Lesotho Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 21: the State of Poverty and Food Insecurity in Maseru, Lesotho

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier African Food Security Urban Network Reports and Papers 2015 No. 21: The State of Poverty and Food Insecurity in Maseru, Lesotho Resetselemang Leduka Jonathan Crush Balsillie School of International Affairs/WLU, [email protected] Bruce Frayne Southern African Migration Programme Cameron McCordic Balsillie School of International Affairs/WLU Thope Matobo See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/afsun Part of the Food Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Leduka, R., Crush, J., Frayne, B., McCordic, C., Matobo, T., Makoa, T., Mphale, M., Phaila, M., Letsie, M. (2015). The State of Poverty and Food Insecurity in Maseru, Lesotho (rep., pp. i-80). Kingston, ON and Cape Town: African Food Security Urban Network. Urban Food Security Series No. 21. This AFSUN Urban Food Security Series is brought to you for free and open access by the Reports and Papers at Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in African Food Security Urban Network by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Resetselemang Leduka, Jonathan Crush, Bruce Frayne, Cameron McCordic, Thope Matobo, Ts’episo Makoa, Matseliso Mphale, Mmantai Phaila, and Moipone Letsie This afsun urban food security series is available at Scholars Commons @ Laurier: https://scholars.wlu.ca/afsun/11 AFRICAN FOOD SECURITY URBAN NETWORK (AFSUN) THE STATE OF POVERTY AND FOOD INSECURITY IN MASERU, LESOTHO URBAN FOOD SECURITY SERIES NO. 21 AFRICAN FOOD SECURITY URBAN NETWORK (AFSUN) THE STATE OF POVERTY AND FOOD INSECURITY IN MASERU, LESOTHO RESETSELEMANG LEDUKA, JONATHAN CRUSH, BRUCE FRAYNE, CAMERON MCCORDIC, THOPE MATOBO, TS’EPISO E. -

American Embassy Kinshasa – GSO Shipping & Customs Office

Kinshasa American Embassy GSO Shipping & Customs Office American Embassy Kinshasa – GSO Shipping & Customs Office 498 Av. Colonel Lukusa Kinshasa, D.R. Congo REQUEST FOR SEA FREIGHT SERVICES Tender # S/2021/1 July 29, 2021 1. American Embassy Kinshasa Tender requirements a) Please provide American Embassy Kinshasa with your most favorable sea freight rates, up to free arrival destination, valid from September 13, 2021 through September 12, 2022. The destinations on the attached spreadsheet are split into two lists. One list contains the normal authorized destinations (Tab – Regular Destinations) as usual, and the second list (Tab – Worldwide Destinations) shows a set of other destinations. Forwarders/Maritime lines can quote on both lists, but only the first list (Tab – Regular Destinations) is obligatory to make your quote valid. b) Rates provided are for sea freight from Matadi Port to final destination Port and must cover sea carriage all the way. For the fuel and security surcharge, see “Special Provision” section “g” below. c) Rates are to be quoted in U.S. Dollars only and only to two numbers behind the decimal point (no other currency). d) Routings: You are required to show indirect routings (in case voyages are not non-stop). Please indicate those destinations on a separate sheet that require such indirect routings. e) Please advise Hazardous Material fee per shipment. f) U.S. Ocean carriers must be used if available. g) Special Provision – FUEL and SECURITY surcharge ADJUSTMENT Based on the fluctuating prices of fuel, forwarders/maritime lines must quote separately for the fuel and security surcharge. Backup documents must be provided for any change. -

Oral Poetry As Channel for Communication

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 8, No. 4, 2012, pp. 20-23 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020120804.365 www.cscanada.org Oral Poetry as Channel for Communication A. Anthony Obaje[a],*; Bola Olajide Yakubu[b] [a] Department of English and Literary Studies, Faculty of Arts and from one generation to another. It is also called African Humanities, Kogi State University, Anyigba, Nigeria. traditional poetry whose modus operandi is collective [b] Department of Theatre Arts, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Kogi State University, Anyigba, Nigeria. participation. It can be described as a collective experience *Corresponding author. that is initiated by an individual in a group and shared by the rest of the group; it is a common heritage shared by all Received 1 June 2012; accepted 5 August 2012 and handed over from one generation to another. African oral poetry was not meant traditionally for a few or a Abstract particular group, but for the entirety of the community. It African village traditionally was a small unit where is the culture, heritage and pride of a particular African every inhabitant knew and was interested in the affair society where such oral poetry is created and performed. of his neighbor. This common heritage produces poems In other words it is not the property of a few bards, but passed on by words of mouth from one generation to the entire society. This is because, oral poetry is created another. This paper discusses the transmission of African and effectively used to create the desired atmosphere and socio-cultural values from one generation to another evoke the appropriate emotion as conditioned by occasion through oral poetry. -

