Children's Attitudes Toward the Electoral Process and the '92 Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kids Elect President Barack Obama the Winner in Nickelodeon's Kids Pick the President "Kids' Vote" National Poll

Kids Elect President Barack Obama The Winner In Nickelodeon's Kids Pick the President "Kids' Vote" National Poll More Than Half a Million Votes Cast NEW YORK, Oct. 22, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- The kids of the United States have spoken and President Barack Obama has been elected the winner of Nickelodeon's 2012 Kids Pick the President "Kids' Vote." Since it began in 1988, kids have correctly picked the winner (in advance of the national election) five out of the last six times. More than half a million votes were cast in the network's online poll as part of Nickelodeon's Kids Pick the President initiative to build young citizens' awareness of, and involvement in, the election process. President Obama received 65% of the vote and former Governor Mitt Romney received 35%. In order to more closely replicate the actual election, and to ensure the results were more authentic, this year the voting was limited to one vote per electronic device. Kids were able to cast their votes online from Oct. 15 to Oct. 22. On Monday, Oct. 22, at 7:30 p.m. (ET/PT), Linda Ellerbee, the Emmy Award-winning host of Nickelodeon's Nick News, will announce the winner of the Kids Pick the President "Kids' Vote" on the network. "What politicians do definitely affects kids but for me, it's not about who wins," said Ellerbee. "It's about creating tomorrow's voters. Democracy takes work. We're the practice field." Leading up to the Kids Pick the President online vote, Nickelodeon aired two election-themed Nick News with Linda Ellerbee specials this year, which ranked as the series' highest-rated episodes for 2012 to date. -

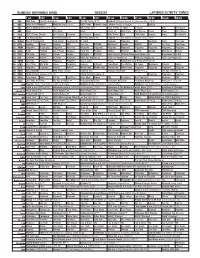

Sunday Morning Grid 10/25/20 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/25/20 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Tennessee Titans. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å NBC4 News Premier League Soccer: Wolves vs Magpies IndyCar 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch AAA Sex Abuse 7 ABC News This Week News Hearts of Rock-Park Sea Rescue Ocean News MLS Soccer 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb AAA 1908 Gold Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Green Bay Packers at Houston Texans. (N) Å 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Kenmore Medicare AAA Medicare News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Cooking Tummy Cooking AAA Paid Prog. BISSELL Bathroom? Organic WalkFit! AAA Paid Prog. Can’tHear 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Programa Más Pelo Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Queens Scratch Milk Street Nevens 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Curious Curious Highlights Biz Kid$ Suze Orman’s Ultimate Retirement Guide (TVG) Riverdance 25th Ann 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Medicare NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Aquí y ahora Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) 4 0 KTBN Dr. -

US President

US President Americans are about to go to the polls to decide who will be the next President of the United States. But what does it mean to be President and what do the candidates think about particular issues? EPISODE 31 4TH NOVEMBER 2008 Focus Questions Learning Area 1. Who are the presidential candidates? Society and Environment 2. Why is the President of the United States sometimes called `the world’s most powerful person’? 3. How many Presidents have there been? Key learning 4. Who can run for presidency? Students will investigate the 5. Who is responsible for protecting the President? candidates for the US 6. Why do they need protection? presidential election and 7. Describe the White House. their position on certain 8. What was surprising about this story? issues. 9. Do you think Australia should be concerned about what happens in the US election? Explain your answer. 10. How has your thinking changed after watching the BtN story? Meet the candidates Students will be investigating the candidates running in the US election. Ask students to brainstorm what they already know about the candidates and what they would like to find out. Students will be using the Internet to research who the candidates are and what each stands for on particular issues. Encourage students to choose issues they think are important. The following can be used as a guide: • Environment • Education • Health care • Immigration Students need to: • Summarise what each candidate’s position is on the issues. • Explain the similarities and differences between the views of the Democrats and Republicans. -

