SOME REFLECTIONS on SOLA FIDE . . . Thomas R. Schreiner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Future of Evangelicals in Mission: Will We Regain the Kingdom Vision of Our Forefathers in the Faith? Ralph D

1 From (Frontiers in Mission, 327-43) The Future of Evangelicals in Mission: Will We Regain the Kingdom Vision of Our Forefathers in the Faith? Ralph D. Winter, W1489C.14, 3/9/08 A flood of light on the future of the Evangelical movement and its mission vision can be deduced by looking closely at its roots. Evangelicals happen to have a rich heritage of faith and works, extensively forgotten, that can once again inspire and instruct us as we seek to bring a complete gospel to every tribe and tongue. Evangelicals? Who Are They? The word evangelical in the Catholic tradition refers to those people who take the four Evangelical gospels very seriously—specifically, members of Catholic orders. Later, in the Protestant tradition, the word evangelical came to refer to a political party where the evangelici, adhering to the authority of the Bible, were opposed to the pontifici who supported the authority of the Pope. However, at the time of the Reformation other things were going on besides tension between two parties. There were the Anabaptists and later on Pietists and still later a still different kind of “Evangelical,” namely Quakers, and eventually, the Methodists, who became a global force. As a broad generalization, all of these additional “third force” movements came to understand the word Evangelical to mean more than correct belief. The word began to refer to those individuals who had had a personal “evangelical experience,” by which was meant something real had happened in a person’s heart and life not just purely mental assent to a prescribed intellectual creed. -

Law and Gospel Article

RENDER UNTO RAWLS: LAW, GOSPEL, AND THE EVANGELICAL FALLACY Wayne R. Barnes∗ I. INTRODUCTION Many explicitly Christian voices inject themselves frequently and regularly into the current public policy and political discourse. Though not all, many of these Christian arguments proceed in something like the following manner. X is condemned (or required) by God, as revealed in the Bible. Therefore, the explicitly-required “Christian position” on X is for the law to prohibit or limit the activity (or require it), in accordance with the advocate’s interpretation of biblical ethical standards. To be clear, I mean to discuss only those scenarios where a Christian publicly identifies a position as being mandated by Christian morality or values --- i.e., where the public is given a message that some law or public policy is needed in order to comply with the Christian scriptures or God’s will. That is, in short, this article is about explicit political communications to the public in overt religious language of what Christianity supposedly requires for law and policy. As will be seen, these voices come quite famously from the Christian Religious Right, but they come from the Religious Left as well. Political philosophers (most famously John Rawls) have posited that pluralism and principles of liberal democracy strongly counsel against resort to such religious views in support of or against any law or public policy.1 That is, in opposition to this overt religious advocacy in the political realm (though, it should be noted, not necessarily taking a substantive position on the issues, per se) is the position of Rawlsian political liberalism, which states generally that, all things being equal, such inaccessible religious arguments should not be made, but rather arguments should only be made by resort to “public reason” which all find to be accessible.2 Christian political voices counter that this results in an intolerable stifling of their voice, of requiring that they “bracket” ∗ Professor, Texas Wesleyan University School of Law. -

Justification: Law, Gospel and Assurance of Salvation

JUSTIFICATION: LAW, GOSPEL AND ASSURANCE OF SALVATION In paragraphs 31-33, the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification (JDDJ) considers the relationship of the Gospel to the Law of Moses. In keeping with the Christian teaching since Apostolic times, both Catholics and Lutherans affirm that “Christ has fulfilled the law and by his death and resurrection has overcome it as a way to salvation.” [JDDJ, #31] We are justified by faith in the Gospel, not by following the commands of the Old Law. Does this mean that the Old Testament commandments are irrelevant and we can ignore them? Not at all. Although we receive our salvation through Jesus Christ and not through the law, God’s commandments still offer us guidance for proper behavior and our failures to follow them can be accusations of our sinfulness. It is not enough for us to be justified, we must also live as the justified. By his teaching and example, Christ has shown us God’s will, which is the standard for our conduct. Christ is not a lawgiver like Moses, but is the Father’s perfect revelation of himself. Christ did not give us a listing of commands to follow, but rather showed us in his person how to live as children of God. Even as we recognize our sinfulness when we violate the commandments, we also realize that it is only the mercy of God in Christ that justifies us, not the remedies or practices of the law. “The law as a way to salvation has been fulfilled and overcome through the gospel.” [JDDC, #31] So when we repent of sin, we do not rely on our own penitential actions for our redemption, but rather put our faith in the Gospel and place ourselves at God’s mercy in Christ, our only source of salvation. -

