Watershed Condition Framework: 2011-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

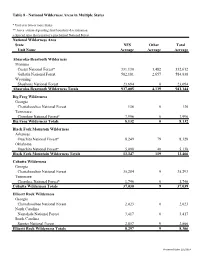

Table 8 — National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States

Table 8 - National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest National Wilderness Area State NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Montana Custer National Forest* 331,130 1,482 332,612 Gallatin National Forest 582,181 2,657 584,838 Wyoming Shoshone National Forest 23,694 0 23,694 Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Totals 937,005 4,139 941,144 Big Frog Wilderness Georgia Chattahoochee National Forest 136 0 136 Tennessee Cherokee National Forest* 7,996 0 7,996 Big Frog Wilderness Totals 8,132 0 8,132 Black Fork Mountain Wilderness Arkansas Ouachita National Forest* 8,249 79 8,328 Oklahoma Ouachita National Forest* 5,098 40 5,138 Black Fork Mountain Wilderness Totals 13,347 119 13,466 Cohutta Wilderness Georgia Chattahoochee National Forest 35,284 9 35,293 Tennessee Cherokee National Forest* 1,746 0 1,746 Cohutta Wilderness Totals 37,030 9 37,039 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Georgia Chattahoochee National Forest 2,023 0 2,023 North Carolina Nantahala National Forest 3,417 0 3,417 South Carolina Sumter National Forest 2,857 9 2,866 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Totals 8,297 9 8,306 Processed Date: 2/5/2014 Table 8 - National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest National Wilderness Area State NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage -

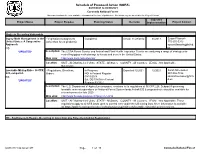

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Boise National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Boise National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Gypsy Moth Management in the - Vegetation management Completed Actual: 11/28/2012 01/2013 Susan Ellsworth United States: A Cooperative (other than forest products) 775-355-5313 Approach [email protected]. EIS us *UPDATED* Description: The USDA Forest Service and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are analyzing a range of strategies for controlling gypsy moth damage to forests and trees in the United States. Web Link: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/wv/eis/ Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Nationwide. Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders NOI in Federal Register 907-586-7886 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 03/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. -

Forest Songbird Abundance and Viability at Multiple Scales on the Monongahela National Forest, West Virginia

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 1999 Forest songbird abundance and viability at multiple scales on the Monongahela National Forest, West Virginia Thomas Eugene DeMeo West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation DeMeo, Thomas Eugene, "Forest songbird abundance and viability at multiple scales on the Monongahela National Forest, West Virginia" (1999). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 1045. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/1045 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOREST SONGBIRD ABUNDANCE AND VIABILITY AT MULTIPLE SCALES ON THE MONONGAHELA NATIONAL FOREST, WEST VIRGINIA Thomas Eugene DeMeo Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the College of Agriculture and Forestry West Virginia University In Partial -

IMBCR Report

Integrated Monitoring in Bird Conservation Regions (IMBCR): 2015 Field Season Report June 2016 Bird Conservancy of the Rockies 14500 Lark Bunting Lane Brighton, CO 80603 303-659-4348 www.birdconservancy.org Tech. Report # SC-IMBCR-06 Bird Conservancy of the Rockies Connecting people, birds and land Mission: Conserving birds and their habitats through science, education and land stewardship Vision: Native bird populations are sustained in healthy ecosystems Bird Conservancy of the Rockies conserves birds and their habitats through an integrated approach of science, education and land stewardship. Our work radiates from the Rockies to the Great Plains, Mexico and beyond. Our mission is advanced through sound science, achieved through empowering people, realized through stewardship and sustained through partnerships. Together, we are improving native bird populations, the land and the lives of people. Core Values: 1. Science provides the foundation for effective bird conservation. 2. Education is critical to the success of bird conservation. 3. Stewardship of birds and their habitats is a shared responsibility. Goals: 1. Guide conservation action where it is needed most by conducting scientifically rigorous monitoring and research on birds and their habitats within the context of their full annual cycle. 2. Inspire conservation action in people by developing relationships through community outreach and science-based, experiential education programs. 3. Contribute to bird population viability and help sustain working lands by partnering with landowners and managers to enhance wildlife habitat. 4. Promote conservation and inform land management decisions by disseminating scientific knowledge and developing tools and recommendations. Suggested Citation: White, C. M., M. F. McLaren, N. J. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Coronado National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Gypsy Moth Management in the - Vegetation management Completed Actual: 11/28/2012 01/2013 Susan Ellsworth United States: A Cooperative (other than forest products) 775-355-5313 Approach [email protected]. EIS us *UPDATED* Description: The USDA Forest Service and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are analyzing a range of strategies for controlling gypsy moth damage to forests and trees in the United States. Web Link: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/wv/eis/ Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Nationwide. Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders NOI in Federal Register 907-586-7886 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 03/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. -

