Grassroots Protest Movements and Political Indeterminacy in an Evolving Burma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Haut Commissariat Des Nations Unies Office of the United Nations Aux Droits De L’Homme High Commissioner for Human Rights

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT DES NATIONS UNIES OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS AUX DROITS DE L’HOMME HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS PROCEDURES SPECIALES DU SPECIAL PROCEDURES OF THE CONSEIL DES DROITS DE L’HOMME HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Mandates of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar; the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression; the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders; and the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment REFERENCE: UA G/SO 214 (67-17) Assembly & Association (2010-1) G/SO 214 (107-9) G/SO 214/62-11 G/SO 214 (53-24) MMR 12/2012 13 December 2012 Excellency, We have the honour to address you in our capacity as Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar; Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression; Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders; and Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment pursuant to Human Rights Council resolutions 19/21, 16/4, 15/21, 16/5, and 16/23. In this connection, we would like to draw the attention of your Excellency’s Government to information we have received regarding the arrest, detention and upcoming trial of prominent human rights defender Ashin Gambira (aka) Nyi Nyi Lwin. -

Flash Alert – Covid-19 Pandemic in Myanmar: Details on 2 October Cases Saturday, October 3, 2020

Flash alert – Covid-19 Pandemic in Myanmar: Details on 2 October Cases Saturday, October 3, 2020 Yesterday evening at 20:00 hrs, 1,142 new Covid-19 cases were identified in 24 hours, i.e. 15,151 cases since the beginning of the second wave on 16 August. Since the beginning of the pandemic in March, 15,525 people have been contaminated in Myanmar, and a total of 353 people have died of Covid-19. At 17:00 Hrs, the MoHS released the spatial breakdown of those 1,142 cases: 1046 in Yangon Region, 25 in Ayeyarwaddy Region, 22 in Mandalay Region, 16 in Sagaing Region, 9 in Rakhine State, 6 in Mon State, 5 in Bago Region, 5 in Naypyitaw Territory of Union, 4 in Shan State, 2 in Magway Region, 1 in Kachin State and 1 in Kayin State. Since 16 August, 11,671 cases have been reported in Yangon Region. The most significant surges took place in Hlaing Thar Yar Township (+136 cases) and Thingangyun Township (+106). Insein is the most-affected township in Yangon, ahead of Thingangyun, North Okkalapa, Mingaladon Townships, all counting more than 500 cases. Imported cases N° of total cases Township Local cases N° of new cases on 2 October from abroad since 16 August Ahlone 13 13 157 Bahan 24 24 229 Botahtaung 7 7 182 Dagon 6 6 199 Dagon Myothit (East) 11 11 228 Dagon Myothit (North) 7 7 254 Dagon Myothit (South) 11 11 253 Dagon Seikkan 11 11 167 Dala 9 9 360 Dawbon 8 8 176 Hlaing 1 20 21 398 FLASH 201003 – Covid-19 update: Details on 2 October Cases Imported cases N° of total cases Township Local cases N° of new cases on 2 October from abroad since 16 -

Flash Alert – Covid-19 Pandemic in Myanmar: Details on 24 Sept Evening and 25 Sept Morning Cases Friday, September 25, 2020

Flash alert – Covid-19 Pandemic in Myanmar: Details on 24 Sept Evening and 25 Sept Morning Cases Friday, September 25, 2020 As we reported in our previous flash alerts, 5161 new Covid-19 cases were identified yesterday evening at 20:00 Hrs and 171 new cases today at 08:00 Hrs, i.e. a total of 687 cases in 24 hours, the most massive 24-hour increase since the beginning of the pandemic. Since the beginning of the second Covid-19 wave on 16 August, 8,140 positive cases have been identified in Myanmar, i.e. 8,514 people since the beginning of the pandemic in March. Yesterday evening and today morning, 8 deaths were reported, and between this morning and this evening at 18:30, 17 more people died. In total, 172 people have died of Covid-19 since the beginning of the epidemic. At 17:00 Hrs, the MoHS released the spatial breakdown of those 687 cases: 572 in Yangon Region, 32 in Rakhine State, 30 in Ayeyarwaddy Region, 18 in Mandalay Region, 10 in Bago Region, 10 in Mon State, 8 in Sagaing Region, 3 in Thanintaryi Region, 2 in Nay Pyi Taw, 1 in Kayin State and 1 in Chin State. Since 16 August, 5,821 cases have been reported in Yangon Region. In the last 24 hours, the epidemic has surged in Thingangyun Township (+52 cases), Mayangon Township (+47 cases), Mingala Taungnyunt Township (+39 cases). Thingangyun, South and North Okkalapa, Tarmwe, Hlaing, Hlaing Thayar, Insein, Thaketa and Mingaladon Townships stand out as hotspots of the pandemic. -

