One Laptop Per Child Discourse in an Information Society Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigating Choices of Appropriate Devices for One-To-One Computing Initiatives in Schools Worldwide

International Journal of Information and Education Technology, Vol. 6, No. 10, October 2016 Investigating Choices of Appropriate Devices for One-to-One Computing Initiatives in Schools Worldwide M. Sirajul Islam and Annika Andersson schools should be governed by “creating an environment in Abstract—The use of technology in schools is rapidly which the child will become highly involved in experience of increasing – today most notably through the one-to-one (1:1) a kind to provide rich soil for the growth in intuitions and programs that are being implemented all around the world. concepts for dealing with thinking, learning, playing, and so Considering how new technologies are emerging fast and obsoleting others in schools, there is a need to continuously on” [5]. In this direction, one of the first practical initiatives monitor and understand the features of various devices in terms on implementing constructionist learning for children with of embedded technology and interaction with users. This paper computers was the development of programming language therefore presents the nature of computing devices used in 1:1 called „Logo‟ in 1967. Following such initiatives, Alan C. computing programs in schools around the world, including Kay, who was closely associated with Papert for promoting investigating the benefits and drawbacks, by means of a and implementing computer based educational constructivism, systematic literature review and a survey conducted in some schools in Sweden. The paper also presents findings based on developed a laptop computer for children in 1970 based on how the various uses of technology affect cooperation practices the sketches of the KiddiComp called „Daynabook‟ as well as personal exploration. -

One Laptop Per Child: Vision Vs. Reality

contributed articles DOI:10.1145/1516046.1516063 Although some developing coun- The vision is being overwhelmed by the reality tries are indeed deploying OLPC lap- tops, others have cancelled planned of business, politics, logistics, and competing deployments or are waiting on the interests worldwide. results of pilot projects before decid- ing whether to acquire them in num- BY KENNETH L. KRAEMER, JASON DEDRICK, AND PRAKUL SHARMA bers. Meanwhile, the OLPC organiza- tion (www.olpc.com/) struggles with SON OL key staff defections, budget cuts, and S L IE ideological disillusionment, as it ap- N , 15. pears to some that the educational C LP One Laptop mission has given way to just getting O laptops out the door. In addition, low- cost commercial netbooks from Acer, 14. ONROY, M Asus, Hewlett-Packard, and other PC Z OME G vendors have been launched with great A L Per Child: AR early success. C So rather than distributing millions , 13. C LP of laptops to poor children itself, OLPC O has motivated the PC industry to devel- RCE, 12. Vision vs. A op lower-cost, education-oriented PCs, FO FO L providing developing countries with O D O low-cost computing options directly in R competition with OLPC’s own innova- RAKE, 11. D Reality tion. In that sense, OLPC’s apparent L failure may be a step toward broader success in providing a new tool for , 10. DANIE C children in developing countries. How- LP O ever, it is also clear that the PC industry cannot profitably reach millions of the DRAKE, 7–9 poorest children, so the OLPC objec- L tives might never be achieved through the commercial market alone. -

Challenges and Impacts of One Laptop Per Child

The PRIDE Project Project Pacific Education Series, 2009 http://www.usp.ac.fj/index.php?id=publications CHALLENGES AND IMPACTS OF ONE LAPTOP PER CHILD AUTHORS • David Leeming, OLPC Coordinator, SPC http://wikieducator.org/User:Leeming • Ian Thomson, RICS and OLPC Project Manager, SPC [email protected] • Tony Forster , Games Programming Cluster of Schools, [email protected] INTRODUCTION This paper describes and advocates the One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) programme as a potentially transformational approach to much-needed education reform in the region. The main challenges for an OLPC programme are explained, based on experience from OLPC trials projects in several regional countries implemented by the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) in association with the OLPC Foundation. The paper also discusses the potential pedagogic impacts, and provides some promising early feedback from the trials projects. SUMMARY AND GOALS The regional priorities for education in the Pacific region are embodied jointly in strategies such as the Pacific Island Forum’s Forum Basic Education Plan, and nationally under the member states’ own reform programmes that are supported by various donors. These priorities include improving and transforming teacher education, curricula, and vocational education, with many voices (c.f. the University of the South Pacific’s PRIDE Project) calling for more Pacific cultural relevance and culturally appropriate pedagogy and content introduced into all of these areas, as well as a shift towards more progressive methods such as “active learning” and “learning by doing”. There are a lot of challenges within these areas. The OLPC or One Laptop Per Child is a charitable project which aims to place sub $100 laptops into the hands of third world children. -