Sola Fide and Sola Gratia in Early Christianity

Salvation sola fide and sola gratia in early Christianity Published in: P.N. Holtrop, F. De Lange, R. Roukema (eds), Passion of Protestants, Kampen 2004, 27-48 Riemer Roukema Martin Luther‟s passion was to proclaim his discovery that man is justified by faith in Christ. This meant to him that, in man‟s relationship with God, he does not have to correspond to God‟s „righteousness‟ by his own „works‟ or efforts, but that God freely bestows the righteousness of Christ on everyone who believes in Christ as Saviour.1 Luther even intro- duced his discovery into his translation of Rom. 3:28. Whereas Paul wrote there that „man is justified by faith apart from works of the law‟, Luther translated that „man is justified without works of the law, only by faith‟.2 Although this translation was fiercely criticized, he vigorously defended it, saying that a version including „only‟ made up a more natural German sentence than without this adverb. Moreover, he referred to Ambrose and Augustine who said before him that faith alone makes one righteous.3 In Latin, „only by faith‟ is sola fide; combined with sola gratia, „only by grace‟, these words became important slogans of Lutheran and Calvinist Protestantism. For sola gratia, one may refer to Rom. 3:24, „justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption which is in Christ Jesus‟ (RSV), and to Eph. 2:8-9a, „For by grace you have been saved through faith; and this is not your own doing, it is the gift of God, not because of works‟ (RSV). -

The Five Solas of the Reformation

The Five Solas of the Reformation Contents Background ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Sola Gratia ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Indulgences .................................................................................................................................. 6 Definition of Grace ...................................................................................................................... 7 Grace Alone ................................................................................................................................. 9 Grace is Part of the Character of God ...................................................................................... 9 Grace is Clearly Displayed by the Cross of Jesus .................................................................. 11 Grace is Expressed in Different Ways ................................................................................... 12 Grace is Pure .......................................................................................................................... 14 Grace is Sovereign ................................................................................................................. 14 Grace in Relation to the Law ................................................................................................. 16 Grace is Given -

Turning Point: Luther at the Diet of Worms (1521)

Turning Point: Luther at the Diet of Worms (1521) Mark Noll, Turning Points, ch. 7 Key texts to start with: The Freedom of a Christian, On the Bondage of the Will, The Babylonian Captivity of the Church, The 95 Theses. Augsburg Confession of the Lutheran churches (1530). Luther on reading and teaching the Gospel narratives. Luther's amazing sermon on John 1:29. Luther's blistering commentary on Galatians. Guys who blog quite a bit on Luther - Ron Frost, Peter Mead, Glen Scrivener. Carl Trueman on Luther at the Clarus Conference 2005 - audio. Martin Luther in 30 minutes from MTC. A Mighty Fortress is Our God: The Story of Martin Luther - available at iServe Africa bookstore Graham Tomlin, Luther and his World – available in the iServe Africa library Michael Reeves, Unquenchable Flame / On Giant’s Shoulders Some of the key issues: Authority of Church versus authority of Word – “my conscience is captive to the Word of God” Against Papacy that Luther saw to be slamming the door to the kingdom in people’s faces, not going in and preventing others from entering Sacraments reduced to Baptism and Lord’s Supper (versus 7 catholic sacraments) Luther’s ‘theology of the Cross’ (from 1517 onwards) - increasingly seeing that the will is bound, can do no good of ourselves (and if we think that we can, that is evil); it is in powerlessness that there is power. This was an extension of Augustinianism that the church could no longer contain. Summary of Alister McGrath’s Luther’s Theology of the Cross, 1985 McGrath starts by placing Luther is his setting as a late medieval theologian of the via moderna. -

A Theology of Good Works: the Apostle Paul's Concept of Good Works Within the Context Of