2011 National Wilderness Awards Announcement

Forest Washington 1400 Independence Avenue, SW Service Office Washington, DC 20250 File Code: 2320 Date: July 1, 2011 Route To: Subject: 2011 National Wilderness Awards Announcement To: Regional Foresters, Station Directors, Area Director, IITF Director, Deputy Chiefs I am pleased to announce the recipients of the 2011 National Wilderness Awards. These awards honor individuals and groups for excellence in wilderness stewardship. This national award encompasses education, traditional skills and minimum tools leadership, and overall wilderness stewardship. The 2011 National Wilderness Award recipients are: Aldo Leopold Award for Overall Wilderness Stewardship Program Stanislaus Wilderness Volunteers—The Stanislaus Wilderness Volunteer organization is being recognized for sponsoring two wilderness ranger interns to assist the Stanislaus wilderness crew with invasive species management in wilderness areas. The Stanislaus Volunteer organization started their own wilderness intern program, and increased the group’s capacity to complete wilderness stewardship projects by 20 percent. The Stanislaus Volunteer organization is also a leader in wilderness and Leave No Trace education. The organization secured a grant from the Tides Foundation California Wilderness Grassroots Fund to co-sponsor a Leave No Trace Master Educator course in partnership with the Stanislaus National Forest and Yosemite National Park. Bob Marshall Award for Individual Champion of Wilderness Stewardship Deb Gale, Bitterroot National Forest—Deb is active in regional and national wilderness issues. She served as Co-chair for the Chief’s Wilderness Advisory Group from 2005-2008, and has taken a leadership role on the Anaconda-Pintler, Frank Church, and Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness Management Teams. These three wilderness teams have complex coordination needs because they are managed by multiple National Forests, multiple Forest Service Regions, and multiple States. -

Table of Contents

TABLEGUIDELINES OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 12: CONTACT INFORMATION AND MAPS 12.1 ADOT CONTACT INFORMATION……………………………………………….......122 12.2 BLM CONTACT INFORMATION…………………………………………………......123 12.3 USFS CONTACT INFORMATION………………………………………………….....124 12.4 FHWA CONTACT INFORMATION…………………………………………………....130 12.5 GIS INFORMATION..............................................................................................131 12.6 MAPS...................................................................................................................132 121 12.1 ADOT CONTACT INFORMATION ADOT web link azdot.gov/ ADOT maps azdot.gov/maps General Information 602-712-7355 OFFICE ADOT DIRECTOR 602.712.7227 Deputy Director of Transportation 602.712.7391 Deputy Director of Policy 602.712.7550 Deputy Director of Business Operations 602.712.7228 Multimodal Planning Division (MPD) Director 602.712.7431 MPD Planning and Programming Director 602.712.8140 MPD Planning and Environmental Linkages Manager 602.712.4574 Infrastructure Delivery and Operations Division (IDO) 602.712.7391 State Engineer, Sr. Deputy State Engineer and Deputy State Engineer Offices 602.712.7391 DISTRICT ENGINEERS Northcentral azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northcentral 928.774.1491 Northeast azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northeast 928.524.5400 Central Construction District azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/central 602.712.8965 Central Maintenance District azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/central 602.712.6664 Northwest azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northwest 928.777.5861 -

USDA Forest Service Guidelines for Consultants for Identifying, Recording, & Evaluating Archaeological Resources in UTAH April 20, 2020

USDA Forest Service Guidelines for Consultants for Identifying, Recording, & Evaluating Archaeological Resources in UTAH April 20, 2020 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION & CONTACTS ....................................................................................................................... 2 GENERAL REQUIREMENTS ............................................................................................................................ 4 Policy ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Professional Qualifications ....................................................................................................................... 4 Bids ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Permits for Archaeological Investigations ................................................................................................ 5 Project Numbers ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Site Numbers ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Discoveries ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Confidentiality .......................................................................................................................................... -

