Sustaining Responsible Tourism: the Case of Kerala, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accused Persons Arrested in Idukki District from 18.12.2016 to 24.12.2016

Accused Persons arrested in Idukki district from 18.12.2016 to 24.12.2016 Name of the Name of Name of the Place at Date & Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police Arresting father of Address of Accused which Time of which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Officer, Rank Accused Arrested Arrest accused & Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 KUZHIKKATTU HOUSE 587/16 U/S CHEENKALLU 18/12/216 KARIMANNO Bailed by 1 BIJU MATHEW 43/16,MALE PANNOOR 279 IPC 185 N.P BABY BHAGAM 11.05 OR Police OF MV ACT NEYYASSERY PO NEYYASSERY Ullattu(h), Cr. 477/16. V.D. Joseph. Age Vathikudy Bhagam, Moonnambloc 18.12.2016 U/s 279 IPC, SI of Police 2 Joby John 33/16. Murickassery JFMC Idukki Padamugham Kara, k . 11.20 Hrs 3(1) R/w 181 Murickassery Male Vathikudy Village of MV Act PS Cr. 639/16, Puthenveettil, Baby Male, 18-12-16 ; U/s 279 IPC, 3 Aminesh Joy Heaven Valley, Upputhara Upputhara Ulahannan. Bailed age 33 10.30 3 (1) r/w 181 Anavilasam Village SI of Police MV Act Rajeshbhavan, Baby Male, Kavukkulam, Fair 18-12-16 ; 640/16 U/s 4 Rajesh Varghese Mecherikkada Upputhara Ulahannan. Bailed age 36 field, Elapapra 11.10 15 (c ) of SI of Police Village Kavakkulam Estate Baby Male, lanes Kavukkulam, 18-12-16 ; 640/16 U/s 5 Kanakaraj Rajamani Mecherikkada Upputhara Ulahannan. Bailed age 36 Fair field, Elapapra 11.10 15 (c ) of SI of Police Village Kavakkulam Estate Baby Male, lanes Kavukkulam, 18-12-16 ; 640/16 U/s 6 Rajendran Sivan Njanam Mecherikkada Upputhara Ulahannan. -

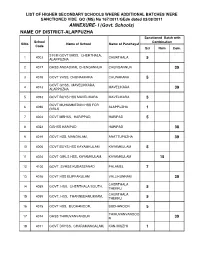

ANNEXURE- I (Govt. Schools) NAME of DISTRICT-ALAPPUZHA Sanctioned Batch with School Combination Slno Name of School Name of Panchayat Code Sci Hum Com