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY A THEOLOGY OF GOOD WORKS: THE APOSTLE PAUL’S CONCEPT OF GOOD WORKS WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF SECOND TEMPLE JUDAISM PRESENTED AT THE FIRST ANNUAL EVERYDAY THEOLOGY CONFERENCE MARCH 20, 2015 BY DR. MARTIN E. SHELDON A THEOLOGY OF GOOD WORKS: THE APOSTLE PAUL’S CONCEPT OF GOOD WORKS WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF SECOND TEMPLE JUDAISM Introduction The apostle Paul lived and ministered within the historical context of Second Temple Judaism.1 Following just over three decades of adherence to and immersion in Pharisaic Judaism, Saul of Tarsus converted to Jesus Christ and in consequence, conducted several missionary journeys proclaiming the gospel of Christ and writing letters to the newly established churches. While the Hebrew Scriptures provided the theological foundation for the apostle Paul’s teaching, his concept of good works was forged within the historical context of Second Temple Judaism. Inasmuch as this is the case, it is essential to explore the concept of good works within the OT and Second Temple Literature in order to accurately assess the apostle Paul’s theology of good works. This inquiry will assess Paul’s theology of good works in comparison to the Old Testament (OT) Pseudepigrapha, OT Apocrypha, the Dead Sea Scrolls, Josephus, and Philo in order to determine how Paul’s concept compares to that of the relevant Second Temple literature. Second Temple literature emphasizes the necessity of performing good works such as virtuous living and morality, alms-giving, prayer, and fasting; and exemplifies God’s people as those who adhere to the Mosaic Law. -

C:\WW Manuscripts\Back Issues\11-3 Lutheranism\11

Word & World 11/3 (1991) Copyright © 1991 by Word & World, Luther Seminary, St. Paul, MN. All rights reserved. page 276 A North American Perspective TODD W. NICHOL Luther Northwestern Theological Seminary, Saint Paul, Minnesota Thirty years ago, historian Winthrop Hudson called Lutheranism the last, best hope of Protestantism in the United States. Insularity, Hudson said in his widely read study American Protestantism, had protected Lutherans from the theological disintegration and lack of connection to historical tradition he thought characteristic of most other American Protestants. As Hudson saw it, a history of more or less intentional parochialism had given Lutherans specific advantages that could put them in the vanguard of a Protestant renewal in the United States: the effect of impending mergers, rising membership, a confessional tradition, liturgical practice, and a sense of community based in part on sociological factors.1 A generation later, however, it appears that Hudson missed his guess. In the last three decades, questions regarding merger and membership, theology and worship, and the contours of community have troubled and sometimes divided American Lutherans. That these things matter to some Lutherans is, of course, evidence that Winthrop Hudson’s optimistic assessment of Lutheranism in the United States was not entirely without basis. Yet few knowledgeable Lutherans in 1991 would be prepared to claim that their churches have taken the leading role in a renewal of Protestantism in North America or that they are now in a position to do so. American Lutheranism is now more difficult to assess than even so distinguished an historian of American religion as Winthrop Hudson was able to predict thirty years ago. -

Luther and the Doctrine of Justification

B CONCORDIA e THEOLOGICAL m-Lx 3% QUARTERLY .- 0 C-% Volume 48, Number I =I si 5"- - - 0 : --I 1 JANUARY 1984 : ' v) Luther and the Doctrine of Justification .... Robert D. Preus 1 Luther and Music .......................Daniel Reuning 17 Luther's Impact on the Universities - and the Reverse. ...................James M. Kittelson 23 Luther Research in America and Japan .............. Lewis W. Spitz and Morimichi Watanabe 39 The Import of the Two-Gospel Hypothesis. .......................William R. Farmer 55 Linguistic Nonsense about Faith .........Theodore Mueller 61 For Freedom Christ Has Set Us Free ...........................Luther and Arlene Strasen 67 Theological Observer ................................. 69 Book Reviews ....................................... 75 Books Received. ..................................... 89 CONCORD lA TH EOLOGXAL SEMINAR1 LILRARY Luther and the Doctrine of Justification Robert D. Preus In this article I will address myself to the centrality of the doctrine of justification in Luther's theology and how it worked its way out in Luther's hermeneutics and theological enterprise as a whole. Stress has always been placed by Lutheran theologians and historians on the importance of the doctrine of justification for Luther in his search for a gracious God and in his theological writings. May I merely cite a small representative number of statements from Luther on the centrality, importance, and usefulness of the article of justification. If we lose the doctrine of justification, we lose simply everything. Hence the most necessary and important thing is that we teach and repeat this doctrine daily, as Moses says about his Law (Deut. 6:7). For it cannot be grasped or held enough or too much. In fact, though we may urge and inculcate it vigorously, no one grasps it perfectly or believes it with all his heart. -

