Biodiversity Conservation and Human Health: Exercise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freshwater Snails of Biomedical Importance in the Niger River Valley

Rabone et al. Parasites Vectors (2019) 12:498 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3745-8 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access Freshwater snails of biomedical importance in the Niger River Valley: evidence of temporal and spatial patterns in abundance, distribution and infection with Schistosoma spp. Muriel Rabone1* , Joris Hendrik Wiethase1, Fiona Allan1, Anouk Nathalie Gouvras1, Tom Pennance1,2, Amina Amadou Hamidou3, Bonnie Lee Webster1, Rabiou Labbo3,4, Aidan Mark Emery1, Amadou Djirmay Garba3,5 and David Rollinson1 Abstract Background: Sound knowledge of the abundance and distribution of intermediate host snails is key to understand- ing schistosomiasis transmission and to inform efective interventions in endemic areas. Methods: A longitudinal feld survey of freshwater snails of biomedical importance was undertaken in the Niger River Valley (NRV) between July 2011 and January 2016, targeting Bulinus spp. and Biomphalaria pfeiferi (intermedi- ate hosts of Schistosoma spp.), and Radix natalensis (intermediate host of Fasciola spp.). Monthly snail collections were carried out in 92 sites, near 20 localities endemic for S. haematobium. All bulinids and Bi. pfeiferi were inspected for infection with Schistosoma spp., and R. natalensis for infection with Fasciola spp. Results: Bulinus truncatus was the most abundant species found, followed by Bulinus forskalii, R. natalensis and Bi. pfeiferi. High abundance was associated with irrigation canals for all species with highest numbers of Bulinus spp. and R. natalensis. Seasonality in abundance was statistically signifcant in all species, with greater numbers associated with dry season months in the frst half of the year. Both B. truncatus and R. natalensis showed a negative association with some wet season months, particularly August. -

Assessing the Diversity and Distribution of Potential Intermediate Hosts Snails for Urogenital Schistosomiasis: Bulinus Spp

Chibwana et al. Parasites Vectors (2020) 13:418 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04281-1 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access Assessing the diversity and distribution of potential intermediate hosts snails for urogenital schistosomiasis: Bulinus spp. (Gastropoda: Planorbidae) of Lake Victoria Fred D. Chibwana1,2*, Immaculate Tumwebaze1, Anna Mahulu1, Arthur F. Sands1 and Christian Albrecht1 Abstract Background: The Lake Victoria basin is one of the most persistent hotspots of schistosomiasis in Africa, the intesti- nal form of the disease being studied more often than the urogenital form. Most schistosomiasis studies have been directed to Schistosoma mansoni and their corresponding intermediate snail hosts of the genus Biomphalaria, while neglecting S. haematobium and their intermediate snail hosts of the genus Bulinus. In the present study, we used DNA sequences from part of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene and the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) region to investigate Bulinus populations obtained from a longitudinal survey in Lake Victoria and neighbouring systems during 2010–2019. Methods: Sequences were obtained to (i) determine specimen identities, diversity and phylogenetic positions, (ii) reconstruct phylogeographical afnities, and (iii) determine the population structure to discuss the results and their implications for the transmission and epidemiology of urogenital schistosomiasis in Lake Victoria. Results: Phylogenies, species delimitation methods (SDMs) and statistical parsimony networks revealed the presence of two main groups of Bulinus species occurring in Lake Victoria; B. truncatus/B. tropicus complex with three species (B. truncatus, B. tropicus and Bulinus sp. 1), dominating the lake proper, and a B. africanus group, prevalent in banks and marshes. -

The Golden Apple Snail: Pomacea Species Including Pomacea Canaliculata (Lamarck, 1822) (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae)

