Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symphonieorchester Des Bayerischen Rundfunks 16 17

16 17 SYMPHONIEORCHESTER DES BAYERISCHEN RUNDFUNKS Donnerstag 23.2.2017 Freitag 24.2.2017 3. Abo A Philharmonie 20.00 – ca. 22.00 Uhr Samstag 25.2.2017 3. Abo S Philharmonie 19.00 – ca. 21.00 Uhr 16 / 17 SIR JOHN ELIOT GARDINER Leitung SYMPHONIEORCHESTER DES BAYERISCHEN RUNDFUNKS KONZERTEINFÜHRUNG Do./Fr., 23./24.2.2017 18.45 Uhr Sa., 25.2.2017 17.45 Uhr Moderation: Antje Dörfner LIVE-ÜBERTRAGUNG IN SURROUND im Radioprogramm BR-KLASSIK Freitag, 24.2.2017 PausenZeichen: Robert Jungwirth im Gespräch mit Sir John Eliot Gardiner VIDEO-AUFZEICHNUNG ON DEMAND Das Konzert ist in Kürze auf br-klassik.de als Audio und Video abrufbar. PROGRAMM Emmanuel Chabrier Ouvertüre zur Opéra »Gwendoline« • Allegro con fuoco »Suite pastorale« für Orchester • Idylle. Andantino, poco con moto – Doux • Danse villageoise. Allegro risoluto • Sous bois. Andantino • Scherzo-Valse. Allegro vivo »Fête polonaise« aus der Opéra comique »Le Roi malgré lui« • Allegro molto animato »España«, Rhapsodie für Orchester • Allegro con fuoco Pause Claude Debussy »Images« für Orchester • Rondes de printemps. Modérément animé [Nr. 3] • Gigues. Modéré [Nr. 1] • Ibéria [Nr. 2] I. Par les rues et par les chemins. Assez animé II. Les parfums de la nuit. Lent et rêveur III. Le matin d’un jour de fête. Dans un rythme de Marche lointaine, alerte et joyeuse Wegweiser der französischen Moderne Orchesterwerke von Emmanuel Chabrier Matthias Corvin Uraufführungsdaten Ouvertüre zu Gwendoline : 10. April 1886 am Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brüssel; Suite pastorale : 4. November 1888 beim Musikfestival in Angers; Le Roi malgré lui : 18. Mai 1887 an der Pariser Opéra-Comique; España : 6. -

Emmanuel Chabrier Et Moi 79 Daniel Jacobson 27 a Conversation with Nicolas Le Riche

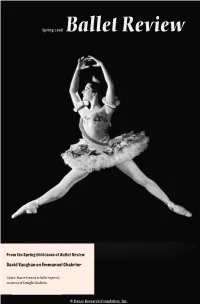

Spring 2008 Ball et Revi ew From the Spring 2008 issue of Ballet Review David Vaughan on Emmanuel Chabrier Cover: Marie-Jeanne in Ballet Imperial , courtesy of Dwight Godwin. © Dance Research Foundation, Inc. 4 Amsterdam – Clement Crisp 5 Chicago – Joseph Houseal 6 Toronto – Gary Smith 7 Oakland – Leigh Witchel 8 St. Petersburg, Etc. – Kevin Ng 10 Hamilton – Gary Smith 11 London – Joseph Houseal 13 San Francisco – Leigh Witchel 15 Toronto – Gary Smith David Vaughan 17 Emmanuel Chabrier et Moi 79 Daniel Jacobson 27 A Conversation with Nicolas Le Riche Joseph Houseal 39 Lucinda Childs: Counting Out the Bomb Photographs by Costas 43 Robbins Onstage Edited by Francis Mason 43 Nina Alovert Ballet Review 36.1 50 A Conversation with Spring 2008 Vladimir Kekhman Associate Editor and Designer: Joseph Houseal Marvin Hoshino 53 Tragedy and Transcendence Associate Editor: Don Daniels Davie Lerner 59 Marie-Jeanne Assistant Editor: Joel Lobenthal Marilyn Hunt 39 Photographers: 74 ABT: Autumn in New York Tom Brazil Costas Sandra Genter Subscriptions: 79 Next Wave XXV Roberta Hellman Copy Editor: Elizabeth Kattner Barbara Palfy 88 Marche Funèbre , A Lost Work Associates: of Balanchine Peter Anastos Robert Gres kovic 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris George Jackson 27 100 Check It Out Elizabeth Kendall Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Sutton David Vaughan Edward Willinger Sarah C. Woodcock Cover: Marie-Jeanne in Ballet Imperial , courtesy of Dwight Godwin. Emmanuel Chabrier he is thought by many to be the link between eighteenth-century French compos ers such et Moi as Rameau and Couperin, and later ones like Debussy and Ravel, both of whom revered his music, as did Erik Satie, Reynaldo Hahn, and David Vaughan Francis Poulenc (who wrote a book about him). -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 17, 1897