Televised Debates: Candidates Take a Stand

Televised Debates: Candidates Take a Stand Topic: Televised Debates Grade Level: Grades 3 – 6 Subject Area: Media Literacy, Social Studies, Language Arts Time Required: 3 class periods Goals/Rationale The 1960 debates between John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon are historically significant because they were the first live televised presidential debates and they had great impact on voters in a close election. As students investigate a historic event from the 1960 presidential campaign, they will learn how political debates help voters select a candidate for office. Essential Question: What criteria should voters use to select a leader? Objectives Students will be able to: identify important elements of a debate, such as taking a stand on an issue. describe the importance of the 1960 debates. identify information viewers can learn about a candidate from a televised debate. determine and describe important criteria for selecting a candidate. Connections to Curriculum (Standards) National Standards for Civics and Government V: What are the Roles of the Citizen in American Democracy? National History Standard 3: Historical Analysis and Interpretation NCTE/IRA Standards for the English Language Arts 4, 5, 6 Prior Knowledge It is helpful for students to have an understanding of the electoral process before implementing this lesson. Preview these vocabulary words: Candidate Campaign Debate Poll Election Historical Background and Context During the fall of 1960, polls showed that Senator John F. Kennedy and Vice-President Richard Nixon were in a very tight race to become president of the United States. Although still recovering from knee surgery, Nixon dashed from state to state, hoping to fulfill his campaign Prepared by the Department of Education and Public Programs, John F. -

US President 1. Who Are the Presidential Candidates?

EPISODE 31 US President 4TH NOVEMBER 2008 1. Who are the presidential candidates? 2. Why is the President of the United States sometimes called `the world’s most powerful person’? 3. How many Presidents have there been? 4. Who can run for presidency? 5. Who is responsible for protecting the President? 6. Why do they need protection? 7. Describe the White House. 8. What was surprising about this story? 9. Do you think Australia should be concerned about what happens in the US election? Explain your answer. 10. How has your thinking changed after watching the BtN story? Investigate how the candidates have used the Internet to campaign for the presidency. Phone fears 1. Briefly summarise the BtN phone fears story. 2. Describe the importance of mobile phones in Australia. 3. Explain in your own words how a mobile phone works. 4. What else emits radio waves? 5. What is the health concern associated with mobile phones? 6. Why can’t scientists agree on how safe mobile phones are? 7. Why do some scientists say that children under sixteen are at increased risk? 8. What do they recommend children do to use mobile phones safely? 9. Has your thinking about mobile phone safety changed after watching the BtN story? Why or why not? 10. Do you think the benefits of using mobile phones outweigh the potential risks? Explain your answer. Brainstorm text messaging language. What codes do people use for texting? Create a text message using code and ask another student to decipher it. Apprentice jockeys 1. Write a brief outline of the BtN story. -

Media Literacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Media Literacy

Media Literacy This page intentionally left blank Media Literacy Keys to Interpreting Media Messages FOURTH EDITION Art Silverblatt, Andrew Smith, Don Miller, Julie Smith, and Nikole Brown Copyright 2014 by Art Silverblatt All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Silverblatt, Art. Media literacy : keys to interpreting media messages / Art Silverblatt, Andrew Smith, Don Miller, Julie Smith, and Nikole Brown. — Fourth edition. pages cm Includes index. ISBN 978-1-4408-3091-4 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-4408-3092-1 (e-book) — ISBN 978-1-4408-3115-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Media literacy. I. Title. P96.M4S594 2014 302.23—dc23 2014001562 ISBN: 978-1-4408-3091-4 (cloth) 978-1-4408-3115-7 (paper) EISBN: 978-1-4408-3092-1 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. Praeger An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America To my Media Literacy Buddies: • Respected ML scholars and colleagues: Frank Baker, Liz Thoman, Kathleen Tyner, Renee Hobbs, and Marieli Rowe • Partners: Yupa Saisanan Na Ayudhya, Sara Gabal, Kit Jenkins, Jessica Brown, and my DIMLE co-authors • My young ML scholars: Zoey Wong, Ahmed (Naz) Nasr El Din, Naoko Onishi, Bobbie Watson, and Chris Penberthy • The co-authors of this fourth edition: Julie Smith, Andrew A. -

