Master's Degree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home Home Away Away 24 Erzincanspor Celta Vigo

20 / 09 / 2017 17:00 Home Asian Handicap Over/Under Home Asian Handicap Over/Under Kick-off Kick-off Matches Standing Win/Draw/Win Matches Standing Win/Draw/Win time Over/ time Over/ Handicap Odds Total Handicap Odds Total Away Under Away Under -- 24 Erzincanspor -- -- -- -- -- Home 17 Celta Vigo -0.5 1.76 Over2.5 1.83 1.75 Home 21 / 09 22 / 09 TURC -- Eskisehirspor -- -- -- -- -- Away SPN1 14 Getafe +0.5 2.1 Under2.5 1.97 3.72 Away 18:00 03:00 1072 -- Draw 2002 (N, Mp) 3.65 Draw -- Zambia Women -- -- -- -- -- Home DII19 Zaragoza -0.5 1.92 Over2/2.5 1.97 1.9 Home 21 / 09 22 / 09 WIF -- South Africa Women -- -- -- -- -- Away SPNC DII12 Lugo +0.5 1.9 Under2/2.5 1.73 3.6 Away 19:00 03:00 1073 -- Draw 2012 3.2 Draw -- Yenisey 0/+0.5 1.88 Over2 1.92 3.08 Home 9 Levante 0/+0.5 1.86 Over2.5 1.82 2.75 Home 21 / 09 22 / 09 RUC 7 Akhmat Grozny 0/-0.5 1.88 Under2 1.78 2.15 Away SPN1 4 Real Sociedad 0/-0.5 2 Under2.5 1.98 2.2 Away 20:00 04:00 1068 2.98 Draw 2003 (N, Mp) 3.42 Draw 3 Panionios 0/-0.5 1.74 Over2/2.5 2 2.03 Home -- LDU Quito (ECU) -0.5/-1 1.9 Over2/2.5 1.87 1.7 Home 21 / 09 22 / 09 GREC 5 PAS Giannina 0/+0.5 2.02 Under2/2.5 1.7 3.28 Away SACS 11 Fluminense (BRA) +0.5/+1 1.86 Under2/2.5 1.83 4.35 Away 21:00 06:15 1069 3.03 Draw 2015 3.35 Draw -- Olimpiyets +0.5 1.79 Over2 1.92 3.67 Home 2 River Plate (ARG) -1.5/-2 1.55 Over3 1.77 1.12 Home 21 / 09 22 / 09 RUC 11 Ufa -0.5 1.97 Under2 1.78 1.95 Away SACL -- Wilstermann (BOL) +1.5/+2 2.27 Under3 1.93 13 Away 23:00 06:15 1074 2.93 Draw 2016 6.7 Draw -- Krylya Sovetov 0/+0.5 1.9 Over2/2.5 -

Historical Study on the Relation Between Ancient Chinese Cuju and Modern Football

2018 4th International Conference on Innovative Development of E-commerce and Logistics (ICIDEL 2018) Historical Study on the Relation between Ancient Chinese Cuju and Modern Football Xiaoxue Liu1, Yanfen Zhang2, and Xuezhi Ma3 1Department of Physical Education, China University of Geosciences, Xueyuan Road, Haidian District, Beijing, P. R. China 2Department of Life Sciences; Xinxiang University, Xinxiang Henan Province, Eastern Section of Hua Lan Road, Hongqi District, Xinxiang City, Henan, China 3Beijing Sport University Wushu School, Information Road, Haidian District, Beijing, China [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: Ancient Chinese Cuju, Modern Football, Relationship, Development, The Same Origin Abstract: This paper studies on the origin and development of Chinese Cuju through document retrieval. Born in the period of Dongyi civilization, Chinese Cuju began to take shape during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Period, and gradually flourished during the Qin, Han, Tang and Song dynasties. Through the economic and cultural exchange between China and the West in the past ages, Cuju was introduced into Europe when Mongol expedited westward in Yuan Dynasty. Finally, it has become the modern football, which originated from ancient Chinese Cuju and developed from European competition rules and now is widely accepted and popular in the world. 1. The Cultural Background of the Study On July 15th, 2004, Mr. Blatter, the president of FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association) officially announced in the 3rd session of Soccerex Fair, that football originated in Zibo, the capital of Qi State during the Spring and Autumn Period of ancient China. Cuju (ancient football game) began in China, while modern football (eleven -player game) originated in England. -