The Golden Apple Snail: Pomacea species including Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck, 1822) (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae) DIAGNOSTIC STANDARD Prepared by Robert H. Cowie Center for Conservation Research and Training, University of Hawaii, 3050 Maile Way, Gilmore 408, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA Phone ++1 808 956 4909, fax ++1 808.956 2647, e-mail [email protected] 1. PREFATORY COMMENTS The term ‘apple snail’ refers to species of the freshwater snail family Ampullariidae primarily in the genera Pila, which is native to Asia and Africa, and Pomacea, which is native to the New World. They are so called because the shells of many species in these two genera are often large and round and sometimes greenish in colour. The term ‘golden apple snail’ is applied primarily in south-east Asia to species of Pomacea that have been introduced from South America; ‘golden’ either because of the colour of their shells, which is sometimes a bright orange-yellow, or because they were seen as an opportunity for major financial success when they were first introduced. ‘Golden apple snail’ does not refer to a single species. The most widely introduced species of Pomacea in south-east Asia appears to be Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck, 1822) but at least one other species has also been introduced and is generally confused with P. canaliculata. At this time, even mollusc experts are not able to distinguish the species readily or to provide reliable scientific names for them. This confusion results from the inadequate state of the systematics of the species in their native South America, caused by the great intra-specific morphological variation that exists throughout the wide distributions of the species. -

Phylogeny of Seven Bulinus Species Originating from Endemic Areas In

Zein-Eddine et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2014) 14:271 DOI 10.1186/s12862-014-0271-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Phylogeny of seven Bulinus species originating from endemic areas in three African countries, in relation to the human blood fluke Schistosoma haematobium Rima Zein-Eddine1*, Félicité Flore Djuikwo-Teukeng1,2, Mustafa Al-Jawhari3, Bruno Senghor4, Tine Huyse5 and Gilles Dreyfuss1 Abstract Background: Snails species belonging to the genus Bulinus (Planorbidae) serve as intermediate host for flukes belonging to the genus Schistosoma (Digenea, Platyhelminthes). Despite its importance in the transmission of these parasites, the evolutionary history of this genus is still obscure. In the present study, we used the partial mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (cox1) gene, and the nuclear ribosomal ITS, 18S and 28S genes to investigate the haplotype diversity and phylogeny of seven Bulinus species originating from three endemic countries in Africa (Cameroon, Senegal and Egypt). Results: The cox1 region showed much more variation than the ribosomal markers within Bulinus sequences. High levels of genetic diversity were detected at all loci in the seven studied species, with clear segregation between individuals and appearance of different haplotypes, even within same species from the same locality. Sequences clustered into two lineages; (A) groups Bulinus truncatus, B. tropicus, B. globosus and B. umbilicatus; while (B) groups B. forskalii, B. senegalensis and B. camerunensis. Interesting patterns emerge regarding schistosome susceptibility: Bulinus species with lower genetic diversity are predicted to have higher infection prevalence than those with greater diversity in host susceptibility. Conclusion: The results reported in this study are very important since a detailed understanding of the population genetic structure of Bulinus is essential to understand the epidemiology of many schistosome parasites. -

Schistosomiasis: Diploma Program

MODULE \ Schistosomiasis Diploma Program For the Ethiopian Health Center Team Laikemariam Kassa, Anteneh Omer, Wutet Tafesse, Tadele Taye, Fekadu Kebebew, Abdi Beker Haramaya University In collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education 2005 Funded under USAID Cooperative Agreement No. 663-A-00-00-0358-00. Produced in collaboration with the Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, The Carter Center, the Ethiopia Ministry of Health, and the Ethiopia Ministry of Education. Important Guidelines for Printing and Photocopying Limited permission is granted free of charge to print or photocopy all pages of this publication for educational, not-for-profit use by health care workers, students or faculty. All copies must retain all author credits and copyright notices included in the original document. Under no circumstances is it permissible to sell or distribute on a commercial basis, or to claim authorship of, copies of material reproduced from this publication. ©2005 by Laikemariam Kassa, Anteneh Omer, Wutet Tafesse, Tadele Taye, Fekadu Kebebew, Abdi Beker All rights reserved. Except as expressly provided above, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the author or authors. This material is intended for educational use only by practicing health care workers or students and faculty in a health care field. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The authors are grateful to The Carter Center and its staffs for the financial, material, and moral support without which it would have been impossible to develop this module. -

