Western Massachusetts Opening Doors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013-2014 Legislative Scorecard

Legislative Scorecard Votes and Leadership 2013-14 LEGISLATIVE SESSION - 1 - This is the inaugural edition of the Environmental League of Massachusetts legislative scorecard. We produced this scorecard to inform citizens about how their legislators voted on important environmental issues. We are pleased and grateful for the support of so many environmental leaders in the legislature. The scorecard relies first on roll call votes on legislation that deals with environmental and energy issues. Because there are so few roll call votes each session—and often these votes are unanimous—we have scored additional actions by legislators to further distinguish environmental champions. Bonus points were awarded to legislators who introduced bills that were ELM priorities or who introduced important amendments, particularly budget amendments to increase funding for state environmental agencies. In addition, we subtracted points for legislators who introduced legislation or amendments that we opposed. We want to recognize leadership and courage, in addition to votes, and have made every attempt to be fair and transparent in our scoring. Much happens during the legislative process that is impractical to score such as committee redrafts, committee votes to move or hold a bill, and measures that would improve flawed legislation. We have not attempted to include these actions, but we recognize that they greatly influence the process and outcomes. None of the bills or amendments scored here should be a surprise to legislators in terms of ELM’s support or opposition. Going forward, ELM will include votes and other actions that support additional revenues for transportation and promote transit, walking and biking. George Bachrach, President Erica Mattison, Legislative Director Highlights of the Session projects. -

Legislative Profiles Spring 2019 |

Legislative Profiles Spring 2019 | Announcement Inside This Issue This portfolio contains the profiles of all legislators that belong to PG. 2: Forward key committees within the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. PG. 4: House Bill – H.2366 Each key committee will play a role in the review and approval of the retirement bills that have been filed. PG. 8: Senate Bill – SD.1962 PG. 11: Joint Committee on Public Service – Profiles PG. 29: House Ways & Means – Profiles This portfolio is for the members of MCSA to use to determine PG. 63: House Committee on Third Reading – Profiles which members reside within their regions so contact can be made with each legislator for support of both retirement bills. PG. 67: Senate Ways & Means – Profiles PG. 86: Senate Committee on Third Reading – Profiles PG. 92: Talking Point Tips PG. 93: Legislative Members by MCSA Regions FORWARD Many of us do not have experience with advocating for legislation or meeting with our legislative representatives. This booklet was created with each you in mind to assist in determining which members reside within your region or represent your town and city. We request you contact your respective legislators for support of both retirement bills. If you are familiar with the legislative process and your representatives this may seem rudimentary. The Massachusetts Legislature is comprised of 200 members elected by the people of the Commonwealth. The Senate is comprised of 40 members, with each representing a district of approximately 159,000 people. The House of Representatives is comprised of 160 members, with each legislator representing districts consisting of approximately 40,000 people. -

Preparing for a School Year Like No Other!

BOSTON TEACHERS UNION, LOCAL 66, AFT Non-Profit Org. 180 Mount Vernon Street U.S. Postage Boston, Massachusetts 02125 PAID Union Information Boston, MA you can use. Permit No. 52088 Refer to this newspaper throughout the year. EVERYONE ¡TODOS IS SON WELCOME BIENVENIDOS BBOSTON TEACHERSU HERE! AQUÍ! TUNION BT U BT U The Award-Winning Newspaper of the Boston Teachers Union, AFT Local 66, AFL-CIO • Volume 53, Number 1 • September, 2020 President’s Report Jessica J. Tang Preparing For A School Year Like No Other! ypically, each fall, we begin the new caravan and rally ending at City Hall It is only through our collective Tschool year with much anticipation, with hundreds of members, filling the action, the demonstration of our unity, hope and expectation. We eagerly pre- parking lot of Madison Park and circling strength and purpose that we have been pare our classrooms and look forward to the BPS headquarters before heading to able to make progress since the “hop- meeting new students and a fresh start. circle City Hall. scotch” plan was revealed. Since then, 2020, however, has brought unprec- We joined hundreds of educators we were able to win a delay in the start edented challenges and the usual excite- from across the state the next week for of the school year so that educators had Jessica J. Tang ment that a new school year brings has another car caravan—this time circling time to get professional development and BTU President been filled with strife and anxiety of the the State House as hundreds more educa- training in safety and health protocols. -