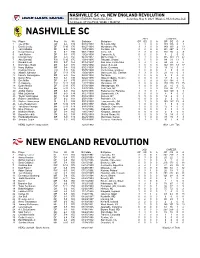

MLS Game Guide

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

China the New Continent of Football: Economic, Financial and Social

International Journal of Physical Education, Sports and Health 2018; 5(1): 65-70 P-ISSN: 2394-1685 E-ISSN: 2394-1693 Impact Factor (ISRA): 5.38 China the new continent of football: Economic, IJPESH 2018; 5(1): 65-70 financial and social evolution © 2018 IJPESH www.kheljournal.com Received: 12-11-2017 Accepted: 13-12-2017 Riccardo Izzo and Enea Belpassi Riccardo Izzo Abstract School of Healt and sport In the last few years China is becoming a well-established reality both at the Asian and European level, Science, University of Urbino The incredible rise of GDP in the last decade seems to have settled, in the last period, called of a new Carlo Bo, Italy normality, China is looking for its place in the World. To the will of the Republic, and In full agreement Enea Belpassi with his highest exponent, Secretary Xi Jinping, China decides to invest on Football, using the sport for School of Healt and sport excellence for raising awareness of their own greatness in the world. The investments made can be Science, University of Urbino basically divided into two main sectors: the import of foreign players coming above all from Europe and Carlo Bo, Italy the export of companies with great economic power for the purchase of majority and minority packages in the biggest European teams, in order to enter, even through this sport, in the European economy and business. Secondly, at least so far, investment in infrastructure and youth sectors. Keywords: Economic, financial, social evolution Introduction This work particularly focuses on the introduction of the topic, giving emphasis to the economic strenght of this new world power that is China, for investigating then thoroughly the matter of Chinese investment in the transfer for the players' sale and the purchase of European teams. -

Semantic Matching for Sequence-To-Sequence Learning

Semantic Matching for Sequence-to-Sequence Learning Ruiyi Zhang3, Changyou Cheny, Xinyuan Zhangz, Ke Bai3, Lawrence Carin3 3Duke University, yState University of New York at Buffalo, zASAPP Inc. [email protected] Abstract that each piece of mass in the source distribution is transported to an equal-weight piece of mass in the In sequence-to-sequence models, classical op- target distribution. However, this requirement is timal transport (OT) can be applied to seman- too restrictive for Seq2Seq models, making direct tically match generated sentences with target sentences. However, in non-parallel settings, applications inappropriate due to the following: (i) target sentences are usually unavailable. To texts often have different lengths, and not every tackle this issue without losing the benefits of element in the source text corresponds an element classical OT, we present a semantic matching in the target text. A good example is style transfer, scheme based on the Optimal Partial Trans- where some words in the source text do not have port (OPT). Specifically, our approach par- corresponding words in the target text. (ii) it is tially matches semantically meaningful words reasonable to semantically match important words between source and partial target sequences. e.g. To overcome the difficulty of detecting active while neglecting some other words, , conjunc- regions in OPT (corresponding to the words tion. In typical unsupervised models, text data are needed to be matched), we further exploit prior usually non-parallel in the sense that pairwise data knowledge to perform partial matching. Ex- are typically unavailable (Sutskever et al., 2014). tensive experiments are conducted to evaluate Thus, both pairwise information inference and text the proposed approach, showing consistent im- generation must be performed in the same model provements over sequence-to-sequence tasks. -

Incentives in China's Reformation of the Sports Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Keck Graduate Institute Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2017 Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry Yu Fu Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Fu, Yu, "Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry" (2017). CMC Senior Theses. 1609. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1609 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry Submitted to Professor Minxin Pei by Yu Fu for Senior Thesis Spring 2017 April 24, 2017 2 Abstract Since the 2010s, China’s sports industry has undergone comprehensive reforms. This paper attempts to understand this change of direction from the central state’s perspective. By examining the dynamics of the basketball and soccer markets, it discovers that while the deregulation of basketball is a result of persistent bottom-up effort from the private sector, the recentralization of soccer is a state-led policy change. Notwithstanding the different nature and routes between these reforms, in both sectors, the state’s aim is to restore and strengthen its legitimacy within the society. Amidst China’s economic stagnation, the regime hopes to identify sectors that can drive sustainable growth, and to make adjustments to its bureaucracy as a way to respond to the society’s mounting demand for political modernization. -

