Arxiv:1009.4206V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Determining Pulsation Period for an RR Lyrae Star

Leah Fabrizio Dr. Mitchell 06/10/2010 Determining Pulsation Period for an RR Lyrae Star As children we used to sing in wonderment of the twinkling stars above and many of us asked, “Why do stars twinkle?” All stars twinkle because their emitted light travels through the Earth’s atmosphere of turbulent gas and clouds that move and shift causing the traversing light to fluctuate. This means that the actual light output of the star is not changing. However there are a number of stars called Variable Stars that actually produce light of varying brightness before it hits the Earth’s atmosphere. There are two categories of variable stars: the intrinsic, where light fluctuation is due from the star physically changing and producing different luminosities, and extrinsic, where the amount of starlight varies due to another star eclipsing or blocking the star’s light from reaching earth (AAVSO 2010). Within the category of intrinsic variable stars are the pulsating variables that have a periodic change in brightness due to the actual size and light production of the star changing; within this group are the RR Lyrae stars (“variable star” 2010). For my research project, I will observe an RR Lyrae and find the period of its luminosity pulsation. The first RR Lyrae star was named after its namesake star (Strobel 2004). It was first found while astronomers were studying the longer period variable stars Cepheids and stood out because of its short period. In comparison to Cepheids, RR Lyraes are smaller and therefore fainter with a shorter period as well as being much older. -

Searching for RR Lyrae Stars in M15

Searching for RR Lyrae Stars in M15 ARCC Scholar thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the ARCC Scholar program Khalid Kayal February 1, 2013 Abstract The expansion and contraction of an RR Lyrae star provides a high level of interest to research in astronomy because of the several intrinsic properties that can be studied. We did a systematic search for RR Lyrae stars in the globular cluster M15 using the Catalina Real-time Transient Survey (CRTS). The CRTS searches for rapidly moving Near Earth Objects and stationary optical transients. We created an algorithm to create a hexagonal tiling grid to search the area around a given sky coordinate. We recover light curve plots that are produced by the CRTS and, using the Lafler-Kinman search algorithm, we determine the period, which allows us to identify RR Lyrae stars. We report the results of this search. i Glossary of Abbreviations and Symbols CRTS Catalina Real-time Transient Survey RR A type of variable star M15 Messier 15 RA Right Ascension DEC Declination RF Radio frequency GC Globular cluster H-R Hertzsprung-Russell SDSS Sloan Digital Sky Survey CCD Couple-Charged Device Photcat DB Photometry Catalog Database FAP False Alarm Probability ii Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Background on RR Lyrae Stars 5 2.1 What are RR Lyraes? . 5 2.2 Types of RR Lyrae Stars . 6 2.3 Stellar Evolution . 8 2.4 Pulsating Mechanism . 9 3 Useful Tools and Surveys 10 3.1 Choosing M15 . 10 3.2 Catalina Real-time Transient Survey . 11 3.3 The Sloan Digital Sky Survey . -

Cepheid Variable Stars Cepheid Variable Stars As Distance Indicators

Cepheid Variable Stars Cepheid variable stars as distance indicators. Certain stars that have used up their main supply of hydrogen fuel are unstable and pulsate. RR Lyrae variables have periods of about a day. Their brightness doubles from dimest to brightest. Typical light curve for a Cepheid variable star. Cepheid variables have longer periods, from one day up to about 50 days. Their brightness also doubles from dimest to brightest. From the shape of the ``light curve'' of a Cepheid variable star, one can tell that it is a Cepheid variable. The period is simple to measure, as is the apparent brightness at maximum brightness. Cepheids as distance indicators Cepheids are important beyond their intrinsic interest as pulsating stars. Astronomomers have found that their is a relation between the period of a Cepheid and its luminosity. http://zebu.uoregon.edu/~soper/MilkyWay/cepheid.html (1 of 3) [5/25/1999 10:34:08 AM] Cepheid Variable Stars This enables astronomers to determine distances: ● Find the period. ● This gives the luminosity. ● Measure the apparent brightness. ● Determine the distance from the luminosity and brightness. The same applies to RR Lyrae variable stars. Once you know that a star is an RR Lyrae variable (eg. from the shape of its light curve), then you know its luminosity. Where did this period-luminosity relation come from? ● American astronomer Henrietta Leavitt looked at many Cepheid variables in the Small Magellanic Cloud (a satellite galaxy to ours.) ● She found the period luminosity relation (reported in 1912). ● One needs a distance measurement from some other method for at least one Cepheid. -

``But I Am Constant As the Northern Star of Whose True-Fixed and Resting Quality There Is No Fellow in the Firmament.'' William

