Changing the Scripts: Midlife Women's Sexuality in Contemporary U.S. Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

Senior Women's Performances of Sexuality

“DUSTY MUFFINS”: SENIOR WOMEN’S PERFORMANCES OF SEXUALITY A Thesis by EVLEEN MICHELLE NASIR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies “Dusty Muffins”: Senior Women’s Performances of Sexuality Copyright 2012 Evleen Michelle Nasir “DUSTY MUFFINS”: SENIOR WOMEN’S PERFORMANCES OF SEXUALITY A Thesis by EVLEEN MICHELLE NASIR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, Judith Hamera Harry Berger Alfred Bendixen Head of Department, Judith Hamera August 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies iii ABSTRACT “Dusty Muffins”: Senior Women’s Performance of Sexuality. (August 2012) Evleen Michelle Nasir, B.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Kirsten Pullen There is a discursive formation of incapability that surrounds senior women’s sexuality. Senior women are incapable of reproduction, mastering their bodies, or arousing sexual desire in themselves or others. The senior actresses’ I explore in the case studies below insert their performances of self and their everyday lives into the large and complicated discourse of sex, producing a counter-narrative to sexually inactive senior women. Their performances actively embody their sexuality outside the frame of a character. This thesis examines how senior actresses’ performances of sexuality extend a discourse of sexuality imposed on older woman by mass media. These women are the public face of senior women’s sexual agency. -

776-SELL Only.Nodealers/Businesses 29 Good for Auto, Boat &RV!

Saturday, September 26, 2020 The Eagle ● theeagle.com B3 SATURDAY EVENING A Suddenlink B DirecTV C Dish Network SEPTEMBER 26, 2020 A B C 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 (2:30) NCAA Football (L) 'TVG' Football Football Pre-game (L) /(:35) NCAA Football Florida State at Miami Site: Hard (:50) 13 News (:35) Extra (:05) (:35) Ins. (:05) Wipeout 'TVPG' (13) KTRK 3-- Score. (L) Score. (L) Rock Stadium--Miami Gardens, Fla. (L)'TVG' Scoreb. at 10 (N) Points Texans Ed. (N) Cook's Into the Museum Newsho- The Parks and Bluegrass F.Drake "Healing Midsomer (:35) Midsomer Appear- Austin City Limits Bluegrass AChef's Nova "A to Z: The (15) KAMU 41512 Country Outdoors Access ur. (N) Bookmark Wildlife Under Hands" 'TV14' Murders Murders 'TVPG' ances "Billie Eilish" 'TVPG' Under Life First Alphabet" 'TVG' (2:30) NCAA Football Mississippi State University at News 3at Bucket Bull "The Sovereigns" S.W.A.T. 'TV14' 48 Hours 'TVPG' News 3at (:35) NCIS: New (:35) Castle "Head (:35) NCIS (3) KBTX 5350 Louisiana State University Site: Tiger Stadium(L) 'TVG' 6Sat. (N) List (N) 'TV14' 10 (N) Orleans 'TV14' Case" 'TVPG' Friends Friends Friends Mike & Mike & Two and a Two and a Pawn Pawn Pawn Pawn ABC13Eyewitness Amer.Ninja "Houston Am.Ninja "Pittsburgh ABC 13 Eyewitness (39) KIAH --- Molly Molly Half Men Half Men Stars Stars Stars Stars (N) Finals"2/2 'TVPG' Finals" 'TVPG' News at 9:00 p.m. -

Juliet Ouyoung 917-528-9764

Feb. 2015 Page #1 of 2 Juliet Ouyoung 917-528-9764 www.jouyoung.com Costume Designer Assistant Costume Designer The Shanghai Hotel 2006 Late Show With David Letterman 2006-2015 Feature / Cornucopia Productions Talk –Variety TV Show \ CBS – Worldwide Pants INC. 2006 Contemporary Drama/ Human Trafficking Fast Paste Sketch Characters \ Comedy Hill Harper, Pei Pei Cheng, Eugenia Yuan Bruce Willis, Steve Martin, Martin Short, Bill Murray,Chris Elliott Jerry Davis, Director Jerry Foley , Director ; Sue Hum, CD Neurotica 2000 Bernard & Doris 2005 Feature / Three Forks Productions Feature / Trigger Street Productions 2000 Contemporary Comedy / Road Trip 1980’s-1990’s Drama / Doris Duke Biopic Brian D’Arcy James, Amy Sedaris Ralph Fiennes, Susan Sarandon Roger Rawlings, Director Bob Balaban, Director ; Joe Aulissi, CD Mob Queen 1997 Copshop 2003 Feature / Etoile Productions Pilot / PBS Television 1956 Comedy / Mafia Meets Transvestite 2003 Contemporary Drama / NYPD - Brothel Tony Sirico, David Proval, Candice Kane Richard Dreyfuss, Rosey Perez, Rita Moreno, Blair Brown Jon Carnoy, Director Anita Addison & Joe Cacaci , director ; Bobby Tilly, CD Harwood 1999 Like Mother Like Son 2002 Feature / Absolutely Legitimate Film MOW / CBS Televison 1999 Contemporary / Sci-fi Thriller 1998 Contemporary Drama / Sente Kimes’ Story Morgan Roberts, Director Mary Tyler Moore, Jean Stapleton Arthur Seidelman, Director; Martin Pakledinaz, CD The Floys Of Neighborly Lane 1998 Deconstructing Harry 1996 Short / Once Upon A Picture Production Feature / Sweetheart Productions -

Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance U.S

1 Check website or mobile app for full description and content information. description app for full Check website or mobile #sundance • sundance.org/festival sundance.org/festival Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance The U.S. Dramatic Competition Films As You Are The Birth of a Nation U.S. Dramatic Competition Dramatic U.S. Many of these films have not yet been rated by the Motion Picture Association of America. Read the full descriptions online and choose responsibly. Films are generally followed by a Q&A with the director and selected members of the cast and crew. All films are shown in 35mm, DCP, or HDCAM. Special thanks to Dolby Laboratories, Inc., for its support of our U.S.A., 2016, 110 min., color U.S.A., 2016, 117 min., color digital cinema projection. As You Are is a telling and retelling of a Set against the antebellum South, this story relationship between three teenagers as it follows Nat Turner, a literate slave and traces the course of their friendship through preacher whose financially strained owner, PROGRAMMERS a construction of disparate memories Samuel Turner, accepts an offer to use prompted by a police investigation. Nat’s preaching to subdue unruly slaves. Director, Associate Programmers Sundance Film Festival Lauren Cioffi, Adam Montgomery, After witnessing countless atrocities against 2 John Cooper Harry Vaughn fellow slaves, Nat devises a plan to lead his DIRECTOR: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte people to freedom. Director of Programming Shorts Programmers SCREENWRITERS: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte, Trevor Groth Dilcia Barrera, Emily Doe, Madison Harrison Ernesto Foronda, Jon Korn, PRINCIPAL CAST: Owen Campbell, DIRECTOR/SCREENWRITER: Nate Parker Senior Programmers Katie Metcalfe, Lisa Ogdie, Charlie Heaton, Amandla Stenberg, PRINCIPAL CAST: Nate Parker, David Courier, Shari Frilot, Adam Piron, Mike Plante, Kim Yutani, John Scurti, Scott Cohen, Armie Hammer, Aja Naomi King, Caroline Libresco, John Nein, Landon Zakheim Mary Stuart Masterson Jackie Earle Haley, Gabrielle Union, Mike Plante, Charlie Reff, Kim Yutani Mark Boone Jr. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

On Using Movies to Inform Conscious Aging Courses

On Using Movies to inform Conscious Aging Courses Over the past 4 years I have taught nine, eight-week Conscious Aging courses at Sydney University’s Centre for Continuing Education in Australia. In 2010, I attended the first International Sage-ing Conference in Denver, CO, where Judy Steiert (CSL) gave an inspiring presentation on using movies to inform the Sage-ing materials. I was hooked. Having taught a number of 8-week courses (2 hours/week) without the use of movies, I came home to Australia and designed a course around 8 movies. I extended each class to 3 hours, to allow the time to watch a movie each week and leave some time for discussion. Using movies is a powerful tool for illustrating Sage-ing themes and allows students to really ‘get’, with an emotional catharsis, the importance of the various processes described as necessary in the sage-ing journey. Students find it much easier to discuss and relate to the topics, when they’re portrayed in the lives of characters in a film, than having to find examples in their own experience. It gives them extra time and space to locate the emotions and events and do the required harvesting and healing work in their own lives. Fiction, speaks to deep truths in ourselves. By addressing universal themes, it also allows us to see that we are not alone; it points to the communion of all people and by holding up a mirror to our shared humanity, allows us to see ourselves more clearly. I have found using movies to illustrate and guide the discussion and exploration of the Sage-ing process extremely rewarding and wanted to share some information about the movies I have used with Sage- ing International members. -

ANNETTE BENING Miramar College a Star Is Born at Mesa College

WITH EXCELLENCE SAN DIEGO COMMUNITY COLLEGE DISTRICT FALL 2018 City College Mesa College ANNETTE BENING Miramar College A Star is Born at Mesa College Continuing Education Story on page 06 CHANCELLOR’S MESSAGE KEEPING THE PROMISE On September 20, we made great strides in the Now in its third year of operation, the San Diego ongoing fundraising campaign for the San Diego Promise has grown from 186 students in 2016 to Promise in a special gala event, which was headlined more than 2,100 students today who meet the criteria by Mesa College alumna and film and theatre star of being first-time, full-time students taking 12 or Annette Bening. The event was a resounding success, more units. These students benefit from the waiver of raising over $200,000, which was $100,000 more than tuition and fees, and also are provided textbook grants the goal, with all proceeds benefiting students in the in recognition of the fact that textbooks can be more Promise program. This funding has been added to the expensive than the cost of enrollment. $820,000 that has been raised thus far. We are deeply This unprecedented opportunity is possible in grateful to Ms. Bening for her devotion to our efforts large part because of donors, both large and small, to serve community college students. She has given throughout the San Diego region, including hundreds a great boost to the second phase of our fundraising of San Diego Community College District employees campaign. who contribute through the payroll deduction option. Although the first year of the San Diego Promise is now financed through state funding provided under Assembly Bill 19, the second year of the San Diego Promise program and the additional benefits are funded entirely through philanthropy. -