Article-P850.Pdf

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 96(4), 2017, pp. 850–855 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0614 Copyright © 2017 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Divergent Effects of Schistosoma haematobium Exposure on Intermediate-Host Snail Species Bulinus nasutus and Bulinus globosus from Coastal Kenya H. Curtis Kariuki,1 Julianne A. Ivy,2 Eric M. Muchiri,1 Laura J. Sutherland,2 and Charles H. King2* 1Division of Vector Borne Diseases, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya; 2Center for Global Health and Diseases, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio Abstract. Schistosoma haematobium infection causes urogenital schistosomiasis, a chronic inflammatory disease that is highly prevalent in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Bulinid snails are the obligate intermediate hosts in the transmission of this parasite. In the present study, Bulinus globosus and Bulinus nasutus snails from coastal Kenya were raised in the laboratory and exposed to miracidia derived from sympatric S. haematobium specimens to assess the species-specific impact of parasite contact and infection. The snails’ subsequent patterns of survival, cercarial shedding, and reproduction were monitored for up to 3 months postexposure. Schistosoma haematobium exposure significantly decreased the survival of B. globosus, but not of B. nasutus. Although both species were capable of transmitting S. haematobium,theB. globosus study population had a greater cumulative incidence of cercarial shedders and a higher average number of cercariae shed per snail than did the B. nasutus population. The effects of prior parasite exposure on snail reproduction were different between the two species. These included more numerous production of egg masses by exposed B. -

Studies on the Morphology and Compatibility Between Schistosoma Hæmatobium and the Bulinus Sp

African Journal of Biotechnology Vol. 4 (9), pp. 1010-1016, September 2005 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB ISSN 1684–5315 © 2005 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Studies on the morphology and compatibility between Schistosoma hæmatobium and the Bulinus sp. complex (gastropoda: planorbidae) in Cameroon Mimpfoundi Remy* and Ndassa Arouna General Biology Laboratory Faculty of Science, P.O Box 812 Yaoundé I Cameroon. Accepted March, 2005 A description is given of the morphological variation of the shell, the radula features and the copulatory organ of Bulinus sp. (2n=36) from four populations in the western Cameroon crater lakes. To assess the role of diploid snails belonging to the Bulinus natalensis/tropicus complex in the transmission of urinary schistosomiasis in Cameroon, the relation between Bulinus sp. (from four Cameroon crater lakes) and Schistosoma haematobium (from three transmission foci) were studied. Bulinus sp. in the present study refers to the diploid snail (2n=36) tentatively identified as Bulinus natalensis or as Bulinus tropicus in the Cameroon crater lakes. The percentage infection of snails challenged ranged from 03.33 to 06.00% for Nchout Monoun population and from 01.85 to 04.76% for Monoun Ngouondam population. No progeny from Petponoun-East and Petponoun-West were experimentally successfully infected with S. haematobium. All the 351 snails dissected were euphallic. Previous malacological surveys revealed the absence of Bulinus sp. naturally infected with human schistosomes. These results suggested that Bulinus sp. was not susceptible to infection with S. haematobium in the Cameroon Western highland crater lakes. These observations justify the absence of transmission foci (for urinary schistosomiasis) in this area. -

Bulinus Senegalensis and Bulinus Umbilicatus Snail Infestations by the Schistosoma Haematobium Group in Niakhar, Senegal

pathogens Article Bulinus senegalensis and Bulinus umbilicatus Snail Infestations by the Schistosoma haematobium Group in Niakhar, Senegal Papa Mouhamadou Gaye 1,2,3,4 , Souleymane Doucoure 2, Bruno Senghor 2 , Babacar Faye 5, Ndiaw Goumballa 1,2,3, Mbacké Sembène 4, Coralie L’Ollivier 1,3 , Philippe Parola 1,3, Stéphane Ranque 1,3 , Doudou Sow 2,5,6,* and Cheikh Sokhna 1,2,3 1 Aix-Marseille Université, IRD, AP-HM, SSA, VITROME, 13005 Marseille, France; [email protected] (P.M.G.); [email protected] (N.G.); [email protected] (C.L.); [email protected] (P.P.); [email protected] (S.R.); [email protected] (C.S.) 2 VITROME, Campus International IRD-UCAD de l’IRD, 1386 Dakar, Senegal; [email protected] (S.D.); [email protected] (B.S.) 3 Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire (IHU)-Méditerranée Infection de Marseille, 13005 Marseille, France 4 Département Biologie Animale, Faculté des Sciences et Technique, UCAD de Dakar, 5005 Dakar, Senegal; [email protected] 5 Department of Parasitology-Mycology, Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Odontology, University Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar, 5005 Dakar, Senegal; [email protected] 6 Department of Parasitology-Mycology, UFR Sciences de la Santé, Université Gaston Berger, 234 Saint-Louis, Senegal * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Thorough knowledge of the dynamics of Bulinus spp. infestation could help to control the Citation: Gaye, P.M.; Doucoure, S.; spread of schistosomiasis. This study describes the spatio-temporal dynamics of B. senegalensis and Senghor, B.; Faye, B.; Goumballa, N.; B. umbilicatus infestation by the Schistosoma haematobium group of blood flukes in Niakhar, Senegal. -

