More Than Just a Game: the Impact of Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Fall Commencement

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Commencement Programs Office of Student Affairs Fall 2020 2020 Fall Commencement Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/commencement- programs Part of the Higher Education Commons This brochure is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of Student Affairs at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commencement Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Twenty-Ninth Annual Fall Commencement 2020 Georgia Southern University SCHEDULE OF CEREMONIES UNDERGRADUATE Sunday, Dec. 13 • 2 p.m. • Savannah Convention Center Wednesday, Dec. 16 • 10 a.m. • Paulson Stadium in Statesboro Wednesday, Dec. 16 • 3 p.m. • Paulson Stadium in Statesboro Thursday, Dec. 17 • 10 a.m. • Paulson Stadium in Statesboro GRADUATE Thursday, Dec. 17 • 3 p.m. • Paulson Stadium in Statesboro COMMENCEMENT NOTES Photography: A professional photographer will take Accessibility Access: If your guest requires a picture of you as you cross the stage. A proof of accommodations for a disability, accessible seating this picture will be emailed to you at your Georgia is available. Guests entering the stadium from the Southern email address and mailed to your home designated handicap parking area should enter address so that you may decide if you wish to through the Media Gate or Gate 13 (Statesboro purchase these photos. Find out more about this Ceremony). Accessible seating for the Savannah service at GradImages.com. ceremonies are available on the right hand side near the back of the Exhibit Hall. -

The Following Players Comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set

COLLEGE FOOTBALL GREAT TEAMS OF THE PAST 2 SET ROSTER The following players comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. 1971 NEBRASKA 1971 NEBRASKA 1972 USC 1972 USC OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Woody Cox End: John Adkins EB: Lynn Swann TA End: James Sims Johnny Rodgers (2) TA TB, OA Willie Harper Edesel Garrison Dale Mitchell Frosty Anderson Steve Manstedt John McKay Ed Powell Glen Garson TC John Hyland Dave Boulware (2) PA, KB, KOB Tackle: John Grant Tackle: Carl Johnson Tackle: Bill Janssen Chris Chaney Jeff Winans Daryl White Larry Jacobson Tackle: Steve Riley John Skiles Marvin Crenshaw John Dutton Pete Adams Glenn Byrd Al Austin LB: Jim Branch Cliff Culbreath LB: Richard Wood Guard: Keith Wortman Rich Glover Guard: Mike Ryan Monte Doris Dick Rupert Bob Terrio Allan Graf Charles Anthony Mike Beran Bruce Hauge Allan Gallaher Glen Henderson Bruce Weber Monte Johnson Booker Brown George Follett Center: Doug Dumler Pat Morell Don Morrison Ray Rodriguez John Kinsel John Peterson Mike McGirr Jim Stone ET: Jerry List CB: Jim Anderson TC Center: Dave Brown Tom Bohlinger Brent Longwell PC Joe Blahak Marty Patton CB: Charles Hinton TB. -

