Geography and Public Planning: Albay and Disaster Risk Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oeconomics of the Philippine Small Pelagics Fishery

l1~~iJlLll.I.~lJ~ - r--I ~ ~~.mr'l ~ SH I 207 TR4 . #38c~.1 .I @)~~[fi]C!ffi]m @U00r@~O~~[ro)~[fi@ \ . §[fi]~~~~~~ ~~ II "'-' IDi III ~~- ~@1~ ~(;1~ ~\YL~ (b~ oeconomics of the Philippine Small Pelagics Fishery Annabelle C. ad Robert S. Pomeroy Perlita V. Corpuz Max Agiiero INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR LIVING AQUATIC RESOURCES MANAGEMENT MANILA, PHILIPPINES 407 Biqeconomics of the Philippine Small Pelagics Fishery 7?kq #38 @-,,/ JAW 3 1 1996 Printed in Manila, Philippines Published by the International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management, MCPO Box 2631, 0718 Makati, Metro Manila, Philippines Citation: Trinidad, A.C., R.S. Pomeroy, P.V. Corpuz and M. Aguero. 1993. Bioeconomics of the Philippine small pelagics fishery. ICLARM Tech. Rep. 38, 74 p. ISSN 01 15-5547 ISBN 971-8709-38-X Cover: Municipal ringnet in operation. Artwork by O.F. Espiritu, Jr. ICLARM Contribution No. 954 CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................................................v Abstract ..............................................................................................................................vi Chapter 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................1 Chapter 2 . Description of the Study Methods ................................................................4 Data Collection ....................................................................................................................4 Description -

Ndcc Media Update

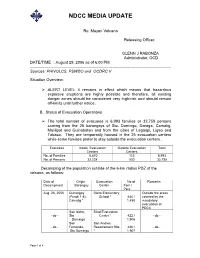

NDCC MEDIA UPDATE Re: Mayon Volcano Releasing Officer: GLENN J RABONZA Administrator, OCD DATE/TIME : August 29, 2006 as of 6:00 PM ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Sources: PHIVOLCS, PSWDO and OCDRC V Situation Overview. ALERT LEVEL 4 remains in effect which means that hazardous explosive eruptions are highly possible and therefore, all existing danger zones should be considered very high-risk and should remain off-limits until further notice. B. Status of Evacuation Operations The total number of evacuees is 6,993 families or 32,758 persons coming from the 26 barangays of Sto. Domingo, Daraga, Camalig, Malilipot and Guinobatan and from the cities of Legaspi, Ligao and Tabaco. They are temporarily housed in the 25 evacuation centers while some families prefer to stay outside the evacuation centers . Evacuees Inside Evacuation Outside Evacuation Total Centers Centers No. of Families 6,870 123 6,993 No. of Persons 32,228 530 32,758 Decamping of the population outside of the 6-km radius PDZ of the volcano, as follows: Date of Origin Evacuation No of Remarks Decampment Barangay Center Fam / Pers Aug. 26, 2006 Quirangay Bariw Elementary Outside the areas (Purok 1-5), School * 444 / covered by the Camalig * 1,450 mandatory evacuation of PDCC San Isidro, Bical Evacuation - do - Sto Center * 422 / - do - Domingo 1,906 San San Andres - do - Fernando, Resettlement Site 446 / - do - Sto Domingo * 1,907 Page 1 of 4 NDCC MEDIA UPDATE Date of Origin Evacuation No of Remarks Decampment Barangay Center Fam / Pers Aug. 28, 2006 Salvacion, Tagas Daraga Elementary 345 / 1,043 - do - Sch. - do - Miisi, Daraga Upper Malabog Elem. -

Provincial Government of Albay and the Center for Initiatives And

Strengthening Climate Resilience Provincial Government of Albay and the SCR Center for Initiatives and Research on Climate Adaptation Case Study Summary PHILIPPINES Which of the three pillars does this project or policy intervention best illustrate? Tackling Exposure to Changing Hazards and Disaster Impacts Enhancing Adaptive Capacity Addressing Poverty, Vulnerabil- ity and their Causes In 2008, the Province of Albay in the Philippines was declared a "Global Local Government Unit (LGU) model for Climate Change Adapta- tion" by the UN-ISDR and the World Bank. The province has boldly initiated many innovative approaches to tackling disaster risk reduction (DRR) and climate change adaptation (CCA) in Albay and continues to integrate CCA into its current DRM structure. Albay maintains its position as the first mover in terms of climate smart DRR by imple- menting good practices to ensure zero casualty during calamities, which is why the province is now being recognized throughout the world as a local govern- ment exemplar in Climate Change Adap- tation. It has pioneered in mainstreaming “Think Global Warming. Act Local Adaptation.” CCA in the education sector by devel- oping a curriculum to teach CCA from -- Provincial Government of Albay the primary level up which will be imple- Through the leadership of Gov. Joey S. Salceda, Albay province has become the first province to mented in schools beginning the 2010 proclaim climate change adaptation as a governing policy, and the Provincial Government of Albay schoolyear. Countless information, edu- cation and communication activities have (PGA) was unanimously proclaimed as the first and pioneering prototype for local Climate Change been organized to create climate change Adaptation. -

