State Politics & Policy – Voter Registration in Florida the Effects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Florida 2004

This story was edited and ready to run when I happened to mention to my editor, John Bennet, that I’d spent the afternoon hanging Kerry literature on doorknobs. Twenty minutes later, I got a call from both Bennet and David Remnick, telling me they had to kill the story because of my obvious bias. “What would happen if Fox News found out?” Remnick asked, to which I replied, “What would happen if The Nation found out that the New Yorker killed a good story because it was afraid of Fox News?” I argued that I was not a paid operative of the Kerry campaign, but just a citizen participating in democracy. And if they couldn’t trust me to keep my politics out of my writing, how could they trust me to be on staff at all? It’s conversations like this that explain why I don’t write for the New Yorker anymore. Dan Baum 1650 Lombardy Drive Boulder, CO 80304 (303) 546-9800 (303) 917-5024 mobile [email protected] As the third week of September began in south Florida, the air grew torpid and heavy with menace. Hurricane Ivan was lurking south of Cuba, trying to decide whether to punish the Sunshine State with a third tropical lashing in as many weeks. Palm trees along Biscayne Boulevard rustled nervously. The sky over Miami swelled with greenish clouds that would neither dissipate nor burst. Election day was fifty-six days off, and Florida’s Democrats anticipated it with an acute and complex dread. The presidential Florida.18 Created on 10/1/04 5:32 AM Page 2 of 25 contest in Florida is as close this year as it was in 2000,1 which raises the specter of another fight over whether and how to recount votes. -

Democracy Restoration Act of 2009 Hearing Committee

DEMOCRACY RESTORATION ACT OF 2009 HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON H.R. 3335 MARCH 16, 2010 Serial No. 111–84 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 55–480 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:37 Jun 09, 2010 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\CONST\031610\55480.000 HJUD1 PsN: 55480 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California MAXINE WATERS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia STEVE COHEN, Tennessee STEVE KING, Iowa HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., TRENT FRANKS, Arizona Georgia LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas PEDRO PIERLUISI, Puerto Rico JIM JORDAN, Ohio MIKE QUIGLEY, Illinois TED POE, Texas JUDY CHU, California JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TOM ROONEY, Florida TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin GREGG HARPER, Mississippi CHARLES A. -

Grassroots, Geeks, Pros, and Pols: the Election Integrity Movement's Rise and the Nonstop Battle to Win Back the People's Vote, 2000-2008

MARTA STEELE Grassroots, Geeks, Pros, and Pols: The Election Integrity Movement's Rise and the Nonstop Battle to Win Back the People's Vote, 2000-2008 A Columbus Institute for Contemporary Journalism Book i MARTA STEELE Grassroots, Geeks, Pros, and Pols Grassroots, Geeks, Pros, and Pols: The Election Integrity Movement's Rise and the Nonstop Battle to Win Back the People's Vote, 2000-2008 Copyright© 2012 by Marta Steele. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. For information, address the Columbus Institute for Contemporary Journalism, 1021 E. Broad St., Columbus, Ohio 43205. The Columbus Institute for Contemporary Journalism is a 501(c) (3) nonprofit organization. The Educational Publisher www.EduPublisher.com BiblioPublishing.com ISBN:978-1-62249-026-4 ii Contents FOREWORD By Greg Palast …….iv PREFACE By Danny Schechter …….vi INTRODUCTION …….ix By Bob Fitrakis and Harvey Wasserman ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …...xii AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION …..xix CHAPTER 1 Origins of the Election ….….1 Integrity Movement CHAPTER 2A Preliminary Reactions to ……..9 Election 2000: Academic/Mainstream Political CHAPTER 2B Preliminary Reactions to ……26 Election 2000: Grassroots CHAPTER 3 Havoc and HAVA ……40 CHAPTER 4 The Battle Begins ……72 CHAPTER 5 Election 2004 in Ohio ……99 and Elsewhere CHAPTER 6 Reactions to Election 2004, .….143 the Scandalous Firing of the Federal -

