The Use of Hyperbole in the Argumentation Stage" (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Dickens, 'Hard Times' and Hyperbole Transcript

Charles Dickens, 'Hard Times' and Hyperbole Transcript Date: Tuesday, 15 November 2016 - 6:00PM Location: Museum of London 15 November 2016 Charles Dickens: Hard Times and Hyperbole Professor Belinda Jack As I said in my last lecture, ‘Rhetoric’ has a bad name. Phrases like ‘empty rhetoric’, ‘it’s just rhetoric’ and the like suggest that the main purpose of rhetoric is to deceive. This, of course, can be true. But rhetoric is also an ancient discipline that tries to make sense of how we persuade. Now we could argue that all human communication sets out to persuade. Even a simple rhetorical question as clichéd and mundane as ‘isn’t it a lovely day?’ could be said to have a persuasive element. So this year I want to explore the nuts and bolts of rhetoric in relation to a number of famous works of literature. What I hope to show is that knowing the terms of rhetoric helps us to see how literature works, how it does its magic, while at the same time arguing that great works of literature take us beyond rhetoric. They push the boundaries and render the schema of rhetoric too rigid and too approximate. In my first lecture in the new series we considered Jane Austen’s novel entitled Persuasion (1817/1818) – what rhetoric is all about – in relation to irony and narrative technique, how the story is told. I concluded that these two features of Austen’s last completed novel functioned to introduce all manner of ambiguities leaving the reader in a position of uncertainty and left to make certain choices about how to understand the novel. -

All Or Nothing: a Semantic Analysis of Hyperbole

volumen 4 año 2009 ALL OR NOTHING: A SEMANTIC ANALYSIS OF HYPERBOLE Laura Cano Mora Universitat de València Abstract: This paper focuses on hyperbole, a long neglected form of non-literal language despite its pervasi- veness in everyday speech. It addresses the production process of exaggeration, since a crucial limitation in figurative language theories is the production and usage of figures of speech, probably due to the intensive research effort on their comprehension. The aim is to analyse hyperbole from a semantic perspective in order to devise a semasiological taxonomy which enables us to understand the nature and uses of the trope. In order to analyse and classify hyperbolic items a corpus of naturally occurring conversations extracted from the British National Corpus was examined. The results suggest that the evaluative and quantitative dimen- sions are key, defining features which often co-occur and should therefore be present in any definition of this figure of speech. A remarkable preference for negative affect, auxesis and absolute terms when engaging in hyperbole is also observed. Key words: figurative language, hyperbole, semantic field, corpus analysis “There is no one who does not exaggerate. In conversation, men are encumbered with personality and talk too much”. (Ralph Waldo Emerson) 1. INTRODUCTION TO NON-LITERAL LANGUAGE Since antiquity figures of speech have been widely studied within rhetoric, although in con- temporary rhetoric their study has been neglected or relegated to literary criticism. However, since the 1980s, there has been a renewed interest in figurative language not only in literary studies, but also in other fields of research. -

![Multimodal Hyperbole[Final]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9060/multimodal-hyperbole-final-3549060.webp)

Multimodal Hyperbole[Final]

Multimodal Hyperbole Gaëlle Ferré To cite this version: Gaëlle Ferré. Multimodal Hyperbole. Multimodal Communication, De Gruyter Mouton, 2014, 3 (1), pp.25-50. 10.1515/mc-2014-0003. hal-01422552 HAL Id: hal-01422552 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01422552 Submitted on 26 Dec 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Multimodal Hyperbole Gaëlle Ferré LLING, Université de Nantes Chemin de la Censive du Tertre BP 81227, 44312 Nantes cedex 3, France [email protected] Abstract This paper presents a study of hyperbole in the framework of Multimodal Discourse Analysis, based on video recordings of conversational English. Hyperbole is a figure of speech used to express exaggerated statements which do not correspond to reality but which are nevertheless not perceived as lies. Hyperbole opens up a discourse frame and establishes a new focus on information in speech making that piece of information more salient than surrounding discourse. The emphasis thus created thanks to various semantic-syntactic processes is reflected in prosody and gesture with the use of focalization devices. At last, prosodic patterns and gestures do not only reinforce verbal emphasis, they may fully contribute to the emphasis in a complementary way, and even constitute hyperbolic communicative acts by themselves. -