Urogenital Schistosomiasis and Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis (STH)

Campbell et al. Infectious Diseases of Poverty (2017) 6:49 DOI 10.1186/s40249-017-0264-8 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Urogenital schistosomiasis and soil- transmitted helminthiasis (STH) in Cameroon: An epidemiological update at Barombi Mbo and Barombi Kotto crater lakes assessing prospects for intensified control interventions Suzy J. Campbell1, J. Russell Stothard1*, Faye O’Halloran1, Deborah Sankey1, Timothy Durant1, Dieudonné Eloundou Ombede2, Gwladys Djomkam Chuinteu2, Bonnie L. Webster3,6, Lucas Cunningham1, E. James LaCourse1 and Louis-Albert Tchuem-Tchuenté2,4,5 Abstract Background: The crater lakes of Barombi Mbo and Barombi Kotto are well-known transmission foci of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis having had several important control initiatives previously. To collect contemporary epidemiological information, a cross-sectional survey was undertaken inclusive of: signs and symptoms of disease, individual treatment histories, local water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH)-related factors and malacological surveillance, with molecular characterisation of specimens. Methods: At each lake, a community cross-sectional survey was undertaken using a combination of stool and urine parasitological sampling, and interview with pro-forma questionnaires. A total of 338 children and adults participated. Material from snail and parasite species were characterised by DNA methods. Results: Egg-patent prevalence of urogenital schistosomiasis was 8.7% at Barombi Mbo (all light-intensity infections) and 40.1% at Barombi Kotto (21.2% heavy-intensity infections). Intestinal schistosomiasis was absent. At Barombi Kotto, significantly more women reported signs and symptoms associated with female genital schistosomiasis. While there had been extensive recent improvement in WASH-related infrastructure at Barombi Mbo, water contact risk scores were higher among schistosomiasis-infected participants (P < 0.001) and at Barombi Kotto in general (P < 0.001). -

Schistosomiasis Collection at NHM (SCAN) Aidan M Emery*, Fiona E Allan, Muriel E Rabone and David Rollinson

Emery et al. Parasites & Vectors 2012, 5:185 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/5/1/185 SHORT REPORT Open Access Schistosomiasis collection at NHM (SCAN) Aidan M Emery*, Fiona E Allan, Muriel E Rabone and David Rollinson Abstract Background: The Natural History Museum (NHM) is developing a repository for schistosomiasis-related material, the Schistosomiasis Collection at NHM (SCAN) as part of its existing Wolfson Wellcome Biomedical Laboratory (WWBL). This is timely because a major research and evaluation effort to understand control and move towards elimination of schistosomiasis in Africa has been initiated by the Schistosomiasis Consortium for Operational Research and Evaluation (SCORE), resulting in the collection of many important biological samples, including larval schistosomes and snails. SCAN will collaborate with a number of research groups and control teams and the repository will acquire samples relevant to both immediate and future research interest. The samples collected through ongoing research and field activities, WWBL’s existing collections, and other acquisitions will be maintained over the long term and made available to the global research community for approved research purposes. Goals include: • Consolidation of the existing NHM schistosome and snail collections and transfer of specimens into suitable long- term storage systems for DNA retrieval, • Long-term and stable storage of specimens collected as part of on going field programmes initially in Africa especially relating to the SCORE research programmes, • Provision of access to snail and schistosome collections for approved research activities. Keywords: Schistosoma, Biomphalaria, Bulinus, Biobank, Collection, Museum Findings SCAN (Schistosomiasis Collection at NHM), is to cap- Background ture material now for future comparative studies. -