Prevention of Blindness in Myanmar: Situation Analysis and Strategy For

Prevention of Blindness in Myanmar: Situation Analysis and Strategy for Change (Supported by International Agency for Prevention of Blindness and Standard Chartered Bank) Report Prepared by Gopal P. Pokharel, MD, MPH Mechi Eye Hospital Rohit Khanna, MD, MPH L V Prasad Eye Institute Submitted to International Agency for Prevention of Blindness (IAPB) and Standard Chartered Bank (SCB) Content Page No A. Acknowledgements 1 B. List of Acronyms 3 C. Executive Summary 5 D. Background 7 E. Situation Analysis 11 1. Blindness and Visual Impairment (VI) in Myanmar 11 2. Workload Estimate 13 3. National Plan for action for VISION 2020 14 4. Eye Care Infrastructure 14 5. Human Resource (HR) 17 6. Training 19 7. Service Delivery 18 8. Primary Health Care and Primary Eye Care 21 9. INGO services in Myanmar 22 10. Private Sector in Myanmar 24 11. SWOT 24 F. Recommendations 25 Annexure 1. Schedule for IAPB 2. Presentation: Situation Analysis: Eye Care in Myanmar 3. Presentation: Human Resources Development in Ophthalmology in Myanmar 4. Presentation: Helen Keller Eye Health Initiatives in Myanmar 5. Report: Myanmar Eye Care Program 1 A. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We extend our gratitude to the following members: No. Name Designation Department 1. Professor Than Cho Rector University of Medicine-1, Yangon. 2. Dr. Ngwe San Medical Superintendent Yangon Eye Hospital, Yangon. 3. Dr. Aye Ko Ko Regional Director Yangon Regional Health Department. 4. Professor Tin Win Professor/Head Department of Ophthalmology, Yangon Eye Hospital 5. Dr. Khin Nyein Lin Deputy Director Department of Health, (Trachoma Control and Nay Pyi Daw. Prevention of Blindness Program) 6. -

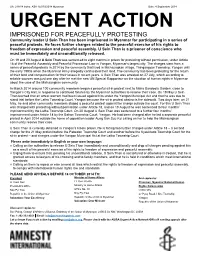

URGENT ACTION IMPRISONED for PEACEFULLY PROTESTING Community Leader U Sein Than Has Been Imprisoned in Myanmar for Participating in a Series of Peaceful Protests

UA: 218/14 Index: ASA 16/019/2014 Myanmar Date: 4 September 2014 URGENT ACTION IMPRISONED FOR PEACEFULLY PROTESTING Community leader U Sein Than has been imprisoned in Myanmar for participating in a series of peaceful protests. He faces further charges related to the peaceful exercise of his rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly. U Sein Than is a prisoner of conscience who must be immediately and unconditionally released. On 19 and 20 August U Sein Than was sentenced to eight months in prison for protesting without permission, under Article 18 of the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law in Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city. The charges stem from a series of peaceful protests in 2014 by the community that lived in Michaungkan village, Thingangyun Township, Yangon until the early 1990s when the Myanmar Army allegedly confiscated their land. The community has been protesting for the return of their land and compensation for their losses in recent years. U Sein Than was arrested on 27 July, which according to reliable sources was just one day after he met the new UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar about the case of the Michaungkan community. In March 2014 around 100 community members began a peaceful sit-in protest next to Maha Bandoola Garden, close to Yangon’s City Hall, in response to continued failures by the Myanmar authorities to resolve their case. On 19 May U Sein Than learned that an arrest warrant had been issued against him under the Yangon Municipal Act and that he was due to stand trial before the Latha Township Court, Yangon because the sit-in protest obstructs the sidewalk. -