One Laptop Per Child Birmingham: Case Study of a Radical Experiment IJLM

FORMULATIONS & FINDINGS One Laptop per Child Birmingham: Case Study of a Radical Experiment IJLM Mark Warschauer Abstract University of California, Irvine [email protected] The One Laptop per Child (OLPC) program has sought to transform education by developing Shelia R. Cotten University of Alabama, Birmingham and distributing to low-income children around [email protected] the world an inexpensive computer with an in- novative interface and applications. This article investigates the implementation of OLPC in Morgan G. Ames Stanford University Birmingham, Alabama, where some 15,000 of [email protected] the group’s XO laptops were distributed to all first- through fifth-grade public school students and their teachers. Surveys were collected from a representative sample of children before and af- Keywords ter they received their laptops, supplemented by One Laptop per Child observations and interviews in a Birmingham educational reform school. The use of the XOs by teachers and program evaluation schools, the ways social and technical infra- structure affected program implementation, and the types of XO use by students are examined. The disappointing results of the Birmingham program, which has been discontinued, are an- alyzed in relationship to OLPC’s technocentric approach, the organization’s principle of child ownership, and the design elements of the XO hardware and software. Visit IJLM.net doi:10.1162/IJLM_a_00069 c 2012 by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Published under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported license Volume 3, Number 2 Warschauer, Cotten, and Ames / One Laptop per Child Birmingham 61 FORMULATIONS & FINDINGS Introduction Negroponte joined MIT’s faculty in 1966 after earning a master’s degree in architecture from the The One Laptop per Child (OLPC) program is one of same institution. -

One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) Is a Nonprofit Organization Founded in 2005 by Nicholas Negroponte, Also the Founder of MIT's Prestigious Media Lab

One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) is a nonprofit organization founded in 2005 by Nicholas Negroponte, also the founder of MIT's prestigious Media Lab. OLPC's goal is to “create educational opportunities for the world's poorest children by providing each child with a rugged, low-cost, low-power, connected laptop with content and software designed for collaborative, joyful, self- empowered learning” (Mission Statement, OLPC). However, the history of the program was fraught with challenges, setbacks, and limitations: after 2006, when the XO laptop was manufactured and deployed in least developed countries, a variety of criticism was leveled at the project, directed both at the hardware itself and the strategies of distributing laptops to children. This literature review is an analysis of the benefits and limitations of One Laptop Per Child project within the educational sector, particularly focused on deployments in the continent of Africa. A brief history of the OLPC project and the concept of the digital divide will be followed by an analysis of the project’s five core principles. I conclude that the project’s overarching goals severely limit the adaptability of its deployments to specific geographical and cultural contexts and reduce the educational benefit of the laptops, as shown by recent evidence from deployments in Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Tanzania. One Laptop per Child Long before conceptualizing the OLPC project, Negroponte (1995) set forth a philosophy which saw the digital revolution as being problematic, yet inevitable. According to him, technology and globalization will fundamentally change the role of the nation-state, making governments “both larger and smaller” (p. -

OLPC: One Laptop Per Child Dr. Bilel Jamoussi Presented by John

Regional Development Forum 2008 “Bridging the Standardization Gap in Developing Countries” for the Asia-Pacific Region Hanoi, Vietnam, 15-17(am) September 2008 OLPC: One laptop Per Child Dr. Bilel Jamoussi Presented by John Visser, P.Eng. Chairman, ITU-T SG 19 Nortel Networks (Canada) [email protected] International Telecommunication Union One Laptop Per Child Dr. Bilel Jamoussi CTO Office Presented by John Visser, P.Eng. CTO Office - International Standards ITU Regional Development Forum 2008: “Bridging the ICT Standardization Gap in Developing Countries” Vietnam, 15-17 September Nortel2008 Confidential Information Education • In sub-Saharan Africa, more than one-third of primary school-age children are not enrolled in school at all • Those who do enter the first grade, fewer than half will complete primary school. • Schools lack resources & qualified teachers “Education is the single most • Over 100 million powerful weapon you can use to children desperately change the world .” want to go to school! Nelson Mandela One Laptop per Child A Nortel-Sponsored Project Pain Point • Availability and cost of devices Background Solution • OLPC Foundation's mission is to • Advanced Technology Collaboration on 802.11s Mesh stimulate local grassroots Technology initiatives designed to enhance and sustain over time the • OLPC is a proof point of effectiveness of XO laptops as Hyperconnectivity learning tools for children living in • Wi-Fi / WiMAX fundamental to lesser-developed countries educating the next generation One Laptop Per Child Five Principles: -