LIST OF HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOLS WHERE ADDITIONAL BATCHES WERE SANCTIONED VIDE GO (MS) No 167/2011/GEdn dated 03/08/2011 ANNEXURE- I (Govt. Schools) NAME OF DISTRICT-ALAPPUZHA Sanctioned Batch with School Combination SlNo Name of School Name of Panchayat Code Sci Hum Com. S N M GOVT BHSS, CHERTHALA, 1 4003 CHERTHALA ALAPPUZHA 5 2 4017 GHSS ANGADIKAL CHENGANNUR CHENGANNUR 39 3 4018 GOVT VHSS, CHUNAKKARA CHUNAKARA 5 GOVT GHSS, MAVELIKKARA, 4 4013 MAVELIKARA ALAPPUZHA 39 5 4093 GOVT BOYS HSS MAVELIKARA MAVELIKARA 5 GOVT MUHAMMEDAN HSS FOR 6 4098 ALAPPUZHA GIRLS 1 7 4004 GOVT MBHSS, HARIPPAD, HARIPAD 5 8 4023 GGHSS HARIPAD HARIPAD 38 9 4019 GOVT HSS, MANGALAM, ARATTUPUZHA 39 10 4006 GOVT BOYS HSS KAYAMKULAM KAYAMKULAM 5 11 4024 GOVT GIRLS HSS, KAYAMKULAM, KAYAMKULAM 15 12 4100 GOVT. SVHSS KUDASSANAD PALAMEL 7 13 4016 GOVT HSS ELIPPAKULAM VALLIKUNNAM 39 CHERTHALA 14 4089 GOVT. HSS, CHERTHALA SOUTH, THEKKU 5 CHERTHALA 15 4099 GOVT. HSS, THANNEERMUKKAM, THEKKU 5 16 4015 GOVT HSS, BUDHANOOR, BUDHANOOR 5 THIRUVANVANDOO 17 4014 GHSS THIRUVANVANDUR R 39 18 4011 GOVT DVHSS, CHARAMANGALAM, KANJIKUZHI 1 1 19 4001 GOVT HSS, ALA, ALAPPUZHA ALA 20 4020 GOVT HSS, AYAPARAMBU, CHERUTHANA 5 21 4026 GOVT VHSS, MULAKKUZHA, MULAKUZHA 39 NAME OF DISTRICT-IDUKKI Sanctioned Batch with School SlNo Name of School Name of Panchayat Combination Code Sci Hum Com 1 6003 GOVT HSS, KALLAR, IDUKKI PAMPADUMPARA 39 GOVT. HSS, PANIKKANKUDY, 2 6057 KONNATHADI, KONNATHADI 34 GOVT GHSS, THODUPUZHA, 3 6010 IDUKKI THODUPUZHA(M) 39 4 6067 GHSS KATTAPPNA KATTAPANA 34 5 6001 GHSS AMARAVATHY, KUMILY KUMILY 5 6 6004 GOVT HSS, KUMILI, IDUKKI KUMILY 39 7 6062 PANCHAYATH HSS, VANDIPERIYAR VANDIPERIYAR 38 8 6013 GOVT HSS, KUDAYATHUR, IDUKKI KUDAYATHUR 39 9 6055 GOVT HSS THOPRANKUDY VATHIKUDI 39 10 6016 N.S.P HSS PUTTADY VANDANMEDU 2 11 6056 GT HSS PERINGASSERY UDUMBANNOOR 16 NAME OF DISTRICT-KANNUR Sanctioned Batch with School SlNo Name of School Name of Panchayat Combination Code Sci Hum Com 1 13011 GOVT HSS, PALLIKKUNNU, KANNUR Pallikunnu 1 GOVT. -

The Kerala Cardamom Prooessing & Marketing Company Ltd

FORM - D (See Condition (5) of Form B I) Advance Auction Report The Kerala Cardamom Prooessing & Marketing Company Ltd., Spice House, Thekkady., S B L No. AU/CS/T161!008/2015 I Season 2017-2018 2 Auction Number 32 3 Auction Date November 23, 2017 4 Qty. Carried over from previous Auction Nil 5 Fresh Arrivals ( Kgs.) 95614.600 6 Qty. Put for Auction 95614.600 7 Qty. Withdrawn ( Kgs.) 29.100 8 Qty. Returned to Planters 29.100 9 Total Qty. Sold (Kgs.) 95585.500 10 Balance with the Auctioneer Nil 11 Total Value of Sales (Rs.) 87071682.05 12 Maximum (Rs./Kg) 1288.00 13 Minimum (Rs./Kg) 802.00 14 Average (Rs./Kg) 910.93 Signature of the Auctioneer Name of the 5 Hiqhest Bidders 1 Mohith Krishnaa Cardamom, Bodinayakanur- 625513. 6427.900 5879166.55 2 The Kerala Cardamom Processing&Mktg Company Ltc 5285.000 4853835.70 3 Shri cardamom Trading Company,Bodiyayakanur-625 4854.100 4362150.50 4 Rajam Company, Bodinayakanur - 625513 4775 100 4448246.70 5 John Jacob & Co., Mattancherry, Kochi -2 (H.o) 4764.900 4322850.10 01 21$' The K.C.P.M.0 Ltd., Thekkady 40 Auction No. 32 S Dated 23/11/2017 S Total Average Rate 910.93 Maximum Rate 1288.00 S Minimum Rate e02. p0 Total Arrivals 95614;600 Kgs. S Withdrawal Quantity 29.100 Kgs. S otal Sales Quantity 95585.500 Kgs. A Grade Average Rate 0.00 S A Grade Maximum 0.00 --> Weight 0.000 Kgs. A Grade Minimum 919.00 ---> Weight 0.000 Kgs. -