Barrett Confirmed As Supreme Court Justice by Deeply Divided Senate

NATION: Standoff imperils jobless, small businesses A3 TUESDAY, OCTOBER 27, 2020 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 $1.00 Barrett confirmed as Supreme Court justice by deeply divided Senate BY LISA MASCARO conservative court majority for years lidify the court’s rightward tilt. COVID-19. His vote was not necessary. AP Congressional Correspondent to come. Monday’s 52-48 vote was the closest With Barrett’s confirmation as- Trump’s choice to fill the vacancy of high court confirmation ever to a sured, Trump was expected to cele- WASHINGTON — Amy the late liberal icon Ruth Bader Gins- presidential election, and the first in brate with a primetime swearing-in Coney Barrett was con- burg potentially opens a new era of modern times with no support from event at the White House. Justice Clar- firmed to the Supreme rulings on abortion, the Affordable the minority party. The spiking ence Thomas was set to administer Court late Monday by a Care Act and even his own election. COVID-19 crisis has hung over the the Constitutional Oath, a senior deeply divided Senate, Democrats were unable to stop the proceedings. Vice President Mike White House official said. Republicans overpower- outcome, Trump’s third justice on the Pence’s office said Monday he would “This is something to be really ing Democrats to install BARRETT court, as Republicans race to reshape not preside at the Senate session un- proud of and feel good about,” Senate President Donald the judiciary. less his tie-breaking vote was needed Majority Leader Mitch McConnell Trump’s nominee days Barrett is 48, and her lifetime ap- after Democrats asked him to stay before the election and secure a likely pointment as the 115th justice will so- away when his aides tested positive for SEE BARRETT, PAGE A6 Large events in S.C. -

Rethinking the Children's Television Act for a Digital

S. HRG. 111–485 RETHINKING THE CHILDREN’S TELEVISION ACT FOR A DIGITAL MEDIA AGE HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JULY 22, 2009 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 56–408 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 07:17 Jun 29, 2010 Jkt 056408 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\WPSHR\GPO\DOCS\56408.TXT SCOM1 PsN: JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia, Chairman DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas, Ranking JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada BARBARA BOXER, California JIM DEMINT, South Carolina BILL NELSON, Florida JOHN THUNE, South Dakota MARIA CANTWELL, Washington ROGER F. WICKER, Mississippi FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia MARK PRYOR, Arkansas DAVID VITTER, Louisiana CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota MEL MARTINEZ, Florida TOM UDALL, New Mexico MIKE JOHANNS, Nebraska MARK WARNER, Virginia MARK BEGICH, Alaska ELLEN L. DONESKI, Chief of Staff JAMES REID, Deputy Chief of Staff BRUCE H. ANDREWS, General Counsel CHRISTINE D. KURTH, Republican Staff Director and General Counsel BRIAN M. HENDRICKS, Republican Chief Counsel (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 07:17 Jun 29, 2010 Jkt 056408 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\WPSHR\GPO\DOCS\56408.TXT SCOM1 PsN: JACKIE C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on July 22, 2009 .............................................................................. -

New Digital Media, Social Institutions and the Changing Roles of Youth

New Digital Media, Social Institutions and the Changing Roles of Youth Margaret Weigel Katie Davis Carrie James Howard Gardner TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................2 New Media and Youth ............................................................................2 Research Perspective .............................................................................3 Research Methodology ...........................................................................4 I. The Changing Roles of the Student ................................................................6 Introduction......................................................................................................6 a. Schools, students and Social Development...............................................6 Students and Social Development........................................................... 6 The Student-Student Relationship........................................................... 7 The Student-Teacher Relationship.......................................................... 7 The Student-Institution Relationship....................................................... 8 b. NDM, students and social behavior..........................................................9 c. NDM, students and social behavior -- implications ..................................9 Reconsidering Attention......................................................................... 9 * Cellphones ........................................................................... -

