The Chaldon Labyrinths Jeff Saward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Offices, 8 Station Road East, Oxted, Surrey RH8 0BT [email protected] Tel: 01883 722000, Dx: 39359 OXTED

Council Offices, 8 Station Road East, Oxted, Surrey RH8 0BT [email protected] Tel: 01883 722000, Dx: 39359 OXTED If calling please ask for Paige Barlow On 01883 732861 Mr Jeremy Stillman 95-97 High Street, E-mail: [email protected] St Mary Cray Orpington Our ref: 2019/1983/NC BR5 3NH Your ref: Date: 31st January 2020 On behalf of Mr. Suresh Patel TOWN AND COUNTY PLANNING (GENERAL PERMITTED DEVELOPMENT) (AMENDMENT) (ENGLAND) ORDER. SCHEDULE 2, PART 3, CLASS M, OF THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (GENERAL PERMITTED DEVELOPMENT) (ENGLAND) ORDER 2015 (as amended) Application No. : TA/2019/1983/NC Site : 100 Chaldon Road, Caterham CR3 5PH Proposal : Part change of use of ground from Class A1 use (Retail) to Class C3 use (Residential) to form 1 x 1-bedroom self-contained flat (Prior Notification). I am writing further to the above Notification for a change of use from Class A1(Retail) to Class C3 (dwellinghouses) registered on 12th November 2019. Tandridge District Council, as local planning authority, hereby confirms that PRIOR APPROVAL IS REQUIRED AND IS GIVEN for the proposed development at the above address as described and in accordance with the information that the developer has provided to the local planning authority. INFORMATIVES 1. This written notice confirms that the proposed development would comply with the provisions of Schedule 2, Part 3, Class M of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order (England) 2015 (as amended). 2. The development shall be carried out in accordance with the application details provided to the District Planning Authority by the applicant and scanned on 12th November 2019. -

Chaldon Walks Chaldon Residents Walked Each of Its Footpaths Regularly Twice a Year from the 1920S Until a Few Years Ago

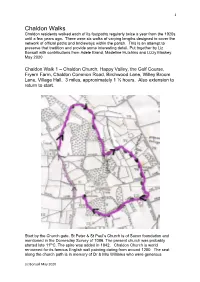

1 Chaldon Walks Chaldon residents walked each of its footpaths regularly twice a year from the 1920s until a few years ago. There were six walks of varying lengths designed to cover the network of official paths and bridleways within the parish. This is an attempt to preserve that tradition and provide some interesting detail. Put together by Liz Bonsall with contributions from Adele Brand, Madeline Hutchins and Lizzy Maskey. May 2020 Chaldon Walk 1 – Chaldon Church, Happy Valley, the Golf Course, Fryern Farm, Chaldon Common Road, Birchwood Lane, Willey Broom Lane, Village Hall. 3 miles, approximately 1 ½ hours. Also extension to return to start. Start by the Church gate. St Peter & St Paul’s Church is of Saxon foundation and mentioned in the Domesday Survey of 1086. The present church was probably started late 11thC. The spire was added in 1842. Chaldon Church is world renowned for its famous English wall painting dating from around 1200. The seat along the church path is in memory of Dr & Mrs Williams who were generous Liz Bonsall May 2020 2 benefactors. Notice the new lamp posts to your left, installed in early 2020 to light the path. There are ancient yew trees in the churchyard and three of the large tombs near the shed have Listed Building status (Grade II). The church itself is a Grade I Listed Building. From the gate you can glimpse 14thC Chaldon Court (Grade II*) through the trees to your left. From the gate walk down the lane keeping the graveyard on your left. On your right is the triangle of Church Green, named as common land on maps from 1825 and 1837. -

Tandridge District IDP July Publication

Our Local Plan Tandridge District Infrastructure Delivery Plan July 2018 Contents What this document does and does not do 1. Introduction Purpose of the Infrastructure Delivery Plan Structure of the Infrastructure Delivery Plan 2. Definition of Infrastructure 3. Infrastructure Planning Context National Planning Policy Framework Planning Practice Guidance Local Plan (2013 - 2033) Area Action Plans Neighbourhood Plans 4. Infrastructure Funding Mechanisms Community Infrastructure Levy Section 106 Planning Agreements Section 278 Highway Agreements Planning Conditions Other Funding Sources 5. Cross - boundary Infrastructure Needs 6. Summary of Key Infrastructure Requirements 7. Infrastructure Costs Appendix A - Strategic Infrastructure Transport Education Health Recreation, Sports and Community Facilities Utilities/Broadband Flood Defence Green Infrastructure Appendix B - Cross-boundary Infrastructure Needs 1 Tandridge District Infrastructure Delivery Plan WhatIncludes does detail this of itsdocument strategy to deliver do? WhatDoes this not allocatedocument land for does development, not Affordable Housing and Gypsy and this can only be done through the Local Traveller provision. do?Plan. Describes the evidence base used to Setsinform out the the determination known infrastructure of the Spatial It does not limit the infrastructure that needsStrategy of andthe district,its housing and targetidentifies may be sought in order to support where improvements are required development coming forward as part of the Local Plan Is an evidence base paper to the Local Does not influence, establish or impact Plan upon the Local Plan Spatial Strategy or its principles Is a live document that will be updated as and when more information is obtained 2 Tandridge District Infrastructure Delivery Plan 1. Introduction The provision of infrastructure in the right location at the right time is important for our communities and the district as a whole. -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Tandridge in Surrey

