1. Mr Speaker, I Thank Members for Speaking in Support of the Bill. They Have Also Raised Many Thoughtful Comments, Which I Will Now Address

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Active Learners Celebration 2016

FEI YUE NEWSLETTER • 2016 • JULY Together with Our Beneficiaries HEART@Fei Yue: Turning Families Around Together Active Learners Celebration 2016 Research Presentation on Transnational Families Executive Director’s Message ear Friends, It has been a busy yet fruitful quarter! DWe officially opened our Child Protection Specialist Centre, HEART@Fei Yue in April and had our Active Learners Celebration in May, in conjunction with Fei Yue’s 25th Anniversary this year. Through each of these events, we hope to reach out and bless even more beneficiaries through quality services, bringing transformation to their lives. In this issue, we also celebrate the journeys we have had the privilege to take together with the various beneficiaries that have come through our doors at different points of their lives. Each has a unique journey and a unique story to tell, and we hope that as you get a glimpse into their struggles, you too will be encouraged to reach out to those around you who are struggling and help them in your own unique way. May the years ahead bring even more meaningful and effective work in the community for Fei Yue! Leng Chin Fai Executive Director Greetings from Fei Yue Community Services (FYCS) and Fei Yue Family Whats Inside Service Centre (FYFSC). Footprints will Community Outreach Activities be published every quarter to bring to you highlights of what is up and Together ● 25 With Our Beneficiaries coming, what event you had missed Together with Our Beneficiaries and how you can partner with us in Services Quiz various ways. Looking Back Turning Families Around Together Active Learners Celebration 2016 Research Presentation on Transnational Families Coming Up Getting There www.fycs.org Tel: 65631106 Fax: 68199171 Community Outreach Activities Bukit Batok Zone 2 RC Mothers’ Day Celebration On 14 May, families from Bukit Batok RC Zone 2 came together for a heartwarming gathering in celebration of Mothers’ Day. -

1 Ministry of Law Committee of Supply 2017 Head R

MINISTRY OF LAW COMMITTEE OF SUPPLY 2017 HEAD R PARLIAMENT, 3 MARCH 2017 RESPONSE BY SENIOR MINISTER OF STATE FOR LAW, MS INDRANEE RAJAH SC Madam Chairman, 1. I will address the rest of the Members’ cuts. I. Ensure quality and sufficient legal industry manpower 2. To ensure that our legal industry continues to be vibrant and competitive internationally, the key stakeholders of the industry must actively embrace disruptive change and grasp the opportunities at hand. These include the private practitioners, in-house counsel, and law students. 3. The Working Group on Legal and Accounting Services under the Committee on the Future Economy which I co-chaired with Mr Chaly Mah was set up to identify growth areas and develop strategies for the legal sector’s growth and development. 4. The Working Group report will be released next month. It contains several key recommendations to position the Singapore legal and accounting services sector for the future, in particular the need to : (a) build thought leadership through driving standards and research; and 1 (b) equip legal professionals to be future-ready through deepening skillsets and industry expertise. 5. MinLaw will be working closely with the legal industry to achieve the outcomes envisaged in the recommendations. 6. Let me elaborate on our efforts in capability building. (a) Last year, we established the UniSIM School of Law to address the projected shortage of family and criminal practitioners in Singapore. (i) It took in its first cohort of 60 students in January 2017. (ii) 80% of the cohort are mature students with work and life experience and seeking a mid-career switch to law. -

Transcript of Budget 2017 Debate Round-Up Speech by Minister for Finance Heng Swee Keat on 2 March 2017