The Use of Hyperbole in the Argumentation Stage

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The use of hyperbole in the argumentation stage Snoeck Henkemans, A.F. Publication date 2013 Document Version Final published version Published in Virtues of argumentation: proceedings of the 10th International Conference of the Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation (OSSA), 22-26 May 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Snoeck Henkemans, A. F. (2013). The use of hyperbole in the argumentation stage. In D. Mohammed, & M. Lewiński (Eds.), Virtues of argumentation: proceedings of the 10th International Conference of the Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation (OSSA), 22-26 May 2013 OSSA. http://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA10/papersandcommentaries/159/ General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 The use of hyperbole in the argumentation stage A. -

Select Stylistic Devices, Literary Devices and Figures of Speech

Select Stylistic Devices, Literary Devices and Figures of Speech Urban 1 stylistic device = tool or technique that offers extra meaning, idea or feeling literary device = disruptive stylistic device - forces reader to reconsider, reread and respond emotionally to what read figure of speech = implied literary device - forces reader to realize implied, alternate (figurative) meanings in writing use to - personalize, deepen and broaden meaning - emphasize ideas writer wants reader to notice List of Devices and Figures Pheme = word or phrase Lexis = word meaning Statement = stich or clause Semantics = sentence meaning Passage = distinct section of a composition Pragmatics = contextual meaning Composition = poem or prose Intertextual features = series, sequence or other relation 0000s: idea and meaning Theme, Motif, Type, Idea, Meaning, Rhetoric, Elocution, Style, Voice, Stylistic Device, Diction, Syntax, Belles Lettres, Logopoeia, Melopoeia, Phanopoeia, Defamiliarization, Literary (Rhetorical) Device, Scheme, Figure of Speech (Trope), Figurative, Literal, Denotation, Connotation, Synonym, Antonym 0100s: transfer and twists Simile, Metaphor, Catachresis, Dead Metaphor, Extended Metaphor, Conceit, Allegory, Parable, Intertextuality, Synesthesia, Ambiguity, Contingency, Idiom, Innuendo, Irony, Verbal Irony, Socratic Irony, Dramatic Irony, Tragic Irony, Situational Irony, Sarcasm, Paradox, Oxymoron, Antiphrasis, Antistrophe, Interlacement, Pun, Polysemiac Pun, Metaphoric Pun, Paronomasia, Malapropism, Antanaclasis, Syllepsis, Zeugma, Spoonerism, -

An Exploratory Study of Personification and Hyperbole in Selected Siswati Poetry

IRA-International Journal of Education & QUARTERLY Multidisciplinary Studies ISSN 2455–2526; Vol.15, Issue 05 (Oct.—Dec. 2019) Pg. no. 160-166. Institute of Research Advances https://research-advances.org/index.php/IJEMS An Exploratory Study of Personification and Hyperbole in Selected Siswati Poetry Dr Jozi Joseph Thwala University of Mpumalanga Private Bag X11283 Mbombela South Africa 1200 Type of Work: Peer-Reviewed DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21013/jems.v15.n5.p1 How to cite this paper: Thwala, J.J. (2019). An Exploratory Study of Personification and Hyperbole in Selected Siswati Poetry. IRA International Journal of Education and Multidisciplinary Studies (ISSN 2455-2526), 15(5), 160-166. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.21013/jems.v15.n5.p1 © Institute of Research Advances. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License subject to a proper citation to the publication source of the work. Disclaimer: The scholarly papers as reviewed and published by the Institute of Research Advances (IRA) are the views and opinions of their respective authors and are not the views or opinions of the IRA. The IRA disclaims of any harm or loss caused due to the published content to any party. Institute of Research Advances is an institutional publisher member of Publishers International Linking Association Inc. (PILA-CrossRef), USA. The institute is an institutional signatory to the Budapest Open Access Initiative, Hungary advocating the open-access of scientific and scholarly knowledge. The Institute is a registered content provider under Open Access Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH). The journal is indexed & included in WorldCat Discovery Service (USA), CrossRef Metadata Search (USA), WorldCat (USA), OCLC (USA), Open J-Gate (India), EZB (Germany) Scilit (Switzerland), Airiti (China), Bielefeld Academic Search Engine (BASE) of Bielefeld University, Germany, PKP Index of Simon Fraser University, Canada. -