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE FUTURE ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR TANDRIDGE IN SURREY Report to the Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions September 1998 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND This report sets out the Commission’s final recommendations on the electoral arrangements for Tandridge in Surrey. Members of the Commission are: Professor Malcolm Grant (Chairman) Helena Shovelton (Deputy Chairman) Peter Brokenshire Professor Michael Clarke Pamela Gordon Robin Gray Robert Hughes Barbara Stephens (Chief Executive) ©Crown Copyright 1998 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Local Government Commission for England with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. ii LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CONTENTS page LETTER TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE v SUMMARY vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 CURRENT ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS 3 3 DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS 7 4 RESPONSES TO CONSULTATION 9 5 ANALYSIS AND FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS 11 6 NEXT STEPS 21 APPENDICES A Final Recommendations for Tandridge: Detailed Mapping 23 B Draft Recommendations for Tandridge (March 1998) 29 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND iii iv LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND Local Government Commission for England September 1998 Dear Secretary of State On 2 September 1997 the Commission began a periodic electoral review of the district of Tandridge under the Local Government Act 1992. -

Your Handbook to Life in Caterham on the Hill & Surrounding Areas

The Guide Your handbook to life in Caterham on the Hill & surrounding areas Discover your local area Beyond the boundaries of Oakgrove, an equally enviable lifestyle awaits. Surrounded by beautiful Surrey countryside, one of the best golf courses within the M25 on your doorstep and both Caterham on the Hill and Caterham town centres within walking distance. A wide range of schools for children of all ages, essential shops, services and excellent amenities are all available, along with easy access to Central London, Gatwick and the South Coast. The following pages set out local amenities and places you may find useful if you are new to the area. Map not to scale 01 CONTENTS 3-6: DINING OUT Caterham and the surrounding towns and villages offer a wide range of independent restaurants, as well as the more popular chains. Whether it’s Italian, French or Asian cuisine you are looking for you’ll never be more than 20 minutes away at Oakgrove. 7-8: RETAIL THERAPY If you’re looking for famous High Street stores or independent & ESSENTIALS boutiques they are all within easy reach. Caterham’s Church Walk Shopping Centre has all the essentials you need whilst a short drive away, Croydon boasts a larger retail centre for all your major shopping needs. 9-10: ENTERTAINMENT Whether you are looking to keep the kids entertained by taking a trip to nearby Godstone Farm, prefer to play a round of golf or simply relax watching a film on the silver screen, Caterham and the surrounding area has all the entertainment options. -

“He Hath Mingled with the Ungodly”

―HE HATH MINGLED WITH THE UNGODLY‖: THE LIFE OF SIMEON SOLOMON AFTER 1873, WITH A SURVEY OF THE EXTANT WORKS CAROLYN CONROY TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I PH.D. THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART DECEMBER 2009 2 ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on the life and work of the marginalized British Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic homosexual Jewish painter Simeon Solomon (1840-1905) after 1873.This year was fundamental in the artist‘s professional and personal life, because it is the year that he was arrested for attempted sodomy charges in London. The popular view that has been disseminated by the early historiography of Solomon, since before and after his death in 1905, has been to claim that, after this date, the artist led a life that was worthless, both personally and artistically. It has also asserted that this situation was self-inflicted, and that, despite the consistent efforts of his family and friends to return him to the conventions of Victorian middle-class life, he resisted, and that, this resistant was evidence of his ‗deviancy‘. Indeed, for over sixty years, the overall effect of this early historiography has been to defame the character of Solomon and reduce his importance within the Aesthetic movement and the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism. It has also had the effect of relegating the work that he produced after 1873 to either virtual obscurity or critical censure. In fact, it is only recently that a revival of interest in the artist has gained momentum, although the latter part of his life from 1873 has still remained under- researched and unrecorded. -

Chaldon Walks Chaldon Residents Walk All Their Footpaths Regularly Twice a Year and Have Done So Most Years Since the 1920S