No Store Name Region State/Province City District Address

No Store Name Region State/Province City District Address Contact No 1 SHOWROOM_O2 MAHARBANDOOLA (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION WESTERN DISTRICT(DOWNTOWN) KYAUKTADA TOWNSHIP NO.212, PANSODAN ST. (MIDDLE BLOCK), KYAWKTADAR TSP 09 420162256 2 SHOWROOM_O2 BAGO (MM) LOWER MYANMAR BAGO REGION BAGO DISTRICT BAGO TOWNSHIP SHIN SAW PU QUARTER, BAGO TSP 09 967681616 3 SHOW ROOM _O2 _(SULE) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION WESTERN DISTRICT(DOWNTOWN) KYAUKTADA TOWNSHIP NO.118, SULAY PAGODA RD, KYAUKTADAR TSP 09 454147773 4 SHOWROOM_MOBILE KING ZEWANA (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION EASTERN DISTRICT THINGANGYUN TOWNSHIP BLDG NO.38, ROOM B1, GROUND FL, LAYDAUNKAN ST, THINGANGYUN 09 955155994 5 SHOWROOM_M9_78ST(MM) UPPER MYANMAR MANDALAY REGION MANDALAY DISTRICT CHANAYETHAZAN TOWNSHIP NO.D3, 78 ST, BETWEEN 27 ST AND 28 ST, CHANAYETHARSAN TSP 09 977895028 6 SHOWROOM_M9 MAGWAY (MM) UPPER MYANMAR MAGWAY REGION MAGWAY DISTRICT MAGWAY TOWNSHIP MAGWAY TSP 09 977233181 7 SHOWROOM_M9_TAUNGYI (LANMADAW ROAD, TAUNGYIUPPER TSP) (MM) MYANMAR SHAN STATE TAUNGGYI DISTRICT TAUNGGYI TOWNSHIP LANMADAW ROAD, TAUNGYI TSP 09 977233182 8 SHOWROOM_M9 PYAY (MM) LOWER MYANMAR BAGO REGION PYAY DISTRICT PYAY TOWNSHIP LANMADAW ROAD, PYAY TSP 09 5376699 9 SHOWROOM_M9 MONYWA (MM), BOGYOKE ROAD, MONYWAUPPER TOWNSHIP MYANMAR SAGAING REGION MONYWA DISTRICT MONYWA TOWNSHIP BOGYOKE ROAD, MONYWA TSP. 09 977233179 10 SHOWROOM _O2_(BAK) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON REGION EASTERN DISTRICT BOTATAUNG TOWNSHIP BO AUNG KYAW ROAD, LOWER 09 428189521 11 SHOWROOM_EXCELLENT (YAYKYAW) (MM) LOWER MYANMAR YAGON -