The State of Food Insecurity in Windhoek, Namibia

THE STATE OF FOOD INSECURITY IN WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA Wade Pendleton, Ndeyapo Nickanor and Akiser Pomuti Pendleton, W., Nickanor, N., & Pomuti, A. (2012). The State of Food Insecurity in Windhoek, Namibia. AFSUN Food Security Series, (14). AFRICAN FOOD SECURITY URBAN NETWORK (AFSUN) AFRICAN FOOD SECURITY URBAN NETWORK (AFSUN) THE STATE OF FOOD INSECURITY IN WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA URBAN FOOD SECURITY SERIES NO. 14 AFRICAN FOOD SECURITY URBAN NETWORK (AFSUN) THE STATE OF FOOD INSECURITY IN WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA WADE PENDLETON, NDEYAPO NICKANOR AND AKISER POMUTI SERIES EDITOR: PROF. JONATHAN CRUSH URBAN FOOD SECURITY SERIES NO. 14 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The financial support of the Canadian International Development Agency for AFSUN and this publication is acknowledged. Cover Photograph: Aaron Price, http://namibiaafricawwf.blogspot.com Published by African Food Security Urban Network (AFSUN) © AFSUN 2012 ISBN 978-1-920597-01-6 First published 2012 Production by Bronwen Müller, Cape Town All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans- mitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the publisher. Authors Wade Pendleton is a Research Associate of the African Food Security Urban Network. Ndeyapo Nickanor is a Lecturer at the University of Namibia. Akiser Pomuti is Director of the University Central Consultancy Bureau at the University of Namibia. Previous Publications in the AFSUN Series No 1 The Invisible Crisis: Urban Food Security in Southern Africa No 2 The State of Urban Food Insecurity in Southern Africa No -

The Case of African Cities

Towards Urban Resource Flow Estimates in Data Scarce Environments: The Case of African Cities The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Currie, Paul, et al. "Towards Urban Resource Flow Estimates in Data Scarce Environments: The Case of African Cities." Journal of Environmental Protection 6, 9 (September 2015): 1066-1083 © 2015 Author(s) As Published 10.4236/JEP.2015.69094 Publisher Scientific Research Publishing, Inc, Version Final published version Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/124946 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license Detailed Terms https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Journal of Environmental Protection, 2015, 6, 1066-1083 Published Online September 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jep http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jep.2015.69094 Towards Urban Resource Flow Estimates in Data Scarce Environments: The Case of African Cities Paul Currie1*, Ethan Lay-Sleeper2, John E. Fernández2, Jenny Kim2, Josephine Kaviti Musango3 1School of Public Leadership, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa 2Department of Architecture, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA 3School of Public Leadership, and the Centre for Renewable and Sustainable Energy Studies (CRSES), Stellenbosch, South Africa Email: *[email protected] Received 29 July 2015; accepted 20 September 2015; published 23 September 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Data sourcing challenges in African nations have led many African urban infrastructure develop- ments to be implemented with minimal scientific backing to support their success. -

African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries Compiled by Mette Shayne Revised Summer 1999

African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries Compiled by Mette Shayne Revised Summer 1999 INTRODUCTION This union list updates African Newspapers Currently Received by American Libraries compiled by Daniel A. Britz, Working Paper no. 8 African Studies Center, Boston, 1979. The holdings of 19 collections and the Foreign Newspapers Microfilm Project were surveyed during the summer of 1999. Material collected currently by Library of Congress, Nairobi (marked DLC#) is separated from the material which Nairobi sends to Library of Congress in Washington. The decision was made to exclude North African papers. These are included in Middle Eastern lists and in many of the reporting libraries entirely separate division handles them. Criteria for inclusion of titles on this list were basically in accord with the UNESCO definition of general interest newspapers. However, a number of titles were included that do not clearly fit into this definition such as religious newspapers from Southern Africa, and labor union and political party papers. Daily and less frequently published newspapers have been included. Frequency is noted when known. Sunday editions are listed separately only if the name of the Sunday edition is completely different from the weekday edition or if libraries take only the Sunday or only the weekday edition. Microfilm titles are included when known. Some titles may be included by one library, which in other libraries are listed as serials and, therefore, not recorded. In addition to enabling researchers to locate African newspapers, this list can be used to rationalize African newspaper subscriptions of American libraries. It is hoped that this list will both help in the identification of gaps and allow for some economy where there is substantial duplication. -

