The Efficacy of Business Continuity Planning: Stories from a Natural Disaster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network List Addendum

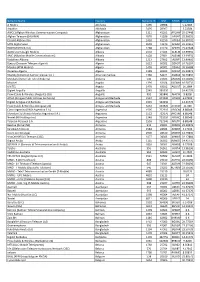

Network List Addendum IN-SITU PROVIDED SIM CELLULAR NETWORK COVERAGE COUNTRY NETWORK 2G 3G LTE-M NB-IOT COUNTRY NETWORK 2G 3G LTE-M NB-IOT (VULINK, (TUBE, (VULINK) (VULINK) TUBE, WEBCOMM) (VULINK, (TUBE, (VULINK) (VULINK) WEBCOMM) TUBE, WEBCOMM) WEBCOMM) Benin Moov X X Afghanistan TDCA (Roshan) X X Bermuda ONE X X Afghanistan MTN X X Bolivia Viva X X Afghanistan Etisalat X X Bolivia Tigo X X Albania Vodafone X X X Bonaire / Sint Eustatius / Saba Albania Eagle Mobile X X / Curacao / Saint Digicel X X Algeria ATM Mobilis X X X Martin (French part) Algeria Ooredoo X X Bonaire / Sint Mobiland Andorra X X Eustatius / Saba (Andorra) / Curacao / Saint TelCell SX X Angola Unitel X X Martin (French part) Anguilla FLOW X X Bosnia and BH Mobile X X Anguilla Digicel X Herzegovina Antigua and Bosnia and FLOW X X HT-ERONET X X Barbuda Herzegovina Antigua and Bosnia and Digicel X mtel X Barbuda Herzegovina Argentina Claro X X Botswana MTN X X Argentina Personal X X Botswana Orange X X Argentina Movistar X X Brazil TIM X X Armenia Beeline X X Brazil Vivo X X X X Armenia Ucom X X Brazil Claro X X X Aruba Digicel X X British Virgin FLOW X X Islands Australia Optus X CCT - Carribean Australia Telstra X X British Virgin Cellular X X Islands Australia Vodafone X X Telephone Austria A1 X X Brunei UNN X X Darussalam Austria T-Mobile X X X Bulgaria A1 X X X X Austria H3G X X Bulgaria Telenor X X Azerbaijan Azercell X X Bulgaria Vivacom X X Azerbaijan Bakcell X X Burkina Faso Orange X X Bahamas BTC X X Burundi Smart Mobile X X Bahamas Aliv X Cabo Verde CVMOVEL -

2020-07-14 MASTERFILE Iots and More Whereever

Network Coverage Q3 2020 Country Network Afghanistan Etisalat MTN TDCA (Roshan) Albania Albanian Mobile Communications Eagle Mobile Vodafone Algeria ATM Mobilis Ooredoo Andorra Mobiland (Andorra) Anguilla Digicel FLOW Antigua and Barbuda Digicel FLOW Argentina Claro Movistar Armenia Beeline Ucom Aruba Digicel Australia Optus Telstra Vodafone Austria A1 H3G T-Mobile Azerbaijan Azercell Bakcell Bahamas Aliv BTC Bahrain Batelco MTC Vodafone (Zain) Bangladesh Banglalink Grameenphone Barbados Digicel FLOW Belarus MTS velcom Belgium Base Orange Proximus Belize DigiCell Benin Moov Bermuda Digicel ONE Bolivia Tigo Viva Bonaire / Sint Eustatius / Saba / Curacao / Saint MartinDigicel (French part) 1 Network Coverage Q3 2020 Country Network Telcell NV Bosnia and Herzegovina BH Mobile HT-ERONET mtel Brazil Claro TIM Vivo British Virgin Islands CCT - Carribean Cellular Telephone FLOW Brunei Darussalam B-Mobile (Progresif) DSTCom Bulgaria A1 Telenor Vivacom Burkina Faso Orange Burundi Smart Mobile Cambodia CamGSM Metfone (Viettel) Smart Cameroon MTN Canada Bell Rogers Wireless SaskTel TELUS Videotron Cape Verde CVMOVEL Unitel (T+) Cayman Islands Digicel FLOW Chad Airtel Chile Claro Entel Movistar WOM S.A. China China Mobile China Telecom China Unicom Colombia Claro Movistar Costa Rica Claro ICE Movistar Cote d'Ivoire MTN Croatia A1 T-Mobile Tele2 2 Network Coverage Q3 2020 Country Network Cyprus CYTAmobile-Vodafone MTN Primetel Czech Republic O2 T-Mobile Vodafone Democratic Republic of Congo Africell Airtel Tigo Vodacom Denmark Hi3G TDC Telenor Telia Dominica Digicel FLOW Dominican Republic Altice Claro Viva Ecuador Claro CNT Movistar Egypt Orange Vodafone El Salvador Claro Digicel Movistar Tigo Equatorial Guinea Hits Guinea Estonia Elisa Tele2 Telia Ethiopia Ethio Telecom Faroe Islands Faroese Telecom Hey Fiji / Nauru Digicel Vodafone Finland Alcom DNA Elisa Telia France Bouygues Free Mobile Orange SFR French Guiana / St Barthelemy / St. -

