Spry1 and Spry2 Are Essential for Development of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sprouty2 Deficiency in Mice Leads to the Development of Achalasia Benjamin Lee Staal Grand Valley State University

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Masters Theses Graduate Research and Creative Practice 12-2011 Sprouty2 Deficiency in Mice Leads to the Development of Achalasia Benjamin Lee Staal Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Staal, Benjamin Lee, "Sprouty2 Deficiency in Mice Leads to the Development of Achalasia" (2011). Masters Theses. 11. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/11 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPROUTY2 DEFICIENCY IN MICE LEADS TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF ACHALASIA Benjamin Lee Staal A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of GRAND VALLEY STATE UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Cell and Molecular Biology December 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I thank God for the privilege of studying His handiwork. I also wish to thank the members of my Graduate Committee for their support and guidance throughout this project. Finally, I thank my family, friends, and colleagues for their continual motivation. iii ABSTRACT SPROUTY2 DEFICIENCY IN MICE LEADS TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF ACHALASIA Sprouty 2 (Spry2), one of the four mammalian Spry family members, is a negative feedback regulator of many receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) signaling including Met. It fine-tunes RTKs signaling through multiple levels of regulations starting from RTK itself to several downstream molecules that are crucial for signal transduction. -

Sprouty2 Drives Drug Resistance and Proliferation in Glioblastoma Alice M

Published OnlineFirst May 1, 2015; DOI: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0183-T Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressors Molecular Cancer Research Sprouty2 Drives Drug Resistance and Proliferation in Glioblastoma Alice M. Walsh1, Gurpreet S. Kapoor2, Janine M. Buonato3, Lijoy K. Mathew4,5,Yingtao Bi6, Ramana V. Davuluri6, Maria Martinez-Lage7, M. Celeste Simon4,5, Donald M. O'Rourke2,7, and Matthew J. Lazzara3,1 Abstract Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is notoriously resistant to demonstrated that SPRY2 protein is definitively expressed in therapy, and the development of a durable cure will require the GBM tissue, that SPRY2 expression is elevated in GBM tumors identification of broadly relevant regulators of GBM cell tumor- expressing EGFR variant III (EGFRvIII), and that elevated igenicity and survival. Here, we identify Sprouty2 (SPRY2), a SPRY2 mRNA expression portends reduced GBM patient sur- known regulator of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK), as one such vival. Overall, these results identify SPRY2 and the pathways regulator. SPRY2 knockdown reduced proliferation and anchor- it regulates as novel candidate biomarkers and therapeutic age-independent growth in GBM cells and slowed xenograft targets in GBM. tumor growth in mice. SPRY2 knockdown also promoted cell death in response to coinhibition of the epidermal growth factor Implications: SPRY2, counter to its roles in other cancer settings, receptor (EGFR) and the c-MET receptor in GBM cells, an effect promotes glioma cell and tumor growth and cellular resistance to that involved regulation of the ability of the p38 mitogen-acti- targeted inhibitors of oncogenic RTKs, thus making SPRY2 and vated protein kinase (MAPK) to drive cell death in response to the cell signaling processes it regulates potential novel therapeutic inhibitors. -

Spry2 Regulates Signalling Dynamics and Terminal Bud Branching Behaviour During Lung Development

Genet. Res., Camb. (2015), vol. 97, e5. © Cambridge University Press 2015 1 doi:10.1017/S0016672315000026 Spry2 regulates signalling dynamics and terminal bud branching behaviour during lung development 1,2 2 YINGYING ZHAO AND TIMOTHY P. O’BRIEN * 1Shenzhen University Diabetes Center, AstraZeneca-Shenzhen University Joint Institute of Nephrology, Department of Physiology, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen 518060, China 2Department of Biomedical Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA (Received 7 November 2014; revised 12 January 2015; accepted 3 February 2015) Summary Development of mammalian lung involves reiterative outgrowth and branching of an epithelial tube into the surrounding mesenchymal bed. Each coordinated growth and branching cycle is driven by reciprocal signal- ling between epithelial and adjacent mesenchymal cells. This signalling network includes FGF, SHH, BMP4 and other pathways. We have characterized lung defects in 36Pub mice carrying a deletion that removes an antagonist of FGF signalling, Spry2. Spry2 deficient mice show an enlarged cystic structure located in the ter- minus of each lobes. Our study shows that Spry2 deficient lungs have reduced lung branching and the cystic structure forms in the early lung development stage. Furthermore, mice carrying a targeted disruption of Spry2 fail to complement the lung phenotype characterized in 36Pub mice. A Spry2-BAC transgene rescues the defect. Interestingly, cystic structure growth is accompanied by the reduced and spatially disorganized ex- pression of Fgf10 and elevated expression of Shh and Bmp4. Altered signalling balance due to the loss of Spry2 causes a delayed branch cycle and cystic growth. Our data underscores the importance of restricting cellular responsiveness to signalling and highlights the interplay between morphogenesis events and spatial localization of gene expression. -

