on with “do your own thing” and “don’t trust anyone over 30.” It was a true clash of American eras—perhaps unequaled in United States history—and the immediate result was utter chaos. In the long term, hippies made important history by accident. Hippies unabashedly challenged traditional American cultural values, including attitudes toward sexual experience, experimentation with mind-altering drugs, and rejection of consumerism and compliance (manifested by communal living, long hair, shabby clothing, and loose speech). America’s youth were disgusted by slick disingenuous politicians, tired of idle political rhetoric, appalled by American racism, sickened by the brutality of Vietnam, leery of possible Cold War repercussions, and contemptuous of social smugness. Kids were at odds with the older generation about what exactly the “American dream” was and how to achieve it. The result was a marked “generation gap” filled with misunderstanding, intolerance, impatience, and distrust. The chief vehicle for the Counterculture assault on the Establishment was music, the most wholesome part of the hippies’ triadic credo of “sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll.” Indeed, the 1969 Woodstock Concert (officially “Woodstock Music & Art Fair”) has been referred to as the “Counterculture National Convention.” The following five selections, classic Counterculture Era music, are among those recognized foremost in the 1960s protest songs genre. “Eve of Destruction” by Barry McGuire [Words and music by P. -

The History of Protest Music Class 1: Origins and the Folk Revival Jim Dunphy [email protected]

The History of Protest Music Class 1: Origins and the Folk Revival Jim Dunphy [email protected] 1 What is a protest song? • Webster defines protest as: “a complaint, objection, or display of unwillingness usually to an idea or a course of action.” • For the purposes of this course, then, a protest song is a song AGAINST a government policy, not IN SUPPORT OF a government policy 2 So • “We Shall Overcome” is a protest song • “Ohio” is a protest song • “Imagine” is a protest song 3 But • “The Ballad of the Green Berets” is NOT a protest song • “Okie from Muscogee” is NOT a protest song 4 Also • This is a class on history and music • This is not the place to relitigate whether the protests or the protestors were right or wrong 5 But….. 6 If you want to buy the instructor a beer and do that, let the instructor know. 7 Finally A quote from the course description: The language in the songs is angry and at some times profane, and the images shown are disturbing. But they represent the true feelings of the artist in the moment, and what led to these feelings 8 So… You have been warned! 9 Billie Holiday April 7, 1915 – July 17, 1959 10 Billie Holiday • Born in Philadelphia in 1915, father left to join a jazz band • Mother worked odd jobs before moving to NY where she became a prostitute in a brothel, and Billie joined her in that profession at age 14 • She started singing after her release from prison, and signed her first recording contract at age 18. -

Bargainin' for Salvation : Bob Dylan, a Zen Master?

BARGAININ' FOR SALVATION Bargainin' For Salvation Bargainin' For Salvation Bob Dylan, A Zen Master? Steven Heine continuum NEW YORK • LONDON 2009 The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc 80 Maiden Lane, New York, NY 10038 The Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd The Tower Building, 1 1 York Road, London SEl 7NX www.continuumbooks.com Copyright © 2009 by Steven Heine All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Heine, Steven, 1950- Bargainin for salvation : Bob Dylan, a Zen master? / Steven Heine, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN- 13: 978-0-8264-2950-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN- 10: 0-8264-2950-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Dylan, Bob, 1941- Songs. Texts. 2. Dylan, Bob, 1941 —Criticism and interpretation. 3. Rock musicians-United States-Biography. 4. Creation (Literary, artistic, etc.)- Religious aspects-Zen Buddhism. I. Title. II. Title: Bob Dylan, a Zen master? ML420.D98H45 2009 782.42 164092-dc22 2009009919 Typeset by Newgen Imaging Systems Pvt Ltd, Chennai, India Printed in the United States of America Contents Acknowledgments vii List of Illustrations ix Preface: Satori in Amsterdam— I'll Let You Be in My Dreams If I Can Be in Yours xi 1. Dylan's Zen Rock Garden: Leaving His Heart in That Kyoto Temple 1 PARTI. ZEN AND DYLAN 2. A Simple Twist of Faith: Dylan's Enigmatic Spiritual Quest 27 3. From Beat Blues to Zen: Exploring the Roots of Dylan's Spirituality 44 4. -

MITCH MILLER SONGS: Disc One • Head of A&R for Columbia for Over 15 Years, TV Star, the DEFINITIVE COLLECTION 1