MA CCAN 2020 Program FINAL

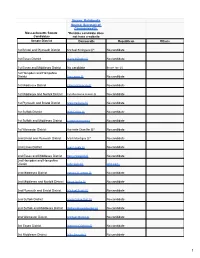

Source: Ballotpedia Source: Secretary of Commonwealth Massachusetts Senate *Denotes candidate does Candidates not have a website Senate District Democratic Republican Others 1st Bristol and Plymouth District Michael Rodrigues (i)* No candidate 1st Essex District Diana DiZoglio (i) No candidate 1st Essex and Middlesex District No candidate Bruce Tarr (i) 1st Hampden and Hampshire District Eric Lesser (i) No candidate 1st Middlesex District Edward Kennedy (i) No candidate 1st Middlesex and Norfolk District Cynthia Stone Creem (i) No candidate 1st Plymouth and Bristol District Marc Pacheco (i) No candidate 1st Suffolk District Nick Collins (i) No candidate 1st Suffolk and Middlesex District Joseph Boncore (i) No candidate 1st Worcester District Harriette Chandler (i)* No candidate 2nd Bristol and Plymouth District Mark Montigny (i)* No candidate 2nd Essex District Joan Lovely (i) No candidate 2nd Essex and Middlesex District Barry Finegold (i) No candidate 2nd Hampden and Hampshire District John Velis (i) John Cain 2nd Middlesex District Patricia D. Jehlen (i) No candidate 2nd Middlesex and Norfolk District Karen Spilka (i) No candidate 2nd Plymouth and Bristol District Michael Brady (i) No candidate 2nd Suffolk District Sonia Chang-Diaz (i) No candidate 2nd Suffolk and Middlesex District William Brownsberger (i) No candidate 2nd Worcester District Michael Moore (i) No candidate 3rd Essex District Brendan Crighton (i) No candidate 3rd Middlesex District Mike Barrett (i) No candidate 1 Source: Ballotpedia Source: Secretary of Commonwealth -

Carbon Pricing Lobby Day June 13, 2017 HOUSE

Carbon Pricing Lobby Day June 13, 2017 HOUSE MEETINGS Angelo D’Emilia Andy Gordon: 440-799-3480 Time: 1pm Room: 548 Cory Atkins Staff/#: Andy Gordon 440-799-3480 Time: 1pm Room: 195 Mike Day Leader/#: Janet Lawson, Launa Zimmaro Time: 12:30pm Room: 473f Ruth Balser Leader/#: Mary Jo Maffei 413-265-6390 (staff) Time: 1pm Room: 136 Margaret Decker Leader/#: Marcia Cooper, 617-416-1969 Time: 12pm Room: 166 Christine Barber Leader/#: Grady McGonagle, Time: 10:30am Room: 473f Carolyn Dykema Leader/#: Grace Hall Time: 3:00pm Room: 127 Don Berthiaume Leader/#:Christine Perrin Time: 2pm Room: 540 Lori Ehrlich Leader/#: Rebecca Morris 617-513-1080 (staff) Time: 2pm Room: 167 Paul Brodeur Leader/#: Clyde Elledge Time: 2pm, aide Patrick Prendergast Room: 472 Sean Garballey Leader/#: Time: 2:30pm Room: 540 Gailanne Cariddi Leader/#: Time: 11am Room: 473f Denise Garlick Leader/#: Mary Jo Maffei Time: 2pm Room: 33 Evandro Carvalho Leader/#: Janet Bowser, Cindy Luppi Time: 1:30pm, with aide Luca 617-640-2779 (staff) Room: 136 Leader/#: Joel Wool, 617-694-1141 (staff) Carmine Gentile Time: 2:30pm Mike Connolly Room: 167 Time: 12:30 Leader/#: Eric Lind Room: 33 (basement) Leader/#: Jon Hecht Time: 2:30pm Ed Coppinger Room: 22 Time: 2:30 Leader/#: Room: 26 Leader/#: Vince Maraventano 1 Brad Hill Jay Livingstone Time: 1pm Time: 1:30pm Room: 128 Room: 472 Leader/#: Erica Mattison (staff), Joy Gurrie Leader/#: Kate Hogan Liz Malia Time: 1:30pm Time: 2pm Room: 130 Room: 238 Leader/#: Marc Breslow 617-281-6218 (staff) Leader/#: Amanda Sebert, 630-217-2934 (staff) -