Sprouty Proteins, Masterminds of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Angiogenesis (2008) 11:53–62 DOI 10.1007/s10456-008-9089-1 ORIGINAL PAPER Sprouty proteins, masterminds of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling Miguel A. Cabrita Æ Gerhard Christofori Received: 14 December 2007 / Accepted: 7 January 2008 / Published online: 25 January 2008 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2008 Abstract Angiogenesis relies on endothelial cells prop- Abbreviations erly processing signals from growth factors provided in Ang Angiopoietin both an autocrine and a paracrine manner. These mitogens c-Cbl Cellular homologue of Casitas B-lineage bind to their cognate receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) on lymphoma proto-oncogene product the cell surface, thereby activating a myriad of complex EGF Epidermal growth factor intracellular signaling pathways whose outputs include cell EGFR EGF receptor growth, migration, and morphogenesis. Understanding how eNOS Endothelial nitric oxide synthase these cascades are precisely controlled will provide insight ERK Extracellular signal-regulated kinase into physiological and pathological angiogenesis. The FGF Fibroblast growth factor Sprouty (Spry) family of proteins is a highly conserved FGFR FGF receptor group of negative feedback loop modulators of growth GDNF Glial-derived neurotrophic factor factor-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Grb2 Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 activation originally described in Drosophila. There are HMVEC Human microvascular endothelial cell four mammalian orthologs (Spry1-4) whose modulation of Hrs Hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine RTK-induced signaling pathways is growth factor – and kinase substrate cell context – dependant. Endothelial cells are a group of HUVEC Human umbilical vein endothelial cell highly differentiated cell types necessary for defining the MAPK Mitogen-activated protein kinase mammalian vasculature. -

T Cell Depending on the Differentiation State of the Dual

Dual Effects of Sprouty1 on TCR Signaling Depending on the Differentiation State of the T Cell This information is current as Heonsik Choi, Sung-Yup Cho, Ronald H. Schwartz and of September 29, 2021. Kyungho Choi J Immunol 2006; 176:6034-6045; ; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6034 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/176/10/6034 Downloaded from References This article cites 63 articles, 29 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/176/10/6034.full#ref-list-1 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication by guest on September 29, 2021 *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2006 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology Dual Effects of Sprouty1 on TCR Signaling Depending on the Differentiation State of the T Cell1 Heonsik Choi,* Sung-Yup Cho,† Ronald H. Schwartz,* and Kyungho Choi2* Sprouty (Spry) is known to be a negative feedback inhibitor of growth factor receptor signaling through inhibition of the Ras/ MAPK pathway. -

Thesis Resubmission Daphne Chen

Integrative Modelling of Glucocorticoid Induced Apoptosis with a Systems Biology Approach A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Life Sciences 2012 Daphne Wei-Chen Chen 1 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................... 7 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................ 11 List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. 12 Abstract ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Short Abstract ............................................................................................................................. 15 Declaration ................................................................................................................................... 15 Copyright Statement ................................................................................................................... 15 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... 16 1 CHAPTER 1: Introduction .......................................................................................... 17 1.1 Glucocorticoids (GCs) ................................................................................................. -

Down-Regulation of Sprouty2 in Non–Small Cell Lung

Down-Regulation of Sprouty2 in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Contributes to Tumor Malignancy via Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Pathway- Dependent and -Independent Mechanisms Hedwig Sutterlu¨ty,1 Christoph-Erik Mayer,1 Ulrike Setinek,2 Johannes Attems,2 Slav Ovtcharov,1 Mario Mikula,1 Wolfgang Mikulits,1 Michael Micksche,1 and Walter Berger1 1Institute of Cancer Research, Department of Medicine I, Medical University Vienna and 2Institute for Pathology and Bacteriology, Otto Wagner Hospital Baumgartner Ho¨he, Vienna, Austria Abstract Introduction Sprouty (Spry) proteins function as inhibitors of Lung cancer is the leading cancer-related death in the receptor tyrosine kinase signaling mainly by interfering industrial world. Lung tumors are classified in small cell and with the Ras/Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase non–small cell lung cancer (SCLC and NSCLC), the latter cascade, a pathway known to be frequently deregulated representing over 75%of all lung tumors. NSCLC are further in human non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In this subdivided into squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarci- study, we show a consistently lowered Spry2 expression noma, and large cell carcinoma (LCC). All types of lung tumors in NSCLC when compared with the corresponding are associated with poor prognosis, and further progress in normal lung epithelium. Based on these findings, treatment strategies is believed to be dependent on a more we investigated the influence of Spry2 expression on extensive knowledge on critical pathways involved in tumor the malignant phenotype of NSCLC cells. Ectopic development and progression (1). expression of Spry2 antagonized mitogen-activated One of the characteristics frequently linked to human cancer protein kinase activity and inhibited cell migration in cell is the deregulation of signal transduction via receptor tyrosine lines homozygous for K-Ras wild type, whereas in kinases (RTK). -

