Report Card 2018–19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rivers Monitoring and Evaluation Plan V1.0 2020

i Rivers Monitoring and Evaluation Plan V1.0 2020 Contents Acknowledgement to Country ................................................................................................ 1 Contributors ........................................................................................................................... 1 Abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 Background and context ........................................................................................................ 3 About the Rivers MEP ............................................................................................................. 7 Part A: PERFORMANCE OBJECTIVES ..................................................................................... 18 Habitat ................................................................................................................................. 24 Vegetation ............................................................................................................................ 29 Engaged communities .......................................................................................................... 45 Community places ................................................................................................................ 54 Water for the environment .................................................................................................. -

Lang Lang Foreshore Reserve Coastal Management Plan Lang Lang Foreshore Reserve Coastal Management Plan

Lang Lang Foreshore Reserve Coastal Management Plan Lang Lang Foreshore Reserve Coastal Management Plan Prepared by Connell Wagner Pty Ltd on behalf of Lang Lang Foreshore Committee of Management Inc. and the Department of Sustainability and Environment Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment Melbourne, January 2005 Also published on www.dse.vic.gov.au © The State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2005 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. Printed by EzyColour Copy Centre, 1/899 Whitehorse Road, Box Hill Victoria 3128 ISBN 1 74152 096 7 For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre 136 186 Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Note: The Hon. John Thwaites MP, Minister for Environment, has approved the Lang Lang Foreshore Reserve Coastal Management Plan, pursuant to Section 32 of the Coastal Management Act 1995. The Coastal Management Plan takes effect on 16 December 2004, the date that Notice of Approval was published in the Victorian Government Gazette (G.51, page 3392). A person using Connell Wagner documents or data accepts the risk of: a) Using the documents or data in electronic form without requesting and checking them for accuracy against the original hard copy version; and b) Using the documents or data for any purpose not agreed to in writing by Connell Wagner. -

DUCK HUNTING in VICTORIA 2020 Background

DUCK HUNTING IN VICTORIA 2020 Background The Wildlife (Game) Regulations 2012 provide for an annual duck season running from 3rd Saturday in March until the 2nd Monday in June in each year (80 days in 2020) and a 10 bird bag limit. Section 86 of the Wildlife Act 1975 enables the responsible Ministers to vary these arrangements. The Game Management Authority (GMA) is an independent statutory authority responsible for the regulation of game hunting in Victoria. Part of their statutory function is to make recommendations to the relevant Ministers (Agriculture and Environment) in relation to open and closed seasons, bag limits and declaring public and private land open or closed for hunting. A number of factors are reviewed each year to ensure duck hunting remains sustainable, including current and predicted environmental conditions such as habitat extent and duck population distribution, abundance and breeding. This review however, overlooks several reports and assessments which are intended for use in managing game and hunting which would offer a more complete picture of habitat, population, abundance and breeding, we will attempt to summarise some of these in this submission, these include: • 2019-20 Annual Waterfowl Quota Report to the Game Licensing Unit, New South Wales Department of Primary Industries • Assessment of Waterfowl Abundance and Wetland Condition in South- Eastern Australia, South Australian Department for Environment and Water • Victorian Summer waterbird Count, 2019, Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research As a key stakeholder representing 17,8011 members, Field & Game Australia Inc. (FGA) has been invited by GMA to participate in the Stakeholder Meeting and provide information to assist GMA brief the relevant Ministers, FGA thanks GMA for this opportunity. -