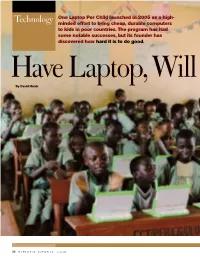

Technology One Laptop Per Child Launched in 2005 As a High

One Laptop Per Child launched in 2005 as a high- Technology minded effort to bring cheap, durable computers to kids in poor countries. The program has had some notable successes, but its founder has discovered how hard it is to do good. Have Laptop, Will Travel ■ By David Hatch 22 NATIONAL JOURNAL 4/11/09 Have Laptop, Will Travel ■ FULL CLASSROOM: One Laptop Per Child is aiming to distribute 1 million computers in each of six poor nations, including here in Nigeria. 4/11/09 NATIONAL JOURNAL 23 icholas Negroponte, the renowned MIT FOUNDER: Nicholas professor who founded the One Laptop Negroponte has flown all over the world since the Per Child Foundation, has a curious way One Laptop Foundation’s inception in 2005. He has distributed about 800,000 of demonstrating the durability of the computers, configured in 19 different languages, to pint-sized computers that the nonprofit 31 nations so far. so far. Ndistributes to the world’s most RICHARD A. BLOOM impoverished children. Halfway into an interview, he suddenly and forcefully pushes one of the machines off a table. Although such a crash might leave other laptops with mangled screens and missing keys, if not damaged beyond repair, the XO, as these devices are called, survives with nary a scratch. Showcasing the ruggedness of the trademark green-and-white laptops is easy, but persuading the world’s largest poverty-stricken nations to widely distribute them to tens of millions of schoolchil- dren has proven tougher. With vast populations of underprivileged youngsters and deep chasms be- “The most heartwarming use is where kids teach their tween rich and poor, Brazil, China, and India seem parents” to read and write. -

Why Walter Bender Left One Laptop Per Child - Bits - Technology - New York Times Blog 6/3/08 12:20 PM

Why Walter Bender Left One Laptop Per Child - Bits - Technology - New York Times Blog 6/3/08 12:20 PM HOME PAGE MY TIMES TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS My Account Welcome, bkallenberg Log Out Help Tuesday, June 3, 2008 Technology Technology All NYT WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYLE TRAVEL JOBS REAL ESTATE AUTOS PERSONAL TECH CAMCORDERS CAMERAS CELLPHONES COMPUTERS HANDHELDS HOME VIDEO MUSIC PERIPHERALS WI-FI DOWNLOADS Search This Blog All NYTimes.com Blogs » Back to front page » Latest Technology Headlines Brocade Settles Suit Over Timing of Options May 27, 2008, 7:14 pm H.P. to Put Microsoft’s Live Search in PCs Why Walter Bender Left One Laptop Per Child Well: Experts Revive Debate Over Cellphones and Cancer Microsoft Extends XP Deadline for Low-Cost PCs By STEVE LOHR More Technology News on NYTimes » Personal Technology Coverage on NYTimes » Hot Bits Is Google Violating a California Privacy Law? (39 comments) Walter Bender, left, and Nicholas Negroponte, in 2006, with an early version the computer developed by the One Laptop Per What’s It Worth: Using the Web to Appraise the Price of Child project. (Credit: Jodi Hilton for The New York Times) Everything (22 comments) The Real Fight Over Fake News (64 comments) When Microsoft joined the One Laptop Per Child project earlier this month, I wrote an Who’s Smarter: Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg? (119 comments) Why Walter Bender Left One Laptop Per Child (53 comments) article noting the change in heart by both sides. -

Using Olpc Laptop Technology As a Computer Science Case Study Teaching Tool*

USING OLPC LAPTOP TECHNOLOGY AS A COMPUTER SCIENCE CASE STUDY TEACHING TOOL* Suzanne Fox Buchele Southwestern University, 1001 East University Avenue, Georgetown, Texas 78626 (512) 863-1361 [email protected] ABSTRACT The One Laptop Per Child project has succeeded in developing a novel computer that is tailored to the particular needs of the developing world. The use of this example of a modern computer systems design challenge can be a valuable case study as a teaching tool in computer science. The OLPC laptop is a multiple-purpose computer that is rugged, low-power, mesh- networked, and inexpensive. An overview of the technology in the laptops is given, as well as curricula suggestions for using the laptops in an undergraduate computer science curriculum. INTRODUCTION The mission of the One Laptop Per Child foundation, spun out of MIT’s Media Lab, is to “create educational opportunities for the world's poorest children by providing each child with a rugged, low-cost, low-power, connected laptop with content and software designed for collaborative, joyful, self-empowered learning” [9]. The result of several years of research and development efforts is the XO Laptop, a remarkable multi-purpose mesh- networked computer with no moving parts, that uses no more than 6 watts of power (with an average of 1-3 Watts), and is currently manufactured for $188 [3, 6, 14]. This novel platform can provide a timely and interesting teaching tool for many computer science concepts, especially computer systems design. Many interesting design decisions during the development of the XO were the result of the over-arching need for low power consumption and low cost. -

The Role of One Laptop Per Child Project in Academic Performance in Primary Schools