TRANSCRIPT OF BUDGET 2017 DEBATE ROUND-UP SPEECH BY MINISTER FOR FINANCE HENG SWEE KEAT ON 2 MARCH 2017 Table of Contents A. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 2 B. MEETING CHANGE HEAD-ON .......................................................................... 2 Addressing Concerns of Businesses ............................................................. 3 C. BUILDING OUR FUTURE ECONOMY – CAPABILITIES AND PARTNERSHIP 7 Our People – Going Beyond the Familiar .................................................... 10 Our Businesses – Creating Value and Bringing It to New Markets .............. 12 Forming Effective Partnerships in Our Economy ......................................... 15 D. VALUING OUR RESOURCES .......................................................................... 18 Changing Water Prices ................................................................................ 19 Introducing Carbon Tax ............................................................................... 21 Restructuring Diesel Taxes .......................................................................... 22 E. TOGETHER – A CARING AND INCLUSIVE SOCIETY .................................. 23 Building strong social foundations over the years ........................................ 23 Empowering the community ........................................................................ 25 F. ENSURING FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY FOR THE FUTURE ............................ 29 Fiscal Challenges -

Parliamentary Debates Singapore Official Report

Volume 94 Tuesday No 49 1 August 2017 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SINGAPORE OFFICIAL REPORT CONTENTS Written Answers to Questions Page 1. Guidelines and Avenues for Political Appointees to Address Allegations Publicly (Mr Chen Show Mao) 1 2. Increase in Total Number of Electors for Coming Presidential Election (Mr Gan Thiam Poh) 1 3. Efforts to Catalyse Reverse Mortgages for Private Housing (Mr Kwek Hian Chuan Henry) 1 4. Expected Run-in Period of New Signalling System on North-South Line (Mr Murali Pillai) 2 5. Minimum Age Requirement for Private Hire Car Drivers (Mr Sitoh Yih Pin) 3 6. Roadworthiness of CNG Vehicles (Miss Cheng Li Hui) 4 7. Vehicle Inspection Regime for CNG Taxis and Private Cars (Mr Ang Hin Kee) 4 8. Loss of Earnings by Taxi Drivers from Violent or Drunken Passengers (Assoc Prof Randolph Tan) 5 9. Applicants Granted PR Status under EDB's Global Investor Programme (Mr Gan Thiam Poh) 6 10. Publication of Information Forecasting Major Supply-Demand Mismatch in Specific Job Categories (Mr Pritam Singh) 6 11. Decline in Average Weekly Paid Overtime Hours Worked Per Employee (Assoc Prof Randolph Tan) 7 12. Errors in Tamil Translations on National Day Parade 2017 Rehearsal Collaterals (Mr Murali Pillai) 8 13. Plans for ASEAN to Execute Multilateral Approach on China's One Belt One Road Initiative (Mr Dennis Tan Lip Fong) 8 14. Recidivism of Local Inmates of Drug Rehabilitation Centres and Long-Term Imprisonment Regimes (Mr Louis Ng Kok Kwang) 9 15. Number of Local SMEs Owning Intellectual Property Rights (Mr Leon Perera) 10 16. -

Order Paper Supplement

FOURTEENTH PARLIAMENT OF SINGAPORE __________________ FIRST SESSION __________________________________ ORDER PAPER SUPPLEMENT ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Sup. No. 3 FRIDAY, 26 FEBRUARY 2021 1 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ESTIMATES OF EXPENDITURE FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 1ST APRIL 2021 TO 31ST MARCH 2022 (PAPER CMD 5 OF 2021) Notices of Amendments to be moved in the Committee of Supply. Head U - Prime Minister's Office That the total sum to be allocated for Head U of the Estimates be reduced by $100. (a) Smart Fight, Smart Nation Ms Tin Pei Ling (b) Digital Identity Ms Tin Pei Ling (c) Smart Nation and COVID-19 Mr Alex Yam Ziming (d) Smart Nation Private Sector Involvement Mr Alex Yam Ziming (e) Data Protocol and Safeguards Miss Cheng Li Hui (f) Smart Nation and Digital Government Group Ms Hany Soh (g) Smart Nation Ms Jessica Tan Soon Neo (h) Personalised Smart Nation Initiatives Mr Sharael Taha Sup. No. 3 2 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Head U - Prime Minister's Office - continued (i) E-payments Ms Jessica Tan Soon Neo (j) Option for PIN-only Bank Cards Mr Dennis Tan Lip Fong (k) Scams Involving Bank Customers Ms Sylvia Lim (l) Strengthening Anti-Money Laundering Efforts in Singapore -