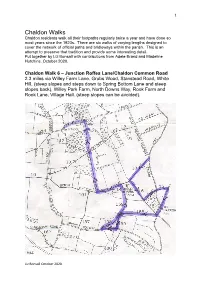

1 Chaldon Walks Chaldon residents walk all their footpaths regularly twice a year and have done so most years since the 1920s. There are six walks of varying lengths designed to cover the network of official paths and bridleways within the parish. This is an attempt to preserve that tradition and provide some interesting detail. Put together by Liz Bonsall with contributions from Adele Brand and Madeline Hutchins. October 2020. Chaldon Walk 6 – Junction Roffes Lane/Chaldon Common Road 2.3 miles via Willey Farm Lane, Grubs Wood, Stanstead Road, White Hill, (steep slopes and steps down to Spring Bottom Lane and steep slopes back), Willey Park Farm, North Downs Way, Rook Farm and Rook Lane, Village Hall. (steep slopes can be avoided). Liz Bonsall October 2020 2 This walk starts at the junction of Chaldon Common Road with Roffes Lane. Walk up Willey Farm Lane, a rough concrete track. At the end of the row of houses there are open fields to the right. In 1970 these were proposed as a new site for Eothen School but turned down on the grounds of inaccessibility. At the junction, before you follow the track to your left, see the information board there at the top of the hill, provided by Chaldon Village Council in 2017. At this point on a clear day you can see the London skyline. With your back to the board, Willey Park Farm house can be glimpsed from here, and looking towards it, on the right hand side of the track, in the trees, is the site of one of Willey Farm’s ancient ponds. -

357 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

357 bus time schedule & line map 357 Selsdon - Reigate View In Website Mode The 357 bus line (Selsdon - Reigate) has 7 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chelsham: 7:18 AM - 6:18 PM (2) Oxted: 7:18 AM (3) Redhill: 6:48 PM (4) Reigate: 6:43 AM - 5:18 PM (5) Selsdon/South Croydon: 8:18 AM - 4:18 PM (6) Warlingham: 3:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 357 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 357 bus arriving. Direction: Chelsham 357 bus Time Schedule 72 stops Chelsham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Bell Street, Reigate 12 Bell Street, England Tuesday Not Operational High Street, Reigate Wednesday Not Operational High Street, England Thursday Not Operational Red Cross, Reigate Friday 7:18 AM - 6:18 PM London Road, England Saturday Not Operational Reigate Sixth Form College, Reigate The Roe Deer, Reigate Heath 39 - Flats 1-10 Croydon Road, England 357 bus Info Lorian Drive, Reigate Heath Direction: Chelsham Stops: 72 Wray Common, Reigate Trip Duration: 68 min Wray Lane, England Line Summary: Bell Street, Reigate, High Street, Reigate, Red Cross, Reigate, Reigate Sixth Form Batts Hill, Wray Common College, Reigate, The Roe Deer, Reigate Heath, Lorian 15 Batts Hill, England Drive, Reigate Heath, Wray Common, Reigate, Batts Hill, Wray Common, Colebrooke Road, Redhill, Colebrooke Road, Redhill Timperley Gardens, Redhill, Park Road, Redhill, 21 Green Lane, England Regent Crescent, Redhill, The Frenches, Redhill, Ladbroke Road, Redhill, Redhill Bus -

Tandridge Photographic Society

Tandridge Photographic Society COMPETITION: Alec Braid Trophy (Colour Print) JUDGE: Tony Charters DATE: 27/02/2014 # Author Title Score WINNER 1 Clare Pickett Tandridge district council recycling Tandridge district council recycling not the prettiest of places, but key to improving our environment. 2 Brian Smith Reflections in a Golden Pond Sunset reflections on Surrey National Golf Course, and Bay Ponds. 3 Dominic Murtagh Winter, Spring and Summer in Tandridge From hoar frost to water lilies to roses in bloom. Even Monet might have fancied a spring visit to Tandridge. 4 Peter O'Hare Colours of Tandridge The Panel aims to show the seasons and colours of rural Tandrige Landscapes. All images are local to the club: Godstone, Staffhurst Wood and Limpsfield Chart. You dont have to go far for inspiration 5 Alan Gristwood Leisure time around Tandridge Runner-Up 6 David Hurkett St George's church and Yew tree, Crowhurst WINNER Page 1 of 3 Tandridge Photographic Society COMPETITION: Alec Braid Silver Medal (Mono Print) JUDGE: Tony Charters DATE: 27/02/2014 # Author Title Score WINNER 1 Clare Pickett Tandridge Photographic Society WINNER Tandridge photographic society celebrates it's 50years. This Kodak Retinette 1B is a camera a member might possibly have used then. Page 2 of 3 Tandridge Photographic Society COMPETITION: Alec Braid Bronze Medal (PDI) JUDGE: Tony Charters DATE: 27/02/2014 # Author Title Score WINNER 1 Michel Gosset A dog's life in Tandridge Winter on Greensand Way , Spring in the bluebells at Stafford Wood, Summer over river Eden at Stockett's Manor 2 Brian Smith Residents of Park Ham WINNER Park Ham is an SSSI on the border of Chaldon, and this chalk downland habitat is maintained by willing flocks of Herdwick, Jacobs amd Beulah sheep. -

