SC09-1676 Petitioner, 4 DCA CASE NO.: 4D08-3612 Vs. DO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property Owner's List (As of 10/26/2020)

Property Owner's List (As of 10/26/2020) MAP/LOT OWNER ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE PROP LOCATION I01/ 1/ / / LEAVITT, DONALD M & PAINE, TODD S 828 PARK AV BALTIMORE MD 21201 55 PINE ISLAND I01/ 1/A / / YOUNG, PAUL F TRUST; YOUNG, RUTH C TRUST 14 MITCHELL LN HANOVER NH 03755 54 PINE ISLAND I01/ 2/ / / YOUNG, PAUL F TRUST; YOUNG, RUTH C TRUST 14 MITCHELL LN HANOVER NH 03755 51 PINE ISLAND I01/ 3/ / / YOUNG, CHARLES FAMILY TRUST 401 STATE ST UNIT M501 PORTSMOUTH NH 03801 49 PINE ISLAND I01/ 4/ / / SALZMAN FAMILY REALTY TRUST 45-B GREEN ST JAMAICA PLAIN MA 02130 46 PINE ISLAND I01/ 5/ / / STONE FAMILY TRUST 36 VILLAGE RD APT 506 MIDDLETON MA 01949 43 PINE ISLAND I01/ 6/ / / VASSOS, DOUGLAS K & HOPE-CONSTANCE 220 LOWELL RD WELLESLEY HILLS MA 02481-2609 41 PINE ISLAND I01/ 6/A / / VASSOS, DOUGLAS K & HOPE-CONSTANCE 220 LOWELL RD WELLESLEY HILLS MA 02481-2609 PINE ISLAND I01/ 6/B / / KERNER, GERALD 317 W 77TH ST NEW YORK NY 10024-6860 38 PINE ISLAND I01/ 7/ / / KERNER, LOUISE G 317 W 77TH ST NEW YORK NY 10024-6860 36 PINE ISLAND I01/ 8/A / / 2012 PINE ISLAND TRUST C/O CLK FINANCIAL INC COHASSET MA 02025 23 PINE ISLAND I01/ 8/B / / MCCUNE, STEVEN; MCCUNE, HENRY CRANE; 5 EMERY RD SALEM NH 03079 26 PINE ISLAND I01/ 8/C / / MCCUNE, STEVEN; MCCUNE, HENRY CRANE; 5 EMERY RD SALEM NH 03079 33 PINE ISLAND I01/ 9/ / / 2012 PINE ISLAND TRUST C/O CLK FINANCIAL INC COHASSET MA 02025 21 PINE ISLAND I01/ 9/A / / 2012 PINE ISLAND TRUST C/O CLK FINANCIAL INC COHASSET MA 02025 17 PINE ISLAND I01/ 9/B / / FLYNN, MICHAEL P & LOUISE E 16 PINE ISLAND MEREDITH NH -

George Dorin - Survivor George Dorin Was Born July 14, 1936, in Paris, France

1 Coppel Speakers Bureau George Dorin - Survivor George Dorin was born July 14, 1936, in Paris, France. His life would forever change when the Nazis invaded France in 1940. After George’s father, Max Eli Zlotogorski, was taken by the Nazis, his mother, Regina, made the difficult decision to place George and his sister, Paulette, in hiding separately. George’s father was sent to Pithiviers internment camp between 1941 and 1942, then to Auschwitz, where he was murdered. His mother was first taken to Drancy and then to Auschwitz, where she was murdered. Paulette was hidden by various families while George was sent to live on a farm with the Chemin family. Passing as the child of Maria and Louis Chemin, George helped on the farm with their children, Louie Jr. and Denise. When the Nazis advanced near the farm, George was temporarily hidden by a priest in a nearby nunnery until it was safe to return to the Chemin home. In 1947, George was temporarily reunited with his sister before they were adopted by different families. Although separated after the war, George kept in touch with the Chemin family throughout his adult life. In 1948, George immigrated to the United States where he was adopted by Francis and Harry Dorin of New York. He entered the United States Airforce in 1954 and was trained as a medical technician. After his military service, George settled in Ohio where he opened Gedico International Inc., a successful printing company. George met his wife, Marion, in 1990, and together the couple has five children. -

