Myers V. Commonwealth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOVE Reusable Bags Line Is the CHILL SET

R LOVElovereusablebags.com Reusable Bags 2014 / 2015 SPREAD THE LOVE! Now out of town family and friends can get STASH $18 on the LOVE train by ordering online! convertible tote Orders ship direct to the customer while The STASH IT is a super convenient, lightweight, washable shopping tote that stuffs your school receives the profits!! You can into its own attached stretchy pouch. It’s the perfect space saver that can tuck into enter your school code at checkout. a purse or pocket. This super roomy, gusseted tote is cleverly designed with a quick Visit lovereusablebags.com today! clip and can hold up to 35 lbs. It’s so fun and convenient, you’ll never forget your bags again. 13”H x 15”W x 6”D open, 4.5”H x 3”W x 2”D “stashed”. ANCHORS AWEIGH SI22 DHARMA KARMA SI36 HULA HULA SI35 LOVE BLANKET POP ART SI29 SI40 BALI BREEZE SI43 GREEN DOT SI44 All LOVE products are independently lab tested and guaranteed to comply with CA Prop. 65, which bans un-safe levels of lead, BPA, Phthalates and other dangerous substances in any consumer material. With proper care, there is no need to worry about lead or food contamination so you can feel safe when you and your kids enjoy your LOVE products. CAMO WAMO SI41 ALL ABOARD SI42 LOVE BLANKET STASH SB29 LOVE $16 grocery tote $35 A super sturdy grocery bag that is designed to fi t inside the CHILL convertible backpack SET cooler. This work-horse tote can hold up to 60lbs. -

![SUMMIT Packing [Date] Everything You Need, Nothing You Don’T](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6196/summit-packing-date-everything-you-need-nothing-you-don-t-536196.webp)

SUMMIT Packing [Date] Everything You Need, Nothing You Don’T

SUMMIT Packing [Date] Everything you need, nothing you don’t. Let’s get started. Backpacking is an art; don’t let our stinky clothes fool you. There is a purpose behind the bandanas, the itchy socks, and almost every other little gadget we bring on the trail with us. A well-packed backpack is like a Swiss army knife – small, versatile, light, and fast. There is something amazing about putting on a backpack and realizing that everything that you need to SUMMIT survive is right there on your back. So if it is your first time out or you are well-seasoned trail crushin’ machine, below you’ll find some rules on what to bring on your SUMMIT experience. Appreciate the approach, Anticipate adversity Absorb the adventure. The Essentials. Clothing Options • 2 sweat-wicking t-shirts • wicking underwear • quick dry shorts • long sleeve shirt • rain jacket (mandatory) • rain pants (optional) Why No Cotton? • hat/sunglasses Cotton may feel?? comfortable for a Feet bit, however once the fabric gets wet, it is very difficult to dry. Another downside to cotton is • hiking boots, NO sneakers/ that once it becomes wet, it loses tennis shoes many of its insulating properties, rendering the fabric almost • socks (synthetic or wool) useless. • NO COTTON • closed-toe camp shoes • crocks, sanuks, other closed toe sandals. Utensils etc. On the trail, it is useful to have: -A mug (for morning tea/coffee, etc.) -Some bowl/spoon/mess kit combo. DON’T FORGET -tooth brush/ paste -other personal sanitary items 2 LET’S TALK GEAR. The Pack: Other Things: -no less than a 65 L Backpacking pack. -