Sola Fide the Relevance of Remembering the Reformation

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary ConcordiaPages Resources for Ministry 1-1-2018 Sola Fide The Relevance of Remembering the Reformation Erik Herrmann Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/concordiapages Part of the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Herrmann, Erik, "Sola Fide The Relevance of Remembering the Reformation" (2018). ConcordiaPages. 6. https://scholar.csl.edu/concordiapages/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Resources for Ministry at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in ConcordiaPages by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOLA FIDE THE RELEVANCE OF REMEMBERING THE REFORMATION ERIK HERRMANN pages SOLA FIDE THE RELEVANCE OF REMEMBERING THE REFORMATION ERIK HERRMANN About the Author Erik Herrmann r. Erik Herrmann is associate professor of historical theology, chairman of the Department of Historical Theology, director of Concordia Theology, and director of the Center for Reformation Research at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis. DHerrmann joined the faculty of Concordia Seminary in 2005 after serving as an assistant pastor at Timothy Lutheran Church in St. Louis. He received his Ph.D. (2005) and Master of Divinity (2000) from Concordia Seminary. His earned his bachelor’s degree (1995) from Concordia University Wisconsin. His areas of interest and expertise include the history of biblical interpretation, with a particular focus on Martin Luther and the Reformation period; history of Medieval and Reformation/early modern Europe; 20th–century interpretations of Martin Luther and his theology; and the history of American Lutheranism. -

Reformed Tradition

THE ReformedEXPLORING THE FOUNDATIONS Tradition: OF FAITH Before You Begin This will be a brief overview of the stream of Christianity known as the Reformed tradition. The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, the Reformed Church in America, the United Church of Christ, and the Christian Reformed Church are among those considered to be churches in the Reformed tradition. Readers who are not Presbyterian may find this topic to be “too Presbyterian.” We encourage you to find out more about your own faith tradition. Background Information The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) is part of the Reformed tradition, which, like most Christian traditions, is ancient. It began at the time of Abraham and Sarah and was Jewish for about two thousand years before moving into the formation of the Christian church. As Christianity grew and evolved, two distinct expressions of Christianity emerged, and the Eastern Orthodox expression officially split with the Roman Catholic expression in the 11th century. Those of the Reformed tradition diverged from the Roman Catholic branch at the time of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. Martin Luther of Germany precipitated the Protestant Reformation in 1517. Soon Huldrych Zwingli was leading the Reformation in Switzerland; there were important theological differences between Zwingli and Luther. As the Reformation progressed, the term “Reformed” became attached to the Swiss Reformation because of its insistence on References Refer to “Small Groups 101” in The Creating WomanSpace section for tips on leading a small group. Refer to the “Faith in Action” sections of Remembering Sacredness for tips on incorporating spiritual practices into your group or individual work with this topic. -

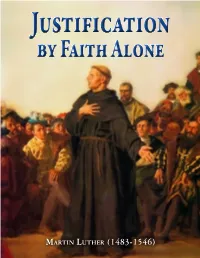

Justification by Faith Alone

Justification by Faith Alone MARTIN LUTHER (1483-1546) JUSTIFICATION BY FAITH ALONE Contents The Argument of Galatians 1. Righteousness by Faith ..................................................................................... 3 2. Condemnation by the Works of the Law ....................................................... 4 3. Teaching about Law and Grace ....................................................................... 5 4. Separating Law and Grace in Salvation .......................................................... 6 5. Proper Places of Works and Grace ................................................................. 7 Commentary on Galatians 2:16 1. The Works of the Law ..................................................................................... 8 2. The Divinity of the Popish Sophisters (commonly called Schoolmen) .......... 9 3. The True Way to Christianity ...................................................................... 11 4. Error of the Schoolmen: “Charity” as Merit ................................................. 12 5. Answer to the Schoolmen .............................................................................. 14 6. The True Rule of Christianity ....................................................................... 14 7. False Teachers ................................................................................................. 18 8. The Grace of God ........................................................................................... 18 9. Faith Alone .....................................................................................................