The Yellow Nib 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art Collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956)

099-105dnh 10 Clark Watson collection_baj gs 28/09/2015 15:10 Page 101 The BRITISH ART Journal Volume XVI, No. 2 The art collection of Peter Watson (1908–1956) Adrian Clark 9 The co-author of a ously been assembled. Generally speaking, he only collected new the work of non-British artists until the War, when circum- biography of Peter stances forced him to live in London for a prolonged period and Watson identifies the he became familiar with the contemporary British art world. works of art in his collection: Adrian The Russian émigré artist Pavel Tchelitchev was one of the Clark and Jeremy first artists whose works Watson began to collect, buying a Dronfield, Peter picture by him at an exhibition in London as early as July Watson, Queer Saint. 193210 (when Watson was twenty-three).11 Then in February The cultured life of and March 1933 Watson bought pictures by him from Tooth’s Peter Watson who 12 shook 20th-century in London. Having lived in Paris for considerable periods in art and shocked high the second half of the 1930s and got to know the contempo- society, John Blake rary French art scene, Watson left Paris for London at the start Publishing Ltd, of the War and subsequently dispatched to America for safe- pp415, £25 13 ISBN 978-1784186005 keeping Picasso’s La Femme Lisant of 1934. The picture came under the control of his boyfriend Denham Fouts.14 eter Watson According to Isherwood’s thinly veiled fictional account,15 (1908–1956) Fouts sold the picture to someone he met at a party for was of consid- P $9,500.16 Watson took with him few, if any, pictures from Paris erable cultural to London and he left a Romanian friend, Sherban Sidery, to significance in the look after his empty flat at 44 rue du Bac in the VIIe mid-20th-century art arrondissement. -

Cecil Beaton: VALOUR in the FACE of BEAUTY

Cecil Beaton: VALOUR IN THE FACE OF BEAUTY FROM BRIGHT YOUNG THING AND DOCUMENTER OF LONDON‘S LOST GENERATION OF THE 20S TO A DOCUMENTER OF A NEW GENERATION WHO WOULD LOSE THEIR LIVES IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR, THIS IS JUST ONE SLICE OF Cecil Beaton‘s REMARKABLE LIFE THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHY. ©THE CECIL BEATON STUDIO ARCHIVE AT SOTHEBY’S. STUDIO ARCHIVE AT ©THE CECIL BEATON TEXT Mark Simpson CECIL BEATON SELF-PORTRAIT, CAMBRIDGE FOOTLIGHTS, 1925 Another Another 254 Man Summer/Autumn 2020 Man 255 CECIL BEATON In a world saturated with social me-dear surveillance and Beaton: No, no one could help me. It was up to me to find suffused with surplus selfies, being ‘interesting’ becomes ever- the sort of world that I wanted. more compulsory – just as it becomes ever-more elusive. Not Face to Face, 1962 just for artists in this brave new connected, visual, attention- seeking world, but for civilians too. Cecil Walter Hardy Beaton was born in 1904 into a Little wonder that Cecil Beaton, a man who essentially prosperous Edwardian middle-class family in Hampstead, a invented himself and his astonishing career with a portable leafy suburb of London. He was the product of true theatrical camera loaded with his ambition and longing, one of the romance: his mother Esther was a Cumbrian blacksmith’s brightest of his bright young generation of the 1920s, has daughter who was visiting London when she fell in love with become more famous, not less. As we plough relentlessly into his father Ernest, a timber merchant, after seeing him onstage a 21st century that he anticipated in many ways, long before in the lead role in an amateur dramatic production. -