Cruising Guide to the Philippines

Cruising Guide to the Philippines For Yachtsmen By Conant M. Webb Draft of 06/16/09 Webb - Cruising Guide to the Phillippines Page 2 INTRODUCTION The Philippines is the second largest archipelago in the world after Indonesia, with around 7,000 islands. Relatively few yachts cruise here, but there seem to be more every year. In most areas it is still rare to run across another yacht. There are pristine coral reefs, turquoise bays and snug anchorages, as well as more metropolitan delights. The Filipino people are very friendly and sometimes embarrassingly hospitable. Their culture is a unique mixture of indigenous, Spanish, Asian and American. Philippine charts are inexpensive and reasonably good. English is widely (although not universally) spoken. The cost of living is very reasonable. This book is intended to meet the particular needs of the cruising yachtsman with a boat in the 10-20 meter range. It supplements (but is not intended to replace) conventional navigational materials, a discussion of which can be found below on page 16. I have tried to make this book accurate, but responsibility for the safety of your vessel and its crew must remain yours alone. CONVENTIONS IN THIS BOOK Coordinates are given for various features to help you find them on a chart, not for uncritical use with GPS. In most cases the position is approximate, and is only given to the nearest whole minute. Where coordinates are expressed more exactly, in decimal minutes or minutes and seconds, the relevant chart is mentioned or WGS 84 is the datum used. See the References section (page 157) for specific details of the chart edition used. -

Seaweed-Associated Fishes of Lagonoy Gulf in Bicol, the Philippines -With Emphasis on Siganids (Teleoptei: Siganidae)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kochi University Repository Kuroshio Science 2-1, 67-72, 2008 Seaweed-associated Fishes of Lagonoy Gulf in Bicol, the Philippines -with Emphasis on Siganids (Teleoptei: Siganidae)- Victor S. Soliman1*, Antonino B. Mendoza, Jr.1 and Kosaku Yamaoka2 1 Coastal Resouces management Unit, Bicol University Tabaco Campus, (Tabaco, Albay 4511, Philippines) 2 Graduate School of Kuroshio Science, Kochi University (Monobe, Nankoku, Kochi 783-8502, Japan) Abstract Lagonoy Gulf is a major fishing ground in the Philippines. It is large (3071 km2) and deep (80% of its area is 800-1200 m) where channels opening to the Pacific Ocean are entrenched. Its annual fishery production of 26,000 MT in 1994 slightly decreased to 20,000 MT in 2004. During the same 10-year period, catches of higher order, predatory fishes decreased and were replaced by herbivores and planktivores. Scombrids such as tunas and mackerels composed 51-54% of total harvest. Of the 480 fish species identified in the gulf, 131 or 27% are seaweed-associated or these fishes have utilized the seaweed habitat for juvenile settlement, refuge, breeding and feeding sites. The seaweeds occupy solely distinct beds (e.g., Sargassum) or overlap with seagrass and coral reef areas. About half of all fishes (49.6% or 238 species) are coral reef fishes. The most speciose fish genera are Chaetodon (19 spp.), Lutjanus (18 spp.), Pomacentrus (17 spp.) and Siganus (14 spp.). Among them, Siganus (Siganids or rabbitfishes) is the most speciose, commercially-important genus contributing 560 mt-yr-1 to the total fishery production, including about 60 mt siganid juvenile catch. -

Integrated Bicol River Basin Management and Development Master Plan

Volume 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Integrated Bicol River Basin Management and Development Master Plan July 2015 With Technical Assistance from: Orient Integrated Development Consultants, Inc. Formulation of an Integrated Bicol River Basin Management and Development Master plan Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 2.0 KEY FEATURES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BICOL RIVER BASIN ........................... 1 3.0 ASSESSMENT OF EXISTING SITUATION ........................................................................ 3 4.0 DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES ................................................... 9 5.0 VISION, GOAL, OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES ........................................................... 10 6.0 INVESTMENT REQUIREMENTS ................................................................................... 17 7.0 ECONOMIC ANALYSIS ................................................................................................. 20 8.0 ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF PROPOSED PROJECTS ....................................... 20 Vol 1: Executive Summary i | Page Formulation of an Integrated Bicol River Basin Management and Development Master plan 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Bicol River Basin (BRB) has a total land area of 317,103 hectares and covers the provinces of Albay, Camarines Sur and Camarines Norte. The basin plays a significant role in the development of the region because of the abundant resources within it and the ecological -