METCO Legislators 2020

Phone (617) Address for newly District Senator/Representative First Name Last Name 722- Room # Email elected legislators Boston Representative Aaron Michlewitz 2220 Room 254 [email protected] Boston Representative Adrian Madaro 2263 Room 473-B [email protected] Natick, Weston, Wellesley Representative Alice Hanlon Peisch 2070 Room 473-G [email protected] East Longmeadow, Springfield, Wilbraham Representative Angelo Puppolo 2006 Room 122 [email protected] Boston Representative Rob Consalvo [email protected] NEW MEMBER Needham, Wellesley, Natick, Wayland Senator Becca Rausch 1555 Room 419 [email protected] Reading, North Reading, Lynnfield, Middleton Representative Bradley H. Jones Jr. 2100 Room 124 [email protected] Lynn, Marblehead, Nahant, Saugus, Swampscott, and Melrose Senator Adam Gomez [email protected] NEW MEMBER Longmeadow, Hampden, Monson Representative Brian Ashe 2430 Room 236 [email protected] Springfield Representative Bud Williams 2140 Room 22 [email protected] Springfield Representative Carlos Gonzales 2080 Room 26 [email protected] Sudbury and Wayland, Representative Carmine Gentile 2810 Room 167 [email protected] Boston Representative Chynah Tyler 2130 Room 130 [email protected] Woburn, Arlington, Lexington, Billerica, Burlington, Lexington Senator Cindy Friedman 1432 Room 413-D [email protected] Boston Senator Nick Collins 1150 Room 410 [email protected] Newton, Brookline, Wellesley Senator Cynthia Stone Creem 1639 Room 312-A [email protected] Boston, Milton Representative Dan Cullinane 2020 Room 527-A [email protected] Boston, Milton Representative Fluker Oakley Brandy [email protected] Boston, Chelsea Representative Daniel Ryan 2060 Room 33 [email protected] Boston Representative Daniel J. -

Commonwealth Heroine Class of 2021

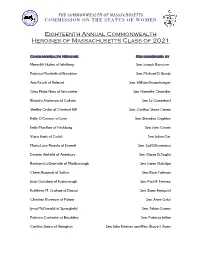

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN Eighteenth Annual Commonwealth Heroines of Massachusetts Class of 2021 Commonwealth Heroine Recommended by Meredith Hurley of Winthrop Sen. Joseph Boncore Patricia Monteith of Brockton Sen. Michael D. Brady Amy Kirsch of Belmont Sen. William Brownsberger Gina Plata-Nino of Worcester Sen. Harriette Chandler Rhonda Anderson of Colrain Sen. Jo Comerford Shelley Crohn of Chestnut Hill Sen. Cynthia Stone Creem Kelly O’Connor of Lynn Sen. Brendan Crighton Emily MacRae of Fitchburg Sen. John Cronin Vaira Harik of Cotuit Sen. Julian Cyr María Lucy Pineda of Everett Sen. Sal DiDomenico Doreen Arnfield of Amesbury Sen. Diana DiZoglio Barbara LaGrenade of Marlborough Sen. James Eldridge Cheryl Rawinski of Sutton Sen. Ryan Fattman Joan Goodwin of Foxborough Sen. Paul R. Feeney Kathleen M. Graham of Dracut Sen. Barry Finegold Christina Florence of Palmer Sen. Anne Gobi Jynai McDonald of Springfield Sen. Adam Gomez Patricia Contente of Brookline Sen. Patricia Jehlen Cynthia Sierra of Abington Sen. John Keenan and Rep. Bruce J. Ayers THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN Eighteenth Annual Commonwealth Heroines of Massachusetts Class of 2021 Commonwealth Heroine Recommended by Heather Prince Doss of Lowell Sen. Ed Kennedy Sandra E. Sheehan of Hampden Sen. Eric Lesser Laura Rosi of Malden Sen. Jason Lewis Nancy Frates of Beverly Sen. Joan B. Lovely Corinn Williams of New Bedford Sen. Mark Montigny Darlene Coyle of Leicester Sen. Michael Moore Kathleen Jespersen of North Falmouth Sen. Susan Moran and Rep. David Vieira Jennifer McCormack Vitelli of Marshfield Hills Sen. Patrick O’Connor Ndoumbe Ndoyelaye of Franklin Sen. -

