Beethoven, Piano Trio in C Minor, Op. 1 No. 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

Ax/Kavakos/Ma Trio Sunday 9 September 2018 3Pm, Hall

Ax/Kavakos/Ma Trio Sunday 9 September 2018 3pm, Hall Brahms Piano Trio No 2 in C major Brahms Piano Trio No 3 in C minor interval 20 minutes Brahms Piano Trio No 1 in B major Emanuel Ax piano Leonidas Kavakos violin Yo-Yo Ma cello Part of Barbican Presents 2018–19 Shane McCauley Programme produced by Harriet Smith; printed by Trade Winds Colour Printers Ltd; advertising by Cabbell (tel. 020 3603 7930) Confectionery and merchandise including organic ice cream, quality chocolate, nuts and nibbles are available from the sales points in our foyers. Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know The City of London during your visit. Additional feedback can be given Corporation is the founder and online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods principal funder of located around the foyers. the Barbican Centre Welcome A warm welcome to this afternoon’s incarnation that we hear today. What is concert, which marks the opening of the striking is how confidently Brahms handles Barbican Classical Music Season 2018–19. the piano trio medium, as if undaunted by the legacy left by Beethoven. The concert brings together three of the world’s most oustanding and Trios Nos 2 and 3 both date from the 1880s charismatic musicians: pianist Emanuel and were written during summer sojourns Ax, violinist Leonidas Kavakos and – in Austria and Switzerland respectively. cellist Yo-Yo Ma. They perform the three While the Second is notably ardent and piano trios of Brahms, which they have unfolds on a large scale, No 3 is much recorded to great critical acclaim. -

RICE UNIVERSITY Beethoven's Triple Concerto

RICE UNIVERSITY Beethoven's Triple Concerto: A New Perspective on a Neglected Work by Levi Hammer A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFULLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE: Master of Music APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: Brian Connelly, Artist Teacher of Shepherd School of Music Richard Lavenda, Professor of Composition, Chair Shepherd School of Music Kfrl11eti1Goldsmith, Professor of Violin Shepherd School of Music Houston, Texas AUGUST2006 ABSTRACT Beethoven's Triple Concerto: A New Perspective on a Neglected Work by Levi Hammer Beethoven's Triple Concerto for piano, violin, and violoncello, opus 56, is one of Beethoven's most neglected pieces, and is performed far less than any of his other works of similar scope. It has been disparaged by scholars, critics, and performers, and it is in need of a re-evaluation. This paper will begin that re-evaluation. It will show the historical origins of the piece, investigate the criticism, and provide a defense. The bulk of the paper will focus on a descriptive analysis of the first movement, objectively demonstrating its quality. It will also discuss some matters of interpretive choice in performance. This thesis will show that, contrary to prevailing views, the Triple Concerto is a unique and significant masterpiece in Beethoven's output. CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: General History of Opus 56 2 Beethoven in 1803-1804 Disputed Early Performance History Current Neglect History of Genre Chapter 3: Criticism and Defense I 7 Generic Criticism Thematic Criticism Chapter 4: Analysis of the First Movement 14 The Concerto Principle Descriptive Analysis Analytic Conclusions Chapter 5: Criticism and Defense II 32 Awkwardness and Prolixity Chapter 6: Miscellany and Conclusions 33 Other Movements and Tempo Issues Other Thoughts on Performance Conclusions Bibliography 40 1 Chapter 1: Introduction The time is 1803, the onset of Beethoven's heroic middle period, and the time of his most fervent work and most productive years. -