Malacañang Manila Proclamation No. 1250

MALACAÑANG MANILA PROCLAMATION NO. 1250 EXCLUSION OF MINERAL RESOURCE-RICH AREAS OF CAGRARAY ISLAND, ALBAY FROM THE BICOL REGION TOURISM MASTER PLAN WHEREAS, the Bicol Region Tourism Master Plan (BRTMP) serves as the blueprint for the development and promotion of tourism in the Bicol Region, the implementation of which will generate livelihood and employment opportunities therein; WHEREAS, the BRTMP embraces mineral resource-rich areas found in the Island of Cagraray, Albay Province; WHEREAS, the inclusion of these mineral resource-rich areas in the BRTMP precludes the utilization and development of the island's mineral resources and caused the cessation of exploratory mining and related activities, thereby depriving investors of the return on their investments and the local residents of employment opportunities; WHEREAS, the sustainable development and utilization of natural resources, which includes mineral resources, is being promoted and encouraged by the government in accordance with the Philippine Mining Act (RA No. 7942, s. 1995); NOW THEREFORE, I, FIDEL V. RAMOS, President of Philippines, by virtue of the powers vested in me by law do hereby declare and order: SECTION 1. Exclusion Of Mineral Resource-Rich Areas in Cagraray Island from the Coverage of the BRTMP. Upon the recommendation of the Regional Technical Working Group (RTWG) composed of representatives from the regional offices of the Department of Tourism, National Economic and Development Authority, Presidential Commission on Bicol Tourism Special Development Project, and representatives from the Provincial Government of Albay, Municipal Government of Bacacay, Albay Provincial and Bacacay Municipal Tourism Councils, and 1 in consultation with the concerned local communities, the mineral- rich areas in Cagraray Island as delineated in the attached map which forms part and parcel of this document, are hereby excluded from the coverage of the Bicol Region Tourism Master Plan. -

Actual Census Pop. 2015 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 REGION V

Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: Actual Census Pop. 2015 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 REGION V - BICOL REGION 5,796,989 6,266,652 6,387,680 6,511,148 6,637,047 6,766,622 ALBAY 1,314,826 1,404,477 1,428,207 1,452,261 1,476,639 1,501,348 0.033530 0.027955 0.025166 0.023484 0.022356 BACACAY 68,906 73,604 74,848 76,109 77,386 78,681 Baclayon 2,703 2,887 2,936 2,986 3,036 3,086 Banao 1,491 1,593 1,620 1,647 1,674 1,703 Bariw 625 668 679 690 702 714 Basud 1,746 1,865 1,897 1,929 1,961 1,994 Bayandong 1,650 1,763 1,792 1,822 1,853 1,884 Bonga (Upper) 7,649 8,171 8,309 8,449 8,590 8,734 Buang 1,337 1,428 1,452 1,477 1,502 1,527 Cabasan 2,028 2,166 2,203 2,240 2,278 2,316 Cagbulacao 862 921 936 952 968 984 Cagraray 703 751 764 776 790 803 Cajogutan 1,130 1,207 1,227 1,248 1,269 1,290 Cawayan 1,247 1,332 1,355 1,377 1,400 1,424 Damacan 431 460 468 476 484 492 Gubat Ilawod 1,080 1,154 1,173 1,193 1,213 1,233 Gubat Iraya 1,159 1,238 1,259 1,280 1,302 1,323 Hindi 3,800 4,059 4,128 4,197 4,268 4,339 Igang 2,332 2,491 2,533 2,576 2,619 2,663 Langaton 765 817 831 845 859 874 Manaet 836 893 908 923 939 955 Mapulang Daga 453 484 492 500 509 517 Mataas 518 553 563 572 582 591 Misibis 1,007 1,076 1,094 1,112 1,131 1,150 Nahapunan 402 429 437 444 451 459 Namanday 1,482 1,583 1,610 1,637 1,664 1,692 Namantao 778 831 845 859 874 888 Napao 1,883 2,011 2,045 2,080 2,115 2,150 Panarayon 1,848 1,974 2,007 2,041 2,075 2,110 Pigcobohan 817 873 887 902 918 933 Pili Ilawod 1,522 1,626 1,653 1,681 1,709 1,738 Pili Iraya 997 1,065 1,083 1,101 -

Assessment of the Fisheries of Lagonoy Gulf (Region 5)

