Author's Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

NVS 12-1-13-Announcements-Page;

Announcements: CFPs, conference notices, & current & forthcoming projects and publications of interest to neo-Victorian scholars (compiled by the NVS Assistant Editors) ***** CFPs: Journals, Special Issues & Collections (Entries that are only listed, without full details, were highlighted in a previous issue of NVS. Entries are listed in order of abstract/submission deadlines.) Penny Dreadfuls and the Gothic Edited Collection Abstracts due: 18 December 2020 Articles due: 30 April 2021 Famed for their scandalous content and supposed pernicious influence on a young readership, it is little wonder why the Victorian penny dreadful was derided by critics and, in many cases, censored or banned. These serialised texts, published between the 1830s until their eventual decline in the 1860s, were enormously popular, particularly with working-class readers. Neglecting these texts from Gothic literary criticism creates a vacuum of working-class Gothic texts which have, in many cases, cultural, literary and socio-political significance. This collection aims to redress this imbalance and critically assess these crucial works of literature. While some of these penny texts (i.e. String of Pearls, Mysteries of London, and Varney the Vampyre to name a few) are popularised and affiliated with the Gothic genre, many penny bloods and dreadfuls are obscured by these more notable texts. As well as these traditional pennys produced by such prolific authors as James Malcolm Rymer, Thomas Peckett Press, and George William MacArthur Reynolds, the objective of this collection is to bring the lesser-researched, and forgotten, texts from neglected authors into scholarly conversation with the Gothic tradition and their mainstream relations. This call for papers requests essays that explore these ephemeral and obscure texts in relevance to the Gothic mode and genre. -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

Historical Mysteries UK

Gaslight Books Catalogue 3: Historical Mysteries set in the UK Email orders to [email protected] Mail: G.Lovett, PO Box 88, Erindale Centre, ACT 2903 All prices are in Australian dollars and are GST-free. Postage & insurance is extra at cost. Orders over $100 to $199 from this catalogue or combining any titles from any of our catalogues will be sent within Australia for a flat fee of $10. Orders over $200 will be sent post free within Australia. Payment can be made by bank transfer, PayPal or bank/personal cheque in Australian dollars. To order please email the catalogue item numbers and/or titles to Gaslight Books. Bank deposit/PayPal details will be supplied with invoice. Books are sent via Australia Post with tracking. However please let me know if you would like extra insurance cover. Thanks. Gayle Lovett ABN 30 925 379 292 THIS CATALOGUE features first editions of mysteries set in the United Kingdom roughly prior to World War II. Most books are from my own collection. I have listed any faults. A very common fault is browning of the paper used by one major publisher, which seems inevitable with most of their titles. Otherwise, unless stated, I would class most of the books as near fine in near fine dustcover and are first printings and not price-clipped. (Jan 27, 2015) ALEXANDER, BRUCE (Bruce Alexander Cook 1932-2003) Blind Justice: A Sir John Fielding Mystery (First Edition) 1994 $25 Hardcover Falsely charged with theft in 1768 London, thirteen-year-old Jeremy Proctor finds his only hope in Sir John Fielding, the founder of the Bow Street Runners police force, who recruits young Jeremy in his mission to fight crime. -

Univerza V Mariboru

UNIVERZA V MARIBORU FILOZOFSKA FAKULTETA ODDELEK ZA ANGLISTIKO IN AMERIKANISTIKO DIPLOMSKO DELO STANKA RADOVIĆ MARIBOR, 2013 UNIVERZA V MARIBORU FILOZOFSKA FAKULTETA ODDELEK ZA ANGLISTIKO IN AMERIKANISTIKO Stanka Radović PRIMERJALNA ANALIZA FILMA “IGRA SENC” IN KNJIGE “BASKERVILLSKI PES” Diplomsko delo Mentor: red. prof. dr. Victor Kennedy MARIBOR, 2013 UNIVERSITY OF MARIBOR FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND AMERICAN STUDIES Stanka Radović A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF “A GAME OF SHADOWS” WITH THE BOOK “THE HOUND OF THE BASKERSVILLES” Diplomsko delo MENTOR: red. prof. dr. Victor Kennedy MARIBOR, 2013 I would like to thank my mentor, dr. Victor Kennedy for his support, help and expert advice on my diploma. I would like to thank my parents for their support, for all the sacrifices in their lives and for believing in me and being there for me all the time. POVZETEK RADOVIĆ, S.: Primerjalna analiza filma in knjige: A game of Shadow in The Hound of the Baskervilles. Diplomsko delo, Univerza v Mariboru, Filozofska fakulteta, Oddelek za anglistiko in amerikanistiko, 2013. V diplomski nalogi z naslovom Primerjalna analiza filma Igra senc in knjige Baskervillski pes je govora o deduktivnem načinu razmišljanja in o njegovem opazovanju, ki ga je v delih uporabljal Sherlock Holmes. Obravnavano je tudi vprašanje, zakaj je Sherlock Holmes še vedno tako priljubljen. Beseda teče tudi o življenju v viktorijanski Angliji. Osrednja tema diplomskega dela je primerjava filma in knjige. Predstavljene so vse podobnosti in razlike obeh del. Ključne besede: Sherlock Holmes, deduktivni način razmišljanja in opazovanja, viktorijanska Anglija ABSTRACT RADOVIĆ, S.: A Comparative analysis of “A Game of Shadow” with the book “The Hound of the Baskervilles”. -