“Stolen Music” Debussy Prélude À L’Après-Midi D’Un Faune, Arr

Press Release For immediate release Linos Piano Trio Prach Boondiskulchok (piano) Konrad Elias-Trostmann (violin) Vladimir Waltham (cello) “Stolen Music” Debussy Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, arr. Linos Piano Trio Dukas L’apprenti sorcier, arr. Linos Piano Trio Schönberg Verklärte Nacht, arr. Eduard Steuermann Ravel La Valse, arr. Linos Piano Trio Watch the Introductory Video CAvi-music in partnership with the Bayerischer Rundfunk Cat. No: AVI_8553035 Release: 18 June 2021 This new recording from the Linos Piano Trio presents four iconic works from the turn of the 20th Century. The three French works, transcribed for piano trio by the Linos players themselves, are recorded for the first time here, while the Verklärte Nacht arrangement harks back to the inception of the Linos Piano Trio in 2007. Transcriptions have long served as a precursor to modern day recordings. Works for larger ensembles were transcribed for smaller groups to make music at home, and the piano trio was among the favourite combinations for this purpose, with its rich sonic possibilities apt at recreating the orchestral sound. This aspect of the genre has fascinated the Linos Piano Trio from the beginning, its first ever performance being of Schönberg’s Verklärte Nacht in the arrangement by Eduard Steuermann. Since 2016, the Linos Piano Trio has been taking this idea further, creating a series of its own transcriptions with the aim of reimagining each work as if originally conceived for piano trio. The transcriptions are all created collaboratively, evolving through experimentation and refinement, seeking the most colourful distillation of the original versions. -

PROGRAM NOTES the Level of Intimacy Is Even More Pronounced in the Third Movement, Aptly Named Tears and Specifically Inspired by Words from the Russian Poet Tyutchev

JANUARY 29, 2016 – 7:30 PM FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano in G Major, Hob. XV:25, “Gypsy” Andante Poco adagio cantabile Gypsy Rondo Andrew Wan violin / Astrid Schween cello / Anton Nel piano ALEXANDER BORODIN String Quintet in F minor Allegro con brio Andante ma non troppo Menuetto Finale: Prestissimo—Adagio—Prestissimo Tessa Lark violin / Scott Yoo violin / Che-Yen Chen viola / Bion Tsang cello / Yegor Dyachkov cello INTERMISSION SERGEI RACHMANINOFF Suite No. 1 for Two Pianos, Op. 5, “Fantaisie-tableaux” Barcarole A Night for Love Tears Russian Easter Gloria Chien piano / William Wolfram piano SEASON SPONSORSHIP PROVIDED BY DIANA CAREY FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN energetic rondo theme alternating with a series (1732–1809) of similarly scurrying episodes, the music hurtles Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano in G Major, forward with unstoppable momentum. Hob. XV:25, “Gypsy” (1795) ALEXANDER BORODIN Franz Joseph Haydn, whose combined string (1833–1887) quartets and symphonies account for almost 200 String Quintet in F minor (1853–54) works in his ample canon, wrote 45 piano trios plus more than a hundred others for the extinct Alexander Borodin was undoubtedly history’s most baryton (the cello-like instrument played by the successful amateur composer, treating music as a composer’s employer at the Esterháza estate in beloved hobby secondary to his dual profession as Hungary). Note that his piano trios fall under the a chemist and surgeon. His musical education was heading “Keyboard Music” in the current Grove scanty, that in chemistry quite the contrary. Scientific Dictionary. Why? Simply because until the trios journals of the time praised his scientific work, of Beethoven and Schubert, the cello and violin while fellow composers—spurred by the advocacy parts were more-or-less discretionary, in large of Balakirev—applauded his musical efforts. -