Uinta NF Ranger Stations

United States Department of Agriculture The Enchantment of Forest Service Intermountain Region Ranger Life in the Hills UINTA NATIONAL FOREST JULY 2016 Administrative Facilities of the Uinta National Forest, 1905-1965 Historic Context & Evaluations Forest Service Report No. UWC-16-1328 Cover: Lake Creek Ranger Station, 1949 Pleasant Grove Ranger Station, 1965 “I had a carpenter hired and boarded up the house around the foundation. It was from 6 in. to 2 feet off the ground and skunks and animals frequently got under the house, which detracted some of the enchantment of Ranger Life in the Hills.” Aaron Parley Christiansen, April 26, 1919 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2021 to 09/30/2021 Ashley National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2021 to 09/30/2021 Ashley National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, On Hold N/A N/A Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders 907-586-7886 EIS [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. More Information is available at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/science-technology/geology/minerals/locatable-minerals/current-revisions. Projects Occurring in more than one Region (excluding Nationwide) 07/01/2021 07:16 pm MT Page 1 of 10 Ashley National Forest Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring in more than one Region (excluding Nationwide) Amendments to Land - Land management planning In Progress: Expected:12/2020 01/2021 John Shivik Management Plans Regarding - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Objection Period Legal Notice 801-625-5667 Sage-grouse Conservation 08/02/2019 [email protected] EIS Description: The Forest Service is considering amending its land management plans to address new and evolving issues arising since implementing sage-grouse plans in 2015. -

USDA Forest Service Youth Conservation Corps Projects 2021

1 USDA Forest Service Youth Conservation Corps Projects 2021 Alabama Tuskegee, National Forests in Alabama, dates 6/6/2021--8/13/2021, Project Contact: Darrius Truss, [email protected] 404-550-5114 Double Springs, National Forests in Alabama, 6/6/2021--8/13/2021, Project Contact: Shane Hoskins, [email protected] 334-314- 4522 Alaska Juneau, Tongass National Forest / Admiralty Island National Monument, 6/14/2021--8/13/2021 Project Contact: Don MacDougall, [email protected] 907-789-6280 Arizona Douglas, Coronado National Forest, 6/13/2021--7/25/2021, Project Contacts: Doug Ruppel and Brian Stultz, [email protected] and [email protected] 520-388-8438 Prescott, Prescott National Forest, 6/13/2021--7/25/2021, Project Contact: Nina Hubbard, [email protected] 928- 232-0726 Phoenix, Tonto National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/25/2021, Project Contact: Brooke Wheelock, [email protected] 602-225-5257 Arkansas Glenwood, Ouachita National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/30/2021, Project Contact: Bill Jackson, [email protected] 501-701-3570 Mena, Ouachita National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/30/2021, Project Contact: Bill Jackson, [email protected] 501- 701-3570 California Mount Shasta, Shasta Trinity National Forest, 6/28/2021--8/6/2021, Project Contact: Marcus Nova, [email protected] 530-926-9606 Etna, Klamath National Forest, 6/7/2021--7/31/2021, Project Contact: Jeffrey Novak, [email protected] 530-841- 4467 USDA Forest Service Youth Conservation Corps Projects 2021 2 Colorado Grand Junction, Grand Mesa Uncomphagre and Gunnison National Forests, 6/7/2021--8/14/2021 Project Contact: Lacie Jurado, [email protected] 970-817-4053, 2 projects. -

Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County

Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage Alabama 1st Escambia Conecuh National Forest 29,179 1st Totals 29,179 2nd Coffee Pea River Land Utilization Project 40 Covington Conecuh National Forest 54,881 2nd Totals 54,922 3rd Calhoun Rose Purchase Unit 161 Talladega National Forest 21,412 Cherokee Talladega National Forest 2,229 Clay Talladega National Forest 66,763 Cleburne Talladega National Forest 98,750 Macon Tuskegee National Forest 11,348 Talladega Talladega National Forest 46,272 3rd Totals 246,935 4th Franklin William B. Bankhead National Forest 1,277 Lawrence William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,681 Winston William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,030 4th Totals 181,987 6th Bibb Talladega National Forest 60,867 Chilton Talladega National Forest 23,027 6th Totals 83,894 2019 Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/19/2019 Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage 7th Dallas Talladega National Forest 2,167 Hale Talladega National Forest 28,051 Perry Talladega National Forest 32,796 Tuscaloosa Talladega National Forest 10,998 7th Totals 74,012 Alabama Totals 670,928 Alaska At Large Anchorage Municipality Chugach National Forest 248,417 Haines Borough Tongass National Forest 767,952 Hoonah-Angoon Census Area Tongass National Forest 1,974,292 Juneau City and Borough Tongass National Forest 1,672,846 Kenai Peninsula Borough Chugach National Forest 1,261,067 Ketchikan Gateway Borough Tongass