``But I am constant as the Northern Star Of whose true-fixed and resting quality There is no fellow in the firmament.'' William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, 3, 1 Astronomy C - Variable Stars - 2008 A. Pulsating Variables: 1) Long Period Variables a) Mira type b) Semiregular 2) Cepheids 3) RR Lyrae B. Cataclysmic (Eruptive) Variables: 1) R Coronae Borealis 2) Flare Stars 3) Dwarf Novae 4) X-Ray Binaries 5) Supernovae a) Type II b) Type Ia C. Strangers in the Night Astronomy C - Variable Stars - 2008 A. Pulsating Variables: 1) Long Period Variables a) Mira type R Cygni b) Semiregular V725 SGR 2) Cepheids W Virginis 3) RR Lyrae AH Leo B. Cataclysmic (Eruptive) Variables: 1) R Coronae Borealis RY Sagittarii 2) Flare Stars UV Ceti 3) Dwarf Novae SU Ursae Majoris 4) X-Ray Binaries J1655-40, RX J0806.3+1527 5) Supernovae a) Type II G11.2-0.3, SN2006gy b) Type Ia DEM L71, Kepler’s SNR C. Strangers in the Night: V838 Mon Light Curves – Variation over Time Maximum (Maxima) Minimum (Minima) Period Apparent Magnitude vs Julian Day A. Pulsating Variable Stars; 1) Long Period Variables (LPVs) a) Miras 80 – 1000 days, 2.5 – 5.0 mag R Cygni b) Semiregular Variables 30 – 1000 days, 1.0 – 2.0 mag V725 Sgr Semiregular Mira Instability Strip 2) Cepheid Variable Stars W Virginis (Type 2) [Periods of .8 – 35 days, .3 – 1.2 mag] Type I and Type II Cepheid Variable Stars Type I (Classical) Cepheids: Young high-metallicity stars about 4 times more luminous than Type II Cepheids Type II Cepheids: Older low- metallicity stars about 4 times less luminous than classical Cepheids. -

RR Lyrae Stars and the Distance to the Center of the Galaxy

Activity 25: RR Lyrae Stars and the Distance to the Center of the Galaxy ©2014 W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 15 Post-25.1: What aspect about globular clusters and our observations of the distances to them modified our view of the Milky Way Galaxy and our place in it? a. They all orbit the center of the galaxy, and the center of their distribution is not where we are. b. Some of the globular clusters are very far away and must belong to the Andromeda Galaxy. c. We found out that there are hundreds of globular clusters hidden by columns of dust. d. The most distant globular clusters are metal-rich and so must have originated in the disk. ©2014 W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 16 Post-25.1: What aspect about globular clusters and our observations of the distances to them modified our view of the Milky Way Galaxy and our place in it? a. They all orbit the center of the galaxy, and the center of their distribution is not where we are. b. Some of the globular clusters are very far away and must belong to the Andromeda Galaxy. c. We found out that there are hundreds of globular clusters hidden by columns of dust. d. The most distant globular clusters are metal-rich and so must have originated in the disk. ©2014 W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 17 Post-25.2: Astronomers need to measure the distances to the stars in the Milky Way globular clusters. What method should they use to find the distances? a. -

Evolutionary Models of RR Lyrae Stars Young-Wook Lee Department of Astronomy, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

Evolutionary Models of RR Lyrae Stars Young-Wook Lee Department of Astronomy, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA 1. Introduction As tracers of old stellar populations and as primary Population II standard candles, RR Lyrae stars have played an important role in the development of modern astronomy. Our knowledge of stellar evolution has identified these variable stars in a core helium burning phase of low-mass star evolution, the hoiizontal-branch (HB) phase. Consequently, not only to understand fully the nature of RR Lyrae stars, but also to apply them correctly as population probes and distance indicators, we must understand the underlying evolution ary effect of HB stars. In this paper, I briefly review the most important properties of RR Lyrae stars pre dicted from the HB evolutionary models, and present many pieces of supporting evidence for these models. For the implications of these models on the chronology of the Galactic formation and on the cosmological distance scale, the reader is referred to several recent publications by Lee (1992a,b,c,d). 2. Properties of RR Lyrae Stars Predicted from HB Population Models The construction of HB population models is straightforward, once we have all the evolu tionary tracks for HB stars of different masses for a given composition. It is generally as sumed that the distribution of mass on the HB is Gaussian, resulting from variable amounts of mass-loss on the giant-branch. For each HB star, the time elapsed since the zero-age HB (ZAHB) is obtained by using a uniform random number generator. When the HB stars fall into the instability strip, we treat them as RR Lyrae variables. -

