Efforts to Reduce the Impact of Generic Competition Could Have Legal Repercussions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top Twenty Pay-For-Delay Drugs: How Drug Industry Payoffs Delay Generics, Inflate Prices and Hurt Consumers

TOP TWENTY PAY-FOR-DELAY DRUGS: HOW DRUG INDUSTRY PAYOFFS DELAY GENERICS, INFLATE PRICES AND HURT CONSUMERS oo often, consumers are forced to shoulder a heavy financial burden, or even go without needed medicine, due to the high cost of brand-name drugs. Our research indicates that one significant cause is Tthe practice called “pay for delay,” which inflates the drug prices paid by tens of millions of Americans. In a pay-for-delay deal, a brand-name drug company pays off a would-be competitor to delay it from selling a generic version of the drug. Without any competition, the brand-name company can continue demanding high prices for its drug. This list of 20 drugs known to be impacted by pay-for-delay deals represents the tip of the iceberg. Annual reports by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) indicate that generic versions of as many as 142 brand-name drugs have been delayed by pay-for-delay arrangements between drug manufacturers since 2005.1 However, because the details of these deals rarely become public, consumers have largely been kept in the dark about the extent of the problem. Information about these twenty specific drugs affected by pay-for-delay deals has been made public thanks to legal challenges brought by the FTC, consumer class action lawsuits, research by legal experts, and public disclosures by drug makers. Key findings of our analysis of these 20 drugs impacted by pay-for-delay deals: . This practice has held back generic . These brand-name drugs cost medicines used by patients with a wide 10 times more than their generic range of serious or chronic conditions, equivalents, on average, and as much as ranging from cancer and heart disease, to 33 times more. -

Merck & Co., Inc

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on February 25, 2021 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D. C. 20549 _________________________________ FORM 10-K (MARK ONE) ☒ Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2020 OR ☐ Transition Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No. 1-6571 _________________________________ Merck & Co., Inc. 2000 Galloping Hill Road Kenilworth New Jersey 07033 (908) 740-4000 New Jersey 22-1918501 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation) (I.R.S Employer Identification No.) Securities Registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Trading Symbol(s) Name of Each Exchange on which Registered Common Stock ($0.50 par value) MRK New York Stock Exchange 1.125% Notes due 2021 MRK/21 New York Stock Exchange 0.500% Notes due 2024 MRK 24 New York Stock Exchange 1.875% Notes due 2026 MRK/26 New York Stock Exchange 2.500% Notes due 2034 MRK/34 New York Stock Exchange 1.375% Notes due 2036 MRK 36A New York Stock Exchange Number of shares of Common Stock ($0.50 par value) outstanding as of January 31, 2021: 2,530,315,668. Aggregate market value of Common Stock ($0.50 par value) held by non-affiliates on June 30, 2020 based on closing price on June 30, 2020: $195,461,000,000. Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

Cigna Standard 4-Tier Prescription Drug List

CIGNA STANDARD 4-TIER PRESCRIPTION DRUG LIST Coverage as of January 1, 2022 Offered by: Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company, Connecticut General Life Insurance Company, or their affiliates. 916152 j Standard 4-Tier O/I SRx 08/21 What’s inside? About this drug list 3 How to read this drug list 3 How to find your medication 5 Specialty medications 18 Medications that aren’t covered 25 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) 41 Exclusions and limitations for coverage 45 View the drug list online This document was last updated on 08/01/2021.* You can go online to see the current list of medications your plan covers. myCigna® App and myCigna.com. Click on the “Find Care & Costs” tab and select “Price a Medication.” Then type in your medication name to see how it’s covered. Cigna.com/PDL. Scroll down until you see a pdf of the Cigna Standard 4-Tier Prescription Drug List (all specialty medications covered on Tier 4). Questions? › myCigna.com: Click to chat Monday-Friday, 9:00 am-8:00 pm EST. › By phone: Call the toll-free number on your Cigna ID card. We’re here 24/7/365. * Drug list created: originally created 01/01/2004 Last updated: 08/01/2021, for changes Next planned update: 03/01/2022, for starting 01/01/2022 changes starting 07/01/2022 2 About this drug list This is a list of the most commonly prescribed medications covered on the Cigna Standard 4-Tier Prescription Drug List as of January 1, 2022.1,2 Medications are listed by the condition they treat, then listed alphabetically within tiers (or cost-share levels). -

Why Are Some Generic Drugs Skyrocketing in Price? Hearing Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions United States Sena