AFRICAN CENTRE for LEGAL EXCELLENCE 2017 Application Form

AFRICAN CENTRE FOR LEGAL EXCELLENCE Building Africa’s Legal Infrastructure to Enhance Economic Development 2017 Application Form Complete this application form in typed or legibly written English and submit to ILI–ACLE via e-mail. PERSONAL INFORMATION Surname First name Other name(s) Gender Male Female Home Address Mobile Telephone E-mail Address Office Telephone Name of Organisation/Company Position/Title Business Physical Address Organization’s E-mail Address Please explain your reason for applying for this programme, how it relates to your work and what you anticipate to derive from it in furthering your current responsibilities. Kampala Office: East African Development Bank Building-4th Floor, 4 Nile Avenue, P. O. Box 23933 Kampala, Uganda • Tel: (+256) 414.347.523 Maseru Office: Lancer’s Inn, Kingsway, Private Bag A469, Maseru, Lesotho • Email: [email protected] Nairobi Office: Lavington Green, Nairobi, Kenya • Tel: (+254) 735.083.634 Email: [email protected]• Web: www.iliacle.org AFRICAN CENTRE FOR LEGAL EXCELLENCE Building Africa’s Legal Infrastructure to Enhance Economic Development Describe your current job responsibilities and professional experience relating to the training programme. (Please attach a copy of your curriculum vitae.) How did you learn about ILI-ACLE? (Check the best alternative(s) and specify your resource as appropriate.) I am an ILI-ACLE Alumnus/Alumna ……………………………………………………………… Recommendation from ILI-ACLE Alumnus/Alumna …………………………………………......... ILI-ACLE Website……………………………………………………………………………………. Target Email…………………………………………………………………………………………… ILI-ACLE Brochure……………………………………………………………………………………. Newspaper……………………………………………………………………………………………… Radio…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Billboard (indicate country)….………………………………………………………………………….. Other……………………………………………………………………………………………………. Payment Information Course Fees: Course fees for all locations include the cost of programme facilitation and administration, ILI- ACLE certification, tea/coffee on seminar days, seminar materials and stationery. -

Supplemental Infomation Supplemental Information 119 U.S

118 Supplemental Infomation Supplemental Information 119 U.S. Department of State Locations Embassy Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire Dushanbe, Tajikistan Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Freetown, Sierra Leone Accra, Ghana Gaborone, Botswana Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Georgetown, Guyana Algiers, Algeria Guatemala City, Guatemala Almaty, Kazakhstan Hanoi, Vietnam Amman, Jordan Harare, Zimbabwe Ankara, Turkey Helsinki, Finland Antananarivo, Madagascar Islamabad, Pakistan Apia, Samoa Jakarta, Indonesia Ashgabat, Turkmenistan Kampala, Uganda Asmara, Eritrea Kathmandu, Nepal Asuncion, Paraguay Khartoum, Sudan Athens, Greece Kiev, Ukraine Baku, Azerbaijan Kigali, Rwanda Bamako, Mali Kingston, Jamaica Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Kinshasa, Democratic Republic Bangkok, Thailand of the Congo (formerly Zaire) Bangui, Central African Republic Kolonia, Micronesia Banjul, The Gambia Koror, Palau Beijing, China Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Beirut, Lebanon Kuwait, Kuwait Belgrade, Serbia-Montenegro La Paz, Bolivia Belize City, Belize Lagos, Nigeria Berlin, Germany Libreville, Gabon Bern, Switzerland Lilongwe, Malawi Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan Lima, Peru Bissau, Guinea-Bissau Lisbon, Portugal Bogota, Colombia Ljubljana, Slovenia Brasilia, Brazil Lomé, Togo Bratislava, Slovak Republic London, England, U.K. Brazzaville, Congo Luanda, Angola Bridgetown, Barbados Lusaka, Zambia Brussels, Belgium Luxembourg, Luxembourg Bucharest, Romania Madrid, Spain Budapest, Hungary Majuro, Marshall Islands Buenos Aires, Argentina Managua, Nicaragua Bujumbura, Burundi Manama, Bahrain Cairo, Egypt Manila, -