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-3, Issue-6, Jun.-2017 http://iraj.in THE ROLE OF ONE LAPTOP PER CHILD PROJECT IN ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE IN PRIMARY SCHOOLS 1MUNYANTORE.J.D, 2MBALIRE.M. St. Lawrence University (SLAU) E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Abstract - This study titled one laptop per child project and academic performance in primary school was carried out in Gatsibo District primary school. The general objective of this study was to examine the role of OLPC project to academic performance. This study was designed under descriptive-analytical design; where both qualitative and quantitative research was used through descriptive and correlational statistics. The target population was5 heads teachers and 105 teachers from 5 primary schools in Gatsibo District. The sample size of the study was 86 respondents obtained using Yamane formula. The purposive sampling technique was used in this study. Data was collected through Questionnaire, interview and group discussion. Statistical indicators like frequencies and percentages were used in this study. To test the relationship of the variables, Pearson correlation coefficient was applied, this research used SPSS version 16 to analyze data. The study found that the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) equals to 0.935 this implies that correlation coefficient r = .942. The study recommended that Government should ensure the provision of adequate educational facilities accessible even to students from poor family. Key words- One Laptop Per Child , Academic Performance, Primary school I. INTRODUCTION knowledge-based economy. Rwanda is a small, landlocked country in Central/ East Africa. It is one All over the world, over the last three decades, the of the few OLPC deployment sites designated as a role of technology in education reform has received model site, and it hosts a Global Learning Center for increasing attention. -

One Laptop Per Child: Vision Vs. Reality

contributed articles DOI:10.1145/1516046.1516063 Although some developing coun- The vision is being overwhelmed by the reality tries are indeed deploying OLPC lap- tops, others have cancelled planned of business, politics, logistics, and competing deployments or are waiting on the interests worldwide. results of pilot projects before decid- ing whether to acquire them in num- BY KENNETH L. KRAEMER, JASON DEDRICK, AND PRAKUL SHARMA bers. Meanwhile, the OLPC organiza- tion (www.olpc.com/) struggles with key staff defections, budget cuts, and ideological disillusionment, as it ap- pears to some that the educational One Laptop mission has given way to just getting laptops out the door. In addition, low- cost commercial netbooks from Acer, Asus, Hewlett-Packard, and other PC Per Child: vendors have been launched with great early success. So rather than distributing millions of laptops to poor children itself, OLPC Vision vs. has motivated the PC industry to devel- op lower-cost, education-oriented PCs, providing developing countries with low-cost computing options directly in Reality competition with OLPC’s own innova- tion. In that sense, OLPC’s apparent failure may be a step toward broader ANIEL ARCE, 12. OLPC, 13. CARLA DRAKE, 11. RODOLFO GOMEZ OLPC, 15. NIELS 14. MONROY, OLSON success in providing a new tool for children in developing countries. How- ever, it is also clear that the PC industry cannot profitably reach millions of the poorest children, so the OLPC objec- tives might never be achieved through AT THE WORLD Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, the commercial market alone. Here, we review and analyze the January 2005, Nicholas Negroponte unveiled the idea OLPC experience, focusing on the two of One Laptop Per Child (OLPC), a $100 PC that would most important issues: the successes transform education for the world’s disadvantaged and failures of OLPC in understand- ing and adapting to the developing- schoolchildren by giving them the means to teach country environment and the unex- themselves and each other. -

The Charisma of One Laptop Per Child's XO Laptop in Paraguay

Preprint copy - to appear in: Eden Medina, Ivan da Costa Marques, and Christina Holmes (eds.), Beyond Imported Magic: Essays on Science, Technology, and Society in Latin America. MIT Press, 2014. 10 Translating Magic: The Charisma of One Laptop per Child’s XO Laptop in Paraguay Morgan G. Ames In April 2008 liberal candidate Fernando Lugo won the Paraguayan presidency with 41 percent of the vote. It was the first time Paraguay’s conservative Colorado party had relinquished power in sixty-one years and one of the few peaceful transfers of power between parties in the country’s nearly two-hundred-year history (Nickson 2009). Known by his supporters as the “Bishop of the Poor” for his humanitarian service as a Catholic priest in one of Paraguay’s poorest districts, Lugo centered his campaign on reducing the nation’s bleak social inequalities and widespread corruption (Economist 2008; Nickson 2009). Lugo’s messages of hope and reform lasted beyond his election. During my fieldwork in 2010, many told me about their newfound hopes for Paraguay’s future on the 369 Preprint copy - to appear in: Eden Medina, Ivan da Costa Marques, and Christina Holmes (eds.), Beyond Imported Magic: Essays on Science, Technology, and Society in Latin America. MIT Press, 2014. world stage, even as Lugo became embroiled in scandal and faltered in implementing the dramatic changes he had promised (Economist 2009; Prensa Internacional 2009). Also in 2008, two elite, well-connected Paraguayans, both fresh out of college (one from Tufts University in Massachusetts, one from the Catholic University in Asunción), took up the banner of hope and steered it toward education.