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

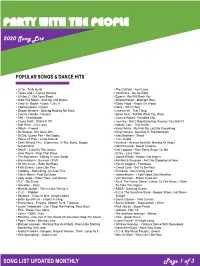

View the Full Song List

PARTY WITH THE PEOPLE 2020 Song List POPULAR SONGS & DANCE HITS ▪ Lizzo - Truth Hurts ▪ The Outfield - Your Love ▪ Tones And I - Dance Monkey ▪ Vanilla Ice - Ice Ice Baby ▪ Lil Nas X - Old Town Road ▪ Queen - We Will Rock You ▪ Walk The Moon - Shut Up And Dance ▪ Wilson Pickett - Midnight Hour ▪ Cardi B - Bodak Yellow, I Like It ▪ Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood ▪ Chainsmokers - Closer ▪ Nelly - Hot In Here ▪ Shawn Mendes - Nothing Holding Me Back ▪ Lauryn Hill - That Thing ▪ Camila Cabello - Havana ▪ Spice Girls - Tell Me What You Want ▪ OMI - Cheerleader ▪ Guns & Roses - Paradise City ▪ Taylor Swift - Shake It Off ▪ Journey - Don’t Stop Believing, Anyway You Want It ▪ Daft Punk - Get Lucky ▪ Natalie Cole - This Will Be ▪ Pitbull - Fireball ▪ Barry White - My First My Last My Everything ▪ DJ Khaled - All I Do Is Win ▪ King Harvest - Dancing In The Moonlight ▪ Dr Dre, Queen Pen - No Diggity ▪ Isley Brothers - Shout ▪ House Of Pain - Jump Around ▪ 112 - Cupid ▪ Earth Wind & Fire - September, In The Stone, Boogie ▪ Tavares - Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel Wonderland ▪ Neil Diamond - Sweet Caroline ▪ DNCE - Cake By The Ocean ▪ Def Leppard - Pour Some Sugar On Me ▪ Liam Payne - Strip That Down ▪ O’Jay - Love Train ▪ The Romantics -Talking In Your Sleep ▪ Jackie Wilson - Higher And Higher ▪ Bryan Adams - Summer Of 69 ▪ Ashford & Simpson - Ain’t No Stopping Us Now ▪ Sir Mix-A-Lot – Baby Got Back ▪ Kenny Loggins - Footloose ▪ Faith Evans - Love Like This ▪ Cheryl Lynn - Got To Be Real ▪ Coldplay - Something Just Like This ▪ Emotions - Best Of My Love ▪ Calvin Harris - Feel So Close ▪ James Brown - I Feel Good, Sex Machine ▪ Lady Gaga - Poker Face, Just Dance ▪ Van Morrison - Brown Eyed Girl ▪ TLC - No Scrub ▪ Sly & The Family Stone - Dance To The Music, I Want ▪ Ginuwine - Pony To Take You Higher ▪ Montell Jordan - This Is How We Do It ▪ ABBA - Dancing Queen ▪ V.I.C. -

Wakana Yoshihara Hair and Make up Designer

WAKANA YOSHIHARA HAIR AND MAKE UP DESIGNER FILM & TELEVISION THE MARVELS Director: Nia DaCosta Production Company: Marvel Cast: Brie Larson, Zawe Ashton, Teyonah Parris, Iman Vellani SPENCER Director: Pablo Larraín Production Company: Fabula Films, Komplizen Film, Shoebox Films Cast: Kristen Stewart, Sally Hawkins, Timothy Spall, Sean Harris Official Selection, Venice Film Festival (2021) BELFAST Director: Kenneth Branagh Production Company: Focus Features Cast: Caitriona Balfe, Judi Dench, Jamie Dornan, Ciaran Hinds, Jude Hill Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2021) DEATH ON THE NILE Director: Kenneth Branagh Production Company: Twentieth Century Fox Film Cast: Annette Bening, Gal Gadot, Armie Hammer, Letitia Wright, Tom Bateman EARTHQUAKE BIRD Director: Wash Westmoreland Production Company: Netflix & Scott Free Productions Cast: Alicia Vikander, Riley Keough, Jack Huston Official Selection, London Film Festival (2019) ARTEMIS FOWL Director: Kenneth Branagh Production Company: Walt Disney Pictures Cast: Judi Dench LUX ARTISTS | 1 FARMING Director: Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje Production Company: Groundswell Productions Cast: Kate Beckinsale, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje Winner, Michael Powell Award for Best British Feature Film, Edinburgh Film Festival (2019) Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2018) MURDER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS (Head of Hair & Make-up) Director: Kenneth Branagh Production Company: Twentieth Century Fox Film Cast: Johnny Depp, Daisy Ridley, Judi Dench BLACK MIRROR: PLAYTEST Director: Dan Trachtenberg