Elections Cover-Up 3/1/18, 8�46 PM

Elections Cover-up 3/1/18, 846 PM Elections Cover-up A Two-Page Summary of Revealing Media Reports With Links The concise excerpts from media articles below reveal major problems with the elections process. This is not a partisan matter. Fair elections are crucial to all who support democracy. Few have compiled this information in a way that truly educates the public on the great risk of using electronic voting machines. Spread the word and be sure to vote. MSNBC News, 9/28/11, It only takes $26 to hack a voting machine Researchers from the Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois have developed a hack that, for about $26 and an 8th-grade science education, can remotely manipulate the electronic voting machines used by millions of voters all across the U.S. Researchers ... from Argonne National Laboratory's Vulnerability Assessment Team demonstrate three different ways an attacker could tamper with, and remotely take full control, of the e-voting machine simply by attaching what they call a piece of "alien electronics" into the machine's circuit board. The $15 remote control ... enabled the researchers to modify votes from up to a half-mile away. CNN News, 9/20/06, Voting Machines Put U.S. Democracy at Risk Electronic voting machines...time and again have been demonstrated to be extremely vulnerable to tampering and error. During the 2004 presidential election, one voting machine...added nearly 3,900 additional votes. Officials caught the machine's error because only 638 voters cast presidential ballots. In a heavily populated district, can we really be sure the votes will be counted correctly? A 2005 Government Accountability Office report on electronic voting confirmed the worst fears: "There is evidence that some of these concerns have been realized and have caused problems with recent elections, resulting in the loss and miscount of votes." New York Times, 9/5/06, In Search of Accurate Vote Totals A recent government report details enormous flaws in the election system in Ohio's biggest county, problems that may not be fixable before the 2008 election. -

In the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA NORTH CAROLINA STATE CONFERENCE ) OF THE NAACP; EMMANUEL BAPTIST ) CHURCH; COVENANT PRESBYTERIAN ) CHURCH; BARBEE’S CHAPEL MISSIONARY ) BAPTIST CHURCH, INC.; ROSANELL ) EATON; ARMENTA EATON; CAROLYN ) COLEMAN; JOCELYN FERGUSON-KELLY; ) FAITH JACKSON; MARY PERRY; and ) MARIA TERESA UNGER PALMER, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) 1:13CV658 ) PATRICK LLOYD MCCRORY, in his ) official capacity as Governor of ) North Carolina; KIM WESTBROOK ) STRACH, in her official capacity ) as Executive Director of the ) North Carolina State Board of ) Elections; RHONDA K. AMOROSO, ) in her official capacity as ) Secretary of the North Carolina ) State Board of Elections; JOSHUA ) D. MALCOLM, in his official ) capacity as a member of the North ) Carolina State Board of Elections; ) JAMES BAKER, in his official ) capacity as a member of the North ) Carolina State Board of Elections; ) and MAJA KRICKER, in her official ) capacity as a member of the North ) Carolina State Board of Elections, ) ) Defendants. ) __________________________________ ) LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS OF NORTH ) CAROLINA; A. PHILIP RANDOLPH ) INSTITUTE; UNIFOUR ONESTOP ) COLLABOARATIVE; COMMON CAUSE NORTH ) CAROLINA; GOLDIE WELLS; KAY ) BRANDON; OCTAVIA RAINEY; SARA ) STOHLER; and HUGH STOHLER, ) Case 1:13-cv-00861-TDS-JEP Document 420 Filed 04/25/16 Page 1 of 485 ) Plaintiffs, ) ) and ) ) LOUIS M. DUKE; ASGOD BARRANTES; ) JOSUE E. BERDUO; CHARLES M. GRAY; ) NANCY J. LUND; BRIAN M. MILLER; ) BECKY HURLEY MOCK; MARY-WREN ) RITCHIE; LYNNE M. WALTER; and ) EBONY N. WEST, ) ) Plaintiff-Intervenors, ) ) v. ) 1:13CV660 ) THE STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA; ) JOSHUA B. HOWARD, in his official ) capacity as a member of the State ) Board of Elections; RHONDA K. -