DMA Approved Medical Doctors List2020.April-2021March.Xlsx

Appendix A List of DMA Approved Medical Doctors for 2020 Sr No. Name Medical Centre Subsidiary Clinic 7 Stars Medical Centre 001 Dr. Swe Setk No. 429/437, Merchant Road, (Corner of Theinphyu Road & Merchant Road) . Botahtaung Township, Yangon, 002 Dr. Nyi Nyi Shin Myanmar. Phone: 01-398165 003 Dr. Soe Lwin Asia Pacific Centre for Medical & Dental Care No.98(A), KabarAye Pagoda Road, Bahan Township, 004 Dr. Zaw Lin Yangon, Myanmar. 005 Dr. Myint Zaw Phone: 01-549152/ 01-553783/ 09-73216940 006 Dr. Moe Aung Kyaw Naing Asia Royal Cardiac & Medical Centre No.14, Baho Street, Sanchaung Township, Yangon, 007 Dr. Htay Htay Myanmar. 008 Dr. Tun Naing Zaw Phone: 01-538055/ 01-2304999 009 Dr. Lu Zaw* Aung Yadana Hospital ( * Shwe Inlay Medical Centre) No. 5/24, Thirigon Estate, Waizayantar Road, 16/2 Ward, 010 Dr. Min Zaw Tun** ( ** Rose Hill Hospital ) Thingankyun Township, Yangon, Myanmar. 011 Dr. Maung Maung Khin Phone: 01-561878/ 01-573631/ 01-573632 Bo Aung Kyaw Healthy Screening Centre No. 106(B), Bo Aung Kyaw Street, G-F, Botahtaung 012 Dr. Zin Maung Thant Township, Yangon, Myanmar. Phone: 09-448021641 Note: * The said doctor is also available at the subsidiary clinic shown in the next column. Page 2 of 6 Sr No. Name Medical Centre Subsidiary Clinic Ca Mar Kyi Specialist Clinic and Diagnostic Centre 013 Dr. Hla Myint* No.111/3, Than Thu Mar Road, Thuwana 29 ward, (Lin Yaung Chi Healthcare and Medical Thingangyun Township,Yangon, Myanmar. Diagnostic Centre) 014 Dr. Kyi Phyu Aye Phone : 09-421078580/ 01-7330032/ 01-7333996 Email : [email protected] Chan Myae Myitta Hospital Dr. -

Public Awareness, Attitude and Understanding Toward Epilepsy Among Myanmar People

Neurol J Southeast Asia 2002; 7 : 81 – 88 Public awareness, attitude and understanding toward epilepsy among Myanmar people Nwe Nwe Win MMedSc MRCP, *Chit Soe MMedSc MRCP Department of Medicine, No (2) Military Hospital, Yangon; *Department of Medicine, Institute of Medicine (2), Yangon, Myanmar Abstract Objectives: To determine the public awareness, attitude and understanding among Myanmar people toward epilepsy and to compare this with similar surveys in the region. Methods: The survey was conducted in Yangon (urban), Hlegu, Taikyi and Ngaputaw (rural), Myanmar in 2002. Results: Of the 296 respondents, 82% had read or heard about epilepsy, 78% had seen a seizure and 25% knew someone with epilepsy. Forty-four percent objected to their children associating with epilepsy sufferers, 71% objected to their children marrying an epilepsy sufferer, 86% thought that persons with epilepsy should not be employed in jobs, 74% objected to employing an epilepsy sufferer even though the seizure did not interfere with his job, and 25% thought that epilepsy was insanity. As in surveys from other countries, there was low awareness of non-convulsive form of epilepsy. Only 33% identified epilepsy as a brain disease or disorder. As for treatment, 74% recommended Western medicine while 46% advocated prayer. Conclusion: The survey in Myanmar consisting of urban and rural areas showed that most respondents were aware of epilepsy but many had negative attitude towards persons with epilepsy, and poor understanding of its cause and treatment. INTRODUCTION Public awareness, attitude and understanding conducted among visitors to in-patients, toward epilepsy have been studied in the United outpatients, hospital staffs from two hospitals States1, the Federal Republic of Germany2, and private clinics. -