Report on Visit to Vembanad Kol, Kerala, a Wetland Included Under

Report on Visit to Vembanad Kol, Kerala, a wetland included under the National Wetland Conservation and Management Programme of the Ministry of Environment and Forests. 1. Context To enable Half Yearly Performance Review of the programmes of the Ministry of Environment & Forests, the Planning Commission, Government of India, on 13th June 2008 constituted an Expert Team (Appendix-1) to visit three wetlands viz. Wular Lake in J&K, Chilika Lake in Orissa and Vembanad Kol in Kerala, for assessing the status of implementation of the National Wetland Conservation and Management Programme (NWCMP). 2. Visit itinerary The Team comprising Dr.(Mrs.) Indrani Chandrasekharan, Advisor(E&F), Planning Commission, Dr. T. Balasubramanian, Director, CAS in Marine Biology, Annamalai University and Dr. V. Sampath, Ex-Advisor, MoES and UNDP Sr. National Consultant, visited Vembanad lake and held discussions at the Vembanad Lake and Alleppey on 30 June and 1st July 2008. Details of presentations and discussions held on 1st July 2008 are at Appendix-2. 3. The Vembanad Lake Kerala has a continuous chain of lagoons or backwaters along its coastal region. These water bodies are fed by rivers and drain into the Lakshadweep Sea through small openings in the sandbars called ‘azhi’, if permanent or ‘pozhi’, if temporary. The Vembanad wetland system and its associated drainage basins lie in the humid tropical region between 09˚00’ -10˚40’N and 76˚00’-77˚30’E. It is unique in terms of physiography, geology, climate, hydrology, land use and flora and fauna. The rivers are generally short, steep, fast flowing and monsoon fed. -

Need for Tourism Infrastructure Development in Alappuzha

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 7, July-2014 ISSN 2229-5518 71 Need for tourism infrastructure development in Alappuzha Minu Paul C Smitha M.V. Department of Architecture Department of Architecture College of Engineering Trivandrum College of Engineering Trivandrum Trivandrum, India Trivandrum, India [email protected] [email protected] Abstract - This paper intends to bring about the need to “Fig.2” it is clear that number of tourist arrivals to bring about tourism infrastructure development in Alappuzha Alappuzha is not showing a positive indication to tourism in so as to enhance tourist arrivals and revenue there by bringing Alappuzha. about local economic development. Strategies are proposed to enhance tourist arrivals and upgrade tourism infrastructure from the inferences arrived at from primary and secondary studies. Keywords – tourism infrastructure, potentials I. INTRODUCTION : TOURISM IN KERALA According to National Geographic traveller, Kerala is one of the “50 must see destinations of a lifetime”. Tourist inflow to Kerala is mainly contributed by domestic tourists. As per tourism statistics 2010, 58% of the domestic tourists are accounted by three districts namely Ernakulam, Thrissur and Thiruvananthapuram. Thiruvananthapuram and Fig 2: Tourist flow in leading tourist destinations Ernakulam contribute to 73%IJSER of total international tourists. Source: Tourism Statistics, 2011 “Fig.1” shows that as per tourism statistics 2010, Alappuzha contributes 6.37% to the total share of tourist flow to Kerala. II. TOURISM IN ALAPPUZHA Alappuzha is a Land Mark between the broad Arabian Sea and a net work of rivers flowing into it. In the early first decade of the 20th Century the then Viceroy of the Indian Empire, Lord Curzon made a visit in the State to Alleppey, now Alappuzha. -