SPRY2 Is an Inhibitor of the Ras/Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Pathway in Melanocytes and Melanoma Cells with Wild-Type BRAF but Not with the V599E Mutant

[CANCER RESEARCH 64, 5556–5559, August 15, 2004] Advances in Brief SPRY2 Is an Inhibitor of the Ras/Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Pathway in Melanocytes and Melanoma Cells with Wild-Type BRAF but Not with the V599E Mutant Dimitra Tsavachidou,1 Mathew L. Coleman,1 Galene Athanasiadis,1 Shuixing Li,1 Jonathan D. Licht,2 Michael F. Olson,1 and Barbara L. Weber1 1Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and 2Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York Abstract initiation in the absence of a BRAF mutation. In the present study, we aimed to identify such factors that may act in a wild-type (WT) BRAF BRAF mutations result in constitutively active BRAF kinase activity context. Using high-throughput microarray screening, we identified and increased extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling and the inhibitor SPRY2 being under-expressed in WT BRAF melanoma cell proliferation. Initial studies have shown that BRAF mutations occur at a high frequency in melanocytic nevi and metastatic lesions, but recent cells. data have revealed much lower incidence of these mutations in early-stage Materials and Methods melanoma, implying that other factors may contribute to melanoma pathogenesis in a wild-type (WT) BRAF context. To identify such con- Cell Lines and Cell Culture. Normal melanocytes and primary melanoma tributing factors, we used microarray gene expression profiling to screen cell lines were obtained from M. Herlyn (Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA). for differences in gene expression between a panel of melanocytic and BRAF mutation status and tumor stage were determined previously (4).3 All melanoma cell lines with WT BRAF and a group of melanoma cell lines cell lines have WT NRAS (4).3 Human melanocytes and melanoma cells were with the V599E BRAF mutation. -

Termination of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signal

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review All Good Things Must End: Termination of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signal Azzurra Margiotta 1,2 1 Department of Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, 62500 Brno, Czech Republic; [email protected] 2 International Clinical Research Center, St. Anne’s University Hospital, 65691 Brno, Czech Republic Abstract: Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are membrane receptors that regulate many fundamental cellular processes. A tight regulation of RTK signaling is fundamental for development and survival, and an altered signaling by RTKs can cause cancer. RTKs are localized at the plasma membrane (PM) and the major regulatory mechanism of signaling of RTKs is their endocytosis and degradation. In fact, RTKs at the cell surface bind ligands with their extracellular domain, become active, and are rapidly internalized where the temporal extent of signaling, attenuation, and downregulation are modulated. However, other mechanisms of signal attenuation and termination are known. Indeed, inhibition of RTKs’ activity may occur through the modulation of the phosphorylation state of RTKs and the interaction with specific proteins, whereas antagonist ligands can inhibit the biological responses mediated by the receptor. Another mechanism concerns the expression of endogenous inactive receptor variants that are deficient in RTK activity and take part to inactive heterodimers or hetero-oligomers. The downregulation of RTK signals is fundamental for several cellular functions and the homeostasis of the cell. Here, we will review the mechanisms of signal attenuation and termination of RTKs, focusing on FGFRs. Keywords: RTKs; FGFRs; termination of signaling; degradation; ubiquitination; PTPs; kinases Citation: Margiotta, A. All Good Things Must End: Termination of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signal. -

Loss of the Mir-21 Allele Elevates the Expression of Its Target Genes and Reduces Tumorigenesis

Loss of the miR-21 allele elevates the expression of its target genes and reduces tumorigenesis Xiaodong Maa,1, Munish Kumarb,1, Saibyasachi N. Choudhurya, Lindsey E. Becker Buscagliaa, Juanita R. Barkera, Keerthy Kanakamedalaa, Mo-Fang Liuc, and Yong Lia,2 aDepartment of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, School of Medicine, University of Louisville, 319 Abraham Flexner Way, Louisville, KY, 40202; bDepartment of Biotechnology, Assam University (Central University), Silchar, Assam-788 011, India; and cState Key Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai 200031, China Edited* by Sidney Altman, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and approved May 2, 2011 (received for review March 8, 2011) MicroRNA 21 (miR-21) is overexpressed in virtually all types of Using in vitro assays, the oncogenic properties of miR-21 have carcinomas and various types of hematological malignancies. To been extensively studied with molecular and cellular assays in determine whether miR-21 promotes tumor development in vivo, various cell lines (11–15). Recently, two reports from the labora- we knocked out the miR-21 allele in mice. In response to the 7,12- tories of Slack (16) and Olson (17) revealed that overexpression dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)/12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol- of miR-21 leads to a pre-B malignant lymphoid-like phenotype 13-acetate mouse skin carcinogenesis protocol, miR-21-null mice (16) and enhances Kras-mediated lung tumorigenesis (17), showed a significant reduction in papilloma formation compared whereas genetic deletion of miR-21 partially protects against with wild-type mice. We revealed that cellular apoptosis was ele- tumorigenesis (17). -

