State Aids to Eu Seaports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ports: Definition and Study of Types, Sizes and Business Models

Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management JIEM, 2013 – 6(4): 1055-1064 – Online ISSN: 2013-0953 – Print ISSN: 2013-8423 http://dx.doi.org/10.3926/jiem.770 Ports: definition and study of types, sizes and business models Ivan Roa1 ,Yessica Peña1, Beatriz Amante1, María Goretti 2 1Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2Torrella Ingenieros (Spain) [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received: March 2013 Accepted: July 2013 Abstract: Purpose: In the world today there are thousands of port facilities of different types and sizes, competing to capture some market share of freight by sea, mainly. This article aims to determine the type of port and the most common size, in order to find out which business model is applied in that segment and what is the legal status of the companies of such infrastructure. Design/methodology/approach: To achieve this goal, we develop a research on a representative sample of 800 ports worldwide, which manage 90% of the containerized port loading. Then you can find out the legal status of the companies that manage them. Findings: The results indicate a port type and a dominant size, which are mostly managed by companies subject to a concession model. Research limitations/implications: In this research, we study only those ports that handle freight (basically containerized), ignoring other activities such as fishing, military, tourism or recreational. Originality/value: This is an investigation to show that the vast majority of the studied segment port facilities are governed by a similar corporate model and subject to pressure from the markets, which increasingly demand efficiency and service. -

Caribbean Port Services Industry: Towards the Efficiency Frontier Caribbean Development Bank

TRANSFORMING THE CARIBBEAN PORT SERVICES INDUSTRY: TOWARDS THE EFFICIENCY FRONTIER CARIBBEAN DEVELOPMENT BANK TRANSFORMING THE CARIBBEAN PORT SERVICES INDUSTRY: TOWARDS THE EFFICIENCY FRONTIER ISBN 978-976-95695-8-4 Published by the Caribbean Development Bank CONTENT 08 09 Foreword Executive Summary 17 19 1. Introduction 2. Port Efficiency and Bottlenecks 1.1 General introduction 17 2.1 Introduction to the Issue of 19 1.2 Objectives of the Study 17 Port Efficiency 1.3 Scope of the Study 18 2.2 Overview of Port Characteristics 21 1.4 Report Structure 18 2.3 Port Efficiency Score 33 2.4 Main Bottlenecks in Efficiency 41 2.5 Enhancing Port Efficiency 47 50 66 3. Container Trade Patterns 4. Port Development Options and Forecasts 4.1 Development Vision 66 3.1 Introduction to Container Transport 50 4.2 Development Options 68 in the Caribbean Basin 3.2 Overview of Container Ports in the Caribbean Region 52 3.3 Maritime Connectivity Ports 54 3.4 Future Development of Container Transport in the Caribbean 56 3.5 Traffic Forecast for the BMC Ports 63 74 81 5. Conclusions & Recommendations 6. Annex I – Port Fact Sheets 5.1 Conclusions 74 Port Factsheet – Antigua, St. John’s 82 5.2 Recommendations 79 Port Factsheet – Bahamas, Nassau 86 Port Factsheet – Barbados, Bridgetown 90 Port Factsheet – Belize, Belize Port 94 Port Factsheet – Dominica, Rosseau 98 Port Factsheet – Grenada, St. George’s 101 Port Factsheet – Guyana, Georgetown 106 Port Factsheet – Saint Kitts and Nevis, Basseterre 110 Port Factsheet – Saint Lucia, Castries 113 Port Factsheet – Saint Vincent and The Grenadines, Kingtown 117 Port Factsheet – Suriname, Paramaribo 121 Port Factsheet – Trinidad and Tobago, Port of Spain 125 130 Annex II – Sources Used List of Boxes 1. -