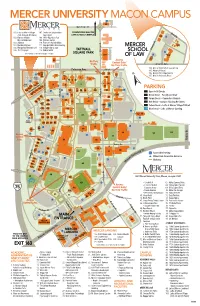

CAMPUS 16 Oglethorpe St

MERCER UNIVERSITY MACON CAMPUS 16 Oglethorpe St. 101. Lofts at Mercer Village 107. Center for Collaborative DOWNTOWN MACON Bond St (2nd, 3rd and 4th floors) Journalism LAW SCHOOL CAMPUS 116 102. Barnes & Noble 108. JAG’s Pizzeria & Pub . Mercer Bookstore 109. Z Beans Coffee . 103. Subway 110. Francar’s Buffalo Wings St 104. Nu-Way Weiners 111. Georgia Public Broadcasting ge 115 105. Margaritas Mexican Grill 112. Indigo Salon & Spa MERCER an 106. The Telegraph 113. WMUB/ESPN TATTNALL Or College St. College SCHOOL Front entrances are wheelchair accessible. SQUARE PARK 100 OF LAW 114 117 42 Access No Thru Control Gate/ Traffic No Thru Traffic Georgia Ave. 114. Mercer University School of Law Coleman Ave. Ash St. 115. Woodruff House 112 116. Orange Street Apartments 113 111 17 18 19 7 6a 117. Mercer University Press Retail 110 1 55 Parking 6 2 6b 5 4 Retail 109 3 20 108 8 9 Parking 101 102 56 107 103 PARKING 106 101 10 12 13 14 15 57 Montpelier104 Ave. Linden Ave. Open to All Decals 105 11 58 Green Decal – Faculty and Staff Adams St. 66 St. College 22 65 Purple Decal – Commuter Students 68 60 64 61 21 Red Decal – Campus Housing Residents 67 69 59 43 Yellow Decal – Lofts at Mercer Village/Tattnall 70 71 62 Blue Decal – Lofts at Mercer Landing 73 25 27 28 23 72 24 26 74 75 76 77 63 Visitor Parking 78 79 80 81 31 32 82 29 30 83 34 54 Access 53 Control 33 Gate 84 44 35 St. -

Valdosta State University Fact Book 2015-2016

Valdosta State University Fact Book 2015-2016 Office of Institutional Research VSU Fact Book 2015-2016 Table of Contents Cover Page.............................................................................................................. Foreword.................................................................................................................. 1 General Information................................................................................................ 2 Brief Chronology of VSU............................................................................................ 3 Concise Mission Statement....................................................................................... 4 Strategic Goals 2013-2019......................................................................................... 5 Board of Regents Membership.................................................................................... 6 Board of Regents Organizational Chart........................................................................ 7 VSU Organizational Chart.......................................................................................... 8 Biography of President............................................................................................... 9 Accreditation............................................................................................................ 10 Degrees Offered........................................................................................................ 11 Undergraduate...................................................................................................... -

All-Time All-America Teams

1944 2020 Special thanks to the nation’s Sports Information Directors and the College Football Hall of Fame The All-Time Team • Compiled by Ted Gangi and Josh Yonis FIRST TEAM (11) E 55 Jack Dugger Ohio State 6-3 210 Sr. Canton, Ohio 1944 E 86 Paul Walker Yale 6-3 208 Jr. Oak Park, Ill. T 71 John Ferraro USC 6-4 240 So. Maywood, Calif. HOF T 75 Don Whitmire Navy 5-11 215 Jr. Decatur, Ala. HOF G 96 Bill Hackett Ohio State 5-10 191 Jr. London, Ohio G 63 Joe Stanowicz Army 6-1 215 Sr. Hackettstown, N.J. C 54 Jack Tavener Indiana 6-0 200 Sr. Granville, Ohio HOF B 35 Doc Blanchard Army 6-0 205 So. Bishopville, S.C. HOF B 41 Glenn Davis Army 5-9 170 So. Claremont, Calif. HOF B 55 Bob Fenimore Oklahoma A&M 6-2 188 So. Woodward, Okla. HOF B 22 Les Horvath Ohio State 5-10 167 Sr. Parma, Ohio HOF SECOND TEAM (11) E 74 Frank Bauman Purdue 6-3 209 Sr. Harvey, Ill. E 27 Phil Tinsley Georgia Tech 6-1 198 Sr. Bessemer, Ala. T 77 Milan Lazetich Michigan 6-1 200 So. Anaconda, Mont. T 99 Bill Willis Ohio State 6-2 199 Sr. Columbus, Ohio HOF G 75 Ben Chase Navy 6-1 195 Jr. San Diego, Calif. G 56 Ralph Serpico Illinois 5-7 215 So. Melrose Park, Ill. C 12 Tex Warrington Auburn 6-2 210 Jr. Dover, Del. B 23 Frank Broyles Georgia Tech 6-1 185 Jr. -

Valdosta State College Football 1982 VALDOSTA STATE COLLEGE FOOTBALL SCHEDULE 1982