Questions: Ms Joan Pereira: to Ask the Minister for the Environment

Questions: Ms Joan Pereira: To ask the Minister for the Environment and Water Resources (a) what measures will be implemented to help Singaporeans and residents cope with the worsening haze and air pollution; and (b) whether these measures will include the installation of air filter equipment in places frequented by the public, distribution of masks and public education on ways to minimise the impact on health. Mr Alex Yam Ziming: To ask the Minister for the Environment and Water Resources (a) how successful has the 2014 Transboundary Haze Pollution Act been in mitigating the annual threat of haze; (b) to date, how many successful cases have been investigated under the Act; (c) how many cases are currently under investigation; and (d) whether our neighbouring countries have been cooperative in providing assistance for investigation requests. Mr Alex Yam Ziming: To ask the Minister for the Environment and Water Resources in view of public feedback on the perceived "inaccuracies" of the 24-hr Pollutant Standards Index forecast currently used by NEA, whether the Ministry will consider adopting the hourly Air Quality Index now cast alongside the 1-hour PM2.5 concentration readings to assuage public concerns Mr Charles Chong: To ask the Minister for the Environment and Water Resources what is the number of companies and individuals who have been investigated and prosecuted under the Transboundary Haze Pollution Act since commencement of the Act in 2014. Mr Murali Pillai: To ask the Minister for the Environment and Water Resources (a) what steps has Singapore taken to promote the sustainable production of palm oil, pulp, paper and other commodities from plantations so as to disincentivise plantation owners and farmers from using the slash and burn method of clearing land that causes transboundary haze; and (b) what is the Ministry's assessment of the effectiveness of these steps. -

ASEAN Jubilee Meeting in Manila PM Lee on the Spirit of Singapore

Issue 33 11 August 2017 Click here for www.indiplomacy.com more on Sun Media PM Lee on the Spirit of Singapore n a departure from past telecast practice the Prime Minister’s National Day Message was delivered by PM Lee Hsien Loong with the Marina Bay as a backdrop to Ihighlight how Singapore’s successful development rests on not just tackling pressing issues of today but also addressing the challenges of the future - this he said was the Spirit of Singapore. The choice of the Bay East Garden, the eastern section of Gardens by the Bay location is also where the Singapore Founders Memorial will be sited. For the full text of his speech click here. Lecture S.T. Lee Distinguished Lecture of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, Singapore Co-chairing the ASEAN-China Post Ministerial Conference with PRC FM Wang Yi 12th July 2017 (Source: Dr Balakrishnan’s FB page) ASEAN Jubilee Meeting in Manila India, ASEAN and Changing Geoplolitics inister for Foreign Affairs Dr Vivian n Review ASEAN’s external relations and Balakrishnan attended the 50th exchange views on regional and international by Dr. S. Jaishankar Foreign Secre- ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ Meet- issues. tary, Ministry of External Affairs, Ming (AMM), Post-Ministerial Conferences (PMCs), 18th ASEAN Plus Three (APT) At the PMCs, the ASEAN FMs met their India to mark 25 years of India- Foreign Ministers’ Meeting (FMM), 7th East counterparts from ASEAN’s Dialogue Part- Singapore Partnership Asia Summit (EAS) FMM and 24th ASEAN ners (namely Australia, Canada, China, the Click here for transcript Regional Forum (ARF) in Manila, Philippines European Union, India, Japan, New Zealand, from 3 to 8 August 2017. -