St Peter & St Paul, Chaldon

St Peter & St Paul, Chaldon READERS’ ROTA www.chaldonchurch.co.uk th Oct. 4 Ann Howard 1 Timothy 6 vv 6 – 10 th Harvest Pat Johnson Matthew 6 vv 25 - 33 4 October 2015 Festival Oct. 11th Peter Taylor Amos 5 vv 6 – 7 , 10 – 15 CHURCH NOTICES Trinity 19 Angela Charlton Hebrews 4 vv 12 – end Lorraine Elliott Mark 10 vv 17 - 31 Welcome to all visitors. Oct. 18th June Milliams Acts 16 vv 6 – 12a St. Luke Charlotte Tracy 2 Timothy 4 vv 5 – 17 PLEASE PRAY FOR Sarah Hayhurst Luke 10 vv 1 – 9 th 1. Christopher, Bishop of Southwark and Jonathan, Oct. 25 Mark Oswald Jeremiah 31 vv 7 – 9 Bishop of Croydon. Last after Alison Forster Hebrews 7 vv 23 – end Trinity John Gilbert Mark 10 vv 46 – end 2.The Caterham Team Ministry and all it’s clergy. st 3. Our Zimbabwe Link Parish, St Matthew’s, Gweru Nov. 1 Wisdom 3, vv1-9 4. The sick: Ron Hockaday; Pat and Pete Adkins; Jane All Saints Molly Hayhurst Revelation 21, vv1-6a Callum Cooke John 11, vv32-44 Gostling; John Amos; Felicity Gill; Julia, Pam and Nov. 8th Alan Simon Jonah 3, vv1-5,10 Peter Campbell; Robert & Sally Vincent. Also for Remembran Gloria Loyd Hebrews 9, vv24-end those who care for them, and the bereaved. ce Sunday Mary Richards Mark 1, vv14-20 5. The departed: John Neale Nov. 15th Janet Simon Daniel 12 ,vv1-3 2nd before Elizabeth Hewlett Hebrews 10, vv11-25 CALENDAR OF SERVICES Advent Pat Johnson Mark 13, vv1-8 nd 4th October HARVEST FESTIVAL Nov. -

Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Development Plan Referendum

CATERHAM, CHALDON AND WHYTELEAFE NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN REFERENDUM INFORMATION FOR VOTERS About this booklet On Thursday 6 May 2021, there will be a referendum on a neighbourhood plan for your area. This booklet explains more about the referendum that is going to take place and how you can take part in it. In this booklet you can find out about: • The referendum and how you can take part • The neighbourhood area • The neighbourhood plan • The development plan (of which neighbourhood plans are part) Referendum on the Neighbourhood Plan A referendum asks you to vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to a question. The question which will be asked in the Referendum is: “Do you want Tandridge District Council to use the neighbourhood plan for Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe to help it decide planning applications in the neighbourhood area?” How do I vote in the referendum? You vote by putting a cross (X) in the ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ box on your ballot paper. Put a cross in only one box or your vote will not be counted. If more people vote ‘yes’ than ‘no’ in this referendum, the Neighbourhood Development Plan will become part of the District’s statutory development plan. Tandridge District Council will then use the Neighbourhood Plan to help it decide planning applications in the parishes of Caterham-on-the-Hill, Caterham Valley, Chaldon and Whyteleafe. If more people vote ‘no’ than ‘yes’, then planning applications will be decided without using the Neighbourhood Development Plan for the local area. What is Neighbourhood Planning? The Localism Act 2012 and subsequent Neighbourhood Planning Regulations allow communities to guide and shape development in their locality by undertaking neighbourhood planning. -

Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan

Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan Design Guidelines FINAL REPORT November 2018 Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan Quality information Project role Name Position Action summary Signature Date Qualifying body Various Caterham, Chaldon Review 19.07.2018 and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan Director / QA Ben Castell Technical Director 30.08.2018 Researcher Luis Juarez Urban and Landscape Research, site 30.08.2018 Design visit, drawings Simon Jenkins Graziano Di Gregorio Project Coordinator Mary Kucharska Project Coordinator Review 22.10.2018 This document has been prepared by AECOM Limited (“AECOM”) in accordance with its contract with Locality (the “Client”) and in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. AECOM shall have no liability to any third party that makes use of or relies upon this document. © 2018 AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited. 2 AECOM Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 1.1. About this document ......................................................................................................................................................................................