Sent a Letter

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts General Court July 31, 2020 Chief Kenneth Green MBTA 240 Southampton Street Boston, MA 02118 Dear Chief Green, It has come to our attention that the Transit Police have recently disbanded their highly regarded and respected Transit SWAT unit. As public officials and stewards of taxpayer resources, we can appreciate the need to ensure that resources are most appropriately allocated. We question the rationale of this decision and the long-term effects on the safety of the riders of the transit system and preparedness of the Transit Police to respond to an incident within their jurisdiction. While well intentioned, the disbandment of a SWAT unit trained specifically to deal with issues on our transit system seems ill advised. The fact that they have not been utilized much over the last few years does not mean that they aren’t a vital and necessary component to the public safety responsibilities and emergency operations that will be required. As we have seen in other countries, a public transit system is often a target for both foreign and domestic terrorism and having a SWAT unit with specialized training ensures that we remain vigilant and ready to face such threats to public safety. We are respectfully requesting that you share the reasoning for the decision to disband the transit SWAT team and to explain in detail what measures you have put in place to replace the loss of this specially trained force. We would also like to know the costs associated with the Transit unit and what savings you expect to realize as a result of this decision. -

Previous Legislative Actions Pertaining to the Holyoke Soldiers’ Home

HOUSE DOCKET, NO. FILED ON: 6/1/2021 HOUSE . No. 3857 The Commonwealth of Massachusetts _____________ THE FINAL REPORT OF THE JOINT OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE (ESTABLISHED UNDER HOUSE ORDER NO. 4835 OF THE 191ST GENERAL COURT) TO MAKE AN INVESTIGATION AND STUDY OF THE SOLDIERS’ HOME IN HOLYOKE COVID-19 OUTBREAK. ________________ June 3, 2021. __________________ Massachusetts General Court | May 2021 Report of the Special Joint Oversight Committee on the Soldiers’ Home in Holyoke COVID-19 Outbreak Findings & Recommendations To care for those “who shall have borne the battle” and for their families and survivors – Abraham Lincoln Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction and Purpose of Report ........................................................................................... 2 Establishment of the Special Committee .................................................................................... 4 Scope of the Committee .............................................................................................................. 5 Committee Membership .............................................................................................................. 6 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 8 Findings and Recommendations ............................................................................................... -

MASC Legislative Directory 2020

2020 Massachusetts State Legislative Directory Massachusetts Constitutional Officers Governor Charlie Baker (617) 725-4005 Room 280 Lt. Governor Karyn Polito (617) 725-4005 Room 360 Treasurer Deborah Goldberg (617) 367-6900 Room 227 Atty. General Maura Healey (617) 727-2200 1 Ashburton Place, 18th Floor [email protected] Sec. of the State William Galvin (617) 727-9180 Room 340 [email protected] State Auditor Suzanne Bump (617) 727-2075 Room 230 [email protected] Massachusetts Senate (617) 722- Email (@masenate.gov) Room # (617) 722- Email (@masenate.gov) Room # Michael Barrett 1572 Mike.Barrett 109-D Patricia Jehlen 1578 Patricia.Jehlen 424 Joseph Boncore 1634 Joseph.Boncore 112 John Keenan 1494 John.Keenan 413-F Michael Brady 1200 Michael.Brady 416-A Edward Kennedy 1630 Edward.Kennedy 70 William Brownsberger 1280 William.Brownsberger 319 Eric Lesser 1291 Eric.Lesser 410 Harriette Chandler 1544 Harriette.Chandler 333 Jason Lewis 1206 Jason.Lewis 511-B Sonia Chang-Diaz 1673 Sonia.Chang-Diaz 111 Joan Lovely 1410 Joan.Lovely 413-A Nick Collins 1150 Nick.Collins 312-D Mark Montigny 1440 Mark.Montigny 312-C Joanne Comerford 1532 Jo.Comerford 413-C Michael Moore 1485 Michael.Moore 109-B Cynthia Creem 1639 Cynthia.Creem 312-A Patrick O'Connor 1646 Patrick.OConnor 419 Brendan Crighton 1350 Brendan.Crighton 520 Marc Pacheco 1551 Marc.Pacheco 312-B Julian Cyr 1570 Julian.Cyr 309 Rebecca Rausch 1555 Becca.Rausch 218 Sal DiDomenico 1650 Sal.DiDomenico 208 Michael Rodrigues 1114 Michael.Rodrigues 212 Diana DiZoglio 1604 Diana.DiZoglio 416-B -