Black Box Voting Report

330 SW 43rd St Suite K PMB-547 Renton WA 98055 425-793-1030 – [email protected] http://www.blackboxvoting.org The Black Box Report SECURITY ALERT: July 4, 2005 Critical Security Issues with Diebold Optical Scan Design Prepared by: Harri Hursti [email protected] Special thanks to Kalle Kaukonen for pre-publication review On behalf of Black Box Voting, Inc. A nonprofit, nonpartisan, 501c(3) consumer protection group for elections Executive Summary The findings of this study indicate that the architecture of the Diebold Precinct-Based Optical Scan 1.94w voting system inherently supports the alteration of its basic functionality, and thus the alteration of the produced results each time an election is prepared. The fundamental design of the Diebold Precinct-Based Optical Scan 1.94w system (AV OS) includes the optical scan machine, with an embedded system containing firmware, and the removable media (memory card), which should contain only the ballot box, the ballot design and the race definitions, but also contains a living thing – an executable program which acts on the vote data. Changing this executable program on the memory card can change the way the optical scan machine functions and the way the votes are reported. The system won’t work without this program on the memory card. Whereas we would expect to see vote data in a sealed, passive environment, this system places votes into an open active environment. With this architecture, every time an election is conducted it is necessary to reinstall part of the functionality into the Optical Scan system via memory card, making it possible to introduce program functions (either authorized or unauthorized), either wholesale or in a targeted manner, with no way to verify that the certified or even standard functionality is maintained from one voting machine to the next. -

EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Mitchell Block James Fadiman

Direct Cinema Limited in association with Abramorama & Mitropoulous Films presents a Concentric Media production STEALING AMERICA: Vote by Vote Narrated by Peter Coyote Directed & Produced by Dorothy Fadiman Production Notes 90 Minutes, Color, 35 mm www.StealingAmericaTheMovie.com www.StealingAmericaTheMovie.com/GetActive PUBLIC RELATIONS DISTRIBUTION: PUBLIC RELATIONS LOS ANGELES Direc t Cinema Limited NEW YORK Fredell Pogodin & Associates P.O. Box 10003 Falco Ink Office: (323) 931 7300 Santa Moni ca, CA 90410 Office: (212) 445 7100 Fredell Pogodin Office: (31 0) 636 8200 Mobile: (917) 225 7093 [email protected] Fax: (310 ) 636 8228 Shanno n Tre usch Bradley Jones Mitchell Block [email protected] [email protected] mw block@ gmail.c om Steven Beeman Kierste n Jo hnson [email protected] [email protected] BOOKING INFORMATION: BOOKING INFORMATION: WEST & NATIONAL EAST & NATIONAL Mitropoulos Films Abramorama Office: (310) 273 1444 Office: (914) 273 9545 Mobile: (310) 567 9336 Mobile: (917) 566 7175 MJ Peckos Richard Abramowitz [email protected] [email protected] Direct Cinema Limited, P.O. Box 10003, Santa Monica, California Phone (310) 636-8200; E-Mail: [email protected] CREDITS PRODUCER & DIRECTOR Dorothy Fadiman NARRATOR Peter Coyote MUSIC Laurence Rosenthal EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Mitchell Block James Fadiman CO-PRODUCERS Bruce O'Dell Carla Henry VIDEOGRAPHY Matthew Luotto & Rick Keller PRINCIPAL EDITORS Katie Larkin Matthew Luotto Xuan Vu Ekta Bansal Bhargava CONSULTING EDITORS Pam Wise, A.C.E. Kristin Atwell ASSISTANT EDITORS Roopa Parameswaran & Joanne Dorgan MOTION GRAPHICS Digital Turbulence Douglas DeVore & Wendy Van Wazer Laura Green & Matthew Luotto ADDITIONAL VIDEOGRAPHY Fletcher Holmes, Mike Kash, Jim Heddle, Steve Longstreth, Andy Dillon, David Frenkel William Brandon Jourdan, Domenica Catalano ASSOCIATE PRODUCERS Katie Larkin Robert Carrillo Cohen James Q. -