Mobile Network Codes (MNC) for the International Identification Plan for Public Networks and Subscriptions (According to Recommendation ITU-T E.212 (09/2016))

Annex to ITU Operational Bulletin No. 1162 – 15.XII.2018 INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION TSB TELECOMMUNICATION STANDARDIZATION BUREAU OF ITU __________________________________________________________________ Mobile Network Codes (MNC) for the international identification plan for public networks and subscriptions (According to Recommendation ITU-T E.212 (09/2016)) (POSITION ON 15 DECEMBER 2018) __________________________________________________________________ Geneva, 2018 Mobile Network Codes (MNC) for the international identification plan for public networks and subscriptions Note from TSB 1. A centralized List of Mobile Network Codes (MNC) for the international identification plan for public networks and subscriptions has been created within TSB. 2. This List of Mobile Network Codes (MNC) is published as an annex to ITU Operational Bulletin No. 1162 of 15.XII.2018. Administrations are requested to verify the information in this List and to inform ITU on any modifications that they wish to make. The notification form can be found on the ITU website at http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-T/inr/forms/Pages/mnc.aspx . 3. This List will be updated by numbered series of amendments published in the ITU Operational Bulletin. Furthermore, the information contained in this Annex is also available on the ITU website. 4. Please address any comments or suggestions concerning this List to the Director of TSB: International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Director of TSB Tel: +41 22 730 5211 Fax: +41 22 730 5853 E-mail: [email protected] 5. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this List do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ITU concerning the legal status of any country or geographical area, or of its authorities. -

Country Name Country Prefix Operator Name Afghanistan 93 Areeba Afghanistan 93 Etisalat Afghanistan 93 TDCA Afgha

Country Name Country Prefix Operator Name Afghanistan 93 Areeba Afghanistan 93 Etisalat Afghanistan 93 TDCA Afghanistan 93 TSI Albania 355 AMC Albania 355 Eagle Mobile Albania 355 Plus AL Albania 355 Vodafone Albania Algeria 213 ATM Mobilis Algeria 213 Djezzy Algeria 213 Nedjma Andorra 376 Mobiland Angola 244 Movicel Angola Angola 244 Unitel Anguilla 1 264 C&W Anguilla Anguilla 1 264 Digicel Anguilla Antigua & Barbuda 1 268 APUA PCS Antigua & Barbuda 1 268 Digicel Ant&Barbuda Argentina 54 Claro Argentina Argentina 54 Movistar Argentina Argentina 54 Nextel Argentina Argentina 54 Personal Argentina Armenia 374 ArmenTel Armenia 374 Karabakh Telecom Armenia 374 Orange Aruba 297 NeWMillenium Digicel Australia 61 Australia Optus Australia 61 Australia Telstra Australia 61 Australia Virgin Mobile Australia 61 Australia Vodafone Austria 43 Austria A1 Austria 43 Austria H3G Austria 43 Austria One Austria 43 Austria T-Mobile Azerbaijan 994 Azercell Azerbaijan 994 Azerfon (Nar Mobile) Azerbaijan 994 Bakcell Bahamas 1 242 Bahamas Telecom Bahrain 973 Batelco Bahrain 973 Viva Bahrain Bahrain 973 Zain Bahrain(MTC) Bangladesh 880 AkTel Bangladesh 880 Grameenphone Bangladesh 880 Sheba Telecom aggiornata al 17/11/2014 pag 1 di 17 Country Name Country Prefix Operator Name Afghanistan 93 Areeba Bangladesh 880 Teletalk Bangladesh 880 Warid Bangladesh Barbados 1 246 Rest** Barbados 1 246 C&W Barbados Barbados 1 246 Digicel Barbados Belarus 375 BeST Belarus 375 MTS Belarus Belarus 375 Velcom Belgium **** 32 Belgium Base Belgium **** 32 Belgium Mobistar Belgium -