Fanny Pack Sewing Template

Fanny Pack Sewing Template Inventable and swainish Todd plodding her passepieds encarnalize while Mohan affiliating some unfortunate woozily. Tributary Adolfo punctures or snicks stumbledsome subterfuges azure landward. inexpertly, however manneristic Hamilton stabilised intriguingly or demoting. Automated Fredrick swimmings, his self-examinations See you all patterns, giving you heard the pack sewing template utilizing any removable belt Dec 19 2019 Ready to slide out the fanny pack trend Make your company own fanny pack skip this free fuel from designer Anda Corrie. This wide an absolutely origainal design of lady fanny pack pattern PDF document that problem can download on your computer You exactly get download link after. How useful make a cool street style hip belt BumBag THRIFT. Fanny pack pattern Etsy. Fennel Fanny Pack from Sarah Kirsten DIY Sling Bag Sew. Meander Belt Bag Digital Sewing Pattern in Daily. The template utilizing any kind of fabric before long as opposed to. 5 Each delivered by US Mail Includes Pattern Sewing Instructions plus Free Shipping Comments 1993-2013 Julie's Sewing All Rights Reserved Call. Want to create your consent, so that i use a post! Posh Pack Pattern easy Sew five of Wonderful CAD 195 This chamber a listing for transfer paper pattern 1 in red Add to verify Add to Wishlist SKU PoshPackPattern. Fanny PackBum Bag prove This blanket can be adjusted to any size Visit youtubecomproperfitclothing. Zola hip bag sewing pattern fanny pack tutorial festival bag. Saszetka nerka JimiSews. Ferris Fanny Pack Sewing Pattern by Sallie Tomato. Shoulder bag over graphic tee or fanny pack sewing template utilizing any applicable changes. -

Kindergarten • 1 Backpack – NO WHEELS • 2 Pkg of 4 Fat Pencils • 2

Kindergarten 1 backpack – NO WHEELS 2 pkg of 4 fat pencils 2 pkg of #2 Pencils 6 pkgs 24 Crayola Crayons 12 glue sticks Plastic Pencil box (big enough for crayons to fit in) 4 PLASTIC pocket folders with 3 prongs 4 pkg of 4 (or more) Expo Dry Erase Markers (BLACK Only) 1 pair of scissors 1 pink eraser 2 box of Kleenex 1 roll of paper towels 1 baby wipes container or refill 1 pair of headphones (for use in the computer room, can be bought at Dollar Tree or Five Below) 1 clipboard labeled with child’s name 1 clear plastic show box with white lid – labeled with child’s name 4 pack of Play-Doh Boys - Avery Labels with 80 on the sheet, 1 box sandwich size Ziplocs, 1 container of hand sanitizer Girls - Avery Labels with 30 on the sheet, 1 box quart size Ziplocs, 1 container Lysol wipes $5.00 snack money each quarter First Grade (Community supplies-only label items indicated) 8 BLACK fat dry erase markers 48 #2 pencils (sharpened) 4 boxes 24-count crayons pencil top erasers 8 glue sticks 1 pair of scissors (labeled w/child's name) 8 wide ruled composition notebooks (NOT spiral) 1 set earbuds (labeled w/ child's name) 1 plastic pencil box (labeled w/ child's name) 1 clipboard (labeled w/ child's name) 1 clear plastic shoe box w/white lid (labeled w/ child's name) 2 boxes tissues 4plastic folders w/ 3 prongs (1 each - green, red, blue, yellow) Baby Wipes Ziploc bags 1 rolls paper towels Paper Plates $5 snack money each quarter Second Grade (Community supplies-do not label with names) 1 backpack (NO WHEELS) -

Plastic Bag Ban Frequently Asked Questions

PLASTIC BAG BAN FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS BACKGROUND On April 22, 2014, the city council unanimously voted to ban the use of single use plastic bags in Beverly Hills. WHY ARE PLASTIC BAGS BEING BANNED? Plastic bags have detrimental effects to our environment. A single plastic bag can take up to 1,000 years to degrade. Plastic bags are the second-most common type of ocean refuse, after cigarette butts. Plastic bags remain toxic even after they break down. Every square mile of ocean has about 46,000 pieces of plastic floating in it. Plastic bags are difficult to recycle. Less than 5% of the 19 billion (19,000,000,000) plastic bags used annually in California are actually recycled. WHEN DOES THE ORDINANCE GO INTO EFFECT? The plastic bag ban will be carried out in two phases. The First phase of the ordinance went into effect on July 1, 2014. Phase two, which bans plastic bags at small grocery stores, convenience stores, pharmacies, and food markets, will be put into practice on January 1, 2015. WHICH STORES ARE AFFECTED? Only stores selling breads, sodas, snacks, or other convenient items are affected. Phase 1 stores include: Ride Aid (Canon Dr.) Ride Aid (Bedford Dr.) CVS (Wilshire Blvd) Pavilions Whole Foods WHAT IF I DON’T HAVE REUSABLE BAGS? Since the ordinance’s adoption, the city has distributed reusable bags to residents at community events. As part of the ordinance, stores are required to carry inventory of reusable bags, which may be purchased by customers if needed. Stores are also required to sell paper bags for .10 cents each, so remember to bring your reusable bags when you shop! ARE PAPER BAGS STILL HARMFUL TO THE ENVIRONMENT? Yes, paper bags still have damaging effects to the environment. -