S. HRG. 113–859 WHY ARE SOME GENERIC DRUGS SKYROCKETING IN PRICE? HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PRIMARY HEALTH AND AGING OF THE COMMITTEE ON HEALTH, EDUCATION, LABOR, AND PENSIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON EXAMINING THE PRICING OF GENERIC DRUGS NOVEMBER 20, 2014 Printed for the use of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 24–459 PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:32 May 19, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\DOCS\24459.TXT DENISE HELPN-003 with DISTILLER COMMITTEE ON HEALTH, EDUCATION, LABOR, AND PENSIONS TOM HARKIN, Iowa, Chairman BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee PATTY MURRAY, Washington MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming BERNARD SANDERS (I), Vermont RICHARD BURR, North Carolina ROBERT P. CASEY, JR., Pennsylvania JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia KAY R. HAGAN, North Carolina RAND PAUL, Kentucky AL FRANKEN, Minnesota ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah MICHAEL F. BENNET, Colorado PAT ROBERTS, Kansas SHELDON WHITEHOUSE, Rhode Island LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin MARK KIRK, Illinois CHRISTOPHER S. MURPHY, Connecticut TIM SCOTT, South Carolina ELIZABETH WARREN, Massachusetts DEREK MILLER, Staff Director LAUREN MCFERRAN, Deputy Staff Director and Chief Counsel DAVID P. CLEARY, Republican Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON PRIMARY HEALTH AND AGING BERNARD SANDERS, Vermont, Chairman BARBARA A. -

Biologic, Biosimilar, Generic, and Brand

BIOSIMILARS Breaking Down the Differences Between Drug Types: Biologic, Biosimilar, Generic, and Brand-Name Drugs BIOSIMILARS This resource is designed to help you understand the differences between biosimilar, biologic, generic, and brand-name drugs so that you can be as informed as possible when it comes to treatment decisions. TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 · Introduction 3 · An Analogy: Cookies & Beer ABOUT FIGHT 4 · Background: Small and COLORECTAL CANCER Large Molecule Drugs We FIGHT to cure colorectal cancer and serve as relentless champions 7 · The Comparisons: of hope for all affected by this Brand-Name vs Generic disease through informed patient & Biologic vs Biosimilar support, impactful policy change, and breakthrough research endeavors. 13 · Making Your Decision 14 · More Information MEDICAL DISCLAIMER & Support The information and services provided by Fight Colorectal Cancer are for general informational purposes only and are not intended to be substitutes for professional medical advice, diagnoses, or treatment. If you are ill, or suspect that you are ill, see a doctor immediately. In an emergency, call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room. Fight Colorectal Cancer never recommends or endorses any specific physicians, products, or treatments for any condition. This mini magazine does not serve as an advertisement or endorsement for any products COVER: or sponsors mentioned. Patrick Moote Stage III survivor 1 • FightCRC.org • INTRODUCTION HILE AT THE PHARMACY OR IN YOUR DOCTOR’S OFFICE, you may have heard the terms “generic” and “brand-name.” WGeneric and brand-name drugs will remain staples in our healthcare system, and there’s a new kid on the block that you may soon encounter: biosimilars. -

Dr Reddy's Prescription to Stay Ahead of the Generic Pack

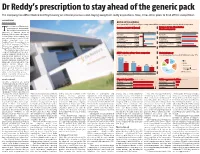

Dr Reddy’s prescription to stay ahead of the generic pack The company has differentiated itself by focusing on internal processes and staying away from costly acquisitions. Now, it has other plans to fend off the competition B DASARATH REDDY Hyderabad, 8 August BATTLE OF THE GENERICS As the patent cliff in the US levels off, generic drug makers will face increasing pressure to develop other kinds of products he revenues of Hyderabad- Revenues in 2011-12 (Actual) Revenue for top-three Indian based generic drug maker, Pharma companies T Dr Reddy's Laboratories, is expected to surpass those of ~ crore Revenue Net profit ~ crore 2012-13 2013-14* Ranbaxy Laboratories, the largest Ranbaxy 9,977 Ranbaxy 11,309 Indian generic drug company, and Laboratories* -2,900 Laboratories 12,615 now a subsidiary of Japan’s Daiichi Dr Reddy's 9,674 Dr Reddy's 11,286 Sankyo, sometime next year. Laboratories** 1,426 Laboratories 12,663 Barclays Equity Research projects 8,006 9,694 Dr Reddy’s revenues for FY14 at Sun Pharmaceutical Sun Pharmaceutical 2,587 11,472 ~12,663 crore, slightly higher than Industries** Industries Ranbaxy’s (at ~12,615 crore). *Calendar year 2011, **FY ended March 2012 *Estimates This would be big news for any company battling it out in a chal- ANDA* pipeline of top-three companies Global pharmacy lenging industry. However, the Approved Pending Share of consolidated revenues for Dr Reddy's in the year ‘11-12 generic-drug business is more than just that. It’s a fiercely com- 241 petitive business, driven by vol- umes and characterised by con- 148 148 stantly falling prices and, 101 therefore, steep margins. -