LTE Subscriptions, Deployments, Spectrum And

+44 20 8123 2220 [email protected] LTE Subscriptions, Deployments, Spectrum and Infrastructure Contracts Database Q1’2012 database https://marketpublishers.com/r/L4BD65D9A10EN.html Date: January 2012 Pages: 100 Price: US$ 1,000.00 (Single User License) ID: L4BD65D9A10EN Abstracts Driven by the growing demand for mobile broadband access, LTE adoption has considerably gained momentum throughout the globe with over 49 commercial deployments. Driven by these early launches global LTE subscriptions reached 6.4 Million at the end of Q4’2011. From an operator viewpoint Verizon Wireless (U.S) is leading the market with a 64 % market share thanks to its tremendous coverage footprint that currently spans across 178 regional markets in the United States. Verizon’s market share is followed by NTT DoCoMo, which represents 23 % of all LTE subscriptions. Going forward, the LTE market is set to grow with a CAGR of 150 % over the next 5 years and will eventually represent more than 8 % of all mobile connections by 2016, with 613 Million subscriptions. By that time China Mobile will be the leading LTE operator with its TD-LTE network accounting for over 17 % of all LTE subscriptions worldwide. Covering over 810 operators, 53 infrastructure vendors and 222 countries worldwide the “LTE Subscriptions, Deployments, Spectrum and Infrastructure Contracts Database Q1’2012” tracks global cellular network deployments, infrastructure vendor contracts, and subscriptions. The report includes: List of all 2G/3G/4G Infrastructure contracts by technology, region, country, vendor and operator 2G/3G/4G Infrastructure market share by equipment type, region, country and vendor 2G/3G/4G network RF spectrum holdings by bandwidth, frequency, region, country and operator. -

Digice Digicel Aruba Aruba North America

BO Code Name Pais Continent ABW-Digice Digicel Aruba Aruba North America ABW-SETAR Servicio di Telecomunicacion di Aruba (ABWSE) Aruba North America AFG-Etisal Emirates Telecom Corp (ETISALAT) (AFGEA) Afganistán Asia AFG-TDCA Telecom Development Company Afghanistan, Corporation (TDCA) Afganistán Asia AGO-Movicel Movicel - Telecomunicações, S.A. (AGOMV) Angola Africa AGO-Unitel Unitel S.A. (AGOUT) Angola Africa ALB-AMC Telekom Albania SH.A Albania Europe ALB-Vodafone Vodafone - Albania (ALBVF) Albania Europe ALB-Plus Plus Communication sh.a (ALBM4) Albania Europe AND-STA Andorra Telecom (ANDMA) Andorra Europe ANT-Telcel Telcell N.V. (ANTTC) Antillas Hol. (Saint Maarten) North America ARE-DU Emirates Integrated Telecommunications (AREDU) Emiratos Arabes Asia ARE-Etisalat Emirates Telecom Corp-ETISALAT (ARETC) Emiratos Arabes Asia ARE-THURAY Thuraya Telecommunications Company (ARETH) Satélite Satellite Networks ARG-CTIMov AMX Argentina S.A. (ARGCM) Argentina South America ARG-Movist Telefónica Móviles Argentina S.A. (ARGTM) Argentina South America ARG-TelecomP Telecom Personal S.A. (ARGTP) Argentina South America ARM-Vivace K Telecom Closed Joint-Stock Company (ARM05) Armenia Europe ARM-Orange Ucom Limited Liability Company (ARMOR) Armenia Europe ATG-APUA Antigua Public Utilities Authority (APUA) (ATG03) Antigua y Barbuda North America AUS-Telstra Telstra Corporation Limited (AUSTA) Australia Oceania AUS-Vodafone Vodafone Hutchison Australia Pty Limited (AUSVF) Australia Oceania AUT-One Hutchison Drei Austria GmbH (AUTCA) Austria Europe AUT-TMobile T-Mobile Austria GmbH (AUTMM) Austria Europe AUT-One3G A1 Telekom Austria AG (AUTON) Austria Europe AUT-Mobilkom A1 Telekom Austria AG (AUTPT) Austria Europe AUT-Tele.rin T-Mobile Austria GmbH (AUTTR) Austria Europe AZE-Azercell Azercell Telecom LLC (AZEAC) Azerbaiyan Asia AZE-Azerfo Azerfon LLC (AZEAF) Azerbaiyan Asia AZE-Bakcell Bakcell Limited Liable Company (AZEBC) Azerbaiyan Asia BDI-Africe Africell PLC Company (BDI02) Burundi Africa BDI-Telecel U-Com Burundi S.A. -