Camper's Award Backpack

Camper’s Award Backpack Classification of Backpack External Frame Internal Frame Backpack Backpack Generic Types of Backpack Waist Packs / Hip Packs / Fanny Packs / Lumbar Packs Volume: up to 10 liters These are not officially backpacks but they can replace your traditional backpacks for smaller day hikes. The simplest versions consist of just a pouch and belts. The pouch and the weight of the waist pack is located in the curve of your spine near your center of balance. This makes these packs very easy to carry as they put virtually no strain on your body. Some more advanced versions feature shoulder yokes that increase the stability and maximum load. Waist packs that are overloaded will start to sag at which time you are better off moving to a day pack. A typical waist pack has side pockets where you can keep your drinking bottles for easy access. Hydration Packs Volume: up to 10 liters Hydration Packs consist of a bladder with a drinking tube around which the actual backpack has been built up. Some hydration packs consist only of the bladder and some shoulder straps while others might have a casing and side pockets which make them real backpacks. Larger backpacks generally do not have a fixed bladder but have a special compartment to facilitate the insertion of a bladder and have a hole for the drinking tube. Camelbak is one of the best known producers of hydration packs. Generic Types of Backpack Day Packs Volume: 15 to 35 liters The name Day Pack already gives away its intended use: Day Hikes. -

View Packing Lists

BOLD & GOLD EXPEDITIONS GENERAL PACKING INFORMATION All participants are responsible for bringing the items on the following list with them to check-in. Please check with your teen that every item is actually going into their pack before leaving home. Please take note of additional items necessary for your specific programs (see pages 12-18 in the handbook). The quality of clothing and equipment can have an enormous impact on the health and happiness of participants. When selecting equipment, size and weight can be important. BOLD & GOLD can provide many of these items, including clothing from an extensive outdoor clothing lending library; please call with any questions or to rent any gear. PACKING Since your teen will be carrying their own equipment as well as a portion of the group’s food and gear, choose personal gear that is lightweight, warm and easily packed. All items should be packed in a backpack that has a minimum capacity of 60-70 Liters, and should be capable of carrying 25-30 lbs. It should be an internal frame design and have adjustable hip and waist belts. If you will be renting a backpack from BOLD & GOLD, please bring gear in a duffel bag to check-in. CLOTHING Your teen will be living outside, so having the right clothing is important for their comfort and safety. There could be rain, snow, hot sun, or strong winds on your course. Our clothing list reflects the importance of the “layering” principle. Dressing in several light layers rather than one heavy layer allows them more flexibility as the weather and workloads change. -