The Bimodal Regulation of Epidermal Growth Factor Signaling by Human Sprouty Proteins

The bimodal regulation of epidermal growth factor signaling by human Sprouty proteins James E. Egan*, Amy B. Hall†, Bogdan A. Yatsula†, and Dafna Bar-Sagi†‡ †Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology and *Graduate Program in Molecular Pharmacology, State University of New York, Stony Brook, NY 11794-5222 Communicated by Joseph Schlessinger, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, March 6, 2002 (received for review July 22, 2001) Signal transduction through epidermal growth factor receptors inhibitory effects of dSpry on DER signaling, genetic and biochem- (EGFRs) is essential for the growth and development of multicellular ical studies have shown that it also negatively regulates Drosophila organisms. A genetic screen for regulators of EGFR signaling has led tracheal branching by interfering with Branchless fibroblast growth to the identification of Sprouty, a cell autonomous inhibitor of EGF factor (FGF) signaling (8). Although in the Drosophila tracheal signaling that is transcriptionally induced by the pathway. However, system dSpry acts non-cell-autonomously to repress FGF signaling the molecular mechanisms by which Sprouty exerts its antagonistic (8), in the Drosophila eye system, dSpry acts cell autonomously to effect remain largely unknown. Here we have used transient expres- antagonize EGFR signaling (4, 5). sion in human cells to investigate the functional properties of human The Drosophila Sprouty gene encodes a 63-kD membrane- Sprouty (hSpry) proteins. Ectopically expressed full-length hSpry1 associated protein with a unique carboxyl-terminal cysteine-rich and hSpry2 induce the potentiation of EGFR-mediated mitogen- domain that is highly conserved in the four vertebrate Sprouty activated protein (MAP) kinase activation. In contrast, truncation homologs (Spry1-4) (9, 10). -

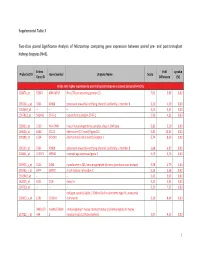

Supplemental Table 3 Two-Class Paired Significance Analysis of Microarrays Comparing Gene Expression Between Paired

Supplemental Table 3 Two‐class paired Significance Analysis of Microarrays comparing gene expression between paired pre‐ and post‐transplant kidneys biopsies (N=8). Entrez Fold q‐value Probe Set ID Gene Symbol Unigene Name Score Gene ID Difference (%) Probe sets higher expressed in post‐transplant biopsies in paired analysis (N=1871) 218870_at 55843 ARHGAP15 Rho GTPase activating protein 15 7,01 3,99 0,00 205304_s_at 3764 KCNJ8 potassium inwardly‐rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 8 6,30 4,50 0,00 1563649_at ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 6,24 3,51 0,00 1567913_at 541466 CT45‐1 cancer/testis antigen CT45‐1 5,90 4,21 0,00 203932_at 3109 HLA‐DMB major histocompatibility complex, class II, DM beta 5,83 3,20 0,00 204606_at 6366 CCL21 chemokine (C‐C motif) ligand 21 5,82 10,42 0,00 205898_at 1524 CX3CR1 chemokine (C‐X3‐C motif) receptor 1 5,74 8,50 0,00 205303_at 3764 KCNJ8 potassium inwardly‐rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 8 5,68 6,87 0,00 226841_at 219972 MPEG1 macrophage expressed gene 1 5,59 3,76 0,00 203923_s_at 1536 CYBB cytochrome b‐245, beta polypeptide (chronic granulomatous disease) 5,58 4,70 0,00 210135_s_at 6474 SHOX2 short stature homeobox 2 5,53 5,58 0,00 1562642_at ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 5,42 5,03 0,00 242605_at 1634 DCN decorin 5,23 3,92 0,00 228750_at ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 5,21 7,22 0,00 collagen, type III, alpha 1 (Ehlers‐Danlos syndrome type IV, autosomal 201852_x_at 1281 COL3A1 dominant) 5,10 8,46 0,00 3493///3 IGHA1///IGHA immunoglobulin heavy constant alpha 1///immunoglobulin heavy 217022_s_at 494 2 constant alpha 2 (A2m marker) 5,07 9,53 0,00 1 202311_s_at