Life Is a Dream

Paul Durcan Life is a Dream 40 Years Reading Poems 1967-2007 Harvill Seeker LONDON Contents Foreword xix Acknowledgements xx ENDSVILLE (1967) The White Window 3 O WESTPORT IN THE LIGHT OF ASIA MINOR (1975) Nessa 7 Gate 8 8 On a BEA Trident Jet 9 Hymn to Nessa 9 Le Bal 10 O Westport in the Light of Asia Minor 10 Phoenix Park Vespers 12 In the Springtime of Her Life My Love Cut Off Her Hair 13 The Daughters Singing to Their Father 14 The Nun's Bath 14 Combe Florey 15 Please Stay in the Family, Clovis 15 Black Sister 16 November 30, 1967 17 They Say the Butterfly is the Hardest Stroke 17 La Terre des Hommes 18 Aughawall Graveyard 18 Ireland 1972 18 The Girl with the Keys to Pearse's Cottage 18 Dun Chaoin 19 The Day of the Starter 20 The Limerickman that Went to the Bad 20 The Night They Murdered Boyle Somerville 21 Tribute to a Reporter in Belfast, 1974 22 Letter to Ben, 1972 23 vii TERESA'S BAR (1976) The Difficulty that is Marriage 27 She Mends an Ancient Wireless 27 Two in a Boat 28 Anna Swanton 28 Wife Who Smashed Television Gets Jail 29 Teresa's Bar 3O Polycarp 32 Lord Mayo 33 The Drover's Path Murder 34 Before the Celtic Yoke 35 What is a Protestant, Daddy? 36 The Weeping Headstones of the Isaac Becketts 37 In Memory of Those Murdered in the Dublin Massacre, May 1974 38 Mr Newspapers 39 The Baker 40 The Archbishop Dreams of the Harlot of Rathkeale 40 The Friary Golf Club 41 The Hat Factory 42 The Crown of Widowhood 45 Protestant Old Folks' Coach Tour of the Ring of Kerry 45 Goodbye Tipperary 46 The Kilfenora Teaboy 47 SAM'S CROSS (1978) -

Fall 2003 Archipelago

archipelago An International Journal of Literature, the Arts, and Opinion www.archipelago.org Vol. 7, No. 3 Fall 2003 AN LEABHAR MÒR / THE GREAT BOOK OF GAELIC An Exhibiton : Twenty-two Irish and Scottish Gaelic Poems, Translations and Artworks, with Essays and Recitations Fiction: PATRICIA SARRAFIAN WARD “Alaine played soccer with the refugees, she traded bullets and shrapnel around the neighborhood . .” from THE BULLET COLLECTION Poem: ELEANOR ROSS TAYLOR Our Lives Are Rounded With A Sleep Reflection: ANANT KUMAR The Mosques on the Banks of the Ganges: Apart or Together? tr. from the German by Rajendra Prasad Jain Photojournalism: PETER TURNLEY Seeing Another War in Iraq in 2003 and The Unseen Gulf War : Photographs Audio report on-line by Peter Turnley Endnotes: KATHERINE McNAMARA The Only God Is the God of War : On BLOOD MERIDIAN, an American myth printed from our pdf edition archipelago www.archipelago.org CONTENTS AN LEABHAR MÒR / THE GREAT BOOK OF GAELIC 4 Introduction : Malcolm Maclean 5 On Contemporary Irish Poetry : Theo Dorgan 9 Is Scith Mo Chrob Ón Scríbainn ‘My hand is weary with writing’ 13 Claochló / Transfigured 15 Bean Dubh a’ Caoidh a Fir Chaidh a Mharbhadh / A Black Woman Mourns Her Husband Killed by the Police 17 M’anam do sgar riomsa a-raoir / On the Death of His Wife 21 Bean Torrach, fa Tuar Broide / A Child Born in Prison 25 An Tuagh / The Axe 30 Dan do Scátach / A Poem to Scátach 34 Èistibh a Luchd An Tighe-Se / Listen People Of This House 38 Maireann an t-Seanmhuintir / The Old Live On 40 Na thàinig anns a’ churach -

Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Senior Scholar Papers Student Research 1998 From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition Rebecca Troeger Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Troeger, Rebecca, "From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition" (1998). Senior Scholar Papers. Paper 548. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars/548 This Senior Scholars Paper (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Scholar Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Rebecca Troeger From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition • The Irish literary tradition has always been inextricably bound with the idea of image-making. Because of ueland's historical status as a colony, and of Irish people's status as dispossessed of their land, it has been a crucial necessity for Irish writers to establish a sense of unique national identity. Since the nationalist movement that lead to the formation of the Insh Free State in 1922 and the concurrent Celtic Literary Re\'ivaJ, in which writers like Yeats, O'Casey, and Synge shaped a nationalist consciousness based upon a mythology that was drawn only partially from actual historical documents, the image of Nation a. -

Universidad Autónoma Del Estado De México Facultad De Humanidades Licenciatura En Letras Latinoamericanas TESIS PARA OBTENER

Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México Facultad de Humanidades Licenciatura en Letras Latinoamericanas TESIS PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADA EN LETRAS LATINOAMERICANAS Hacia la fundación de Santa María. La composición lírico-narrativa de La vida breve de Juan Carlos Onetti María José Gallardo Rubio Asesor Mtro. David de la Torre Cruz Toluca, Estado de México Noviembre 2018 1 ÍNDICE Introducción 3 1. Juan Carlos Onetti, novelista de la modernidad literaria 10 1.1. La novela moderna latinoamericana 10 1.2. La novela existencialista del Cono Sur 18 1.3. El mito en torno a Onetti y La vida breve 23 2. La vida breve, una novela lírica 34 2.1. Lo lírico y lo narrativo 34 2.2. El lirismo y la imagen 40 2.3. El lirismo de La vida breve 61 3. El diseño poético: la escritura autoficcional 82 3.1. La vida breve, novela fundacional 82 3.2. Onetti y la máscara Brausen 86 4. El diseño poético: imágenes del yo 106 4.1. El autorretrato simbólico de Brausen 106 4.2. Brausen y sus máscaras: autoafirmación y camuflaje 111 4.2.1. Brausen y Gertrudis 114 4.2.2. Díaz Grey y Elena Sala 117 4.2.3. Juan María Arce y la Queca 123 5. El diseño poético: imágenes del mundo 129 5.1. El alter deus: padre de Santa María 129 5.2. La fundación de Santa María: la visión lírica 140 Conclusiones 148 Bibliografía 155 2 Introducción Tras leer algunas de las obras más representativas de Juan Carlos Onetti, El pozo (1939), La cara de la desgracia (1960), El astillero (1961), La muerte y la niña (1973) y por supuesto, La vida breve (1950), se advierte un rasgo concluyente de la poética del escritor, un tipo de escritura de gran contenido expresivo y emocional que revela una visualidad y plasticidad verbal insospechada. -

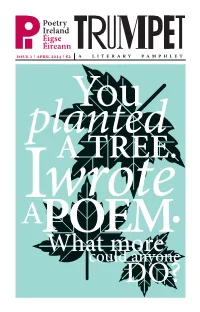

Issue 6 April 2017 a Literary Pamphlet €4

issue 6 april 2017 a literary pamphlet €4 —1— Denaturation Jean Bleakney from selected poems (templar poetry, 2016) INTO FLIGHTSPOETRY Taken on its own, the fickle doorbell has no particular score to settle (a reluctant clapper? an ill-at-ease dome?) were it not part of a whole syndrome: the stubborn gate; flaking paint; cotoneaster camouflaging the house-number. Which is not to say the occupant doesn’t have (to hand) lubricant, secateurs, paint-scraper, an up-to-date shade card known by heart. It’s all part of the same deferral that leaves hanging baskets vulnerable; although, according to a botanist, for most plants, short-term wilt is really a protective mechanism. But surely every biological system has its limits? There’s no going back for egg white once it’s hit the fat. Yet, some people seem determined to stretch, to redefine those limits. Why are they so inclined? —2— INTO FLIGHTSPOETRY Taken on its own, the fickle doorbell has no particular score to settle by Thomas McCarthy (a reluctant clapper? an ill-at-ease dome?) were it not part of a whole syndrome: the stubborn gate; flaking paint; cotoneaster Tara Bergin This is Yarrow camouflaging the house-number. carcanet press, 2013 Which is not to say the occupant doesn’t have (to hand) lubricant, secateurs, paint-scraper, an up-to-date Jane Clarke The River shade card known by heart. bloodaxe books, 2015 It’s all part of the same deferral that leaves hanging baskets vulnerable; Adam Crothers Several Deer although, according to a botanist, carcanet press, 2016 for most plants, short-term wilt is really a protective mechanism. -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