Writer's Guide to the World of Mary Russell

Information for the Writer of Mary Russell Fan Fiction Or What Every Writer needs to know about the world of Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes as written by Laurie R. King in what is known as The Kanon By: Alice “…the girl with the strawberry curls” **Spoiler Alert: This document covers all nine of the Russell books currently in print, and discloses information from the latest memoir, “The Language of Bees.” The Kanon BEEK – The Beekeeper’s Apprentice MREG – A Monstrous Regiment of Women LETT – A Letter of Mary MOOR – The Moor OJER – O Jerusalem JUST – Justice Hall GAME – The Game LOCK – Locked Rooms LANG – The Language of Bees GOTH – The God of the Hive Please note any references to the stories about Sherlock Holmes published by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (known as The Canon) will be in italics. The Time-line of the Books BEEK – Early April 1915 to August of 1919 when Holmes invites the recovering Russell to accompany him to France and Italy for six weeks, to return before the beginning of the Michaelmas Term in Oxford (late Sept.) MREG – December 26, 1920 to February 6, 1921 although the postscript takes us six to eight weeks later, and then several months after that with two conversations. LETT – August 14, 1923 to September 8, 1923 MOOR – No specific dates given but soon after LETT ends, so sometime the end of September or early October 1923 to early November 1923. We know that Russell and Holmes arrived back at the cottage on Nov. 5, 1923. OJER – From the final week of December 1918 until approx. -

Constructing Coherence in the Holmesian Canon

The Final Problem: Constructing Coherence in the Holmesian Canon CAMILLA ULLELAND HOEL Abstract: The death and resurrection of Sherlock Holmes, a contrarian reading in which Holmes helps the murderer, and the century-long tradition of the Holmesian Great Game with its pseudo-scholarly readings in light of an ironic conviction that Holmes is real and Arthur Conan Doyle merely John Watson’s literary agent. This paper relies on these events in the afterlife of Sherlock Holmes in order to trace an outline of the author function as it applies to the particular case of Doyle as the author of the Sherlock Holmes stories. The operations of the author function can be hard to identify in the encounter with the apparently natural unity of the individual work, but these disturbances at the edges of the function make its effects more readily apparent. This article takes as its starting point the apparently strong author figure of the Holmesian Great Game, in which “the canon” is delineated from “apocrypha” in pseudo-religious vocabulary. It argues that while readers willingly discard provisional readings in the face of an incompatible authorial text, the sanctioning authority of the author functions merely as a boundary for interpretation, not as a personal-biographical control over the interpretation itself. On the contrary, the consciously “writerly” reading of the text serves to reinforce the reliance on the text as it is encountered. The clear separation of canon from apocrypha, with the attendant reinforced author function, may have laid the ground not only for the acceptance of contrarian reading, but also for the creation of apocryphal writings like pastiche and fan fiction. -

Olivia Votava Undergraduate Murder, Mystery, and Serial Magazines: the Evolution of Detective Stories to Tales of International Crime