MUSIC HALL, BALTIMORE. Boston Symphony Orchestra. Mr. EMIL PAUR, Conductor. Seventeenth Season, 1897-98. PROGRAMME OF THE FIRST CONCERT WEDNESDAY EVENING, NOV. 10, 1897, AT 8.15 PRECISELY. With Historical and Descriptive Notes by William F. Apthorp. PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER. Steinway & Sons, Piano Manufacturers BY APPOINTMENT TO HIS MAJESTY, WILLIAM II., EMPEROR OF GERMANY. THE ROYAL COURT OF PRUSSIA. His Majesty, FRANCIS JOSEPH, Emperor of Austria. HER MAJESTY, THE QUEEN OF ENGLAND. Their Royal Highnesses, THE PRINCE AND PRINCESS OF WALES. THE DUKE OF EDINBURGH. His Majesty, UMBERTO I., the King of Italy. Her Majesty, THE QUEEN OF SPAIN. His Majesty, Emperor William II. of Germany, on June 13, 1893, also bestowed on our Mr. William Stbinway the order of Thb Rbd Eaglh, III Class, an honor never before granted to a manufacturer. The Royal Academy Of St. Ceecilia at Rome, Italy, founded by the celebrated composer Pales- trina in 1584, has elected Mr. William Steinway an honorary member of that institution. The following is the translation of his diploma : — The Royal Academy 0/ St. Ceecilia have, on account of his eminent merit in the domain of music, and in conformity to their Statutes, Article 12, solemnly decreed to receive William Stein- way into the number of their honorary members. Given at Rome, April 15, 1894, and in the three hundred and tenth year from the founding of the society. Alex Pansotti, Secretary. E. Di San Martino, President ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUES MAILED FREE ON APPLICATION STEINWAY & SONS, Warerooms, Steinway Hall, 107-111 East 14th St., New York, EUROPEAN DEPOTS : Steinway Hall, 15 and 17 Lower Seymour St., Portman Sq., W., London, England. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 17, 1897-1898

£.13! Jtefln&Ijamlm STYLE AA. Especial attention NEW SMALL and inspection GRAND. respectfully invited. The world-renowned house of Mason & Hamlin was founded in \ 854 as a firm. In 1868 the firm became a corporation, and is known as the Mason & Hamlin Company. From its inception its standard of manufacture has been the highest. Believing that there is always demand for the highest possible degree of excellence in a given manu- facture, the Mason & Hamlin Company has held steadfast to its origi- nal principle, and has never swerved from its purpose of producing instruments of rare artistic merit. As a result the Mason & Hamlin Company has received for its products, since its foundation to the present day, words of greatest commendation from the world's most illustrious musicians and critics of tone. Since and including the Great World's Exposition of Paris, 1867, the instruments manufactured by the Mason & Hamlin Company have received wherever exhibited, at all Great World's Expositions, the HIGHEST POSSIBLE AWARDS. New England Representative, MASON & HAMLIN BUILDING, 146 Boylston Street, BOSTON. Boston , Music Hall, Boston. Symphony s — A SEVENTEENTH SEASON, Orchestra i897-98 EMIL PAUR, Conductor. ;e»i«oo:i*ajvi:;m:e> OF THE Thirteenth Rehearsal and Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY WILLIAM F. APTHORP. Friday Afternoon, January 28, At 2.30 o'clock. Saturday Evening, January 29, At 8 o'clock. PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER. (385) Steinway & Sons, Piano Manufacturers BY APPOINTMENT TO HIS MAJESTY, WILLIAM II., EMPEROR OF GERMANY. THE ROYAL COURT OF PRUSSIA. His Majesty, FRANCIS JOSEPH, Emperor of Austria. -