Dr Reddy's Laboratories Limited

DR REDDY'S LABORATORIES LIMITED Dr. Reddy's Laboratories is one of the largest research-driven pharmaceutical companies in India. Background Dr. Reddy's Laboratories is a vertically integrated, global pharmaceutical company with proven research capabilities.The second largest pharmaceutical company in India, Dr. Reddy's manufactures and markets a wide range of pharmaceutical products in India and overseas. Founded by Dr Anji Reddy, an entrepreneur- In the same year, Reddy US Therapeutics, a wholly- scientist, in 1984 at Hyderabad, the company owned subsidiary, was established at Atlanta, US to produces finished dosage forms,API, diagnostic kits, conduct target based drug discovery. critical care and biotechnology products.The company has over 190 finished dosages and 60 API In 2002, it made its first overseas acquisitions and currently in production. acquired two UK companies, namely BMS Laboratories Limited and Meridian Health Care In 1986, Dr. Reddy's entered the international (UK) Limited.The two firms produce oral solids markets with exports of Methyldopa. In 1987, it and liquids. In 2003, Dr Reddy's set up a joint obtained its first US FDA approval for Ibuprofen venture with Venturepharma in South Africa called API and started its formulations operations. In Dr Reddy's Laboratories (Proprietary) Ltd, South 1988, the company acquired Benzex Laboratories Africa to establish its presence in the Southern Pvt. Limited to expand its bulk actives business. Dr. Africa Development Community (SADEC) Reddy's raised a GDR issue of US$ 48 million in countries and sub-Saharan African territories.The 1994 and laid the foundation stone for a finished company has six US-FDA inspected plants. -

In Re: Clomipramine Cases

Case 2:17-cv-03813-CMR Document 1 Filed 08/15/17 Page 1 of 101 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA IN RE: GENERIC PHARMACEUTICALS MDL No. 2724 PRICING ANTITRUST LITIGATION No. 16-MD-2724 HON. CYNTHIA M. RUFE ______________________________________ IN RE: CLOMIPRAMINE CASES ______________________________________ THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ALL INDIRECT RESELLER PLAINTIFF 16-CM-27243 (IRP) ACTIONS CLASS ACTION JURY TRIAL DEMANDED INDIRECT RESELLER PLAINTIFFS’ CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Case 2:17-cv-03813-CMR Document 1 Filed 08/15/17 Page 2 of 101 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. NATURE OF THE ACTION ................................................................................................. 1 II. ONGOING INVESTIGATIONS ............................................................................................ 4 III. THE ROLE OF INDEPENDENT PHARMACIES ................................................................ 8 IV. JURISDICTION AND VENUE ............................................................................................. 9 V. PARTIES………………………………… .......................................................................... 10 Plaintiffs ................................................................................................................... 10 Defendants ............................................................................................................... 11 Co-conspirators ....................................................................................................... -

Biological Product Definitions

Biological Product Definitions What is a biological product? Reference Product Biological products are regulated by the Food and Drug A reference product is the single biological Administration (FDA) and are used to diagnose, prevent, product, already approved by FDA, against which a proposed biosimilar product is compared treat, and cure diseases and medical conditions. Biological products are a diverse category of products and are generally large, complex molecules. These products may Biosimilar Product be produced through biotechnology in a living system, A biosimilar is a biological product that is such as a microorganism, plant cell, or animal cell, highly similar and has no clinically meaningful and are often more difficult to characterize than small differences from an existing FDA-approved molecule drugs. There are many types of biological reference product products approved for use in the United States, including therapeutic proteins (such as filgrastim), monoclonal Interchangeable Product antibodies (such as adalimumab), and vaccines (such as An interchangeable product is a biosimilar those for influenza and tetanus). product that meets additional requirements The nature of biological products, including the inherent variations that can result from the manufacturing process, can present challenges in characterizing and What does it mean to be manufacturing these products that often do not exist in the development of small molecule drugs. Slight differences “highly similar”? between manufactured lots of the same biological product (i.e., acceptable within-product variations) are normal A manufacturer developing a proposed biosimilar and expected within the manufacturing process. As part demonstrates that its product is highly similar to of its review, FDA assesses the manufacturing process the reference product by extensively analyzing (i.e., and the manufacturer’s strategy to control within-product characterizing) the structure and function of both the variations. -