What More Could Anyone Do?

issue 1 / april 2014 / €2 a literary pamphlet You planted A TREE. Iwrote APOEM. Whatcould more anyone DO? My father, the least happy man I have known. His face retained the pallor The of those who work underground: the lost years in Brooklyn listening to a subway shudder the earth. Cage But a traditional Irishman who (released from his grille John Montague in the Clark Street IRT) drank neat whiskey until from new collected poems he reached the only element (the gallery press, 2012) he felt at home in any longer: brute oblivion. And yet picked himself up, most mornings, to march down the street extending his smile to all sides of the good, (all-white) neighbourhood belled by St Teresa's church. When he came back we walked together across fields of Garvaghey to see hawthorn on the summer hedges, as though he had never left; a bend in the road which still sheltered primroses. But we did not smile in the shared complicity of a dream, for when weary Odysseus returns Telemachus should leave. Often as I descend into subway or underground I see his bald head behind the bars of the small booth; the mark of an old car accident beating on his ghostly forehead. —2— 21 74 Sc ience and W onder by Richard Hayes Iggy McGovern A Mystic Dream of 4 quaternia press, €11.50 Iggy McGovern’s A Mystic Dream of 4 is an ambitious sonnet sequence based on the life of mathematician William Rowan Hamilton. Hamilton was one of the foremost scientists of his day, was appointed the Chair of Astronomy in Dublin University (Trinity College) while in the final year of his degree, and was knighted in 1835. -

The Great War in Irish Poetry

Durham E-Theses Creation from conict: The Great War in Irish poetry Brearton, Frances Elizabeth How to cite: Brearton, Frances Elizabeth (1998) Creation from conict: The Great War in Irish poetry, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5042/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Creation from Conflict: The Great War in Irish Poetry The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Frances Elizabeth Brearton Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D Department of English Studies University of Durham January 1998 12 HAY 1998 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the impact of the First World War on the imaginations of six poets - W.B. -

HEANEY, SEAMUS, 1939-2013. Seamus Heaney Papers, 1951-2004

HEANEY, SEAMUS, 1939-2013. Seamus Heaney papers, 1951-2004 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Heaney, Seamus, 1939-2013. Title: Seamus Heaney papers, 1951-2004 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 960 Extent: 49.5 linear feet (100 boxes), 3 oversized papers boxes (OP), and AV Masters: 1 linear foot (2 boxes) Abstract: Personal papers of Irish poet Seamus Heaney consisting mostly of correspondence, as well as some literary manuscripts, printed material, subject files, photographs, audiovisual material, and personal papers from 1951-2004. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on access Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses 'A forest of intertextuality' : the poetry of Derek Mahon Burton, Brian How to cite: Burton, Brian (2004) 'A forest of intertextuality' : the poetry of Derek Mahon, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1271/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "A Forest of Intertextuality": The Poetry of Derek Mahon Brian Burton A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted as a thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Durham Department of English Studies 2004 1 1 JAN 2u05 I Contents Contents I Declaration 111 Note on the Text IV List of Abbreviations V Introduction 1 1. 'Death and the Sun': Mahon and Camus 1.1 'Death and the Sun' 29 1.2 Silence and Ethics 43 1.3 'Preface to a Love Poem' 51 1.4 The Terminal Democracy 59 1.5 The Mediterranean 67 1.6 'As God is my Judge' 83 2.