Guide to Repertoire

Guide to Repertoire The chamber music repertoire is both wonderful and almost endless. Some have better grips on it than others, but all who are responsible for what the public hears need to know the landscape of the art form in an overall way, with at least a basic awareness of its details. At the end of the day, it is the music itself that is the substance of the work of both the performer and presenter. Knowing the basics of the repertoire will empower anyone who presents concerts. Here is a run-down of the meat-and-potatoes of the chamber literature, organized by instrumentation, with some historical context. Chamber music ensembles can be most simple divided into five groups: those with piano, those with strings, wind ensembles, mixed ensembles (winds plus strings and sometimes piano), and piano ensembles. Note: The listings below barely scratch the surface of repertoire available for all types of ensembles. The Major Ensembles with Piano The Duo Sonata (piano with one violin, viola, cello or wind instrument) Duo repertoire is generally categorized as either a true duo sonata (solo instrument and piano are equal partners) or as a soloist and accompanist ensemble. For our purposes here we are only discussing the former. Duo sonatas have existed since the Baroque era, and Johann Sebastian Bach has many examples, all with “continuo” accompaniment that comprises full partnership. His violin sonatas, especially, are treasures, and can be performed equally effectively with harpsichord, fortepiano or modern piano. Haydn continued to develop the genre; Mozart wrote an enormous number of violin sonatas (mostly for himself to play as he was a professional-level violinist as well). -

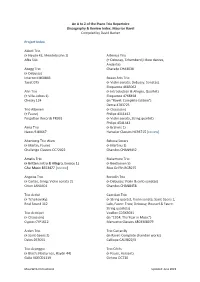

Ravel Compiled by David Barker

An A to Z of the Piano Trio Repertoire Discography & Review Index: Maurice Ravel Compiled by David Barker Project Index Abbot Trio (+ Haydn 43, Mendelssohn 1) Artenius Trio Afka 544 (+ Debussy, Tchemberdji: Bow dances, Andante) Abegg Trio Charade CHA3038 (+ Debussy) Intercord 860866 Beaux Arts Trio Tacet 075 (+ Violin sonata; Debussy: Sonatas) Eloquence 4683062 Ahn Trio (+ Introduction & Allegro, Quartet) (+ Villa-Lobos 1) Eloquence 4768458 Chesky 124 (in “Ravel: Complete Edition”) Decca 4783725 Trio Albeneri (+ Chausson) (+ Faure) Philips 4111412 Forgotten Records FR991 (+ Violin sonata, String quartet) Philips 4541342 Alma Trio (+ Brahms 1) Naxos 9.80667 Hanssler Classics HC93715 [review] Altenberg Trio Wien Bekova Sisters (+ Martin, Faure) (+ Martinu 1) Challenge Classics CC72022 Chandos CHAN9452 Amatis Trio Blakemore Trio (+ Britten: Intro & Allegro, Enescu 1) (+ Beethoven 5) CAvi Music 8553477 [review] Blue Griffin BGR275 Angelus Trio Borodin Trio (+ Cortes, Grieg: Violin sonata 2) (+ Debussy: Violin & cello sonatas) Orion LAN0401 Chandos CHAN8458 Trio Arché Caecilian Trio (+ Tchaikovsky) (+ String quartet, Violin sonata; Saint-Saens 1, Real Sound 112 Lalo, Faure: Trios; Debussy, Roussel & Faure: String quartets) Trio Archipel VoxBox CD3X3031 (+ Chausson) (in “1914: The Year in Music”) Cypres CYP1612 Menuetto Classics 4803308079 Arden Trio Trio Carracilly (+ Saint-Saens 2) (in Ravel: Complete chamber works) Delos DE3055 Calliope CAL3822/3 Trio Arpeggio Trio Cérès (+ Bloch: Nocturnes, Haydn 44) (+ Faure, Hersant) Gallo VDECD1119 Oehms -

John Wilson / Repertoire / Concerti

John Wilson / Repertoire / Concerti J.S. Bach Concerto No. 1 in D minor for Keyboard and String Orchestra, BWV 1052 Concerto for Flute, Violin and Keyboard in A minor, BWV 1044 Concerto for Two Harpsichords in C minor, BWV 1060 Barber Piano Concerto, Op. 38 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15 Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 19 Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37 Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, Op. 58 Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 73 Bernstein Symphony No. 2 “The Age of Anxiety” Brahms Piano Concerto No.1 in D minor, Op. 15 Chopin Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11 Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Copland Piano Concerto Cowell Piano Concerto Falla Concerto for Harpsichord Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue Piano Concerto in F Second Rhapsody Variations on ‘I Got Rhythm’ Grieg Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Lecuona Rapsodia Cubana Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat, S. 124 Piano Concerto No. 2 in A, S. 125 Totentanz, S 126 Macdowell Piano Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 23 Messiaen Oiseaux exotiques Turangalîla-Symphonie Mozart Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-flat major, K. 271 Piano Concerto No. 17 in B-flat major, K. 595 Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466 Poulenc Concerto for Two Pianos in d minor, FP 61 Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp minor, Op. 1 Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. -