Parliamentary Debates Singapore Official Report

Volume 94 Tuesday No 24 13 September 2016 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SINGAPORE OFFICIAL REPORT CONTENTS Written Answers to Questions for Oral Answer Not Answered by 3.00pm Page 31. Reconstruction of Novena Pedestrian Underpasses (Mr Melvin Yong Yik Chye) 1 32. Fostering Community Unity with SGSecure (Mr Christopher de Souza) 1 34. Action against Anti-social Neighbours (Mr Darryl David) 2 35. Popularity of Pre-fabricated Construction in Building Industry (Mr Alex Yam Ziming) 3 37. Thermal Comfort as Pre-requisite for Air-conditioned Spaces (Mr Louis Ng Kok Kwang) 4 38, 39. Accreditation and Licensing of Psychologists and Psychotherapists (Ms K Thanaletchimi ) 5 40. Take-up Rate for Home Access Plan to Aid Low-income Families with Internet Connectivity (Mr Murali Pillai) 6 42. Singapore's Financial Contribution to Support Syrian Refugees (Mr Louis Ng Kok Kwang) 7 43. Benefits and Allowances for Grassroots Leaders and Advisers (Mr Png Eng Huat) 8 44. New Benchmark for Madrasahs under New PSLE Scoring System (Mr Muhamad Faisal Bin Abdul Manap) 9 45. Security Measures for Primary and Secondary Schools in Light of Growing Terror Threat (Mr Melvin Yong Yik Chye) 9 46. Practice by Managed Care Companies for Doctors to Pay Administrative Fees for Referral of Patients (Mr Desmond Choo) 11 47. Subsidised or Free Health Screening Packages under MediShield Life (Ms Joan Pereira) 12 48. Impact of Indonesia's Plan to Stop Its Foreign Domestic Workers from Living in Singaporean Employers' Homes (Mr Melvin Yong Yik Chye) 14 51. Considerations behind Decision to Convert Coupon Parking to Electronic Parking Systems in Housing Estates (Mr Muhamad Faisal Bin Abdul Manap) 13 53. -

GE2020 Results

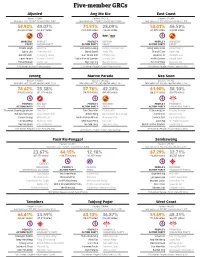

Five-member GRCs Aljunied Ang Mo Kio East Coast Electors: 150,821; Electors: 185,261; Electors: 121,644; total votes cast: 151,007; rejected votes: 5,009 total votes cast: 178,039; rejected votes: 5,009 total votes cast: 115,630; rejected votes: 1,393 59.93% 40.07% 71.91% 28.09% 53.41% 46.59% (85,603 votes) (57,244 votes) (124,430 votes) (48,600 votes) (61,009 votes) (53,228 votes) WORKERS’ PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S REFORM PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ PARTY ACTION PARTY ACTION PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY PARTY Pritam Singh Alex Yeo Lee Hsien Loong Kenneth Jeyaretnam Heng Swee Keat Abdul Shariff Sylvia Lim Chan Hui Yuh Darryl David Andy Zhu Cheryl Chan Dylan Ng Gerald Giam Chua Eng Leong Gan Thiam Poh Charles Yeo Jessica Tan Kenneth Foo Leon Perera Shamsul Kamar Nadia Ahmad Samdin Darren Soh Maliki Osman Nicole Seah Faisal Manap Victor Lye Ng Ling Ling Noraini Yunus Tan Kiat How Terence Tan 2015 winner: Workers’ Party (50.95%) 2015 winner: People’s Action Party (78.63%) 2015 winner: People’s Action Party (60.73%) Jurong Marine Parade Nee Soon Electors: 131,058; Electors: 139,622; Electors: 146,902; total votes cast: 125,400; rejected votes: 2,517 total votes cast: 131,630; rejected votes:1,787 total votes cast: 139,289; rejected votes: 2,199 74.62% 25.38% 57.76% 42.24% 61.90% 38.10% (91,692 votes) (31,191 votes) (74,993 votes) (54,850 votes) (86,219 votes) (53,070 votes) PEOPLE’S RED DOT PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ PEOPLE’S PROGRESS ACTION PARTY UNITED ACTION PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY SINGAPORE PARTY Tharman Shanmugaratnam Alec Tok Tan Chuan-Jin Fadli Fawzi K Shanmugam -