An Analysis of Alcohol and Cigarette Prices in Maseru, Gaborone, and Neighboring South African Towns

: TRADE A GLOBAL REVIEW OF COUNTRY EXPERIENCES BOTSWANA, LESOTHO, AND SOUTH AFRICA: AN ANALYSIS OF ALCOHOL AND CIGARETTE PRICES IN MASERU, GABORONE, AND NEIGHBORING SOUTH AFRICAN TOWNS TECHNICAL REPORT OF THE WORLD BANK GROUP GLOBAL TOBACCO CONTROL PROGRAM. CONFRONTING EDITOR: SHEILA DUTTA ILLICIT TOBACCO BOTSWANA, LESOTHO, AND SOUTH AFRICA 19 BOTSWANA, LESOTHO, AND SOUTH AFRICA An Analysis of Alcohol and Cigarette Prices in Maseru, Gaborone, and Neighboring South African Towns Kirsten van der Zee and Corné van Walbeek1 Chapter Summary The government of Lesotho plans to implement a levy on tobacco and alcohol products. The proposed measure is similar to levies that have been implemented in Botswana in recent years. A concern is the possibility that Lesotho’s new levy may stimulate a significant increase in bootlegging between Lesotho and South Africa. This chapter investigates the presence and possibility of bootlegging between South Africa and Botswana, and South Africa and Lesotho, by describing the differences in cigarette and alcohol prices between Gaborone, Botswana, and the nearby South African towns of Mafikeng and Zeerust, as well as between Maseru, Lesotho, and nearby Ladybrand, South Africa. 1 Economics of Tobacco Control Project, University of Cape Town, South Africa. 551 551 Confronting Illicit Tobacco Trade: A Global Review of Country Experiences An analysis of comparative cigarette price data indicated the following: Gaborone and Mafikeng/Zeerust. Overall, average cigarette prices are significantly higher in Gaborone than in nearby South African towns. The cheapest pack price found in Gaborone was nearly five times the cheapest price identified in South Africa. Maseru and Ladybrand. Cigarette prices differ between Maseru and Ladybrand, but much less than between Gaborone and Mafikeng/Zeerust. -

Urban Development Project for Lesotho

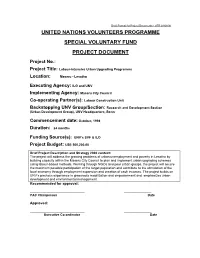

Draft Format for Project Documents - GTR 07/08/97 UNITED NATIONS VOLUNTEERS PROGRAMME SPECIAL VOLUNTARY FUND PROJECT DOCUMENT Project No.: Project Title: Labour-intensive Urban Upgrading Programme Location: Maseru - Lesotho Executing Agency: ILO and UNV Implementing Agency: Maseru City Council Co-operating Partner(s): Labour Construction Unit Backstopping UNV Group/Section: Research and Development Section (Urban Development Group), UNV Headquarters, Bonn Commencement date: October, 1998 Duration: 24 months Funding Source(s): UNV’s SVF & ILO Project Budget: US$ 500,200.00 Brief Project Description and Strategy 2000 context: The project will address the growing problems of urban unemployment and poverty in Lesotho by building capacity within the Maseru City Council to plan and implement urban upgrading schemes using labour-based methods. Working through NGOs and poor urban groups, the project will secure the maximum possible participation of the target population and contribute to the stimulation of the local economy through employment expansion and creation of cash incomes. The project builds on UNV’s previous experience in grassroots mobilization and empowerment and emphasizes urban development and environmental management. Recommended for approval: ______________________________ _______________ PAC Chairperson Date Approved: ______________________________ _______________ Executive Co-ordinator Date 1. BACKGROUND & JUSTIFICATION 1.1 Country Context Lesotho ranks among the world’s poorest countries and falls in the category of least developed countries (LDCs). Within the 12-member Southern African Development Community (SADC), it has the 6th lowest per capita GDP and the 11th lowest export receipts. Unemployment rate in the country is equally one of the highest in the region and has been growing in recent years, even among University graduates. -