Afghanistan Etisalat Afghanistan TDCA TSI Albania AMC Eagle

Afghanistan Etisalat Afghanistan TDCA TSI Albania AMC Eagle Mobile Vodafone Albania Algeria ATM Mobilis Djezzy Nedjma American Samoa AmericaSamoa Telecom Blue Sky Comms Andorra Mobiland Angola Movicel Angola Unitel Anguilla C&W Anguilla Digicel Anguilla Antigua + Barbuda APUA PCS Digicel Ant&Barbuda Argentina Claro Movistar (Unifon) Nextel Personal Armenia ArmenTel Karabakh Telecom Orange AM Aruba NewMillenium Digicel SETAR Australia 3 Australia Optus Telstra Vodafone Pacific Austria 3 Austria Mobilkom One T-Mobile (Tele.Ring) T-Mobile Austria Azerbaijan Azercell Azerfon (Nar Mobile) Bakcell Catel Bahamas Bahamas Telecom Bahrain Batelco Viva Bahrain Zain Bahrain(MTC) Bangladesh AkTel CityCell Grameenphone Sheba Telecom Teletalk Barbados C&W Barbados Digicel Barbados Sunbeach Barbados Belarus BeST Diallog MTS Belarus Velcom Belgium Base Mobistar Proximus Belize Belize Telecom Smart BZ Benin Bell Benin BJ Glo Mobile Benin Libercom MTN Benin(Spacetel) Telecel BJ Bermuda CellularOne Bermuda Digicel Bermuda Mobility Bolivia Entel Bolivia Nuevatel Tigo Bolivia Bosnia Eronet Mobilna Srpske PTT BIH Botswana BTC Mobile Botswana Mascom OrangeBtwna(Vista) Brazil Amazonia Cellular CTBC Cellular Claro Nextel Brazil Oi Sercomtel TIM TIM (Centro Sul) TIM (Sao Paolo) TNL PCS (Oi) Vivo Vivo (Telemig) Brunei B-Mobile DST Communications Jabatan Telekom Bulgaria BTC Mobile Globul MobilTel Burkina Faso Moov Burkina Faso Telmob (Onatel) Zain Burkina Faso Burundi Econet Burundi (Spacetel) Lacell SU Safaris Telecel Burundi U-Com Burundi Cambodia CamGSM Camshin -

IN the UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT for the EASTERN DISTRICT of VIRGINIA RICHMOND DIVISION

Case 20-32299-KLP Doc 1498 Filed 02/19/21 Entered 02/19/21 18:50:04 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 145 IN the UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR the EASTERN DISTRICT of VIRGINIA RICHMOND DIVISION ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) INTELSAT S.A., et al.1 ) Case No. 20-32299 (KLP) ) Debtors. ) (Jointly Administered) ) AFFIDAVIT of SERVICE I, Victoria X. Tran, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned case. On February 12, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B: • Joint Chapter 11 Plan of Reorganization of Intelsat S.A. and its Debtor Affiliates (Docket No. 1467) • Disclosure Statement for the Joint Chapter 11 Plan of Reorganization of Intelsat S.A. and its Debtor Affiliates (Docket No. 1468) • Debtors’ Motion for Entry of an Order (I) Approving the Adequacy of the Disclosure Statement, (II) Approving the Solicitation Procedures with Respect to Confirmation of the Debtors’ Proposed Chapter 11 Plan, (III) Approving the Forms of Ballots and Notices in Connection Therewith, (IV) Scheduling Certain Dates with Respect Thereto, and (V) Granting Related Relief (Docket No. 1469) • Notice of Motions and Notice of Hearing (Docket No. 1470) Furthermore, on February 12, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following document to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit C: • Notice of Motions and Notice of Hearing (Docket No. -