Periyar Tiger Reserve

PERIYAR TIGER RESERVE Periyar Tiger Reserve (PTR) along with adjoining protected areas form the largest tiger conservation landscape in Southern most Western Ghats, extending over an extent of 4078 sq kms in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. It has a long history of conservation since 1934. The Periyar Tiger Reserve is managed under two Divisions, namely, Periyar East and West Divisions. The visitors point is at Thekkady in the East Division. It spreads across three Revenue Districts viz; Idukki, Pathanamthitta and Kottayam in the State of Kerala. The Protected area comprises of Periyar Lake Reserve, Mount Plateau RF, Rattendon Valley RF, Ranni RF and Gudrikkal RF. Area of the Tiger Reserve Core/Critical Tiger Habitat : 881 sq km Buffer : 44 sq km Total : 925 sq km Location Latitudes : 9 0 17’ 56.04” and 9 0 37” 10.2” N Longitudes : 76 0 56’ 12.12” and 77 0 25’ 5.52” E Map Habitat Attributes The terrain is Hilly and undulating with a maximum altitude of 2016 m. Two major rivers namely Periyar and Pamba drain the area. Mullaperiyar Dam is located within the PTR. The vegetation comprises of Tropical evergreen forests, semi- evergreen forests, Moist deciduous Forests, Transitional fringe ever green forests, grass lands and eucalyptus plantations. Tropical evergreen forest is the dominant vegetation spread over 337 sq km (38.2%). Semi-ever green forests and grass land are more or less equal in extent (each more than 25%). Relic Eucalyptus plantation (that was earlier part of former Grassland Afforestation Division), beyond the third rotation age exists along with grass lands and natural forest over 30 sq kms area. -

Eco-Tourism in Kerala and Its Importance and Sustainability

Volume : 3 | Issue : 5 | May 2014 ISSN - 2250-1991 Research Paper Economics ECO-Tourism In Kerala and Its Importance and Sustainability Assistant professor, Post Graduate Department of Economics Dr. Haseena V.A M.E.S Asmabi College, P.Vemballur, Kodunagllur, Thrissur, Kerala Tourism is one of the few sectors where Kerala has clear competitive advantages given its diverse geography in a short space ranging from the Western Ghats covered with dense forests to the backwaters to the Arabian sea. Its ancient rich culture including traditional dance forms and the strong presence of alternative systems of medicine add to its allure. Unfortunately, Kerala is dominated by domestic tourism within the state although foreign tourists arrivals to the state has been growing at a faster rate than national average. The goal in the KPP 2030 is to develop Kerala as an up-market tourism destination with the state being the top destination in terms of number of tourists and revenue among all the Indian states. Sustainable tourism is the mission. This can be achieved by integrating tourism with other parts of the economy like medical and health hubs which will attract more stable tourists over a longer period of time and with higher spending capacity. There will be new elements added to leisure tourism and niche products in tourism will be developed. Infrastructure development is ABSTRACT crucial to achieve this goal. The success of Kerala tourism will be based on the synergy between private and public sectors. The government has taken steps to encourage private investment in tourism, while adhering to the principles and practices of sustainability. -