ASSESSMENT OF THE FISHERIES OF LAGONOY GULF (REGION 5) VIRGINIA L. OLAÑO, MARIETTA B. VERGARA and FE L. GONZALES ASSESSMENT OF THE FISHERIES OF LAGONOY GULF (REGION 5) VIRGINIA L. OLAÑO Project Leader, National Stock Assessment Program (NSAP) Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, Region 5 (BFAR 5) San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur MARIETTA B. VERGARA Assistant Project Leader, NSAP BFAR 5, San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur and FE L. GONZALES Co-Project Leader BFAR-National Fisheries Research and Development Institute Kayumanggi Press Building, Quezon Avenue, Quezon City Assessment of the Fisheries of Lagonoy Gulf CONTENTS List of Tables iii List of Figures iv List of Abbreviations, Acronyms and Symbols vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS viii ABSTRACT ix INTRODUCTION 1 Objectives of the Study 3 General 3 Specific 3 METHODOLOGY 4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 6 Boat and Gear Inventory 6 Production Estimates 6 Catch Composition 6 Dominant Fish Families 6 Dominant Fish Species 7 Catch Composition of the Major Types of Fishing Gear 8 Catch Contribution of the Major Types of Fishing Gear 13 Seasonality of Species 15 Catch Per Unit Effort 17 Surplus Production 17 Estimation of Population Parameters 18 Relative Yield Per Recruit 21 Probability of Capture and Virtual Population Analysis 22 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 27 REFERENCES 30 ii Assessment of the Fisheries of Lagonoy Gulf TABLES Table 1 Production estimates by gear based on boat and gear inventory in Lagonoy Gulf (June to December 2001 7 Table 2 Dominant fish and invertebrate species caught by major gear -

DENR-BMB Atlas of Luzon Wetlands 17Sept14.Indd

Philippine Copyright © 2014 Biodiversity Management Bureau Department of Environment and Natural Resources This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the Copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. BMB - DENR Ninoy Aquino Parks and Wildlife Center Compound Quezon Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City Philippines 1101 Telefax (+632) 925-8950 [email protected] http://www.bmb.gov.ph ISBN 978-621-95016-2-0 Printed and bound in the Philippines First Printing: September 2014 Project Heads : Marlynn M. Mendoza and Joy M. Navarro GIS Mapping : Rej Winlove M. Bungabong Project Assistant : Patricia May Labitoria Design and Layout : Jerome Bonto Project Support : Ramsar Regional Center-East Asia Inland wetlands boundaries and their geographic locations are subject to actual ground verification and survey/ delineation. Administrative/political boundaries are approximate. If there are other wetland areas you know and are not reflected in this Atlas, please feel free to contact us. Recommended citation: Biodiversity Management Bureau-Department of Environment and Natural Resources. 2014. Atlas of Inland Wetlands in Mainland Luzon, Philippines. Quezon City. Published by: Biodiversity Management Bureau - Department of Environment and Natural Resources Candaba Swamp, Candaba, Pampanga Guiaya Argean Rej Winlove M. Bungabong M. Winlove Rej Dumacaa River, Tayabas, Quezon Jerome P. Bonto P. Jerome Laguna Lake, Laguna Zoisane Geam G. Lumbres G. Geam Zoisane -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized CDD and Social Capital Impact Designing a Baseline Survey in the Philippines Copyright © 2005 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C., 20433, USA All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First Printing May 2005 This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, and e-mail [email protected]. -

Regional Office No. V

MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU - Regional Office No. V PHYSICAL ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT AS OF MARCH 2017 Programs, Activity and Projects Performance Indicator (PI)/ Annual MARCH % % Accom. (PAPs) Unit of Work of Measure(UWM) Target TARGET ACCOMPLISHMENT As of as to REMARKS (1) (2) (3) This Month To-date This Month To-date To-date Annual A.01 GENERAL ADMINISTRATION AND SUPPORT SERVICES A.01.a General Management and Supervision 1. Administrative Services a. Management and Administrative Reports submitted (no.) 12 1 3 1 3 100.00 25.00 Support Service b. Housekeeping, Building and Ground Reports submitted (no.) 12 1 3 1 3 100.00 25.00 Improvement Service c. Human Resource Management Service Reports submitted (no.) 12 1 3 1 3 100.00 25.00 d. Solid Waste Management Service Solid waste management plan implemented (no.) 12 1 3 1 3 100.00 25.00 e. Implementation of Government Reports submitted (no.) 12 1 3 1 3 100.00 25.00 Procurement f. Cashiering Reports of LDDAP-ADA issued (no.) 12 1 3 1 3 100.00 25.00 Paid payrolls and ADA prepared (no.) 12 1 3 1 3 100.00 25.00 Advice of checks issued and cancelled 12 1 3 1 3 100.00 25.00 (no.) Report of remittance of collections and deposit to Treasury (no.) 12 1 3 1 3 100.00 25.00 Report on Revenue Collection (no.) 12 1 3 1 3 100.00 25.00 A.01.b Financial Management Service a. Budget Proposals a.1 Forward Estimates Forward Estimates submitted (no.) 4 0.00 a.2 Budget Proposal and Report Forms Proposed budget submitted (no.) a.