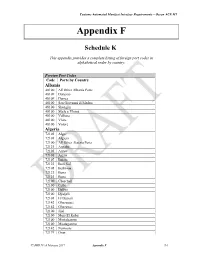

Appendix F – Schedule K

Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 Appendix F Schedule K This appendix provides a complete listing of foreign port codes in alphabetical order by country. Foreign Port Codes Code Ports by Country Albania 48100 All Other Albania Ports 48109 Durazzo 48109 Durres 48100 San Giovanni di Medua 48100 Shengjin 48100 Skele e Vlores 48100 Vallona 48100 Vlore 48100 Volore Algeria 72101 Alger 72101 Algiers 72100 All Other Algeria Ports 72123 Annaba 72105 Arzew 72105 Arziw 72107 Bejaia 72123 Beni Saf 72105 Bethioua 72123 Bona 72123 Bone 72100 Cherchell 72100 Collo 72100 Dellys 72100 Djidjelli 72101 El Djazair 72142 Ghazaouet 72142 Ghazawet 72100 Jijel 72100 Mers El Kebir 72100 Mestghanem 72100 Mostaganem 72142 Nemours 72179 Oran CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-1 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 72189 Skikda 72100 Tenes 72179 Wahran American Samoa 95101 Pago Pago Harbor Angola 76299 All Other Angola Ports 76299 Ambriz 76299 Benguela 76231 Cabinda 76299 Cuio 76274 Lobito 76288 Lombo 76288 Lombo Terminal 76278 Luanda 76282 Malongo Oil Terminal 76279 Namibe 76299 Novo Redondo 76283 Palanca Terminal 76288 Port Lombo 76299 Porto Alexandre 76299 Porto Amboim 76281 Soyo Oil Terminal 76281 Soyo-Quinfuquena term. 76284 Takula 76284 Takula Terminal 76299 Tombua Anguilla 24821 Anguilla 24823 Sombrero Island Antigua 24831 Parham Harbour, Antigua 24831 St. John's, Antigua Argentina 35700 Acevedo 35700 All Other Argentina Ports 35710 Bagual 35701 Bahia Blanca 35705 Buenos Aires 35703 Caleta Cordova 35703 Caleta Olivares 35703 Caleta Olivia 35711 Campana 35702 Comodoro Rivadavia 35700 Concepcion del Uruguay 35700 Diamante 35700 Ibicuy CAMIR V1.4 February 2017 Appendix F F-2 Customs Automated Manifest Interface Requirements – Ocean ACE M1 35737 La Plata 35740 Madryn 35739 Mar del Plata 35741 Necochea 35779 Pto. -

A Decision Support Tool for Port Planning Based on Monte Carlo Simulation

Proceedings of the 2018 Winter Simulation Conference M. Rabe, A. A. Juan, N. Mustafee, A. Skoogh, S. Jain, and B. Johansson, eds A DECISION SUPPORT TOOL FOR PORT PLANNING BASED ON MONTE CARLO SIMULATION Mª Izaskun Benedicto Javier Marino Rafael M. García Morales Ports and Coastal Engineering Departament Systems Division PROES Consultores FCC Industrial Calle General Yagüe 39 Calle Federico Salmón, 13 Madrid, 28020, SPAIN Madrid, 28016, SPAIN Francisco de los Santos Technological Development Area Algeciras Port Authority Av. de la Hispanidad, 2 Algeciras (Cádiz), 11207, SPAIN ABSTRACT Port planning and management has become a difficult task due to the increasing number of elements involved in port operations, their nature (random in some cases), and the relationships between them. Generally, traditional methods involving empirical formulas or queuing theory can be useful though only for simple cases. In the case of complex systems, the problem needs to be approached from a holistic point of view, and more advanced methodologies should be considered. In such cases, simulation may be the most appropriate solution, especially nowadays, when computation and data management are increasingly more efficient. A methodology for port planning and management, based on Monte Carlo simulation, is presented in this paper. A new software application, OptiPort, has been developed based on this methodology, proposed for use by port managers and planners. The methodology and the software have been validated with real data from the Port of Algeciras. 1 INTRODUCTION International shipping trade and, therefore, port activity, has increased dramatically in recent decades. Harbors have become dynamic places where many operations are performed simultaneously and with many interrelated elements, some of which have a random nature. -

Port Privatisation: Ownership Involvement by External Companies

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MARITIME SCIENCE MASTER DISSERTATION Academic year 2017 – 2018 Port privatisation: Ownership involvement by external companies Alan Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements Supervisor: Prof. dr. Theo Notteboom for the degree of: Master of Science in Maritime Science Assessor: Prof. Daan Schalck PERMISSION I declare that the content of this Master dissertation may be consulted or reproduced, provided that the source is referenced. Alan Johnson PREFACE This Master dissertation marks the conclusion of my advanced studies in the Master of Science in Maritime Science. I would like to explicitly thank certain people who have contributed to the realisation of this thesis. In the first place, I wish to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Prof. dr. Theo Notteboom and co-promotor Prof. Daan Schalck for their confidence and valuable feedback. Their willingness and assistance have resulted in the accomplishment of this dissertation. Furthermore, my appreciation goes to the interviewees for their cooperation and insights as well as to the respondents for completing the survey regarding my qualitative research. Many thanks go to my friends who are always available for advice. Their relentless and unconditional enthusiasm mean a lot to me. Last but not least, I am deeply grateful to my parents for the opportunity they have offered me to follow and finalise this additional master programme. Their exceptional support and motivation are extremely valuable for me. Alan Johnson Ghent, 24 January 2018 I II -