Olivia Votava Undergraduate Murder, Mystery, and Serial Magazines: The Evolution of Detective Stories to Tales of International Crime My greatly adored collection of short stories, novels, and commentary began at my local library one day long ago when I picked out C is for Corpse to listen to on a long car journey. Not long after I began purchasing books from this series starting with A is for Alibi and eventually progressing to J is for Judgement. This was my introduction to the detective story, a fascinating genre that I can’t get enough of. Last semester I took Duke’s Detective Story class, and I must say I think I may be slightly obsessed with detective stories now. This class showed me the wide variety of crime fiction from traditional Golden Age classics and hard-boiled stories to the eventual incorporation of noir and crime dramas. A simple final assignment of writing our own murder mystery where we “killed” the professor turned into so much more, dialing up my interest in detective stories even further. I'm continuing to write more short stories, and I hope to one day submit them to Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine and be published. To go from reading Ellery Queen, to learning about how Ellery Queen progressed the industry, to being inspired to publish in their magazine is an incredible journey that makes me want to read more detective novels in hopes that my storytelling abilities will greatly improve. Prior to my detective story class, I was most familiar with crime dramas often adapted to television (Rizzoli & Isles, Bones, Haven). -

A Mary Russell Companion

AA MMaarryy RRuusssseellll CCoommppaanniioonn Exploring the World of Laurie R. King’s Mary Russell/Sherlock Holmes Series elcome to the world of Mary Russell, one-time apprentice, long-time partner to Sherlock Holmes. What follows is an introduction to Russell’s memoirs, published under the name of Laurie R. King beginning with The Beekeeper’s Apprentice in 1994. We’ve added comments, excerpts, illuminating photos and an assortment of interesting links and extras. Some of them are fun, some of them are scholarly. Which only goes to prove that laughter and learning can go hand in hand. Enjoy! Laurie R. King Laurie R. King.com Mary Russell.com Contents INTRODUCTION ONE: Beginnings: Mary stumbles (literally) on Holmes (The Beekeepers Apprentice) TWO: Coming of Age: A Balancing Act (A Monstrous Regiment of Women) THREE: Mary Russell, Theologian (A Letter of Mary) FOUR: Russell & Holmes in Baskerville Country (The Moor) FIVE: Time and Place in Palestine (O Jerusalem) SIX: The Great War & the Long Week-end (Justice Hall) SEVEN: An Empire in Sunset—The Raj, Kipling’s Boy, & the Great Game (The Game) EIGHT: Loose Ends—Russell & Holmes in America (Locked Rooms) NINE: A Face from the Past (The Language of Bees) TEN: Russell & Holmes Meet a God (The God of the Hive) POSTSCRIPT One: Mary stumbles (literally) on Holmes Click cover for book page The Beekeeper‘s Apprentice: With Some Notes Upon the Segregation of the Queen (One of the Independent Mystery Booksellers Association’s 100 Best Novels of the Century) Mary Russell is what Sherlock Holmes would look like if Holmes, the Victorian detective, were a) a woman, b) of the Twentieth century, and c) interested in theology. -

A Snapshot of Sherlock Holmes and the Stories That Made Him Famous

Chapter 1 A Snapshot of Sherlock Holmes and the Stories That Made Him Famous In This Chapter ▶ Debunking the erroneous popular image of Sherlock Holmes ▶ Tracing Holmes the creation and Doyle the creator ▶ Reviewing all the stories that comprise the Holmes canon ▶ Looking at Holmes’s enduring popularity ry this experiment: Ask ten random people if they know who Sherlock THolmes is. Odds are they’ll say yes. Then ask what they know about him. Chances are they’ll say he’s a detective, he has a friend named Watson, he smokes a pipe, and he wears a funny hat. Some will even think he was real. What’s even more amazing is that if you were to try this experiment on every continent on the planet, you’d likely get the same results, demonstrating the grip that Sherlock Holmes has on the popular culture, even to this day. Sherlock Holmes:COPYRIGHTED Not Who MATERIAL You Think He Is The popular image of Sherlock Holmes is largely made up of clichés that have become associated with the Great Detective over the years. Some of these do come from the actual character as written in the stories, while others have come from the countless adaptations on TV and in the movies. But if you’re approaching the Holmes stories for the first time, you may be surprised at the person you find. Sherlock Holmes is not who you think he is. (And neither is his friend, Dr. Watson!) 005_484449-ch01.indd5_484449-ch01.indd 9 22/11/10/11/10 99:27:27 PMPM 10 Part I: Elementary Beginnings and Background Pop culture portrayal versus portrayal in the stories The common picture of Holmes is of a square-jawed, well-off, middle-aged, stuffy do-gooder who lives with an elderly, slightly befuddled roommate in a quaint London apartment. -