Three Trophies to Conquer

Number 100 08/2010 Three trophies to conquer UEFADirect100E.indd 1 11.08.10 16:45 2 In this issue From the World Cup to EURO 2012 4 From Offi cial Bulletin UEFA Champions League payouts 6 UEFA Europa League gets off to to UEFA·direct a promising start 8 France win European U19 Championship 10 n March 1956, a little less than two years after UEFA Spain win European Women’s U17 Iwas founded, vice-president Gustav Sebes suggested to Championship 12 the Executive Committee that a quarterly UEFA bulletin be May 1956 News from member associations 16 produced in the three UEFA offi cial languages, English, French and German, and circulated to all national member associations. His idea was accepted and, in May 1956, the maiden Cover issue of the Offi cial Bulletin came out. In his message on Under starter’s orders again, both for Europe’s the fi rst page, the UEFA president, Ebbe Schwartz, set out national teams, as the EURO 2012 quali- the publication’s aims as being to ensure “that the national fi ers get under way, and the clubs dreaming of UEFA Champions League or UEFA Europa associations of our continent may be informed of news and League glory this season. problems which occur within our continent.” Photo: UEFA-Woods From May 1956 to December 2001, 177 issues of the Offi cial Bulletin were published. During this time, the maga- zine grew in size, expanded its readership and opened up its pages to contributions from the national associations, March 1976 enabling them to share their news with their fellow UEFA members. -

Read Online for Free

2 3 Enjoy expert HR and health & safety support to get you back to business HONOURS Whether you need to manage furlough, stay COVID secure, Eccles & District League Division 2 1955-56, 1959-60 or make tough HR choices for your business, Peninsula’s here to Eccles & District League Division 3 1958-59 Manchester League Division 1 keep you safe and successful, whatever challenge you face: 1968-69 Manchester League Premier Division 1974-75, 1975-76, 1976-77, 1978-79 Northern Premier League Division 1 North • HR & Employment Law • Staff Wellbeing 2014-15 Northern Premier League Play-Off Winners 2015-16 • Health & Safety • Payroll Advice National League North 2017-18 National League Play-Off Winners 2018-19 Lancashire FA Amateur Cup 1971, 1973, 1975 Manchester FA Challenge Trophy 1975, 1976 Manchester FA Intermediate Cup 1977, 1979 All of our best wishes are with midfielder Darron Gibson for a NWCFL Challenge Cup 2006 speedy and full recovery from the injury he sustained at Port Vale. 05. Salford City vs Southend United CLUB ROLL President Dave Russell Chairman Karen Baird 5 9 Secretary Andy Giblin TAKE A STAND TAKE Kick It Out REPORTS Match Get Committee Pete Byram, Ged Carter, Barbara Gaskill, Terry Gaskill, Ian Malone, Frank McCauley, Paul Raven, George Russell, Bill Taylor, Alan Tomlinson, Dave Wilson Shop Manager Tony Sheldon Media Zarah Connolly, Ryan Deane, Will Moorcroft Photography Charlotte Tattersall, % Howard Harrison 10 Interim Head Coach Paul Scholes off any of the 17 26 VISITORS The LIONESSES Salford City GK Coach Carlo Nash Kit Manager Paul Rushton PENINSULA Physio Dave Rhodes Club Doctor Dr. -

Salford City Lionesses

2 Enjoy expert HR and health & safety support to get you back to business Whether you need to manage furlough, stay COVID secure, or make tough HR choices for your business, Peninsula’s here to keep you safe and successful, whatever challenge you face: • HR & Employment Law • Staff Wellbeing • Health & Safety • Payroll Advice Get 10 % off any of the PENINSULA services 0808 145 3388 Quote: peninsula-uk.comSalford City vs OPPONENT www.salfordcityfc.co.ukSALFORD01 3 HONOURS Eccles & District League Division 2 1955-56, 1959-60 Eccles & District League Division 3 1958-59 Manchester League Division 1 1968-69 Manchester League Premier Division 1974-75, 1975-76, 1976-77, 1978-79 Northern Premier League Division 1 North 2014-15 Northern Premier League Play-Off Winners 2015-16 National League North 2017-18 National League Play-Off Winners 2018-19 Lancashire FA Amateur Cup 1971, 1973, 1975 Manchester FA Challenge Trophy 1975, 1976 Manchester FA Intermediate Cup 1977, 1979 NWCFL Challenge Cup 2006 CLUB ROLL 11. Salford City vs Leicester City U21s President Dave Russell Chairman Karen Baird Good evening and thank you for taking the time to read through our Secretary Andy Giblin Committee Pete Byram, Ged Carter, matchday programme. Barbara Gaskill, Terry Gaskill, Ian Malone, Frank McCauley, Paul Raven, George Russell, Tonight’s edition is a shortened one due to time constraints, and we Bill Taylor, Alan Tomlinson, Dave Wilson Shop Manager Tony Sheldon have a joint edition coming up on Saturday for our back-to-back Media Zarah Connolly, Ryan Deane, Sky Bet League Two games against Cheltenham Town and Newport Will Moorcroft County which promise to be exciting clashes in the build-up to Photography Charlotte Tattersall, Howard Harrison Christmas! First Team Manager Richie Wellens GK Coach Carlo Nash A warm welcome to the visiting players and staff from Leicester; we Kit Manager Paul Rushton wish you a safe return to the Midlands afterwards and good luck for Physio Dave Rhodes the rest of your season. -