Policy Roundtable: Competition in Ports and Port Services 2011

Competition in Ports and Port Services 2011 The OECD Competition Committee debated competition in ports and port services in June 2011. This document includes an executive summary of that debate and the documents from the meeting: an analytical note by the OECD Secretariat and written submissions from Bulgaria, Chile, Estonia, Finland, the European Union, France, Germany, Indonesia, Italy, Mexico, Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, the Russian Federation, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Chinese Taipei, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States (Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission), as well as an aide-memoire of the discussion. Ports, whether maritime, inland or river ports, are important pieces of infrastructure that serve a wide range of customers including freight shippers, ferry operators and private boats. One of the main functions of ports is facilitating the domestic and international trade of goods, often on a large scale. Competition in maritime ports and port services is central to countries with significant volumes of maritime- based trade. Inland and river ports can also play important transport roles within countries in particular for heavy or bulky goods where alternative ways of transport are more costly. Ports are, therefore, important for the functioning of the world economy and effective competition in ports and port services plays an important role in the final prices of many products. The roundtable discussion focussed on market definition, regulatory reforms and antitrust enforcement in ports -

Alternative Port Management Structures and Ownership Models

PORT REFORM TOOLKIT SECOND EDITION MODULE 3 ALTERNATIVE PORT MANAGEMENT STRUCTURES AND OWNERSHIP MODELS THE WORLD BANK © 2007 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank All rights reserved. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF) or the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. Neither PPIAF nor the World Bank guarantees the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of PPIAF or the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this work is copyrighted. Copyright is held by the World Bank on behalf of both the World Bank and PPIAF. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including copying, recording, or inclusion in any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the World Bank. MODULE 3 The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission promptly. For all other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, please contact the Office of the Publisher, World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. ISBN-10: 0-8213-6607-6 ISBN-13: 978-0-8213-6607-3 eISBN: 0-8213-6608-4 eISBN-13: 978-0-8213-6608-0 DOI: 10.1596/978-0-8213-6607-3 MODULE THREE CONTENTS 1. -

Improving the Performance of Dry and Maritime Ports by Increasing Knowledge About the Most Relevant Functionalities of the Terminal Operating System (TOS)

sustainability Article Improving the Performance of Dry and Maritime Ports by Increasing Knowledge about the Most Relevant Functionalities of the Terminal Operating System (TOS) Miguel Hervás-Peralta 1,*, Sara Poveda-Reyes 1 , Gemma Dolores Molero 1, Francisco Enrique Santarremigia 1 and Juan-Pascual Pastor-Ferrando 2 1 AITEC Research & Innovation Projects, Parque Tecnológico C/Charles Robert Darwin 20, 46980 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] (S.P.-R.); [email protected] (G.D.M.); [email protected] (F.E.S.) 2 Universitat Politècnica de València, Camino de Vera s/n., 46022 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-961-366-969 Received: 5 February 2019; Accepted: 15 March 2019; Published: 19 March 2019 Abstract: Maritime transport in the European Union has increased in the last years, triggering congestion in many of the most important sea and river ports. A lot of works have highlighted how the connection between these ports and dry ports can contribute to reducing port congestion and emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs). This work aims to improve the knowledge about the functionalities of Terminal Operating Systems (TOSs) managing container terminals of sea, river, and dry ports, with the aim of improving their performance and contributing to reducing congestion and GHG emissions to achieve a higher sustainability. The contribution and novelty of this paper in the field of container-terminals logistics research is the use of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to identify and hierarchize TOS functionalities. The robustness of the model was checked by applying a sensitivity analysis. One hundred and seven functionalities were grouped into six main clusters: Warehouse, Maritime Operations, Gate, Master Data, Communications, and ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) Dashboard. -

IHR Authorized Ports List

IHR Authorized Ports List List of ports and other information submitted by the States Parties concerning ports authorized to issue Ship Sanitation Certificates under the International Health Regulations (2005) All States Parties to the International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR (2005)) are required to send to the World Health Organization (WHO) a list of all ports authorized by the State Party (including authorized ports in all of its applicable administrative areas and territories) to issue the following Ship Sanitation Certificates (SSC): - Ship Sanitation Control Certificates only (SSCC) and the provisions of the services referred to in Annex 1 and 3 - Ship Sanitation Control Exemption Certificates (SSCEC) only - Extensions to the SSC This list of authorized ports and other information is comprised of information submitted by the States Parties to WHO; WHO publishes this information in accordance with the requirements of the IHR (2005). This list will be updated by WHO as additional information is received from the States Parties. For further information on SSC please see: http://www.who.int/csr/ihr/travel/TechnAdvSSC.pdf Sources of codes and port location information. This listing utilizes information from the UN/LOCODE (United Nations Code for Trade and Transport Locations), published by UNECE (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe), as further modified by WHO. These UNLOCODE publications include ISO (International Organization for Standardization) codes and port location information. Notices. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this document, or in the underlying UN/LOCODE or ISO information sources, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city, area or location or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or borders. -