Wellborn Man Arrested in Teen's Death

A3 SATURDAY/SUNDAY, OCT. 31-NOV. 1, 2020 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $2 WEEKEND EDITION Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM SUNDAY + PLUS >> FOOTBALL FOOTBALL Sweat named Tigers top Branford Lake City’s Chargers in holds off thriller for Trenton new assistant first win late 6B city manager Sean of the South SEE 2A SEE 12A SEE 12A Wellborn man arrested in teen’s death Salt Life co-founder ers at Baptist Medical Center South On Thursday, 18-year-old Lora Michael Troy Hutto, in Jacksonville on Grace Duncan, of a co-founder of faces manslaughter, Friday in connection Lake City, was found the Salt Life brand weapons charges. to a murder investiga- deceased in the Singer that now lives in tion in Riviera Beach. Island Hilton during a Wellborn, was Staff report In addition the well-being check by arrested Friday in JACKSONVILLE — The co-found- manslaughter charge, authorities, according Jacksonville by the er of the Salt Life brand has been Hutto also faces a to the Riviera Beach Florida Highway charged with manslaughter in the charge possession of Police Department Patrol in connection Hutto Duncan death of a Lake City teen. a firearm —both on and Columbia County to the death of a Michael Troy Hutto, a 54-year-old warrants from Riviera Beach — accord- Sheriff’s Office. Columbia County multi-millionaire who now lives in ing to the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office teen. Wellborn, was arrested by state troop- Department of Corrections. DEATH continued on 2A COURTESY FHP JACKSONVILLE LCPD: Let the fun begin! Lobby at tax office It’s safe opening to live up again Starting Monday, here patrons can avoid car drive-through line. -

Printmgr File

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2008 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 001-32686 VIACOM INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) DELAWARE 20-3515052 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification Number) 1515 Broadway New York, NY 10036 (212) 258-6000 (Address, including zip code, and telephone number, including area code, of registrant’s principal executive offices) Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange on Title of Each Class Which Registered Class A Common Stock, $0.001 par value New York Stock Exchange Class B Common Stock, $0.001 par value New York Stock Exchange 6.85% Senior Notes due 2055 New York Stock Exchange Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title Of Class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes È No ‘ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ‘ No È Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Written Statement of Ms. Cyma Zarghami President of Nickelodeon and the MTV Networks Kids & Family Group

Written Statement of Ms. Cyma Zarghami President of Nickelodeon and the MTV Networks Kids & Family Group Before the Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation of the United States Senate ―Rethinking the Children's Television Act for a Digital Media Age‖ July 22, 2009 Thank you, Chairman Rockefeller and Ranking Member Hutchison for inviting me to be a part of today‘s hearing. My name is Cyma Zarghami, and I am President of Nickelodeon and the MTV Networks Kids & Family Group. I am proud to say that I have been with Nickelodeon for 24 years, beginning as a data entry clerk, and now work on a wide range of programs including Dora The Explorer, SpongeBob SquarePants, Rugrats and Bill Cosby‘s Little Bill. I‘ve also worked on our pro-social initiatives, such as our Kids Pick the President Campaign. During my time at Nickelodeon, I have watched the American family change and our networks grow in amazing and important ways. So I am excited to share our story with the Committee this afternoon. Nickelodeon‘s Kids and Family Group is comprised of four television networks: the flagship Nickelodeon channel; Noggin, The N, and Nicktoons.1 The Group also includes online, digital, consumer products and recreation businesses focused on children and families. 1 Nickelodeon has announced plans to rename Noggin as Nick Jr. and The N as TeenNick on September 28, 2009. 1 Nickelodeon was launched 30 years ago and it has been the #1 rated cable network for the past 15 years, reaching over 98 million American households. It is the most widely distributed channel in the world and can be viewed in over 175 countries.