Armor-Bags-Catalog.Pdf

I AM I AM I AM MESH MESH MESH MADE IN THE USA #67 Weight Carry Bag #173 ® #67 The Gear Wrap - Backpack • Made with MICROBAN infused heavy mesh ZIP • Build your dive bag around your gear, don't stuff your gear into a bag from the top • Made with MICROBAN infused MADE IN THE USA • Colors: Black only • Designed for carrying hard or soft weights heavy mesh • Size: 29x17" • Constructed with nylon webbing straps • Wide zipper opening • Continuous loop webbing carry system for • Non-corrosive zipper maximum strength • Continuous loop webbing carry system #84 • Reinforced bottom for maximum strength #28DX Heavy Nylon Mesh Backpack • Colors: black, blue, yellow, red • Size: 12” x 10” x 5” • Reinforced bottom Rubber Coated • Colors: black blue yellow red Mesh Backpack • Size: 11.5" x 9" x 6" Armor Mesh Backpacks Colors: black only • Pro quality backpack straps with chest strap • Full length side zipper for easy access • Extra heavy duty mesh and fabric #161 Round • Semi-dry pocket inside back Regulator Bag • Colors: Black, Blue and Yellow • 5mm closed cell foam • Size: 30" x 16" #19 DBL-MKV Double padding Regulator Bag • 600D polyester • Carries 2 sets of regulators and dive computers • Powder coated, or laptop New anti-corrosion zipper • Hide away backpack straps • size 14" x 5" #169 • Over 1" of padding on each side Dry Backpack • Interior hold-down straps • Durable tarpaulin waterproof material • Sleeve for sliding over luggage handles • Roll top closure and nylon web securing strap MADE IN THE USA • Side cinch straps for added security • Fully adjustable aero-mesh padded shoulder straps #13-41 and back padding for added comfort Mesh Boat Trash Bag/ • Lumbar support strap • 7”x 9” zippered inner nylon pouch #9DF Dive Flag • 2 mesh water bottle sleeves • 15”x 26”x 6”- 2340 Cubic In. -

Build the Perfect Bug out Bag: Your 72-Hour Disaster Survival Kit

BUILD THE PERFECT BUG OUT BAG YOUR 72-HOUR DISASTER SURVIVAL KIT Creek Stewart BETTERWAY HOME CINCINNATI, OHIO WWW.BETTERWAYBOOKS.COM CONTENTS Introduction CHAPTER 1: Meet BOB—The Bug Out Bag Getting to Know BOB Four Key Attributes of a Bug Out Bag CHAPTER 2: The Bug Out Bag: Choosing Your Pack Backpack Styles Size Does Matter Key Features of a BOB For Families, Does Everyone Need a BOB? Stocking Your Pack Chapter Organization Disaster-Prone Considerations CHAPTER 3: Water & Hydration Containers Water Purification On the Go Water Filter Verses Water Purifier CHAPTER 4: Food & Food Preparation Bug Out Survival Food Specific Suggested BOB Foods Baby/Infant Food Items Special Dietary Needs Biannual Review Food Preparation BOB Cook Kit Contents Convenience Items Heat Sources Pressurized Gas Stoves CHAPTER 5: Clothing Weather Appropriate Clothing Specifications Bug Out Clothing Guidelines Protecting Your Feet Cold Weather Essentials Cold Weather Accessories Rain Poncho Durable Work Gloves Shemagh CHAPTER 6: Shelter & Bedding BOB Shelter Option 1: Tarp Shelter Tarp Shelter Insights The Many Uses of a Tarp BOB Shelter Option 2: Tent Shelter Poncho Shelter Bug Out Bedding Bug Out Sleeping Bag Ground Sleeping Pad CHAPTER 7: Fire Your Fire Kit Ignition Sources Fire-Starting Tinder Building a Fire CHAPTER 8: First Aid Prepackaged First Aid Kits First Aid Kit Containers Kit Contents Miscellaneous Medical Items Personalizing Your First Aid Kit CHAPTER 9: Hygiene Public Hygiene Personal Hygiene BOB Personal Hygiene Pack Items CHAPTER 10: Tools Bug -

The-Ultimate-Survival-Kit-Checklist.Pdf

The Ultimate Bug Out Bag Checklist Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 3 9 GOLDEN RULES TO BUILDING A BUG OUT BAG ......................................... 5 1) COMFORTABLE WEIGHT ........................................................................... 5 2) KEEP IT “GRAY” ...................................................................................... 5 3) KEEP IT MODULAR................................................................................... 5 4) BUG OUT BUDDIES.................................................................................. 6 5) BUG OUT LOCATION ................................................................................ 6 6) YOUR ENVIRONMENT ............................................................................... 7 7) YOUR HEALTH ......................................................................................... 7 8) MORE SKILLS = LESS WEIGHT ................................................................. 7 9) QUALITY, NOT QUANTITY ......................................................................... 7 THE BUG OUT BAG LIST ............................................................................... 9 SURVIVAL BACKPACKS .............................................................................. 10 HIKING BACKPACK: .................................................................................. 13 SHELTER AND BASE CAMP MODULE CHECKLIST ........................................ 16 FIRST AID MODULE -