Chapter 10 Project Cost Estimates

The Preparatory Survey for The Project for Construction of Bago River Bridge Final Report Chapter 10 Project Cost Estimates The Preparatory Survey for The Project for Construction of Bago River Bridge Final Report 10. Project Cost Estimates 10.1 General Conditions (1) Method of Cost Estimation The estimation of project cost for the construction of Bago River Bridge is based on the results of the preliminary design of this Preparatory Survey and rough quantity estimation of work items. Financing for the 100% of eligible portion of the Project is assumed to be funded through the JICA loan scheme. As for the non-eligible portion, it is assumed that the state budget of the Government of Myanmar (GOM) will be allocated. (2) Conditions of Cost Estimation The conditions of cost estimation as instructed by JICA are shown in Table 10.1. Table 10.1 Conditions of Cost Estimation Item Condition Note Date of Estimate December 2013 Currency Foreign Currency: US dollar (USD), Japanese yen (JPY) Local Currency: Myanmar kyat (MMK) Exchange Rate USD 1=JPY 99.7 3 months average USD 1= MMK 975.0 rate Price Escalation Rate Foreign Currency Portion: 1.3%, Local Currency Portion: 3.7% Physical Contingency 5% Interest During Construction Construction Cost: 0.01% Consultant Fee: 0.01% Commitment Charge 0% Source: JICA Survey Team 10.2 Procurement (1) Procurement Conditions 1) Labor Major bridge projects in Myanmar have been executed by the Public Works itself. Design, construction, and supervision are conducted by the staff of Public Works. On the other hand, private construction companies in Myanmar have conducted the road construction works through the BOT scheme. -

Crackdown RIGHTS Repression of the 2007 Popular Protests in Burma WATCH December 2007 Volume 19, No

Burma HUMAN Crackdown RIGHTS Repression of the 2007 Popular Protests in Burma WATCH December 2007 Volume 19, No. 18(C) Crackdown Repression of the 2007 Popular Protests in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Map of Rangoon.......................................................................................................2 Map of Downtown Rangoon......................................................................................3 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 II. Crackdown After Crackdown: 45 Years of Military Rule ....................................... 15 Burma’s Economy: Poverty and Price Rises Spark Protests ................................ 21 III. Price Hikes, Peaceful Protests, and the Initial Reaction of the Authorities.........23 IV. The Monks Join the Protests............................................................................. 28 “Overturning of the Bowls”: The Monks’ Decision to Boycott the SPDC .............. 31 The Monks March in Rangoon ...........................................................................33 September 17 ..............................................................................................33 September 18..............................................................................................33 September 19 ..............................................................................................36 -

Myanmar Situation Update (28 June - 4 July 2021)

Myanmar Situation Update (28 June - 4 July 2021) Summary Myanmar ousted leader Aung San Suu Kyi appeared in the special court in Naypyitaw on 29 June and the court accepted the two evidence documents submitted by the junta for the case charged under Section 505(b) to incite unrest in the country although the lawyers of Aung San Suu Kyi objected. Those two documents are NLD party statements issued on 7 and 13 of February after the NLD’s leaders have been detained. Her lawyer also expects the trial will run longer than scheduled, with the prosecution still to call nearly two dozen witnesses. The junta has been building strong high-tech surveillance tools that can be used for internal repression, many of which come from Western companies. An investigation conducted by the “Lighthouse Reports” revealed that those technologies include high tech software that can extract data from different devices and surveillance over the internet. More than 50,000 Karen people have been displaced since the beginning of the year. Local community groups expect that there is much more the international community can do to help as humanitarian as is not enough meeting the survival of the people who fled their villages and living in makeshift shelters. Indian media also reported that over 700 people from Myanmar, mostly civilians, have entered Mizoram in the past few weeks. Altogether 10,025 Myanmar nationals have so far sneaked into Mizoram following the military coup. Media also reported that the Myanmar military shells struck Magar Yang camp, home to over 1,600 internally displaced persons in Kachin State, along the China border. -

46390-003: Power Distribution Improvement Project

Environmental and Social Monitoring Report #5th Semi-Annual Report 31 December 2018 Project No. 46390-003, Loan 3084 MYA: Power Distribution Improvement Project Prepared by Yangon Electricity Supply Enterprise (YESC) through the Ministry of Electricity and Energy (MOEE) of the Union of the Myanmar Republic and the Asian Development Bank. This Environmental and Social Monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or área. 1 | P a g e The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Electricity and Energy Yangon Electricity Supply Corporation Power Distribution Improvement Project Loan No: 3084-MYA (SF) Semi-annually Social Monitoring Report July-December 2018 Region : Yangon (Area 1) 2 | P a g e Contents Contents .............................................................................................................................. 3 Scope ..................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction and Project Characteristics ..................................................................... 4 1.1 Background ..................................................................................................