April 4, 2006

BOARD OF SUPEftVlSORS 200~Ej,n 2~~p 2: 1 q March 22, 2006 Dear & &+d w In light of the lawsuit just filed (see attached) against the purchase and use of Diebold touchscreen DREs (Direct Record Electronic) in the state of California, I am counting on you to find alternative systems for use in this year's elections. The Diebold touchscreen DREs were already decertified once on ample evidence in 2004, and the stack of evidence against their use has only grown since that time. It would be irresponsible for your county to commit taxpayer dollars and citizen votes to these failing machines under such uncertain conditions. The Secretary of State made it clear in his conditional certification of the Diebold TSX that he is passing responsibility off to the counties, and to the vendors. In lay terms, our Secretary of State is leaving you "holding the bag." Please choose another option that voters can actually trust, the disability community can access, and taxpayers can stomach. As a taxpayer, I am concerned about the irresponsible cost to counties that these touchscreen DREs represent. According to one seasoned Election Chief in Florida, Ion Sancho, it will cost him $1.8 million to adequately serve his county on paper ballots optically scanned, in combination with a ballot-marking device to meet the disability access requirements of the Help America Vote Act. To provide the same voter capacity for his county using touchscreen DREs, Mr. Sancho would have to spend $5 million. This may make sense to the vendors, but it certainly doesn't make sense to our a1reab.y strapped county budgets. -

Democratic Club Leadership, on Jan 16, 2017, the Santa Clara

Democratic Club Leadership, On Jan 16, 2017, the Santa Clara County Democratic Club approved the attached resolution calling for our Democratic Party “to aggressively press for changes needed to achieve more democratic voting procedures”. In other words, stop ignoring voter suppression and rigged vote-counting machines, and start doing something about both. During discussion of the Resolution, most people acknowledged that voter suppression was widespread. However, many questioned the rigging of vote-counting machines. In response to those doubters, the following supplemental information was compiled. – “Red Shift” is the tendency of voting-counting machines to report more votes for the Republican candidates than the exit polls predict. Anecdotal stories of friends/relatives who, rather than simply refuse to answer an exit poll, chose to lie to pollsters raises this question: Why doesn't that happen in other countries where exit polls are considered the "gold standard"? And if Trump voters are such liars, does that also apply to Hillary's voters during the primary. If so that would explain the "red shift" that propelled her to victory in the 2016 Primaries in Red states. Find the details in the analysis of the Democratic primaries from Axel Geijsel of Tilburg University (The Netherlands) and Rodolfo Cortes Barragan of Stanford University (U.S.A.). On the 4th/last page is a chart followed by an Appendix link. The graphic below (from page 3 of that Appendix) shows how red shift affected Clinton’s votes. Here’s the (funny) Redacted video -