City of Greater Dandenong Green Wedge Water Issues and Constraints

DRAFT FINAL REPORT ISSUES PAPER: City of Greater Dandenong Green Wedge Water issues and constraints December 2013 Document history Revision: Revision no. 056 Author/s Ross Hardie Clare Ferguson Rob Catchlove Checked Ross Hardie Approved Rob Catchlove Revision no. 05 Author/s Ross Hardie Clare Ferguson Rob Catchlove Checked Ross Hardie Approved Rob Catchlove Revision no. 04 Author/s Ross Hardie Clare Ferguson Rob Catchlove Checked Ross Hardie Approved Rob Catchlove Revision no. 02 Author/s Ross Hardie Clare Ferguson Rob Catchlove Checked Ross Hardie Approved Rob Catchlove Revision no. 01 Author/s Ross Hardie Rob Catchlove Checked Ross Hardie Approved Rob Catchlove Distribution: Revision no. 06 Issue date 19 December 2013 Issued to Ceinwen Gould (City of Greater Dandenong) and Chantal Lenthall (Planisphere) Description: Draft Final Report. Water issues and constraints paper Citation: Alluvium, 2013. City of Greater Dandenong Green Wedge: Water issues and constraints. Report for City of Greater Dandenong. Ref: R:\Projects\2013\074_Green_Wedge_Master_Plan\1_Deliverables\ Draft Final\P113074_R01_V06b_Green_Wedge_issues and constraints.docx Executive Summary This paper provides a discussion on water related issues associated with the City of Greater Dandenong Green Wedge. The paper is first in a series of water related papers developed to assist in the development of a Management Plan for the City of Greater Dandenong Green Wedge Land uses in the City of Greater Dandenong Green Wedge There are many land uses associated with the City of Greater -

The Gippsland Lakes Fishery

The Gippsland Lakes fishery An overview The Gippsland Lakes are a network of lakes, marshes and lagoons in east Gippsland, covering an area of about 354 square kilometres. The waterway is collectively fed by the Avon-Perry, Latrobe, Mitchell, Nicholson and Tambo rivers and a number of smaller creeks and comprises several large lakes including Lake Wellington, Lake King and Lake Victoria. The region supports a range of natural values important to fisheries resources and is home to several commercial and recreational fisheries. Fishing in the Lakes provides significant value to recreational and commercial fishers, consumers of commercially caught fish and the broader local community. Both sectors are economically important to the region. Commercial fishing in Gippsland Lakes Commercial fishing in Gippsland Lakes is authorised under a number of commercial fishing licences. Those that use nets to harvest fish include Gippsland Lakes Fishery Access Licences, Gippsland Lakes (Bait) Fishery Access Licences and Eel Fishery Access Licences. There are currently ten Gippsland Lakes Fishery Access Licence holders who use a range of methods (mostly mesh and haul seine nets) to harvest a range of species, ten Gippsland Lakes (Bait) Fishery Access Licence holders who use dip and seine nets (and other equipment) to harvest species such as anchovies, spider crabs, bass yabby and marine worms and two Eel Fishery Access Licence holders who use fyke nets to catch long and short finned eels. Commercial catch and value The annual catch of all species by commercial fishers in the Gippsland Lakes since the 1978/79 fishing season can be seen in Figure 1. -

Victorian Coastal Awards for Excellence 2008

1 coastlineEdition 43. ISSN 1329-0835 autumn update 2008 State Coordinator’s Message In this issue Matthew Fox Statewide Program Coordinator State Coordinator’s Message 1 I’d like to welcome you to Coastline Autumn Update; the first for me in the role of State Coordinator, Approach to diversity and the first in this new newsletter format. The new-look newsletter has been developed to better rewarded 1 inform those with an interest in Victoria’s coast. There will be an issue in autumn, winter and spring Keeping up with change 2 Victorian Coastal Awards and in summer, the usual Coastline magazine will be printed and distributed. In the interests of for Excellence 2008 2 reducing our environmental footprint, we have decided to distribute this newsletter electronically. Twitchers wanted 3 By doing so, we have already saved more than half a tonne of paper, as well as avoiding the few Coastal heroes 3 hundred kilograms of carbon emissions involved in the statewide transport process. We hope that you Rangers vegetation management workshop 3 find theCoastline Update both informative and useful, and we welcome your contributions. If you Coastal Fun 4 Kids 4 would like to contribute to the Update, please drop us a line or contact your local facilitator. Apollo Bay Music Festival cooler than ever 4 Evolution of estuary monitoring 4 Approach to diversity rewarded Venus Bay fox control project 5 The efforts of the Coast Action/Coastcare Easter by the Estuary 5 (CA/CC) team to build inclusiveness into its Grants available for volunteers 6 programs and projects, has been recognised Reporting on catchment health 6 with a DisAbility award from the Department of Coming Events 6 Coast Action/ Sustainability and Environment. -