Multi-Agent Systems for Container Terminal Management

CONTAINER TERMINAL MANAGEMENT CONTAINER FOR SYSTEMS MULTI-AGENT ABSTRACT This thesis describes research concerning the app- In order to evaluate the multi-agent based sys- lication of multi-agent based simulation for evalua- tems approach, a simulation tool, called SimPort, MULTI-AGENT SYSTEMS FOR CONTAINER ting container terminal management operations. was developed for evaluating container terminal The growth of containerization, i.e., transporting management policies. The methods for modelling TERMINAL MANAGEMENT goods in a container, has created problems for the entities in a container terminal are presen- ports and container terminals. For instance, many ted along with the simulation experiments con- container terminals are reaching their capacity li- ducted. The results indicate that certain policies mits and increasingly leading to traffic and port can yield faster ship turn-around times and that congestion. Container terminal managers have certain stacking policies can lead to improved several, often conflicting goals, such as serve a productivity. Moreover, a multi-agent based simu- container ship as fast as possible while minimizing lation approach is used to evaluate a new type of terminal equipment costs Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) using a cas- sette system, and compare it to a traditional AGV The focus of the research involves the performan- system. The results suggest that the cassette-ba- Lawrence Edward Henesey ce from the container terminal manager’s per- sed system is more cost efficient than a traditional spective and how to improve the understanding AGV system in certain configurations. Finally, an of the factors of productivity and how they are re- agent-based approach is investigated for evalua- lated to each other. -

REVIEW of MARITIME TRANSPORT 2020 Iii

ii © 2020, United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Centre at copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licences, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: United Nations Publications 300 East 42nd Street New York, New York 10017 United States of America Email: [email protected] Website: un.org/publications The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States. The designations employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of any firm or licensed process does not imply the endorsement of the United Nations. United Nations publication issued by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development UNCTAD/RMT/2020 ISBN 978-92-1-112993-9 eISBN 978-92-1-005271-9 ISSN 0566-7682 eISSN 2225-3459 Sales No. E.20.II.D.31 REVIEW OF MARITIME TRANSPORT 2020 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Review of Maritime Transport 2020 was prepared by UNCTAD under the overall guidance of Shamika N. Sirimanne, Director of the Division on Technology and Logistics of UNCTAD, and under the coordination of Jan Hoffmann, Chief of the Trade Logistics Branch. Administrative and editorial support was provided by Wendy Juan. -

ROM 5.1-13 (EN).Pdf

Prologue The need to establish standardised operational protocols in the area of maritime engineering has resulted in the development of the ROM (Recomendaciones de Obras Marítimas – Maritime Works Recom- mendations) Program. The constitution of the Technical Commission responsible for its development in 1987 commenced the drawing up of a series of technical standards that establish the execution procedures, methods and criteria in maritime and port works executed in state-owned ports. The range of subjects in the Recommendations required them to be structured into seven thematic series: Series 0: Definition and classification of the project situation and factors in maritime and port works. Series 1: Shelter works against sea oscillations. Series 2: Mooring works project and execution. Series 3: Planning, project, management and operation of port areas. Series 4: Land-based superstructures and installations in the port areas. Series 5: Maritime and port works in the coastal environment. Series 6: Technical, administrative and legal provisions. Among these, Series 5, Maritime and Port Works in the Coastal Environment, covers the recom- mendations aimed at the development of Environmental Impact Studies (ROM 5.0), Coastal Maritime and Port Works (ROM 5.2), Dredging and filling (ROM 5.3) and the development of this document: ROM 5.1, Coastal Water Quality in Port Areas. Within this framework, ROM 5.1-05 was published in 2005 to tackle the problems involved in port water, within the spirit and principles established by the EU Water Framework Directive (2000/60/CE): “To establish a framework for the protection of continental surface waters, transitional waters, coastal waters and groundwaters”, all this, taking into account that the port aspects and activities must be present in the general planning as well as in the manner in which to tackle the aquatic system problems and management.