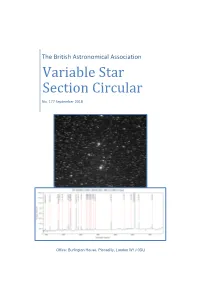

Variable Star Section Circular

The British Astronomical Association Variable Star Section Circular No. 177 September 2018 Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0DU Contents Observers Workshop – Variable Stars, Photometry and Spectroscopy 3 From the Director 4 CV&E News – Gary Poyner 6 AC Herculis – Shaun Albrighton 8 R CrB in 2018 – the longest fully substantiated fade – John Toone 10 KIC 9832227, a potential Luminous Red Nova in 2022 – David Boyd 11 KK Per, an irregular variable hiding a secret - Geoff Chaplin 13 Joint BAA/AAVSO meeting on Variable Stars – Andy Wilson 15 A Zooniverse project to classify periodic variable stars from SuperWASP - Andrew Norton 30 Eclipsing Binary News – Des Loughney 34 Autumn Eclipsing Binaries – Christopher Lloyd 36 Items on offer from Melvyn Taylor’s library – Alex Pratt 44 Section Publications 45 Contributing to the VSSC 45 Section Officers 46 Cover images Vend47 or ASASSN-V J195442.95+172212.6 2018 August 14.294, iTel 0.62m Planewave CDK @ f6.5 + FLI PL09--- CCD. 60 secs lum. Martin Mobberley Spectrum taken with a LISA spectroscope on Aug 16.875UT. C-11. Total exposure 1.1hr David Boyd Click on images to see in larger scale 2 Back to contents Observers' Workshop - Variable Stars, Photometry and Spectroscopy. Venue: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0DU (click to see map) Date: Saturday, 2018, September 29 - 10:00 to 17:30 For information about booking for this meeting, click here. A workshop to help you get the best from observing the stars, be it visually, with a CCD or DSLR or by using a spectroscope. The topics covered will include: • Visual observing with binoculars or a telescope • DSLR and CCD observing • What you can learn from spectroscopy And amongst those topics the types of star covered will include, CV and Eruptive Stars, Pulsating Stars and Eclipsing Binaries. -

Stellar Pulsation Meeting Program with Timeline Monday, June 1

Stellar Pulsation Meeting Program with Timeline Monday, June 1 Schedule 8:00-8:45 Put up posters 8:45-9:00 Welcome Session I. Cepheids and the Distance Scale Chair: W. Gieren 9:00-9:30 Thomas Barnes, Cepheid Distance Scale (Invited) 9:30-9:45 Wolfgang Gieren, A direct distance to the LMC from Cepheid variables 9:45-10:00 Giuseppe Bono, The Cepheid period-luminosity relation and the extragalactic distance scale 10:00-10:15 Lucas Macri, The SH0ES project: HST observations of Cepheids in NGC 4258 and type Ia SN hosts and implications for the Hubble Constant 10:15-10:45 Coffee break and Poster viewing 10:45-11:00 Nicolas Nardetto, From the dynamics of Cepheids to the Milky Way rotation, and the distance scale calibration 11:00-11:15 Shashi Kanbur, Multiphase PC/PL relations: Comparison between theory and observations Session II. Cepheid Theory and Observations Chair: Stephen Becker 11:15-11:45 J. Robert Buchler, Cepheid Pulsation Theory (Invited) 11:45-noon Victoria Scowcroft, The effect of metallicity on Cepheid magnitudes and the distance to M33 Noon-1:15 Lunch 1:15-1:45 David Turner, Polaris and its Kin (Invited) 1:45-2:00 Nancy Evans, Fundamental Parameters of Cepheids: Masses and Multiplicity 2:00-2:15 Radek Smolec, On resonant and non-resonant origin of double-mode Cepheid pulsation 2:15-2:30 Antoine Merand, What we learned from interferometric observations of Cepheids 2:30-2:45 Igor Soszynski, OGLE Data (short invited talk) 2:45-3:00 Edward Schmidt, Mining sky surveys for astrophysically interesting variable stars: The Cepheid period range 3:00-3:30 Coffee Break and Poster Viewing Session III. -