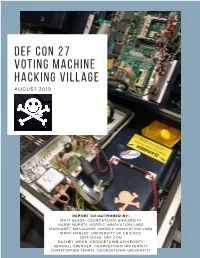

DEF CON 27 Voting Machine Hacking Village Report

DEF CON 27 Voting Machine Hacking Village AUGUST 2019 REPORT CO-AUTHORED BY: MATT BLAZE, GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY HARRI HURSTI, NORDIC INNOVATION LABS MARGARET MACALPINE, NORDIC INNOVATION LABS MARY HANLEY, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO JEFF MOSS, DEF CON RACHEL WEHR, GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY KENDALL SPENCER, GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY CHRISTOPHER FERRIS, GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY Table of Contents Foreword: Senator Ron Wyden 3 Introduction 5 Executive Summary 6 Equipment Available at the Voting Village 10 Overview of Technical Issues Found or Replicated by Participants 13 ES&S ExpressPoll Tablet Electronic Pollbook 13 ES&S AutoMARK 16 Dominion Imagecast Precinct 20 AccuVote-OS Precinct Count 22 EVID 24 ES&S M650 25 Recommendations 26 DARPA Secure Hardware Technology Demonstrator 28 Conclusion 29 Concluding Remarks: Representative John Katko 30 Afterword: Representative Jackie Speier 33 Acknowledgments 35 Appendix A: Voting Village Speaker Track 36 PagePage 3 2 FOREWORD BY SENATOR RON WYDEN there will still be time to dramatically improve our election security by 2020. The House has already passed a bill to ensure every voter can vote with a hand-marked paper ballot. And the Senate companion to the SAFE Act does even more to secure every aspect of our election infrastructure. The danger is real. The solutions are well-known and overwhelmingly supported by the public. And yet the Trump Administration and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell refused to take any meaningful steps to secure our elections. It’s an appalling dereliction of duty that leaves American democracy at risk. These politicians need to hear the message that Americans won’t accept doing nothing as the response to the serious threat of foreign interference in our elections. -

When Combatting Voter Fraud Leads to Voter Suppression by Phyllis Raybin Emert

A PUBLICATION OF THE NEW JERSEY STATE BAR FOUNDATION WINTER 2012 • VOL. 11, NO. 2 A NEWSLETTER ABOUT LAW AND DIVERSITY When Combatting Voter Fraud Leads to Voter Suppression by Phyllis Raybin Emert With the presidential election fast approaching in In addition, the report revealed that “of the 12 likely November, it is important to remember that taking battleground states [in the 2012 presidential election], part in America’s democratic process by casting according to The Los Angeles Times analysis in August, your vote is a fundamental right of every American five have already cut back on voting rights and two more of voting age. Proposed legislation in as many as are currently considering new restrictions.” According 38 states could make it harder for some Americans to the Brennan Center’s report and other newspaper to exercise that right. accounts, some of the voting restrictions include making According to a report released in October 2011, it more difficult to register to vote, cutting back on more than five million eligible voters will find it harder early voting, a huge benefit for millions of Americans to cast their ballots in November if these states pass who cannot take off work >continued on page 2 their proposed legislation. The report, titled “Voting Law Changes in 2012,” was produced by New York University School of Law’s Brennan Center for Justice, Wal-Mart Wins, A Million Women Lose a non-partisan, public policy and law by Cheryl Baisden institute that focuses on the fundamental In 1963, the United States passed the Equal Pay Act, making issues of democracy and justice. -

STEALING AMERICA Vote by Vote Time Speaker Dialog Code 0:00:07 NARRATOR "The Right to Vote...Is the Primary Right by Which Other Rights Are Protected,” THOMAS PAINE

STEALING AMERICA Vote by Vote Time Speaker Dialog Code 0:00:07 NARRATOR "The right to vote...is the primary right by which other rights are protected,” THOMAS PAINE 0:00:32 GREG PALAST The nasty little secret of American democracy, and we're not INVESTIGATIVE supposed to talk about this, is that not all the ballots get REPORTER counted. BBC AND THE GUARDIAN (UNITED KINGDOM) 0:00:44 PAT LEAHAN The poll workers watched a 100 and some people go in, DIRECTOR PEACE AND specifically to that booth and vote. At the end of the day, JUSTICE CENTER when that tape came out, one person had voted, according LAS VEGAS, NEW to the machine. MEXICO 0:00:57 ROBERT STEINBACK People, they should be talking about this, not from the JOURNALIST standpoint of you’re liberal, and you’re conservative, and, THE MIAMI HERALD you know, which side of the fence are you on. The issue is: If FLORIDA it was tainted once, it can be tainted again. 0:01:18 NARRATOR It is critical that all qualified voters are able to vote and that all votes are counted as cast. There is growing evidence that eligible citizens are being denied the right to vote and that votes, when cast, may be lost or miscounted or even deleted. Until recently, most Americans have assumed that our elections are basically honest. But with each election, more and more people are reporting incidents of voter suppression and irregular tallies. At first, machine problems were dismissed as “glitches,” and difficulties faced by voters were simply the result of poor planning and poll worker error.