Senate House Massachusetts House of Representatives

Senate House Massachusetts House of Representatives Representative Dylan Fernandes, (Barnstable, Dukes & Nantucket) Phone: (617) 722-2013 Email: [email protected] Cities: Nantucket, Falmouth, Chilmark, Aquinnah, Gosnold, Oak Bluffs, Tisbury, West Tisbury Representative Timothy Whelan, (1st Barnstable) Phone: (617) 722-2488 Email: [email protected] Cities: Dennis, Brewster, Yarmouth Representative Kip Diggs, (2nd Barnstable) Phone: (617) 722-2800 Email: [email protected] Cities: Barnstable, Yarmouth Representative David Vieira, (3rd Barnstable) Phone: (617) 722-2230 Email: [email protected] Cities: Teaticket (Falmouth), Bourne, Mashpee Representative Sarah Peake, (4th Barnstable) Phone: (617) 722-2040 Email:[email protected] Cities Provincetown, Chatham, Eastham, Harwich, Orleans, Truro, Wellfleet Representative Steven Xiarhos, (5th Barnstable) Phone: (617) 722-2800 Email: [email protected] Cities Sandwich, Barnstable, Bourne, Plymouth Representative John Barrett, (1st Berkshire) Phone: (617) 722-2305 Email: [email protected] North Adams, Adams, Clarksburg, Florida, Williamstown, Chesire, Hancock, Lanesborough, New Ashford Representative Paul Mark, (2nd Berkshire) Phone: (617) 722-2304 Email: [email protected] Bernardston, Colrain, Dalton, Hinsdale, Leyden, Northfield, Peru, Pittsfield, Savoy, Windsor, Greenfield, Charlemont, Hawley, Heath, Monroe, Rowe Representative Tricia Farley-Bouvier, (3rd Berkshire) -

Velis Testifies on Bill That Supports Military Families by HOPE E

The Westfield NewsSearch for The Westfield News Westfield350.com The WestfieldNews Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns “TIME IS THE ONLY WEATHER CRITIC WITHOUT TONIGHT AMBITION.” Partly Cloudy. JOHN STEINBECK Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com $1.00 VOL. 86 NO. 151 THURSDAY,TUESDAY, JUNE JULY 27, 8, 2017 2021 VOL. 75 cents 90 NO. 158 Velis testifies on bill that supports military families By HOPE E. TREMBLAY Velis said for military families, fre- ation, we are also greatly hurting our Editor quent moves is a way of life. force retention rate and jeopardizing BOSTON – State Sen. John C. “Depending on the assignment, our military’s ability to be troop Velis July 6 gave testimony to the military members change stations ready,” he said. “Similarly, the chil- Veterans and Federal Affairs every 24-36 months on average. This dren of service members are impacted Committee in support of the SPEED uprooting not only affects the service- by these transitions as well.” Act. member, it affects their entire family He said families often miss out on The SPEED Act is Senate Bill as well,” he said. registration deadlines because they 2433, An Act relative to military Because of this, military spouses are uprooted mid-year and college spouse licensure portability, educa- who hold professional licenses in students, many of whom rely on in- STATE SEN. JOHN C. VELIS tion and enrollment of dependents. other states have to reapply for their state tuition rates, are also affected. Velis is co-chair of the committee license in the Commonwealth. “This “These are critical issues that our military families in their transi- This legislation, said Velis, with state Rep.