Performing the Self on Survivor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M Repository TEMPORARILY MACHIAVELLIAN: PERFORMING THE SELF ON SURVIVOR An Undergraduate Research Scholars Thesis by REBECCA J. ROBERTS Submitted to the Undergraduate Research Scholars program at Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the designation as an UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH SCHOLAR Approved by Research Advisor: Dr. James Ball III May 2018 Major: Performance Studies Psychology TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................. 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................ 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTERS I. OUTWIT. OUTPLAY. OUTLAST ......................................................................... 8 History of Survivor ............................................................................................ 8 Origin Story of Survivor .................................................................................. 10 Becoming the Sole Survivor ............................................................................ 12 II. IDENTITY & SELF-PRESENTATION ................................................................ 17 Role Performance ........................................................................................... -

Chapter 53: Survivor Benefit Plan (SBP)

DoD Financial Management Regulation Volume 7B, Chapter 53 + June 2004 SUMMARY OF MAJOR CHANGES TO DOD 7000.14-R, VOLUME 7B, CHAPTER 53 "SURVIVOR BENEFIT PLAN (SBP) - TAXABILITY OF ANNUITIES" Substantive revisions are denoted by a + preceding the section, paragraph, table or figure that includes the revision. PARA EXPLANATION OF CHANGE/REVISION EFFECTIVE DATE 5301, Interim change R01-01 incorporates the taxability January 17, 2001 Table 53-2, of SBP cost refund. Bibliography Table 53-1 Interim change R09-02 excluded SBP annuities July 17, 2002 from federal taxation for Spanish nationals residing in Spain. Table 53-1 Interim change R13-02 updates Table 53-1 to October 24, 2002 reflect no tax withholding for an annuitant who is a citizen and resident of the countries of New Zealand, Russia, and Kazakhstan. This change also adds no tax withholding for an annuitant who is a national and resident in the countries of China, Estonia, Hungary, India, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, Portugal, South Africa, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, and Venezuela. 53-1 DoD Financial Management Regulation Volume 7B, Chapter 53 + June 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS SURVIVOR BENEFIT PLAN (SBP) – TAXABILITY OF ANNUITIES +5301 Federal Income Tax 5302 Federal Income Tax Withholding (FITW) 5303 Income Exclusion 5304 Adjustment to Taxable Annuity 5305 Amount of Annuity Subject to Federal Estate Tax 5306 State Taxation 5307 Further Tax Information 53-2 DoD Financial Management Regulation Volume 7B, Chapter 53 + June 2004 CHAPTER 53 SURVIVOR BENEFIT PLAN (SBP) – TAXABILITY OF ANNUITIES +5301 FEDERAL INCOME TAX 530101. Taxability of SBP Annuity Payments. The SBP annuity payments are taxable for federal income tax purposes. -

Australian Survivor 2019 - the Season That Outwitted, Outplayed and Outlasted Them All

Media Release 18 September 2019 Australian Survivor 2019 - the season that outwitted, outplayed and outlasted them all The votes have been tallied and this season of Australian Survivor broke audience records across all platforms – television, online and social - outperforming 2018’s record breaking season. Alliances were broken in the game and outside of the game, these were records that were broken this season: Network 10 • National total average audience (including 7 day television and broadcast video on-demand (BVOD)): 1.14 million. UP six per cent year on year. A CBS Company • Capital city total average audience: 912,000. UP ten per cent year on year. • National television average audience: 1.06 million. UP four per cent year on year. • Capital city television average audience: 823,000. UP seven per cent year on year. • 10 Play (7 day BVOD) average audience: 82,000. UP 37 per cent year on year. Across social, it was the most talked about entertainment show during its run. Total social interactions on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter soared 144 per cent year on year to 1.14m interactions, according to Nielsen Social Content Ratings. Australian Survivor’s 10 Play companion show, The Jury Villa, which followed the journey of jury members after they are eliminated from the game, achieved an average BVOD audience of 52,000, UP 64 per cent year on year. In the important advertising demographics, Australian Survivor was a challenge beast and across its run was the #1 show in under 50s and all key demos (16 to 39s, 18 to 49s and 25 to 54s). -