Potential of Lanistes Varicus in Limiting the Population of Bulinus Truncatus Francis Anto1* and Langbong Bimi2

Anto and Bimi BMC Res Notes (2017) 10:509 DOI 10.1186/s13104-017-2837-9 BMC Research Notes RESEARCH NOTE Open Access Potential of Lanistes varicus in limiting the population of Bulinus truncatus Francis Anto1* and Langbong Bimi2 Abstract Objective: To determine the ability of the Ampullariid, Lanistes varicus to prey on egg masses and juveniles of Bulinus truncatus snails, an intermediate host of urogenital schistosomiasis in West Africa. Results: Lanistes varicus was found to feed voraciously on egg masses and juveniles of Bulinus truncatus, consuming all egg masses (20 –25) exposed to it within 24 h. Also, 95–100% of 1–2 days old B. truncatus snails exposed to a single L. varicus snail was consumed within 4 days. The presence of L. varicus snails greatly increased mortality in B. truncatus with mortality increasing with increase in the number of L. varicus snails in the mixture of the two snail species. The current study has demonstrated under laboratory conditions that the Ghanaian strain of L. varicus has the potential of limiting the population of B. truncatus snails, and contribute to the control of urogenital schistosomiasis in West Africa. Keywords: Lanistes varicus, Bulinus truncatus, Schistosoma haematobium, Tono irrigation system, Biological control Introduction potential to control the intermediate host snail of intes- Human schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia, is a tinal schistosomiasis—Biomphalaria pfeiferi [4] which is complex of acute and chronic parasitic infections caused of a more global interest. Te current study was a follow- by mammalian blood fukes of the genus Schistosoma. up to investigate whether L. varicus snail has any biologi- Control of the disease currently focuses on reducing cal control impact on B. -

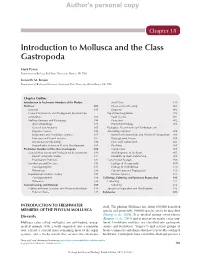

Introduction to Mollusca and the Class Gastropoda

Author's personal copy Chapter 18 Introduction to Mollusca and the Class Gastropoda Mark Pyron Department of Biology, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, USA Kenneth M. Brown Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA Chapter Outline Introduction to Freshwater Members of the Phylum Snail Diets 399 Mollusca 383 Effects of Snail Feeding 401 Diversity 383 Dispersal 402 General Systematics and Phylogenetic Relationships Population Regulation 402 of Mollusca 384 Food Quality 402 Mollusc Anatomy and Physiology 384 Parasitism 402 Shell Morphology 384 Production Ecology 403 General Soft Anatomy 385 Ecological Determinants of Distribution and Digestive System 386 Assemblage Structure 404 Respiratory and Circulatory Systems 387 Watershed Connections and Chemical Composition 404 Excretory and Neural Systems 387 Biogeographic Factors 404 Environmental Physiology 388 Flow and Hydroperiod 405 Reproductive System and Larval Development 388 Predation 405 Freshwater Members of the Class Gastropoda 388 Competition 405 General Systematics and Phylogenetic Relationships 389 Snail Response to Predators 405 Recent Systematic Studies 391 Flexibility in Shell Architecture 408 Evolutionary Pathways 392 Conservation Ecology 408 Distribution and Diversity 392 Ecology of Pleuroceridae 409 Caenogastropods 393 Ecology of Hydrobiidae 410 Pulmonates 396 Conservation and Propagation 410 Reproduction and Life History 397 Invasive Species 411 Caenogastropoda 398 Collecting, Culturing, and Specimen Preparation 412 Pulmonata 398 Collecting 412 General Ecology and Behavior 399 Culturing 413 Habitat and Food Selection and Effects on Producers 399 Specimen Preparation and Identification 413 Habitat Choice 399 References 413 INTRODUCTION TO FRESHWATER shell. The phylum Mollusca has about 100,000 described MEMBERS OF THE PHYLUM MOLLUSCA species and potentially 100,000 species yet to be described (Strong et al., 2008).