January 2020

Nonimmigrant Visa Issuances by Post January 2020 (FY 2020) Post Visa Class Issuances Abidjan A1 8 Abidjan A2 8 Abidjan B1/B2 443 Abidjan C1 1 Abidjan C1/D 5 Abidjan F1 68 Abidjan F2 1 Abidjan G1 1 Abidjan G2 1 Abidjan G4 10 Abidjan G5 1 Abidjan H1B 4 Abidjan I 0 Abidjan J1 5 Abidjan K1 7 Abidjan L1 1 Abidjan O2 1 Abidjan R1 1 Abidjan R2 2 Abu Dhabi A1 4 Abu Dhabi A2 66 Abu Dhabi A3 9 Abu Dhabi B1 17 Abu Dhabi B1/B2 1,095 Abu Dhabi B2 1 Abu Dhabi C1/D 12 Abu Dhabi D 3 Abu Dhabi E3 1 Abu Dhabi F1 72 Abu Dhabi F2 4 Abu Dhabi G2 1 Abu Dhabi H1B 6 Abu Dhabi H4 7 Abu Dhabi J1 9 Abu Dhabi J2 3 Abu Dhabi K1 41 Abu Dhabi K2 2 Abu Dhabi L1 3 Abu Dhabi L2 6 Abu Dhabi M1 0 Abu Dhabi R1 1 Abuja A2 159 Page 1 of 109 Nonimmigrant Visa Issuances by Post January 2020 (FY 2020) Post Visa Class Issuances Abuja B1/B2 2,148 Abuja C1 3 Abuja C1/D 4 Abuja D 0 Abuja E2 2 Abuja F1 99 Abuja F2 19 Abuja G1 4 Abuja G2 6 Abuja G4 28 Abuja G5 1 Abuja H1B 22 Abuja H4 4 Abuja I 3 Abuja J1 13 Abuja J2 8 Abuja L1 8 Abuja L2 11 Abuja M1 7 Abuja O1 4 Abuja O2 1 Abuja O3 1 Abuja P1 2 Abuja P3 2 Abuja R1 10 Abuja R2 1 Accra A1 1 Accra A2 29 Accra B1 1 Accra B1/B2 1,036 Accra B2 1 Accra C1 0 Accra C1/D 13 Accra F1 68 Accra F2 8 Accra G1 2 Accra G2 12 Accra G4 6 Accra H1B 16 Accra H4 13 Accra I 2 Accra J1 24 Page 2 of 109 Nonimmigrant Visa Issuances by Post January 2020 (FY 2020) Post Visa Class Issuances Accra J2 8 Accra K1 18 Accra L1 2 Accra L2 2 Accra M1 1 Accra O1 2 Accra P1 3 Accra P3 0 Accra R1 10 Addis Ababa A2 8 Addis Ababa B1 1 Addis Ababa B1/B2 1,125 Addis Ababa C1/D -

World in One Country

World in One Country World in One Country 20 days | Johannesburg to Cape Town SMALL GROUP ACCOMMODATED • Kingdom of Eswatini - explore the • Transportation in a suitable touring SAFARI :The South African safari Mlilwane Wildlife Sanctuary and visit the vehicle according to group size (Toyota that has it all! Wonderful wildlife, Umphakatsi Chief's homestead Quantum, Mercedes Benz Sprinter, Vito • Cape Town - see the highlights of the or other appropriate vehicle) breathtaking scenery and insights southern tip of Africa on a Cape Peninsula • Services of an experienced local guide/ into culture and history. Travel from tour, including Hout Bay and the penguins driver Jo'burg to Kruger National Park, at Boulder's Beach • Games drives - Kruger National Park, through the Kingdom of Eswatini • iSimangaliso Wetland Park - take to the Hluhluwe and onto Zululand. Hike in the water of the St Lucia estuary on a boat Umfolozi Game Reserve, Addo Elephant Drakensberg Mountains and go cruise in search of hippos and crocodiles National Park • Drakensberg Mountains - hike in the • Lesotho - pony trekking and St Lucia pony trekking in Lesotho. Journey incredible scenery of rugged mountains, Estuary boat cruise south through Addo Elephant indigenous forests and rushing streams • Oudtshoorn - Cango Caves excursion Park with wonderful game viewing • Lesotho - enjoy a pony trek and learn • Robertson - Wine blending experience and the lush Tsitsikamma Forest. about the distinct culture of the Basotho • Cape Peninsula tour Before reaching Cape Town, visit people • What's Not Included Oudtshoorn's Cango Caves and the Addo Elephant National Park - spot elephants, rhinos, lions and more on an • Tipping - an entirely personal gesture Wine Route.