Draft Guidance on Testosterone

Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Draft Guidance on Testosterone This draft guidance, once finalized, will represent the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) current thinking on this topic. It does not create or confer any rights for or on any person and does not operate to bind FDA or the public. You can use an alternative approach if the approach satisfies the requirements of the applicable statutes and regulations. If you want to discuss an alternative approach, contact the Office of Generic Drugs. Active ingredient: Testosterone Form/Route: Gel/Transdermal Recommended studies: 1 study Type of study: Fasting Design: Single-dose, two-way crossover in vivo Strength: 1% (dose: 100 mg testosterone, i.e., contents of two 5 gm packets, each containing 50 mg testosterone in 5 gm gel) Subjects: Hypogonadal males with no other abnormalities Additional comments: 1. Because of significant safety concerns pertaining to the transfer of testosterone to others and the current inability of the Office of Generic Drugs (OGD) to adequately determine which new inactive ingredient(s) or change(s) in the formulation may significantly affect the safety of testosterone gel, the OGD plans to receive an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) for a generic version of Testosterone Transdermal Gel, 1% only if it has all of the same ingredients as the reference listed drug (RLD) and the concentration or amount of each inactive ingredient in the test product differs by no more than +/- 5% of the concentration or amount for the same ingredient in the RLD [the generic drug product is qualitatively (Q1) and quantitatively (Q2) the same, i.e., Q1/Q2, to the RLD]. -

Atorvastatin Calcium ANDA 76477

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Food and Drug Administration Rockville, MD 20857 ANDA 076477 Ranbaxy Inc. U.S. Agent for: Ranbaxy Laboratories Limited Attention: Scott D. Tomsky Senior Manager, Regulatory Affairs 600 College Road East Princeton, NJ 08540 Dear Sir: This is in reference to your abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) dated August 19, 2002, submitted pursuant to section 505(j) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (the Act), for Atorvastatin Calcium Tablets, 10 mg (base), 20 mg (base), 40 mg (base), and 80 mg (base). Reference is also made to your amendments dated December 4, and December 9, 2009; November 12, and November 16, 2010; and June 2, June 3, June 7, July 18, July 25, July 27, August 26, September 1, September 19, and October 5, 2011. We have completed the review of this ANDA and have concluded that adequate information has been presented to demonstrate that the drug is safe and effective for use as recommended in the submitted labeling. Accordingly the ANDA is approved, effective on the date of this letter. The Division of Bioequivalence has determined your Atorvastatin Calcium Tablets, 10 mg (base), 20 mg (base), 40 mg (base), and 80 mg (base), to be bioequivalent and, therefore, therapeutically equivalent to the reference listed drug (RLD), Lipitor Tablets, 10 mg (base), 20 mg (base), 40 mg (base), and 80 mg (base), respectively, of Pfizer, Inc. (Pfizer). Your dissolution testing should be incorporated into the stability and quality control program using the same method proposed in your ANDA. The RLD upon which you have based your ANDA, Pfizer’s Lipitor Tablets, is subject to periods of patent protection. -

Interceangeability of Low-Dose Oral Contraceptives Are Current

CONTRACEPTION INTERCEANGEABILITY OF LOW-DOSE ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES ARE CURRENT BIOEQUIVALENT TESTING MEASURES ADEQUATE TO ENSURE THERAPEUTIC EQUIVALENCY? Rudi Ansbacher, M.D., M.S. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology University of Michigan Medical Center Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-0718 Written while Scholar-in-Residence Health Policy International Princeton, New Jersey 08540 ABSTRACT Current Food and Drug Administration guidelines for assessing the differences in bioavailability between generic oral contraceptives and brand-name products are inadequate to ensure therapeutic equivalence. The guidelines do not take into account those women who may have blood levels of active ingredients well outside the range of acceptability. Due to the narrow therapeutic range of steroids, these women may become pregnant or experience an increased incidence of breakthrough bleeding. Furthermore, oral contraceptive packaging is unique to each manufacturer, and any change in brands (and therefore packaging) can easily negate the sequential administration of the appropriate tablet. These are among the reasons proposed for placing oral contraceptives in the critical drug category, in which generic substitution and interchangeability of products should not be allowed. Submitted for publication September 5, 1990 Accepted for publication December 18, 1990 FEBRUARY 1991 VOL. 43 NO. 2 139 CONTRACEPTION INTRODUCTION With the passage of the Drug Price Competitio and Patent Term Restoration Act (Waxman-Hatch Amendment) r in 1984 and the acceptance of drug bioavailability measures as a prediction of therapeutic equivalence, generic copies of brand-name medications became widely used. Since that time, a number of questions have arisen concerning the therapeutic efficacy of the generics, the reliability of the products that are interchanged, and whether such product interchange is appropriate for the patient.