THE NEW CHRISTY MINSTRELS Ramblin’ featuring “Green, Green” SELLING POINTS: Expanded Edition • Along with The Kingston Trio, The New Christy Minstrels Were the Most Popular Group of the STREET DATE: August 5, 2016 Early ‘60s Folk Boom • 1963’s Ramblin’ Album Was Their Creative High Hey, folk music fans! Have we got a Real Gone treat for Water Mark, and Stayed on the Charts for you! The New Christy Minstrels’ classic Ramblin’ album 77 Weeks has long been considered that great group’s creative high water work. Released in July of 1963, the album instantly made • Expanded Edition Features the Hit “Green, Green” the charts and stayed there for 77 weeks, earning founder Randy Sparks and his in Unreleased and Foreign-Language Versions group their first Gold Record…and bringing fame and a little “Green, Green” to one • 13 Bonus Tracks in All Including Six Unreleased Barry McGuire. Here it is again, in long-overdue, sonically superior remastered form Songs: Highlighted by a Demo of “Last Farewell" – and now in an expanded edition loaded with rare material (including six unreleased tracks) related to the album! 1. Ramblin’ • Newly Remastered in Vastly Improved Sound by 2. Mighty Mississippi You’ll hear the creation of “Green, Green” – the group’s biggest hit – in unreleased 3. Hi Jolly Sean Brennan at Battery Studios in NYC versions that feature members Dolan Ellis, Jackie Miller, and Gayle Caldwell (later 4. A Travelin’ Man 5. Down the Ohio • Liner Notes by New Christy Minstrels Expert “Jackie and Gayle” of Shindig fame), with Barry McGuire on only the third verse. -

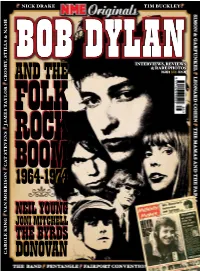

NME Dylan/Folk Rock Issue 2003

NICK DRAKE TIM BUCKLEY BOB DYLANBOB DYLAN INTERVIEWS, REVIEWS & RARE PHOTOS AND THE VOLUME 2 ISSUE 5 UK £ 5.99 & NASH STILLS CROSBY, FOLK ROCK BOOM 1964-1974 NEIL YOUNG JONI MITCHELL THE BYRDS CAROLE KING CAROLE MORRISON VAN STEVENS CAT DONOVAN TAYLOR JAMES DVD - EREDV519 Features the classic tracks 99.9F ˚, Marlene On The Wall, When Heroes Go Down, Left Of Center, Luka, Solitude Standing, Tom's Diner and many more. 2004 Includes bonus tracks from her concert DISTRIBUTED BY at the Montreux Festival in 2000. AVAILABLE AT eagle vision A DIVISION OF EAGLE ROCK ENTERTAINMENT LIMITED www.eagle-rock.com “FESTIVAL!” MURRAY LERNER’S CLASSIC FILM, originally released in 1967, is now on DVD for the first time. Filmed across four Newport Folk Festivals in the early sixties it combines live footage and interviews with the artists and with members of the audience. FEATURED ARTISTS INCLUDE BOB DYLAN • JOAN BAEZ • DONOVAN, PETER,PAUL & MARY • JOHNNY CASH, JUDY COLLINS and many more. EREDV499 DISTRIBUTED BY AVAILABLE FROM eagle vision A DIVISION OF EAGLE ROCK ENTERTAINMENT LTD www.eagle-rock.com Britain catches Dylanmania, Donovan versus Dylan, The Byrds fly in, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott reminisces, the great Protest Song debate, Barry McGuire heralds the ‘Eve Of Destruction’, Sonny & Cher conquer the charts, Simon & PAGES 6-39 Garfunkel forge sound out of silence Byrds banned in drug scandal, Dylan press deceptions and gig fracas, Simon & Garfunkel go “intellectual”, The Mamas And The Papas entertain The Beatles, Cat Stevens in “youth’s a drag” shocker, -

Sharing the Playlists of Our Lives…

Sharing the Playlists of our lives… Barry Guryan My favorite music has not changed since my years at Penn. We all had the unique treat of experiencing the sounds and cultural impact of both the Beatles and all the artists of Soul music while in their prime. I still remember seeing The Four Tops and The Temptations perform in person at Skimmer Weekend. I was also lucky enough to be in the audience at The Ed Sullivan Show on the night that Paul McCartney introduced “Yesterday”. Our music, like the events of our time-- truly historic in every way. Larry Miller Here is my playlist, it's heavily weighted to oldies and a little weird now that I look at it. 1. Gary US bonds: Quarter to 3 2. Smokey Robinson and the Miracles; Tracks of My Tears 3. Rolling Stones: Satisfaction, Honkey-tonk Women, Play with Fire, Sympathy for the Devil 4. Beatles: Norwegian Wood, When I'm 64(74) 5. Troggs; Wild Thing 6. Wild Cherry: Play That Funky Music 7. Elton John:: Philadelphia Freedom, Tiny Dancer 8. BeeGees: Staying Alive, Night Fever 9. Eric Clapton and Cream: Sunshine of Your Love. Layla 10. Fleetwood Mac::Go your own way 11. Donna Summer: I Will Always Love You 12. Creedence Clearwater: Up Around the Bend, Senator's Son 13. Ode to Joy 14. Righteous Brothers: You've Lost That Loving Feeling 15. Eagles: Life in the Fast Lane, Hotel California 16. Spencer Davis Group: Gimme Some Lovin 17. Doors Light My Fire 18. Doobie Brothers: Listen to the Music, What a Fool Believes 19.