Valdosta State College Football 1982 VALDOSTA STATE COLLEGE FOOTBALL SCHEDULE 1982 DATE OPPONENT SITE TIME Sept. 11 Mississippi College Clinton, Miss. 7 p.m. Sept. 18 Troy State Valdosta 7:30 p.m. Sept. 25 Georgia Southern Statesboro 1:30 p.m. Oct. 2 Central Florida Valdosta 7:30 p.m. Oct. 9 Delta State Cleveland, Miss. 7 p.m. Oct. 16 Jacksonville State Jacksonville, Ala. 7:30 p.m. Oct. 23 Albany State Albany, Ga. 1:30 p.m. Oct. 30 North Alabama Valdosta 7:30 p.m. Nov. 6 Kentucky State Frankfort, Ky. 1:30 p.m. Nov. 13 Livingston Valdosta 7:30 p.m. Nov. 20 Georgia Southern Valdosta 7:30 p.m. All Times Local Index General Athletic Director............................3 Information Coaches..................................... 4-8 Composite Schedule ...Back Cover Name: Valdosta State College Gulf South Conference............... 20 Location: Valdosta, Georgia Media Outlets..............Inside Back Founded: 1906 Memo To Media...........................32 Enrollment: 5000 Opponents..............................22-26 President: Dr. Hugh C. Bailey Outlook...........................................9 Colors: Red and Black Player Profiles........................10-17 Nickname: Blazers President........................................3 Stadium: Cleveland Field Records.................................. 27-31 Capacity: 11,738 Roster........................................... 18 Conference: Gulf South Staff Directory.............................32 Affiliation: NCAA, Division II Travel Plans................................... 9 Valdosta State College............... -

2019 Mercer Football

2019 MERCER FOOTBALL MercerBears.com l Twitter: @MercerFootball l Facebook: /MercerFootball l Instagram: @MercerFootball THE GAME MERCER BEARS (3-4, 2-2 SoCon) ► Mercer hits the road for another Southern Conference test Head Coach: Bobby Lamb (Furman, 1987) Saturday in Charleston - Mercer is 1-1 in road league games Career Record: 106-73 (16th Season), Record at Mercer: 39-35 (7th Season), Record vs. The Citadel: 7-7 this season. October 26, 2019 l 2 p.m. ET l Charleston, S.C. l Johnson Hagood Stadium (11,500) ► The game will be The Citadel's 2019 Homecoming Game. ►Bears running back Deondre Johnson has rushed for 6.20 THE CITADEL BULLDOGS (4-4, 2-2 SoCon) yards per carry this season, which ranks 17th best in the FCS Head Coach: Brent Thompson (Norwich, 1998) and third in the conference. Career Record: 24-18 (Fourth Season), Record at The Citadel: 24-18 (Fourth Season), Record vs. Mercer: 2-1 ► Senior lineman Dorian Kithcart has averaged 1.1 tackles TV: ESPN3 for loss per game this year, which ranks seventh in the SoCon. Talent: Kevin Fitzgerald (Play-by-Play) v Matt Dean (Analyst) v Emily Crevani (Sideline) ► Redshirt freshman kicker Caleb Dowden remains perfect Radio: Mercer Sports Network (100.9 The Creek FM & SportsMic) on field goal and extra-point attempts this season - one of Talent: Rick Cameron (Play-by-Play) v Roger Jackson (Analyst) v Charles Davis (Sideline) two players in the FCS. Live Stats: MercerBears.com Twitter: @MercerFootball Series History: CIT leads 10-5-1 Charleston: CIT leads, 4-3-1 MERCER BEARS Macon: CIT leads, 4-0 Neutral Sites: Teams tied, 2-2 Ranking -- (Coaches) / -- (STATS) First Meeting: The Citadel, 10-0, in Charleston, S.C. -