Technical Note 007 Response to RFI

GAS IMPORT JETTY AND PIPELINE PROJECT ENVIRONMENT EFFECTS STATEMENT INQUIRY AND ADVISORY COMMITTEE TECHNICAL NOTE TECHNICAL NOTE NUMBER: TN 007 DATE: 2 October 2020 LOCATION: Crib Point Jetty Works EES/MAP BOOK REFERENCE: Technical Report A Response to RFI 021 – Section 2.5: Chlorine and temperature SUBJECT: discharge conditions The documents attached to this technical note are those SUMMARY completed by CEE between 2014 and 2018 and referred to in the "Reference List" of Technical Report A. Provide links to the reports referenced in EES Technical Report REQUEST: A completed by CEE between 2014 to 2018 Annexure A-A. NOTE: 1. We understand this request to be referring to the CEE reports listed in the reference list to Technical Report A. Documents 2. The following documents are provided as attachments to this technical note: (a) CEE (2014a). North Arm Subtidal Seagrass and Water Quality Monitoring. Spatial variation in subtidal seagrass depth limits in Western Port, February 2014. Report to Port of Hastings Development Authority. (b) Appendix of CEE (2014a). North Arm Subtidal Seagrass and Water Quality Monitoring. Spatial variation in subtidal seagrass depth limits in Western Port, February 2014. Report to Port of Hastings Development Authority. (c) CEE (2014b). Port of Hastings Seagrass Monitoring Pilot Study. Report to Port of Hastings Development Authority. CEE Melbourne June 2014. (d) CEE (2017). Long Island point: Wastewater Discharge - AGL Gas Import Jetty and Pipeline Project. Report for AGL. (e) CEE (2018a). Plume Modelling of Discharge from LNG Facility at Crib Point, Western Port – AGL Gas Import Jetty and Pipeline Project. Report for AGL. -

Download Full Article 2.9MB .Pdf File

June 1946 MEM. NAT. Mus. V1cT., 14, PT. 2, 1946. https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1946.14.06 THE SUNKLANDS OF PORT PHILLIP BAY AND BASS STRAIT By R. A. Keble, F.G.S., Palaeontologist, National Jiiiseurn of Victoria. Figs. 1-16. (Received for publication 18th l\fay, 1945) The floors of Port Phillip Bay and Bass Strait were formerly portions of a continuous land surface joining Victoria with Tasmania. This land surface was drained by a river system of which the Riv-er Y arra was part, and was intersected by two orogenic ridges, the Bassian and King Island ridges, near its eastern and western margins respectively. \Vith progressive subsidence and eustatic adjustment, these ridges became land bridges and the main route for the migration of the flora and fauna. At present, their former trend is indicated by the chains of islands in Bass Strait and the shallower portions of the Strait. The history of the development of the River Yarra is largely that of the former land surface and the King Island land bridge, and is the main theme for this discussion. The Yarra River was developed, for the most part, during the Pleistocene or Ice Age. In Tasmania, there is direct evidence of the Ice Age in the form of U-shaped valleys, raised beaches, strandlines, and river terraces, but in Victoria the effects of glaciation are less apparent. A correlation of the Victorian with the Tasmanian deposits and land forms, and, incidentally, with the European and American, can only be obtained by ascertaining the conditions of sedimentation and accumulation of such deposits in Victoria, as can be seen at the surface1 or as have been revealed by bores, particularly those on the N epean Peninsula; by observing the succession of river terraces along the Maribyrnong River; and by reconstructing the floor of Port Phillip Bay, King Bay, and Bass Strait, and interpreting the submerged land forms revealed by the bathymetrical contours. -

5. South East Coast (Victoria)

5. South East Coast (Victoria) 5.1 Introduction ................................................... 2 5.5 Rivers, wetlands and groundwater ............... 19 5.2 Key data and information ............................... 3 5.6 Water for cities and towns............................ 28 5.3 Description of region ...................................... 5 5.7 Water for agriculture .................................... 37 5.4 Recent patterns in landscape water flows ...... 9 5. South East Coast (Vic) 5.1 Introduction This chapter examines water resources in the Surface water quality, which is important in any water South East Coast (Victoria) region in 2009–10 and resources assessment, is not addressed. At the time over recent decades. Seasonal variability and trends in of writing, suitable quality controlled and assured modelled water flows, stores and levels are considered surface water quality data from the Australian Water at the regional level and also in more detail at sites for Resources Information System (Bureau of Meteorology selected rivers, wetlands and aquifers. Information on 2011a) were not available. Groundwater and water water use is also provided for selected urban centres use are only partially addressed for the same reason. and irrigation areas. The chapter begins with an In future reports, these aspects will be dealt with overview of key data and information on water flows, more thoroughly as suitable data become stores and use in the region in recent times followed operationally available. by a brief description of the region. -