An Examination of the German Influence on Thematic

An Examination of the German Influence on Thematic Development, Chromaticism and Instrumentation of Ernest Chausson's Concert for Piano, Violin and String Quartet, Op.21 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Chiang, Chen-Ju Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 13:38:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195479 AN EXAMINATION OF THE GERMAN INFLUENCE ON THEMATIC DEVELOPMENT, CHROMATICISM AND INSTRUMENTATION IN ERNEST CHAUSSON'S CONCERT FOR PIANO, VIOLIN AND STRING QUARTET, OP. 21 by Chen -Ju Chiang __________________ A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 6 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Chen -Ju Chiang entitled An Examination of the German Influence on Thematic Development, Chromaticism and Instrumentation in Ernest Chausson's Concert for Piano, Violin and Stri ng Quartet, Op. 21 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _____________________________________________________________________ Paula Fan Date: 4/14/06 _____________________________________________________________________ Tannis Gibson Date: 4/14/06 _____________________________________________________________________ Lisa Zdechlik Date: 4/14/06 Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate's submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

Opera Program 7-13 RBF Program 4-16 2

the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard college Emmanuel Chabrier’s The King in Spite of Himself July 27 – August 5, 2012 The Music Director, Musicians, and Staff of the American Symphony Orchestra dedicate these performances to the memory of Ronald Sell (1944–2012) Distinguished French horn player, member of the Orchestra for more than four decades, personnel manager, friend and colleague. His wisdom, grace, and humor will be missed. About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk-taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium-arch space, and in the 220-seat Theater Two, which fea- tures a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrates its 23rd year in August with “Saint-Saëns and His World.” The 2013 festival will be devoted to Igor Stravinsky, with a special weekend focusing on the works of Duke Ellington. The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, the former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the con- tributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. -

Rehearsal and Concert

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON 6- MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES », , . ( Ticket Office, 1492 ) „ , _ Telephones-, . , . ^. „_ _-_„ , Back Bay ^ Administration^ ' I Offices, 3200 \ TWENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1907-1908 DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor Prngramm? of tij? Eighteenth Rehearsal and Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON, MARCH 13 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, MARCH 14 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER 1346 : piANa Used and indorsed by Reisenauer, Neitzel, Burmeister, Gabrilowitsch, Nordica, Campanari, Bispham, and many other noted artists, will be used by TERESA CARRENO during her tour of the United States this season. The Everett piano has been played recently under the baton of the following famous conductors Theodore Thomas Franz Kneisel Dr. Karl Muck Fritz Scheel ^A^alter Damrosch Frank Damrosch Frederick Stock F. Van Der Stucken W^assily Safonoff Emil Oberhoffer Wilhelm Gericke Emil Paur Felix Weingartner REPRESENTED BY G. L SCHIRMER & COMPANY, 38 Huntington Avenue, Boston, Mass. 1346 Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL Twenty -seventh Season, 1907- 1908 n (tf^ic'ktvin^ I Miano Bears a name which has become known to purchasers as representing the highest possible value produced in the piano industry. It has been associated with all that is highest and best in piano making since 1823. Its name is the hall mark of piano worth and is a guarantee to the purchaser that in the instrument bearing it, is incorporated the highest artistic value possible. 1348 TWENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, NINETEEN HUNDRED SEVEN and EIGHT Eighteenth Rehearsal and Concert* FRIDAY AFTERNOON, MARCH 13, at 2.30. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 27,1907

MEMORIAL HALL . COLUMBUS Twenty-seventh Season, J907-J908 "^JT *% £% 9 fT f\ DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor •Programme of GRAND CONCERT WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE THURSDAY EVENING, JANUARY 30, AT 8.15 PRECISELY PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER " tgJRfY-EOlJRTH YEAR IJNfeST CONSERVATORY IN THE WEST Detroit Conservatory of Music FRANCIS L. YORK, M.A., Director One of the Three Largest Conservatories in America. Unsurpassed ad- vantages for a Complete Musical Education. EVERY BRANCH TAUGHT HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS: YORK, Piano; YUNCK, Violin; NORTON, Voice; RENWICK, Organ, Theory; DENNIS, Public School Music; OCKENDEN, Elocution ; LITTLE, Drawing. Fifty thoroughly reliable instructors. Rates of tuition range from $10 to $60 per term (twenty lessons). Many free advantages. Send for catalogue. 530 WOODWARD AVENUE JAMES H. BELL, Secretary EIGHTH PRINTING of " one of the most important books on music that have ever been published ... a style which can be fairly described as fascinating. — W. J. Henderson. With a chapter by Henry E. Krehbiel, covering Richard Strauss, Cornelius, Goldmark, Kienzl, Humperdinck, Smetana, Dvorak, Charpentier, Sullivan, Elgar, etc., in addition to his earlier chapter on Music in America. Practically a cyclopaedia of its subject, with 1,000 topics in the index LAVIGNAC'S " MUSIC AND MUSICIANS " By the Author of" The Music Dramas of Richard "Wagner " Translated by WILLIAM MARCHANT i2mo. $1.75 net (by mail $1.90). **# Circular with sample pages sent on application This remarkable book by the doyen of the Paris Conservatory has been accepted as a standard work in America and reprinted in England. It is difficult to give an idea of its comprehensiveness, with its 94 illustrations and 510 examples in Musical Notation. -