Lessons from Periyar Tiger Reserve in Kerala State, India

TROPICS Vol. 17 (2) Issued April 30, 2008 Implementation process of India Ecodevelopment Project and the sustainability: Lessons from Periyar Tiger Reserve in Kerala State, India * Ellyn K. DAMAYANTI and Misa MASUDA Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Japan *Corresponding author: Tel: +81−29−853−4610/Fax: +81−29−853−4761, E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Protected areas in developing involvement of local people, and it has been applied countries have been in a dilemma between to various parts of developing countries with similar biodiversity conservation and improvement of situations. Based on the varied local conditions, ICDPs local livelihood. The study aims to examine the have been applied from small to large-scale with different sustainability of India Ecodevelopment Project (IEP) degrees of people’s involvement and various types of in Periyar Tiger Reserve (PTR), Kerala, through funding mechanisms. analyzing kinds of financial mechanisms that However, Wells et al. (1992) who studied the initial were provided by the project, how IEP had been stage of ICDP implementation in 23 projects in Africa, implemented, and what kind of changes emerged Asia and Latin America concluded that even under the in the behaviors and perceptions of local people. best conditions ICDPs could play only a modest role in The results of secondary data and interviews with mitigating the powerful forces causing environmental key informants revealed that organizing people into degradation. Through lessons learned from Southeast Ecodevelopment Committees (EDCs) in the IEP Asia, MacKinnon and Wardojo (2001) suggested the implementation has resulted positive impacts in factors for the success of ICDP, which can be summarized terms of reducing offences and initiating regular as: 1) clear demarcation of the area, 2) capacity of involvement of local people in protection activities. -

IDUKKI Contact Designation Office Address Phone Numbers PS Name of BLO in LAC Name of Polling Station Address NO

IDUKKI Contact Designation Office address Phone Numbers PS Name of BLO in LAC Name of Polling Station Address NO. charge office Residence Mobile Grama Panchayat 9495879720 Grama Panchayat Office, 88 1 Community Hall,Marayoor Grammam S.Palani LDC Office, Marayoor. Marayoor. Taluk Office, Taluk Office, 9446342837 88 2 Govt.L P School,Marayoor V Devadas UDC Devikulam. Devikulam. Krishi Krishi Bhavan, Bhavan, 9495044722 88 3 St.Michale's L P School,Michalegiri Annas Agri.Asst marayoor marayoor Grama Panchayat 9495879720 St.Mary's U P School,Marayoor(South Grama Panchayat Office, 88 4 Division) S.Palani LDC Office, Marayoor. Marayoor. St.Mary's U P School,Marayoor(North Edward G.H.S, 9446392168 88 5 Division) Gnanasekar H SA G.H.S, Marayoor. Marayoor. St.Mary's U P School,Marayoor(Middle Edward G.H.S, 9446392168 88 6 Division) Gnanasekar H SA G.H.S, Marayoor. Marayoor. Taluk Office, Taluk Office, 9446342837 88 7 St.Mary's L P School,Pallanad V Devadas UDC Devikulam. Devikulam. Krishi Krishi Bhavan, Bhavan, 9495044722 88 8 Forest Community Hall,Nachivayal Annas Agri.Asst marayoor marayoor Grama Panchayat 4865246208 St.Pious L P School,Pious Nagar(North Grama Panchayat Office, 88 9 Division) George Mathai UDC Office, Kanthalloor Kanthalloor Grama Panchayat 4865246208 St.Pious L P School,Pious Nagar(East Grama Panchayat Office, 88 10 Division) George Mathai UDC Office, Kanthalloor Kanthalloor St.Pious U P School,Pious Nagar(South Village Office, Village Office, 9048404481 88 11 Division) Sreenivasan Village Asst. Keezhanthoor. Keezhanthoor. Grama -

A Study on Significance of Backwater Tourism and Safe Houseboat

Munich Personal RePEc Archive A Study on Significance of Backwater Tourism and Safe Houseboat Operation in Kerala Jose, Jiju and Aithal, Sreeramana College of Management and Commerce, Srinivas University, Mangalore, India 4 August 2020 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/102871/ MPRA Paper No. 102871, posted 13 Sep 2020 20:03 UTC A Study on the Significance of Backwater Tourism and Safe Houseboat Operations in Kerala Jiju Jose* & P. S. Aithal** *Research Scholar, College of Management and Commerce, Srinivas University, Mangalore, India E-mail : [email protected] **Professor, College of Management & Commerce, Srinivas University, Mangalore, India E-mail : [email protected] August 2020 ABSTRACT The Backwaters of Kerala are historically important. The backwaters and interconnecting navigable canals have made a number of rural tourism destinations with matchless beauty. These backwater systems were once Kerala’s own trade highways. The major component of backwater tourism is houseboat cruising. The State has sensed the potential of backwater tourism in nowadays. Mass tourism movement in this sector caused for the multidimensional impacts on the economic, socio-cultural and bio-physical environment. Being an Eco-tourism product, backwater tourism needs sustainable and responsible tourism practice. Considering the need for the sustenance of the houseboat operation as a unique tourism product, it is mandatory to ensure the quality of facilities and services. In this paper, the researcher is trying to focus on the importance of backwater tourism in Kerala. Also giving special attention to identify various aspects of safe houseboat operations and the issues related. The major issues related to houseboat operation are lack of infrastructure, issues of licensing, issues of safety, environmental issues, and lack of quality services. -