Survivor Beneficiary Designation Form

Public Employees’ Retirement System of Nevada 693 W. Nye Lane, Carson City, NV 89703 • (775) 687-4200 • Fax: (775) 687-5131 5740 S. Eastern Ave., Suite 120, Las Vegas, NV 89119 • (702) 486-3900 • Fax: (702) 678-6934 Toll Free: (866) 473-7768 • www.nvpers.org • Email: [email protected] SURVIVOR BENEFICIARY DESIGNATION **THIS FORM SUPERSEDES ALL PRIOR BENEFICIARY DESIGNATIONS** Member Information Name Change Yes No If Yes, Former Name: ___________________________ Name:________________________________________Social Security Number:_____________________ Employer: _________________________ Address:_____________________________________________________________City, State, Zip:________________________________________ Home Phone: __________________ Work Phone:____________________Email: _________________________________Birth Date: ____________ Date:_____________________________ Family Beneficiary Information. A spouse or registered domestic partner is a member’s primary beneficiary under NRS 286.674 and may be eligible to receive a lifetime benefit in the event of the member’s death prior to retirement. If a monthly benefit is not available, the spouse or registered domestic partner may be eligible to receive a one-time lump-sum payment of any existing member contributions in the System. Children under age 18 may be eligible to receive a limited benefit. Name of Spouse or Registered Domestic Partner:__________________________Social Security Number:________________Birth Date:__________ List all unmarried children (biological or legally adopted) -

Republic of Palau Comprehensive Cancer Control Plan, 2007-2012

National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007 - 2012 R National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007-2011 To all Palauans, who make the Cancer Journey May their suffering return as skills and knowledge So that the people of Palau and all people can be Cancer Free! Special Thanks to The planning groups and their chairs whose energy, Interest and dedication in working together to develop the road map for cancer care in Palau. We also would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Grant # U55-CCU922043) National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau 2007-2011 October 15, 2006 Dear Colleagues, This is the National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau. The National Cancer Strategic Plan for Palau provides a road map for nation wide cancer prevention and control strategies from 2007 through to 2012. This plan is possible through support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA), the Ministry of Health (Palau) and OMUB (Community Advisory Group, Palau). This plan is a product of collaborative work between the Ministry of Health and the Palauan community in their common effort to create a strategic plan that can guide future activities in preventing and controlling cancers in Palau. The plan was designed to address prevention, early detection, treatment, palliative care strategies and survivorship support activities. The collaboration between the health sector and community ensures a strong commitment to its implementation and evaluation. The Republic of Palau trusts that you will find this publication to be a relevant and useful reference for information or for people seeking assistance in our common effort to reduce the burden of cancer in Palau. -

Seawalls in Samoa: a Look at Their Ne Vironmental, Social and Economic Implications Sawyer Lawson SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2011 Seawalls in Samoa: A Look at Their nE vironmental, Social and Economic Implications Sawyer Lawson SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Environmental Health and Protection Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Place and Environment Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Lawson, Sawyer, "Seawalls in Samoa: A Look at Their nE vironmental, Social and Economic Implications" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1058. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1058 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seawalls in Samoa: A Look at Their Environmental, Social and Economic Implications Sawyer Lawson Project Advisor: Espen Ronneberg Academic Director: Jackie Fa’asisila S.I.T. Samoa, Spring 2011 Abstract: This study concerns the environmental, economic and social implications of seawalls in Samoa. Information for this study was gathered using a combination of secondary sources and primary sources including interviews, surveys and participant observation. Given the cultural and economic importance of Samoa’s coastline and the fact that seawalls, which already occupy much of Samoa’s coast, are becoming more abundant, it is important to understand the implications of building them. The researcher found that partially due to climate change and sand mining, Samoa’s coastline has become increasingly threatened by erosion and coastal retreat. -

Evaluating Spoken Dialogue Processing for Time-Offset Interaction

Evaluating Spoken Dialogue Processing for Time-Offset Interaction David Traum Kallirroi Georgila Ron Artstein Anton Leuski The work depicted here was sponsored by the U.S. Army. Statements and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the United States Government, and no official endorsement should be inferred. Outline . What is Time-offset interaction & “New Dimensions in Testimony” . Data collection . System Architecture . System Evaluation . ASR . Classification . User Impact 2 The Big Idea: changing how we communicating through space and time . Space (can be 2-way, interactive) . Time (so far non-interactive, . Semaphore maybe periodic) . Telegraph . Writing on paper/stone/tablets . Radio/Telephone . Audio Recordings . Video Conference . Film . Virtual worlds (e.g., 2nd life) . Electronic media . 3D video conference . Time-offset Interaction . Mostly interactive 3 Science Fiction/Fantasy imaginings of Conversations with Historical People Star Trek: Savage Curtain Holodeck: Star Trek TNG: Descent Harry Potter Portraits Headmaster portraits are capable of interaction with the living world. The headmaster or headmistress is painted before they die. When the portrait is completed, it is kept in a cupboard in the castle, and the headmaster or headmistress can teach their Hawking: " Wrong again, Albert!.” portrait to act and behave Kirk:" I cannot conceive it like themselves. Additionally, possible that Abraham Lincoln they can impart specific could have actually been information and knowledge reincarnated. -