2018-2019 Year at a Glance

Month Units: Grades K-2 Units: Grades 3-5 August Rules & Warm Up Routines Rules & Warm Up Routines Locomotor Skills & Games Initiative Games Recess Games Volleyball Skills September Throwing Skills/Games Volleyball Games Parachute Activities Recess Games Drumtastic Drumtastic Juggling Skills Practice Pacer Run October Circus Stations Juggling Skills & Circus Stations Fitness Stations Fitness Testing & Stations Dancing Fun Football Skills & Games Halloween Obstacle Course Halloween Obstacle Course November Teamwork Activities Lacrosse Skills & Games African Dance with Diadie African Dance with Diadie Bowling Bowling Bowling Bowling December Fitness Stations Fitness Testing & Stations Scooter Games Basketball Skills Scooter Town Basketball Lead Up Games January Cup Stacking & Relays Table Tennis Skills & Games Fitness Stations Fitness Testing & Stations Fun Winter Games Roller Blading at GLN Jump Rope (Individual) Jump Rope (Individual) February Heart Obstacle Course Heart Obstacle Course Fitness Stations Fitness Testing & Stations Jump Rope (Group) Jump Rope (Group) Jianzi/Kickbo- Chinese New Year Jianzi/Kickbo- Chinese New Year March Ball Skills (Hands) Badminton Skills & Games Ball Skills (Feet) Soccer Skills & Games SPRING BREAK SPRING BREAK Games & Fitness Stations Games & Fitness Testing/Stations April Kickball Games Kickball/Mat Ball Games Batting Skills Archery T-Ball Games Archery Fitness Stations Fitness Testing & Stations May Spring Games Pickleball Skills & Games Fitness Stations Fitness Testing & Stations Field Day Frisbee Skills & Frisbee Golf Fun Games Fun Games. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

2011 Nerevolution Mg Sm.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLUB PAGE YOUTH DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM PAGE Welcome 2 Program Overview 198 2011 Schedule 4 Youth Program Date of Note 198 2011 Quick Facts 5 U.S. Soccer Development Academy 199 Club History 6 SUM Under-17 Cup 199 THE CLUB Gillette Stadium 8 U.S. Soccer Development Academy Clubs 200 Investor/Operators 10 Coaching Staff 201 Executives 12 Academy Alumni 202 Team Staff 14 2011 Schedules 203 Uniform History 17 Under-18 Squad 204 Under-16 Squad 206 2011 REVOLUTION PAGE 2011 Alphabetical Roster 20 MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER PAGE 2011 Numerical Roster 20 MLS Staff Directory 210 2011 Team TV/Radio Guide 21 MLS Player Rules and Regulations 211 How the Revolution Was Built 22 2010 In Review 215 Head Coach Steve Nicol 23 Chicago Fire 216 Assistant Coaches 24 Chivas USA 218 Team Staff 25 Colorado Rapids 220 Player Profiles 28 Columbus Crew 222 D.C. United 224 TEAM HISTORY PAGE FC Dallas 226 Year-by-Year Results 64 Houston Dynamo 228 2010 In Review 65 LA Galaxy 230 2009 In Review 70 New York Red Bulls 232 2008 In Review 76 Philadelphia Union 234 2007 In Review 82 Real Salt Lake 236 2006 In Review 88 San Jose Earthquakes 238 2005 In Review 94 Seattle Sounders FC 240 2004 In Review 100 Sporting Kansas City 242 2003 In Review 106 Toronto FC 244 2002 In Review 112 Portland Timbers 246 2001 In Review 119 Vancouver Whitecaps 246 2000 In Review 124 2011 Conference Alignments 247 1999 In Review 130 1998 In Review 135 MEDIA INFORMATION PAGE 1997 In Review 140 General Information & Policies 250 1996 In Review 146 Revolution Communications Directory