Factsheet-Thekkady Copy

Niraamaya Retreats Thekkady is a secluded living sanctuary within a spice plantation nestled in the mountains and wrapped in the cool embrace of a tropical rainforest. Spread amongst 8 acres of cardamom plantations, this truly boutique experience offers 13 independent cottages garden-view and mountain-view style giving magnificent scenes of the valley and the verdant mountains. Niraamaya’s acclaimed spa offers a host of Ayurveda and International treatments to nurture any concerns and remedies any ailments in the process. Café Samsara is an all-day dining restaurant featuring global and regional cuisine. For the more adventurous traveller, Thekkady offers several options like jeep safaris, trekking, bamboo rafting, cultural shows, spice walks and shopping trips. ACCOMMODATION Garden View Cottages The retreat offers 8 plantation-styled cottages with mesmerising views of the garden and the verdant mountains around the vicinity. Each cottage is equipped with modern amenities and premium accessories to elevate one’s stay like an enchanting private sit-out and eloquent craftsmanship with its décor. Mountain-view Cottages These 5 exclusive private cottages are built on stilts and is made from Bangkirai wood offering majestic view of the mountains. The floor-to-ceiling windows succeed in showcasing breath-taking visions at the break of dawn or during sun sets in the midst of a rustic landscape. The cottages are set in a line overlooking the valley bordering the Periyar Wildlife sanctuary. FOOD & BEVERAGE Café Samsara is an all-day dining destination offering a delectable combination of global best-sellers, traditional Kerala’s culinary dishes, Pan Asian delicacies and custom made fares. -

Tourist Statistics 2019 (Book)

KERALA TOURISM STATISTICS 2019 RESEARCH AND STATISTICS DIVISION DEPARTMENT of TOURISM GOVERNMENT OF KERALA DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM KERALA TOURISM STATISTICS 2019 Prepared by RESEARCH & STATISTICS DIVISION DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM Sri.KADAKAMPALLY SURENDRAN Minister for Devaswoms, Tourism and Co-Operation, Kerala Ph (Office): 0471-2336605, 2334294 Thiruvananthapuram MESSAGE Kerala is after all India’s most distinguished state. This land of rare natural beauty is steeped in history and culture, but it has still kept up with the times, Kerala has taken its tourism very seriously. It is not for nothing than that the Eden in these tropics; God’s own country was selected by National Geographic Traveler as one of its 50 “destination of life time”. When it comes to building a result oriented development programme, data collection is key in any sector. To capitalize the opportunity to effectively bench mark, it is essential to collect data’s concerned with the matter. In this context statistical analysis of tourist arrivals to a destination is gaining importance .We need to assess whether the development of destination is sufficient to meet the requirements of visiting tourists. Our plan of action should be executed in a meticulous manner on the basis of the statistical findings. Kerala Tourism Statistics 2019 is another effort in the continuing process of Kerala Tourism to keep a tab up-to-date data for timely action and effective planning, in the various fields concerned with tourism. I wish all success to this endeavor. Kadakampally Surendran MESSAGE Kerala Tourism has always attracted tourists, both domestic and foreign with its natural beauty and the warmth and hospitality of the people of Kerala.