Narrative Pleasure and Uncertainty Due to Chance in Survivor

Mary Beth Haralovich Michael Trosset Department of Media Arts Department of Mathematics University of Arizona College of William and Mary 520 621-7800 757 221-2040 [email protected] [email protected] “Expect the Unexpected”: Narrative Pleasure and Uncertainty Due to Chance in Survivor In the wrap episode of Survivor’s fifth season (Survivor 5: Thailand), host Jeff Probst expressed wonder at the unpredictability of Survivor. Five people each managed to get through the game to be the sole survivor and win the million dollars, yet each winner was different from the others, in personality, in background, and in game strategy. Probst takes evident pleasure in the fact that even he cannot predict the outcomes of Survivor, as close to the action as he is. Probst advised viewers interested in improving their Survivor skills to become acquainted with mathematician John Nash’s theory of games. Probst’s evocation on national television of Nash’s game theory invites both fans and critics to apply mathematics to playing and analyzing Survivor.1 While a game-theoretic analysis of Survivor is the subject for another essay, this essay explores our understanding of narrative pleasure of Survivor through mathematical modes of inquiry. Such exploration assumes that there is something about Survivor that lends itself to mathematical analysis. That is the element of genuine, unscripted chance. It is the presence of chance and its almost irresistible invitation to try to predict outcomes that distinguishes the Survivor reality game hybrid. In The Pleasure of the Text, Roland Barthes explored how narrative whets our desire to know what happens next.2 In Survivor’s reality game, the pleasure of “what happens next” is not based on the cleverness of scriptwriters or the narrowly evident skills of the players. -

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION Congratulating Sophie Clarke Upon the Occasion of Capturing the Esteemed Title of Sole Survivor on Survivor: South Pacific

LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION congratulating Sophie Clarke upon the occasion of capturing the esteemed title of Sole Survivor on Survivor: South Pacific WHEREAS, It is the sense of this Legislative Body to recognize and pay tribute to those young people within the State of New York who, by achieving outstanding success in physical as well as mental competi- tions, have inspired and brought pride to both the State of New York and their community; and WHEREAS, Attendant to such concern, and in full accord with its long- standing traditions, this Legislative Body is justly proud to congratu- late Sophie Clarke upon the occasion of capturing the esteemed title of Sole Survivor on Survivor: South Pacific; and WHEREAS, Survivor: South Pacific, filmed in the vicinity of Upolu, Samoa, was the 23rd season of the American CBS competitive reality tele- vision series Survivor, which premiered on Wednesday, September 14, 2011, and aired the finale on Sunday, December 18, 2011; and WHEREAS, Sophie Clarke was named the winner in the final episode, defeating Benjamin "Coach" Wade and Albert Destrade in a 6-3-0 vote, walking away with the First Prize of $1 million; and WHEREAS, When speaking out about the show and how it changed her, she recalls it was very nerve-wracking at times; she believed she had her finger on the pulse of the game, attempting to figure out the other player's motives; and WHEREAS, A major part of the game centered on interpersonal relation- ships, alliances and deceit; one characteristic Sophie Clarke believes she has, which is being more -

Survivor Options Fact Sheet

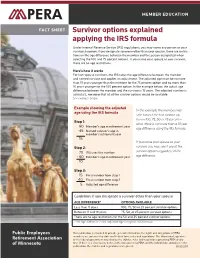

MEMBER EDUCATION FACT SHEET Survivor options explained applying the IRS formula Under Internal Revenue Service (IRS) regulations, you may name any person as your survivor; however, if you designate someone other than your spouse, there are restric- tions on the age difference between the member and the person designated when selecting the 100 and 75 percent options. If you name your spouse as your survivor, there are no age restrictions. Here’s how it works For non-spouse survivors, the IRS takes the age difference between the member and named survivor and applies an adjustment. The adjusted age must be no more than 19 years younger than the member for the 75 percent option and no more than 10 years younger for the 100 percent option. In the example below, the actual age difference between the member and the survivor is 15 years. The adjusted number is actually 5, meaning that all of the survivor options would be available. See example below. Example showing the adjusted In this example, the member may age using the IRS formula select any of the four survivor op- tions—100, 75, 50 or 25 percent— Step 1: since there is not more than a 10 year 60 Member’s age in retirement year age difference using the IRS formula. -45 Named survivor’s age in member’s retirement year 15 If you name your spouse as your Step 2: survivor, you may select any of the 70 IRS uses this number survivor options regardless of the - 60 Member’s age in retirement year age difference.