Port Information Handbook Gippsland Lakes

Gippsland Ports Port Information Handbook Part 2 Port of Gippsland Lakes Effective 27th July 2017 The Narrows at Lakes Entrance CONTENTS SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 PREAMBLE .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Purpose ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Disclaimer ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.4 Datum ..................................................................................................................................... 2 1.5 Definitions .............................................................................................................................. 2 1.5.1 Agent ............................................................................................................................... 2 1.5.2 Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) ................................................................ 2 1.5.3 Berthed Vessel ................................................................................................................. 2 1.5.4 Bunkering Operations ...................................................................................................... 2 1.5.5 Cargo............................................................................................................................... -

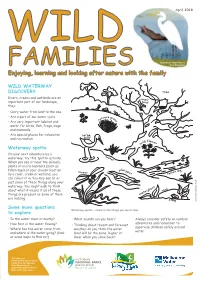

Enjoying, Learning and Looking After Nature with the Family

April 2018 Illustration: Rhyll Plant & Jess McGeachin Enjoying, learning and looking after nature with the family WILD WATERWAY DISCOVERY tree Rivers, creeks and wetlands are an small important part of our landscape, bird they: • Carry water from land to the sea. • Are a part of our water cycle. sock gr us as • Are very important habitat and t s water for birds, fish, frogs, bugs and mammals. • Are special places for relaxation large and recreation. bird ild flowe w r Waterway spotto On your next adventure by a wat waterway, try this ‘spotto’ activity. er When you see or hear the animals, plants or micro-habitats (such as fallen logs) at your chosen location platy g insec pu en lo by a river, creek or wetland, you t s fall can colour it in. You may see all or just some of these things along your waterway. You might wish to think nt about what it means if all of these pla ck ter ro things are present or some of them wa are missing. frog Renee Treml Artwork by Some more questions Waterway spotto – colour in the things you see or hear. to explore • Is the water clear or murky? • What sounds can you hear? Always consider safety on outdoor adventures and remember to • How fast is the water flowing? • Thinking about recent and forecast supervise children safely around • Where has the water come from weather do you think the water water. and where is the water going? (look level will be the same, higher or at some maps to find out) lower when you come back? This edition of Wild Families was produced by the Victorian National Parks Association in partnership with Melbourne Water and Living Links WILD PLACE Winton Wetlands on the Dandenong Creek are a wonderful place to spot wildlife. -

'The Councils'

IN THE MATTER OF THE CRIB POINT GAS IMPORT JETTY & PIPELINE PROJECT OPENING 1. This Opening is made on behalf of Mornington Peninsula and Bass Coast Shire Councils (‘the Councils’). 2. As councils under the Local Government Act 2020, the Councils are required to give effect to the ‘overarching governance principles’ set out in s9 of that Act. Relevantly, these principles include: (b) priority is to be given to achieving the best outcomes for the municipal community, including future generations; (c) the economic, social and environmental sustainability of the municipal district, including mitigation and planning for climate change risks, is to be promoted; (d) the municipal community is to be engaged in strategic planning and strategic decision making; 3. The Councils submit that the ‘best outcome for the municipal community’, including in particular future generations, is for the IAC to recommend that the Project not proceed. THE CONTEXT 4. Context is always critical in planning decision-making. What may be perfectly acceptable in one context may be entirely unacceptable in another. The most critical part of the context for the IAC’s decision is that the Project is situated in Western Port. 5. Western Port is one of the jewel in Victoria’s crown. GHD’s Ecology Description, prepared in 2014 as part of a proposal to expand the Port of Hastings, provides a convenient overview: Western Port is a coastal embayment in central Victoria, east of Port Phillip Bay and approximately 70 kilometres southeast of Melbourne. It is bounded by the Mornington Peninsula to the west, Koo Wee Rup to the north, Phillip Island to the south and features French Island at its centre.