Emmanuel Chabrier an Annotated Bibliography

Emmanuel Chabrier An Annotated Bibliography Compiled by Weston Sims April 2020 Introduction Emmanuel Chabrier, the obscure yet notable composer, is a subject of common interest for musicologists. Efforts have been made by many to capture his musical essence and personality. Many resources were searched to obtain a general idea of what research has been done, and what areas are still in need of being addressed. Of the methodologies represented, historical research constitutes a large portion of the works listed. Comprehensive biographies, biographical articles, or articles focused on specific areas of Chabrier’s life are all present in the body of research. These biographies span a century of musicological scholarship. Among the most accomplished scholars on Chabrier is Roger Delage. Much of his life was spent researching and writing about Chabrier. Drawing upon letters, documents, and other sources, Delage examined Chabrier’s personality, musical style, and context. Various topics represented in the gathered sources are Chabrier’s songwriting, relationships with Impressionist painters, influences on future composers, and his travels to Spain. His 1999 capstone work Emmanuel Chabrier accounts for one of the most exhaustive biographies in musicological research on Chabrier. The various aspects of his life (childhood, family life, career, professional relationships, health, etc.) are well understood and represented in this research. Musical reception to his works is also well documented. While these biographies usually contain some kind of musical analysis, they typically seek to convey an understanding of their historical context, such as the influence of Impressionist artists on Chabrier’s music. However, that is beginning to shift as musicologists are recognizing the analysis that is left to be done. -

THE ARTIST and the ENTERTAINERS: EMMANUEL CHABRIER and HIS IMITATORS by MARY HELEN STILL (Under the Direction of Dorothea Link)

THE ARTIST AND THE ENTERTAINERS: EMMANUEL CHABRIER AND HIS IMITATORS by MARY HELEN STILL (Under the Direction of Dorothea Link) ABSTRACT Composed by Emmanuel Chabrier in 1877, the opera L’Étoile quickly become fodder for “borrowing” by American and British musical comedy collaborators. An American adaptation by Woolson Morse, The Merry Monarch, was produced in 1890, and a British adaptation by Ivan Caryll, The Lucky Star, was produced in London in 1899. Each subsequent version is in no way simply a translation or reproduction of L’Étoile; these are adaptations in a broad sense, with little Chabrier left at all. It is the purpose of this thesis to demonstrate by means of this case study how the musical comedy genre and the popular music industry of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries made use of an established and canonic genre, opera, by investigating what is appropriated and what is not valued in this borrowing process. INDEX WORDS: L’Étoile, The Merry Monarch, The Lucky Star, Emmanuel Chabrier, Eugène Leterrier, Albert Vanloo, H. Woolson Morse, J. Cheever Goodwin, Ivan Caryll, Charles H. Brookfield, Adrian Ross, Aubrey Hopwood THE ARTIST AND THE ENTERTAINERS: EMMANUEL CHABRIER AND HIS IMITATORS by MARY HELEN STILL BA, Piedmont College, 2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2013 © 2013 Mary Helen Still All Rights Reserved THE ARTIST AND THE ENTERTAINERS: EMMANUEL CHABRIER AND HIS IMITATORS by MARY HELEN STILL Major Professor: Dorothea Link Committee: David Haas Adrian Childs Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2013 iv DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my almost husband and best friend, Shakib Hoque, my sweet family, and my puppy, Henry, who never let me work too hard for too long. -