Gaia Data Release 2 Special Issue

A&A 620, A127 (2018) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833514 & © ESO 2018 Astrophysics Gaia Data Release 2 Special issue Gaia Data Release 2 Validating the classification of RR Lyrae and Cepheid variables with the Kepler and K2 missions? László Molnár1,2, Emese Plachy1,2, Áron L. Juhász1,3, and Lorenzo Rimoldini4 1 Konkoly Observatory, MTA CSFK, 1121, Budapest, Konkoly Thege Miklós út 15-17, Hungary 2 MTA CSFK Lendület Near-Field Cosmology Research Group, 1121, Budapest, Konkoly Thege Miklós út 15-17, Hungary e-mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Astronomy, Eötvös Loránd University, 1117, Budapest, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/a, Hungary 4 Department of Astronomy, University of Geneva, Chemin d’Ecogia 16, 1290, Versoix, Switzerland Received 28 May 2018 / Accepted 22 October 2018 ABSTRACT Context. The second data release of the Gaia mission (DR2) includes an advance catalogue of variable stars. The classifications of these stars are based on sparse photometry from the first 22 months of the mission. Aims. We set out to investigate the purity and completeness of the all-sky Gaia classification results with the help of the continuous light curves of the observed targets from the Kepler and K2 missions, focusing specifically on RR Lyrae and Cepheid pulsators, outside the Galactic bulge region. Methods. We cross-matched the Gaia identifications with the observations collected by the Kepler space telescope. We inspected the light curves visually, then calculated the relative Fourier coefficients and period ratios for the single- and double-mode K2 RR Lyrae stars to further classify them. -

Near-Ultraviolet Detections of Four Dwarf Nova Candidates in the Globular Cluster 47 Tucanae

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Near-ultraviolet detections of four dwarf nova candidates in the globular cluster 47 Tucanae Modiano, D.; Parikh, A.S.; Wijnands, R. DOI 10.1051/0004-6361/201937043 Publication date 2020 Document Version Final published version Published in Astronomy & Astrophysics Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Modiano, D., Parikh, A. S., & Wijnands, R. (2020). Near-ultraviolet detections of four dwarf nova candidates in the globular cluster 47 Tucanae. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 634, [A132]. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201937043 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep 2021 A&A 634, A132 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201937043 & c ESO 2020 Astrophysics Near-ultraviolet detections of four dwarf nova candidates in the globular cluster 47 Tucanae David Modiano, Aastha S. -

Identification and Characterization of Long Period Variable Stars in the Globular Cluster M69

IDENTIFICATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF LONG PERIOD VARIABLE STARS IN THE GLOBULAR CLUSTER M69 Paul W. Husband Jr. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2017 Committee: Andrew C. Layden, Advisor John B. Laird Dale W. Smith ii ABSTRACT Andrew Layden, Advisor Observations of the globular cluster M69 were taken from August 2009 to September 2014 using the 0.4-m PROMPT #4 telescope in Chile. This telescope took observations in V and I bandpass filters, approximately once per week, for ten months of each year. Using the image subtraction software suite ISIS, the cluster was examined for variable stars with an emphasis on long period variable stars. As a part of the overall project the long period variable stars were examined for multiple period relationships, including long secondary periods. The long period variables stars were also plotted in a color magnitude diagram, along with the rest of the stars in the images, to help evaluate the location of the long period variable stars on the diagram. Plots of period vs. I magnitude, period vs. I magnitude range, and I magnitude range vs I magnitude were also plotted to assess whether measurements of one or two characteristics would provide insight into other characteristics of the long period variable stars. The light curves, period examination, and tools to conduct them, are presented in the body of this paper. Having 400+ images in V and I filters over a 5-year time frame is an improvement over the previous work on M69, which was either photographic or photoelectric. -

Near-Ultraviolet Detections of Four Dwarf Nova Candidates in the Globular Cluster 47 Tucanae David Modiano, Aastha S

A&A 634, A132 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201937043 & c ESO 2020 Astrophysics Near-ultraviolet detections of four dwarf nova candidates in the globular cluster 47 Tucanae David Modiano, Aastha S. Parikh, and Rudy Wijnands Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy, University of Amsterdam, Postbus 94249, 1090 GE Amsterdam, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] Received 2 November 2019 / Accepted 15 December 2019 ABSTRACT We investigate near-ultraviolet variability in the Galactic globular cluster (GC) 47 Tucanae (47 Tuc). This work was undertaken within the GC sub-project of the Transient UV Objects project, a programme which aims to find and study transient and strongly variable UV sources. Globular clusters are ideal targets for transient searches because of their high stellar densities and large populations of variable systems. Using all 75 archival observations of 47 Tuc obtained with the UV/optical telescope (UVOT) aboard the Neil Gehrels Swift observatory with the uvm2 filter, we searched for UV variability using a specialised pipeline which utilises difference image analysis. We found four clear transients, hereafter SW1–4, with positions consistent with those of known cataclysmic variables (CVs) or CV candidates identified previously using Hubble Space Telescope observations. All four sources exhibit significant outbursts, likely brightening by several orders of magnitude. Based on the inferred outburst properties and the association with known CVs, we tentatively identify the UV transients as CV-dwarf novae (DNe). Two DNe have been previously observed in 47 Tuc: V2, which has a position consistent with that of SW4; and AKO 9, which was not in outburst during any of the UVOT observations.