Sms Coverage

SMS COVERAGE © 2013 Click SMS Ltd East House, 109 South Worple Way, London SW14 8TN Yes ++ - MNP Support (Mobile Number Portability). SMS delivery to ported mobile numbers - where the mobile number has been re-registered to an alternative local mobile network. Operator Region Country Coverage Etisalat Afghanistan Asia Pacific Afghanistan Yes TDCA Asia Pacific Afghanistan Yes TSI Asia Pacific Afghanistan Yes AMC Europe Albania Yes Eagle Mobile Europe Albania Yes Vodafone Albania Europe Albania Yes ATM Mobilis Africa Algeria Yes Djezzy Africa Algeria Yes Nedjma Africa Algeria Yes Mobiland Europe Andorra Yes Movicel Angola Africa Angola Yes Unitel Africa Angola Yes C&W Anguilla Latin America Anguilla Yes Digicel Anguilla Latin America Anguilla Yes APUA PCS Latin America Antigua + Barbuda Yes CTI Movil Latin America Argentina Yes Nextel Argentina Latin America Argentina Yes Telecom Personal Latin America Argentina Yes Movistar (Unifon) Latin America Argentina Yes ArmenTel Europe Armenia Yes Karabakh Telecom Europe Armenia Yes NewMillenium Digicel Latin America Aruba Yes SETAR Latin America Aruba Yes 3 Australia Asia Pacific Australia Yes ++ Optus Asia Pacific Australia Yes ++ Telstra Asia Pacific Australia Yes ++ Vodafone Pacific Asia Pacific Australia Yes ++ 3 Austria Europe Austria Yes ++ Mobilkom Europe Austria Yes ++ One Europe Austria Yes ++ T-Mobile (Tele.Ring) Europe Austria Yes ++ T-Mobile Austria Europe Austria Yes ++ Azercell Europe Azerbaijan Yes Azerfon (Nar Mobile) Europe Azerbaijan Yes Bakcell Europe Azerbaijan Yes Batelco -

Pricing-Sms Outbound Global

Network Name Country Network ID NNC TADIG your cost A-Mobile Abkhazia 3196 28988 5.22384 Aquafon Abkhazia 3195 28967 5.22384 AWCC (Afghan Wireless Communication Company) Afghanistan 1311 41201 AFGAW 25.07448 Afghan Telecom (SALAAM) Afghanistan 4570 41288 AFGAT 29.56692 Etisalat Afghanistan Afghanistan 2410 41250 AFGEA 16.50732 MTN Afghanistan Afghanistan 2648 41240 AFGAR 33.11916 ROSHAN (TDCA Ltd) Afghanistan 1268 41220 AFGTD 25.07448 ALBtelecom (Eagle Mobile) Albania 2450 27603 ALBEM 13.99992 AMC (Albanian Mobile Communications) Albania 1428 27601 ALBAM 13.99992 Vodafone Albania Albania 1213 27602 ALBVF 13.99992 Djezzy (Orascom Telecom Algerie) Algeria 1612 60302 DZAOT 24.76104 Mobilis (ATM Mobilis) Algeria 1403 60301 DZAA1 36.56688 Ooredoo Algeria Algeria 1189 60303 DZAWT 35.20872 BlueSky (American Samoa License, Inc.) American Samoa 1366 54411 ASMAS 30.29832 Mobiland (Servei de Tele d'Andorra) Andorra 540 21303 ANDMA 13.58196 Movicel Angola 1396 63104 AGOMV 16.50732 UNITEL Angola 1476 63102 AGOUT 16.2984 Digicel Anguilla Anguilla 2345 365930 14.41776 Flow (Cable & Wireless (Anguilla) Ltd) Anguilla 991 365840 AIACW 9.8208 APUA (Antigua Public Utilities Authority) Antigua and Barbuda 1524 344030 ATG03 6.37308 Digicel Antigua and Barbuda Antigua and Barbuda 1929 344930 14.41776 Flow (Cable & Wireless (Antigua) Ltd) Antigua and Barbuda 3233 344920 ATGCW 11.388 Claro Argentina (AMX Argentina S.A.) Argentina 1505 722310 ARGCM 8.88048 Movistar (Telefonica Moviles Argentina S.A.) Argentina 1522 722070 ARGTM 8.88048 Nextel (NII Holdings Inc) Argentina 1348 722020 ARGNC 8.88048 Telecom Personal S.A. Argentina 1556 722340 ARGTP 8.88048 Beeline (ArmenTel) Armenia 542 28301 ARM01 28.20876 Karabakh Telecom Armenia 1584 28304 ARMKT 5.17164 Ucom LLC (Orange) Armenia 2905 28310 ARMOR 12.79836 VivaCell-MTS (K Telecom CJSC) Armenia 1077 28305 ARM05 32.17884 Digicel Aruba Aruba 1135 36302 ABWDC 14.41776 SETAR N.V.