Piano Trios for Tots Through Teens Catalog 20131210.Xlsx

Piano Trios for Tots through Teens: An Exploration of Piano, Violin and Cello Trios for the Beginning through Intermediate Levels Technical Level Piece/Collection Publisher Likeability Rating LHS/position Technical/Musical Features: Ensemble P V C Composer/Editor # of pno pgs P V C Key(s) Individual Instruments Highland Parade/The Empty Birdhouse and LME h6/1/1 P: crushed grace notes LE 1 1 Other Songs for Piano Trio VX-24 8 8 8 V: easy, open string double stops Critelli, Carol D 2 D C: no extensions, appealing, open string double stops Waltz, Op39, No13/Kabalevsky MM m8/1/1 P: keep LH double notes light and bouncy LE 2 2 Kammermusik 8 7 7 V: optional 3rd position (end of Bk 3) Kabalevsky, Dmitri/arr Joseph McSpadden 1.5 d C: The Empty Birdhouse/The Empty P: fun to play Birdhouse and Other Songs for Piano Trio LME m8/1/1 LE 2 3 8 8 8 V: Bk2-3 great key, balance between V and C VX-24 2 g, G C: easy, appealing Critelli, Carol D The Sleeping Cat/The Empty Birdhouse and LME m8/1/3 P: has a solo part LE 2 3 Other Songs for Piano Trio VX-24 8 8 8 V: mid-Bk2, key comes in 2 Grenadiers, easy double stops Critelli, Carol D 2 d C: simple, appealing, good balance Nothing to Do/Tunes for my Piano Trio 2 B&H m7/1/1 P: syncopation, difficult to count the rests 6/8 time LE 3 2 Nelson, Sheila M 6 8 6 V: rhythmically complex 3 B C: syncopation, rests (m52), otherwise technically simple LE/ FireplaCe/The Empty Birdhouse and Other LME h6/1/1 P: LH position changes, RH has a melodic 7th Great 1st chamber music piece. -

O Trio Para Piano, Violino E Violoncelo De Maurice Ravel a Partir Da Análise Do Autor

O Trio para piano, violino e violoncelo de Maurice Ravel a partir da análise do autor Danieli Verônica Longo Benedetti (UNICSUL) Resumo: O presente artigo discorre sobre o Trio para piano, violino e violoncelo escrito pelo compositor francês Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) às vésperas da Primeira Guerra Mundial, constituindo-se em obra de referência do movimento nacionalista francês. A partir de uma leitura atenta do manuscrito da análise da obra pelo próprio autor o artigo elucida alguns procedimentos composicionais ali adotados. Palavras-chave: Ravel; nacionalismo; análise; trio para piano. Abstract: This article concerns the Trio for piano, violin and cello by the French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). Written right before the First World War, this is a reference work of the French nationalist movement. A careful reading of a manuscript containing the analysis of this work by Ravel himself sheds light on some of his compositional procedures. Keywords: Ravel; nationalism; analysis; piano trio. BENEDETTI, Danieli Verônica Longo. O Trio para piano, violino e violoncelo de Maurice Ravel a partir da análise do autor. Opus, Goiânia, v. 15, n. 2, dez. 2009, p. 61-70. O Trio para piano, violino e violoncelo de Maurice Ravel . compositor Maurice Ravel deixaria documentada uma significativa contribuição musical durante os anos da Primeira Grande Guerra. Apesar das dificuldades vividas durante esse período – fragilidade física e psicológica, dificuldades materiais, O 1 insistente percurso para ser aceito às armas, morte dos amigos e da mãe – Ravel encontraria vitalidade para a composição do Trio para piano, violino e violoncelo, da letra e música das Trois Chansons para coro misto sem acompanhamento e da suíte para piano solo Le Tombeau de Couperin, aos moldes da suíte francesa do século XVIII.2 Tal produção confirmaria, assim como a de seus contemporâneos, o envolvimento estético com o movimento nacionalista, no qual podemos observar uma comunhão dos procedimentos de composição adotados. -

Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) Piano Trio No. 3 in F Minor Op. 65 (1883) Allegro, Ma Non Troppo Allegretto Grazioso – Meno Mosso Poco Adagio Finale

Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) Piano Trio No. 3 in F minor Op. 65 (1883) Allegro, ma non troppo Allegretto grazioso – meno mosso Poco Adagio Finale. Allegro con brio This piano trio dates from a similar time in Dvořák's life to the Op 61 quartet played by the Castalian at the beginning of the season. Prior to this time, Dvořák's music was Slavonic, folk-oriented, generally genial and carefree. But, as a result of an anti-Czech political mood in Austria, his Viennese audience had become “prejudiced against a composition with a Slav flavour” ( Dvořák to the conductor Richter, 1884). His new style, apparent both here and in the Seventh Symphony Op 70, was altogether darker and more dramatic. Another likely influence on this piano trio was the recent death of his mother. Whatever its background, the work was complex and masterful, full of intense contrasts - his finest chamber work yet. The first movement starts innocuously enough with the violin and cello very quietly in octaves. But two bars later they descend fortissimo from the heights in triplets into angry despair with spread chords. The cello then introduces a quiet, tender theme, and the movement continues on an elegiac, emotional roller coaster with a wealth of contrasting melodic material. The writing is complex, reminiscent of Schumann and of Dvořák's champion, Brahms. The scherzo-like Allegretto shifts the key down a third from the previous F minor into C# minor – actually Db minor in disguise, but Dvořák kindly gives the player only 4 sharps instead of 8 flats! Why does Dvořák write in these complicated keys? You'd never catch Mozart doing that. -

Anton Arensky Witold Lutosławski Maurice Ravel

JANUARY 31, 2016 – 3:00 PM ANTON ARENSKY Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano in D minor, Op. 32 Allegro moderato—Adagio Scherzo: Allegro molto Elegia: Adagio Finale: Allegro non troppo—Andante—Adagio—Allegro molto Scott Yoo violin / Astrid Schween cello / Gloria Chien piano WITOLD LUTOSŁAWSKI Variations on a Theme by Paganini for Two Pianos Anton Nel piano / William Wolfram piano MAURICE RAVEL La Valse for Two Pianos William Wolfram piano / Anton Nel piano INTERMISSION FRANZ SCHUBERT String Quintet in C Major, D. 956 Allegro ma non troppo Adagio Scherzo Allegretto Andrew Wan violin / Tessa Lark violin / Che-Yen Chen viola / Yegor Dyachkov cello / Bion Tsang cello ANTON ARENSKY The Finale: Allegro non troppo—Andante— (1861-1906) Adagio—Allegro molto leaps forward with an Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano in D minor, optimistic theme that alternates with material Op. 32 (1894) recalling the previous movement. Toward the end of the piece, Arensky slows the tempo and reprises Over the past few decades Anton Arensky’s the main theme of the first movement before music has finally begun to attract an audience concluding with a vigorous coda. concomitant with his talent. It was not always so. His mentor Rimsky-Korsakov summed up his WITOLD LUTOSŁAWSKI opinion of his former student thusly: “In his youth (1913–1994) Arensky did not escape some influence from me; Variations on a Theme by Paganini for Two later the influence came from Tchaikovsky. He Pianos (1941) will quickly be forgotten.” Not exactly a vote of confidence! Nonetheless, poor maligned Arensky In common with many of his central European eventually won a gold medal in 1882 from the St.