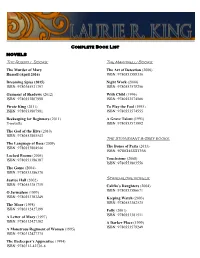

Complete Book List

Complete Book List NOVELS The Russell Books: The Martinelli Books: The Murder of Mary The Art of Detection (2006) Russell (April 2016) ISBN: 9780553588330 Dreaming Spies (2015) Night Work (2000) ISBN: 9780345531797 ISBN: 9780553578256 Garment of Shadows (2012) With Child (1996) ISBN: 9780553807998 ISBN: 9780553574586 Pirate King (2011) To Play the Fool (1995) ISBN: 9780553807981 ISBN: 9780553574555 Beekeeping for Beginners (2011) A Grave Talent (1993) E-novella ISBN: 9780553573992 The God of the Hive (2010) ISBN: 9780553805543 The Stuyvesant & Grey books: The Language of Bees (2009) ISBN: 9780553804546 The Bones of Paris (2013) ISBN: 9780345531766 Locked Rooms (2005) ISBN: 9780553386387 Touchstone (2008) ISBN: 9780553803556 The Game (2004) ISBN: 9780553386370 Stand-alone novels: Justice Hall (2002) ISBN: 9780553381719 Califia’s Daughters (2004) ISBN: 9780553586671 O Jerusalem (1999) ISBN: 9780553383249 Keeping Watch (2003) ISBN: 9780553382525 The Moor (1998) ISBN: 9780312427399 Folly (2001) A Letter of Mary (1997) ISBN: 9780553381511 ISBN: 9780312427382 A Darker Place (1999) ISBN: 9780553578249 A Monstrous Regiment of Women (1995) ISBN: 9780312427375 The Beekeeper’s Apprentice (1994) ISBN: 9780312-42736-8 Complete Book List Anthology Contributions NONFICTION Co-editor, In the Company of Sherlock Holmes, with Not in Kansas Anymore, TOTO, co-authored with Leslie S. Klinger, Pegasus (2014) ISBN: 1605986585 Barbara Peters (2015), Poisoned Pen Press Co-editor, A Study in Sherlock, with Leslie S. Klinger, Crime & Thriller Writing: A Writers’ & Artists’ Random House & Poisoned Pen Press (2011) ISBN: Companion, co-authored with Michelle Spring (2013) 9780345529930 ISBN: 9781472523938 “Hellbender” in Down These Strange Streets, ed. My Bookstore, ed. Ronald Rice, Black Dog & George R. R. Martin & Gardner Dozois, Ace Hardcover Levanthal (2012) (2011) ISBN: 9780441020744 ISBN: 9781579129101 Introduction, The Grand Game, Volume 1, The Baker Books to Die For, ed. -

Information for the Writer of Mary Russell Fan Fiction Or What Every Writer Needs to Know About the World of Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes As Written by Laurie R

Information for the Writer of Mary Russell Fan Fiction Or What Every Writer needs to know about the world of Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes as written by Laurie R. King in what is known as The Kanon By: Alice “…the girl with the strawberry curls” **Spoiler Alert: This document covers all eleven of the Russell books currently in print. The Kanon BEEK – The Beekeeper’s Apprentice ** MREG – A Monstrous Regiment of Women LETT – A Letter of Mary MOOR – The Moor OJER – O Jerusalem JUST – Justice Hall GAME – The Game LOCK – Locked Rooms LANG – The Language of Bees GOTH – The God of the Hive PIRA – The Pirate King GARM – Garment of Shadows **B4B – Beekeeping for Beginners, an e-novella (Told from Holmes’ POV this short story covers the meeting and early weeks of the friendship between Holmes and Russell) Please note any references to the stories about Sherlock Holmes published by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (known as The Canon) will be in italics. The Time-line of the Books BEEK – Early April 1915 to August of 1919 when Holmes invites the recovering Russell to accompany him to France and Italy for six weeks, to return before the beginning of the Michaelmas Term in Oxford (late Sept.) MREG – December 26, 1920 to February 6, 1921 although the postscript takes us six to eight weeks later, and then several months after that with two conversations. LETT – August 14, 1923 to September 8, 1923 MOOR – No specific dates given but soon after LETT ends, so sometime the end of September or early October 1923 to early November 1923.