Shaping an Agile Workforce Together

Shaping an Agile workforce together. ANNUAL REPORT 2017/2018 ontents Page Foreword by Chairman and Chief Executive 2 Board Members and Committees 4 Organisation Chart 10 Senior Management 12 Key Achievements 14 (i) Developing Skills And Career Resilience In The Workforce (ii) Reducing Mismatches Between Workers And Jobs (iii) Ramping Up Outreach Campaigns Of Adapt And Grow (A&G) Programmes (iv) Supporting Industry Transformation For Better Careers (v) Sustaining A High-Performing And Engaged WSG Highlights 21 Plans For The Next Fiscal Year 32 Financial Statements 37 Foreword by Chairman and Chief Executive By Chairman 2017 was an exciting year for Workforce Singapore (WSG). The Singapore economy continued to transform amidst technological disruption. WSG focused efforts to create an agile workforce with a strong Singaporean core. Initiatives were ramped up to help workers take greater ownership of their careers and pick up new and relevant skills. Programmes were also enhanced to drive greater inclusivity in hiring, and to facilitate smoother job matches and transitions. These are all part of ongoing endeavours to help businesses and workers navigate the uncertain economic climate. Mr Lim Ming Yan, Chairman 2 Foreword by Chairman and Chief Executive In particular, WSG sought to bridge the gap to facilitate smoother job matches and transitions. The Professional Conversion Programme, Work Trial and Career Support Programme were all enhanced to align more closely with jobseeker and employer needs. The Lean Enterprise Development scheme gained further traction with more companies taking on job redesign projects to become more manpower lean. WSG also introduced the rebranded Careers Connect to offer jobseekers an expanded suite of customised career matching services. -

Reply to Parliamentary Question on Crypto Asset Market

Parliamentary Replies Published Date: 05 April 2021 Reply to Parliamentary Question on Crypto Asset Market QUESTION NO 869 NOTICE PAPER 348 OF 2021 FOR WRITTEN ANSWER Date: For Parliament Sitting on 5 April 2021 Name and Constituency of Member of Parliament Mr Desmond Choo, MP, Tampines GRC Question: To ask the Prime Minister (a) how large is the crypto asset market in Singapore; (b) how does MAS view the trend of greater transactions of such assets amongst companies and retail investors; and (c) how are crypto asset exchanges regulated to provide a stable and benign trading environment in Singapore. Answer by Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Senior Minister and Minister in charge of MAS: 1. Mr Speaker, Mr Murali Pillai has also filed a similar PQ for the next Sitting [1] . My response today will cover the questions raised by both Mr Desmond Choo and Mr Murali Pillai. 2. There are two common types of crypto assets. First, cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, which may be used for payment purposes. Second, securities tokens, which are digital representations of traditional securities such as shares and bonds. The risks posed by each type are different and so are our regulatory approaches. 3. Cryptocurrencies can be highly volatile, as their value is typically not related to any economic fundamentals. They are hence highly risky as investment products, and certainly not suitable for retail investors. MAS has issued numerous consumer advisories to warn the public of the risks of trading these products. 4. The size of the cryptocurrency market in Singapore remains small compared to, say, shares and bonds. -

Ministry of Finance Committee of Supply Debate 2017

MINISTRY OF FINANCE COMMITTEE OF SUPPLY DEBATE 2017 SPEECH BY SENIOR MINISTER OF STATE (FINANCE) A. ACCOUNTABILITY Office of Budgetary Responsibility A1 Madam Chairperson, Mr Low Thia Khiang suggested that we set up an independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), such as those in other countries, and he referred specifically to the OBR in the UK. A2 While it is always useful to look at what other countries do, it is important to remember that what is done in one country is not always necessary or relevant to another. In determining whether to adopt institutions similar to those elsewhere, it is also important to understand the context in which those institutions were established. A3 The OBR was set up in the UK in 2010. And the context in which it was set up was as follows: 1 a. The new Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government had just taken over from the Labour government after the general election. They were burdened by a huge deficit inherited from the previous government. There was little confidence in government economic and fiscal planning. b. This can be seen from the speech of the then Chancellor, Mr George Osborne, when he announced the setting up of the OBR. This is what he said: c. “So today, less than a week after taking office, I want to explain some of the early arrangements for dealing with the fiscal crisis left by the last Government. First, let me just tell you some of the stark facts. Last year, our budget deficit was the largest ever it has been in our peacetime history.