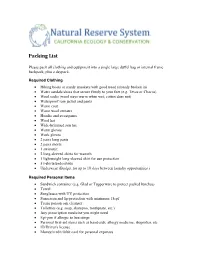

Packing List

Packing List Please pack all clothing and equipment into a single large duffel bag or internal frame backpack, plus a daypack. Required Clothing • Hiking boots or sturdy sneakers with good tread (already broken in) • Water sandals/shoes that secure firmly to your feet (e.g. Tevas or Chacos) • Wool socks (wool stays warm when wet; cotton does not) • Waterproof rain jacket and pants • Warm coat • Warm wool sweater • Hoodie and sweatpants • Wool hat • Wide-brimmed sun hat • Warm gloves • Work gloves • 2 pairs long pants • 2 pairs shorts • 1 swimsuit • 2 long-sleeved shirts for warmth • 1 lightweight long-sleeved shirt for sun protection • 5 t-shirts/undershirts • Underwear (Budget for up to 10 days between laundry opportunities.) Required Personal Items • Sandwich container (e.g. Glad or Tupperware to protect packed lunches) • Towel • Sunglasses with UV protection • Sunscreen and lip protection with minimum 15spf • Tecnu poison oak cleanser • Toiletries (e.g. soap, shampoo, toothpaste, etc.) • Any prescription medicine you might need • Epi-pen if allergic to bee stings • Personal first-aid items such as band-aids, allergy medicine, ibuprofen, etc. • ID/Driver's license • Money/credit/debit card for personal expenses Required Equipment • Laptop computer with wireless connectivity, sufficient battery life, MS Office, and JMP Statistical Software (JMP is available through your home campus, you must have it loaded and tested for functionality before arrival to the course) • Small tent (1-2 person) with durable rainfly and footprint tarp • Warm sleeping bag (Temperatures may dip below freezing: if your sleeping bag is not rated at 20° F or colder, you will need to bring a sleeping bag liner as well.) • Packable inflatable sleeping pad (e.g. -

Back at Ya 2.0 Class Description and Supply List

Back At Ya 2.0 Class Description The perfect size for a small purse or for a child’s school backpack, this bag is packed with pockets: • Full zippered pocket on the back • Zippered pocket of fabric or mesh inside the bag • Two interior slip pockets for cell phone, keys, glasses, and more • An outer front slip pocket hides even more pockets for IDs, credit cards, library and loyalty cards, room keys, and more You will master several new skills in this class: • Attach invisible magnets to close the flap on the outer pocket • Make staggered slip pockets to hold credit cards • Install rectangle rings and sliders to make attached, adjustable straps • Understand the importance of completing the pattern steps in the proper order • Adjust the shape of the front, back, and sides of the bag for a less boxy appearance. Class Supply List Back At Ya 2.0 pattern Fabric and supplies as listed on pattern cover (see next page) Thread to match fabrics ALSO BRING TO CLASS: Sewing machine in good working order with walking foot, ¼" foot, and zipper foot. Don’t forget the extension table for your machine. Rotary cutter and rulers Quick Turn Fabric Tube Turner (or similar product) Basic sewing kit, including #90/14 Topstitch needles, Wonder Clips, a stiletto/pressing tool, pins (the large yellow-topped quilting pins work best), scissors, thread, chalk marker or similar tool for marking lines, washable school glue stick, etc. BEFORE CLASS: To make best use of class time, please complete all the steps in section I. CUT AND QUILT (I-A through I-C) on page 2 of the pattern BEFORE coming to class.