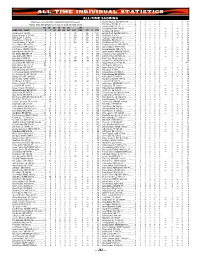

ALL-TIME Individual STATISTICS ALL-TIME SCORING Order Based on Total Points

ALL-TIME individual STATISTICS ALL-TIME SCORING Order based on total points. Updated through 2019 season. Boomer Esiason, QB 1984-92, 97 ............. 5 0 0 0 0 0 — 0 — 0 30 Players active with Bengals as of July 21, 2020 are listed in bold. Eric Kattus, TE 1986-91 ............................ 0 5 0 0 0 0 — 0 — 0 30 Jon Kitna, QB 2001-05 .............................. 5 0 0 0 0 0 — 0 — 0 30 TD- TD- TD- TD- TD- TD- 2-PT. Pat McInally, P/WR 1976-85...................... 0 5 0 0 0 0 — 0 — 0 30 NAME, POS., YEARS R P PR KR INT FR* PAT* CON. FG S PTS Ken Riley, CB 1969-83 .............................. 0 0 0 0 5 0 — 0 — 0 30 Jim Breech, K 1980-92 .............................. 0 0 0 0 0 0 476 0 225 0 1151 Bernard Scott, RB/KOR 2009-13 ............... 4 0 0 1 0 0 — 0 — 0 30 Shayne Graham, K 2003-09 ...................... 0 0 0 0 0 0 248 0 177 0 779 Clint Stitser, K 2010 ................................... 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 0 7 0 29 Mike Nugent, K 2010-16 ............................ 0 0 0 0 0 0 247 0 157 0 718 Virgil Carter, QB 1970-73 .......................... 4 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 — 0 25 Doug Pelfrey, K 1993-99 ............................ 0 0 0 0 0 0 201 0 153 0 660 Brian Milne, RB 1996-99 ........................... 4 0 0 0 0 0 — 1 — 0 26 Horst Muhlmann, K 1969-74 ...................... 0 0 0 0 0 0 189 0 120 0 549 Rex Burkhead, RB 2013-16 ...................... -

Player History, Continued)

(Player history, continued) PLAYER HISTORY — DRAFTS 1968 AFL EXPANSION DRAFT JAN. 21 1968 AFL/NFL DRAFT JAN. 30-31 1970 NFL DRAFT JAN. 27-28 PLAYER .................. POS. COLLEGE ........................... AFL TEAM RD. PLAYER ................... POS. COLLEGE ....................... SEL. # RD. PLAYER .................... POS. COLLEGE ....................... SEL. # Dan Archer* ...................... T Oregon ............................. Oakland Raiders 1 Bob Johnson....................... C Tennessee .................................. *2 1 Mike Reid ......................... DT Penn State .................................... 7 Estes Banks* .................. RB Colorado .......................... Oakland Raiders 1 (sent to Miami in trade on 12-26-67) ............................................ *27 2 Ron Carpenter .................. DT North Carolina State ................... 32 Joe Bellino ...................... RB Navy .................................. Boston Patriots 2a Bill Staley ....................... DE/T Utah State ................................. *28 3 Chip Bennett ..................... LB Abilene Christian ......................... 60 Jim Boudreaux ................ DT Louisiana Tech .................. Boston Patriots 2 (sent to Miami in trade on 12-26-67) ............................................ *54 4a Joe Stephens ..................... G Jackson State ............................. 85 Dan Brabham* ................ LB Arkansas .............................Houston Oilers 2b Tom Smiley....................... RB Lamar ....................................... -

Valdosta State University Fact Book 2016-2017

VSU Fact Book 2016-2017 Valdosta State University Fact Book 2016-2017 Office of Institutional Research i VSU Fact Book 2016-2017 Table of Contents Cover Page.............................................................................................................. Foreword......................................................................................................................................................... 1 General Information................................................................................................ 2 VSU Quick Facts ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Brief Chronology of VSU............................................................................................................................... 4 Concise Mission Statement......................................................................................................................... 5 Strategic Goals 2013-2019......................................................................................................................... 6 Board of Regents Membership................................................................................................................... 7 Board of Regents Organizational Chart.................................................................................................... 8 VSU Organizational Chart.......................................................................................................................... -