Chabrier Alexis Emanuel

CHABRIER ALEXIS EMANUEL Compositore francese (Albert, Alvernia, 18 I 1841 – Parigi 13 IX 1894) Figlio unico di una famiglia borghese, Chabrier si formò in un ambiente dove la tradizione degli studi di diritto e dell'impiego pubblico rappresentavano il punto d'onore, il certificato di appartenenza ad un ceto sociale. Nel 1851 gli Chabrier si trasferirono a Clermont-Fernand e nel 1856 a Parigi, dove Emanuel si laureò nel 1861 e fu assunto nello stesso anno al ministero dell'interno, con la qualifica di soprannumerario; fu quello il primo dei diciotto anni della sua carriera burocratica. Irregolari, di necessità, gli studi musicali. Ad Albert, Chabrier prese lezioni di pianoforte da M. Zaporta e da M. Pitarch, entrambi profughi Carlisti. A Clermont-Ferrand si affidò al violinista polacco Tarnowski. A questa prima infanzia risalgono numerosi pezzi pianistici dai titoli romanticamente descrittivi. Opere, secondo A. Cortot, "assolutamente povere e banali". A Parigi prese lezioni di pianoforte da un altro polacco, E. Wolff, compositore e virtuoso, condiscepolo, ed amico di Chopin. Si esercitò seriamente nella composizione, guidato da E. Semet e successivamente da A. Higuard, musicista di qualche fama, vincitore del Prix de Rome. Funzionario al ministero, Chabrier si inserì nei cenacoli della capitale. I compagni di gioventù erano piuttosto letterati e pittori che musicisti. Carattere gioviale, simpatico e bizzarro, come fa fede il suo epistolario condito di espressioni idiomatiche, Chabrier fu animatore dei circoli parnassiani, dove fece amicizia con C. Méndes, J. Richepin, E. Rostand, P. Verlaine. Era anche intimo di E. Manet (posò due volte per lui, nel 1880 e nel 1881). -

Pdf Magdalena Wąsowska, Gwendoline Emmanuela Chabriera

Magdalena Wąsowska Gwendoline Emmanuela Chabriera 1 Francuska kultura muzyczna w II połowie XIX wieku pozostawała pod silnym wpływem osiągnięć artystycznych Wagnera. W literaturze muzykolo- gicznej 2 obok Fervaala Vincenta d’Indy’ego i Le Roi Arthus Ernesta Chaus- sona opera Gwendoline Emmanuela Chabriera jest jednym z najczęściej po- dawanych przykładów przeszczepienia założeń dramatycznych Wagnera do muzyki francuskiej. Celem niniejszego artykułu jest zaprezentowanie opery Gwendoline jako przykładu zaadoptowania jednego z podstawowych elemen- tów systemu muzycznego Wagnera — leitmotywu, do techniki kompozytor- skiej francuskiego twórcy. Równolegle do przemian w ramach gatunku opery w Europie w XIX wie- ku, we francuskiej twórczości operowej kształtują się różne nurty stylistyczne. W latach 1830–1870 dominował repertuar typu grand opéra. Stałą popu- larnością cieszyły się m.in. La Muette de Portici Aubera (1828), Wilhelm Tell Rossiniego (1829), Robert le diable (1831) i Les Huguenots (1836) Meyerbeera 1 Artykuł opracowany na podstawie pracy magisterskiej pt. „Gwendoline” Emmanuela Chabriera w kontekście recepcji Wagnera we Francji w XIX wieku, napisanej pod kierunkiem prof. dr hab. Małgorzaty Woźnej-Stankiewicz, Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Instytut Muzykologii, Kra- ków 2003, mps. 2 M.in. Danièle Pistone, Emmanuel Chabrier, Opera Composer, tłum. ang. E. T. Glasow, „Opera Quarterly”, t. 12, 1996, s. 17–25; Theo Hirsbrunner, Die Musik in Frankreich im 20. Jahrhundert, cz I. 1871–1918, Laaber 1995; Robert Delage, Chabrier et Wagner, „Revue de Mu- sicologie”, t. 82, 1996, s. 167–179, Rollo Myers, Emmanuel Chabrier and his circle, London 1996; Steven Huebner, French Opera at the Fin de Siècle. Wagnerism, Nationalism and Style, New York 1999; Manuela Schwartz, Wagner-Rezeption und französische Oper des Fin de siècle.