2021 Nfl Draft Notes

2021 NFL DRAFT NOTES NFL DRAFT FACTS AND FIGURES WHAT: 86th Annual National Football League Player Selection Meeting. WHERE: Cleveland, Ohio. WHEN: 8:00 PM ET, Thursday, April 29 (Round 1). 7:00 PM ET, Friday, April 30 (Rounds 2-3). Noon ET, Saturday, May 1 (Rounds 4-7). The first round will conclude on Thursday by approximately 11:45 PM ET. In 2020, the first round consumed three hours and 54 minutes. The second and third rounds will conclude on Friday by approximately 11:30 PM ET. The second and third rounds took a combined four hours and 49 minutes in 2020. The draft will conclude by approximately 7:00 PM ET on Saturday with the final four rounds. Rounds 4 through 7 took six hours and 57 minutes in 2020. ROUNDS: Seven Rounds – Round 1 on Thursday, April 29; Rounds 2 and 3 on Friday, April 30; and Rounds 4 through 7 on Saturday, May 1. There will be 259 selections, including 37 compensatory choices that have been awarded to 17 teams that suffered a net loss of certain quality unrestricted free agents last year. The following 37 compensatory choices will supplement the 222 regular choices in the seven rounds – Round 3: New England, 33; Los Angeles Chargers, 34; New Orleans, 35; Dallas, 36; Tennessee, 37; Detroit, 38; San Francisco, 39; Los Angeles Rams, 40; Baltimore, 41; New Orleans, 42. Round 4: Dallas, 33; New England, 34; Pittsburgh, 35; Los Angeles Rams, 36; Green Bay, 37; Minnesota, 38; Kansas City, 39. Round 5: New England, 33; Green Bay, 34; Dallas, 35; San Francisco, 36; Kansas City, 37; Atlanta, 38; Atlanta, 39; Baltimore, 40. -

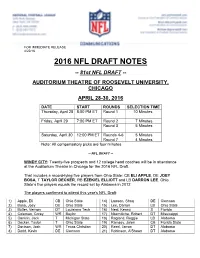

2016 Nfl Draft Notes

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 4/22/16 2016 NFL DRAFT NOTES -- 81st NFL DRAFT -- AUDITORIUM THEATRE OF ROOSEVELT UNIVERSITY, CHICAGO APRIL 28-30, 2016 DATE START ROUNDS SELECTION TIME Thursday, April 28 8:00 PM ET Round 1 10 Minutes Friday, April 29 7:00 PM ET Round 2 7 Minutes Round 3 5 Minutes Saturday, April 30 12:00 PM ET Rounds 4-6 5 Minutes Round 7 4 Minutes Note: All compensatory picks are four minutes -- NFL DRAFT -- WINDY CITY: Twenty-five prospects and 12 college head coaches will be in attendance at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago for the 2016 NFL Draft. That includes a record-tying five players from Ohio State: CB ELI APPLE, DE JOEY BOSA, T TAYLOR DECKER, RB EZEKIEL ELLIOTT and LB DARRON LEE. Ohio State’s five players equals the record set by Alabama in 2012. The players confirmed to attend this year’s NFL Draft: 1) Apple, Eli CB Ohio State 14) Lawson, Shaq DE Clemson 2) Bosa, Joey DE Ohio State 15) Lee, Darron LB Ohio State 3) Butler, Vernon DT Louisiana Tech 16) Neal, Keanu S Florida 4) Coleman, Corey WR Baylor 17) Nkemdiche, Robert DT Mississippi 5) Conklin, Jack T Michigan State 18) Ragland, Reggie LB Alabama 6) Decker, Taylor T Ohio State 19) Ramsey, Jalen CB Florida State 7) Doctson, Josh WR Texas Christian 20) Reed, Jarran DT Alabama 8) Dodd, Kevin DE Clemson 21) Robinson, A'Shawn DT Alabama 9) Elliott, Ezekiel RB Ohio State 22) Stanley, Ronnie T Notre Dame 10) Goff, Jared QB California 23) Treadwell, Laquon WR Mississippi 11) Hargreaves, Vernon CB Florida 24) Tunsil, Laremy T Mississippi 12) Jack, Myles LB UCLA 25) Wentz,