Linguistic Realization of Rhetorical Strategies in Barack Obama and Dalia Grybauskaitė’S Political Speeches

LITHUANIAN UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES FACULTY OF PHILOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PHILOLOGY INGRIDA STAUGAITĖ LINGUISTIC REALIZATION OF RHETORICAL STRATEGIES IN BARACK OBAMA AND DALIA GRYBAUSKAITĖ’S POLITICAL SPEECHES MA Paper Academic Advisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Linas Selmistraitis Vilnius, 2014 LIETUVOS EDUKOLOGIJOS UNIVERSITETAS FILOLOGIJOS FAKULTETAS ANGLŲ FILOLOGIJOS KATEDRA RETORINIŲ STRATEGIJŲ KALBINIS REALIZAVIMAS BARAKO OBAMOS IR DALIOS GRYBAUSKAITĖS POLITINĖSE KALBOSE Magistro darbas Humanitariniai mokslai, filologija (04H) Magistro darbo autorė Ingrida Staugaitė Patvirtinu, kad darbas atliktas savarankiškai, naudojant tik darbe nurodytus šaltinius _____________________________ (Parašas, data) Vadovas doc. dr. Linas Selmistraitis _____________________________ (Parašas, data) 2 CONTENT ABSTRACT 4 INTRODUCTION 5 1. THE ART OF RHETORIC 7 1.1 Rhetoric and communication 7 1.2 History of rhetoric 9 1.3 Rhetorical strategies 13 1.3.1 Argumentation 14 1.3.2 Persuasion 16 2. LINGUISTIC MANAGEMENT IN POLITICAL SPEECHES 17 2.1 Stylistic approach in political speeches 17 2.2 Functions and classification of stylistic devices 20 2.2.1 Metaphor 24 2.2.2 Epithet 27 2.2.3 Hyperbole 28 2.2.4 Rhetorical questions 29 3. BARACK OBAMA’S RHETORICAL STRATEGIES AND THEIR LINGUISTIC REALIZATION 30 3.1. Stylistic peculiarities of metaphors in the speeches 30 3.2. Stylistic peculiarities of epithets in the speeches 34 3.3. Stylistic peculiarities of hyperbole in the speeches 37 3.4. Stylistic peculiarities of rhetorical questions in the speeches 39 4. DALIA GRYBAUSKAITĖ’S RHETORICAL STRATEGIES AND THEIR LINGUISTIC REALIZATION 41 4.1. Stylistic peculiarities of metaphors in the speeches 41 4.2. Stylistic peculiarities of epithets in the speeches 46 4.3. Stylistic peculiarities of hyperbole in the speeches 49 4.4. -

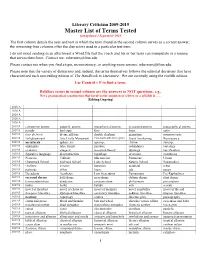

Master List of Terms Tested Last Updated 1 September 2019

Literary Criticism 2009-2019 Master List of Terms Tested last updated 1 September 2019 The first column details the year and test in which the term found in the second column serves as a correct answer; the remaining four columns offer the distractors used in a particular test item. I do not mind sending as an attachment a Word file that the coach and his or her team can manipulate in a manner that serves them best. Contact me: [email protected] Please contact me when you find a typo, inconsistency, or anything more serious: [email protected] Please note that the variety of distractors and, indeed, the terms themselves follows the editorial decisions that have characterized each succeeding edition of The Handbook to Literature. We are currently using the twelfth edition. Use Control + F to find a term. Boldface terms in second column are the answers to NOT questions; e.g., Not a grammatical construction that involves the omission of a litter or a syllable is . [Editing Ongoing] 2020 A 2020 A 2020 A 2020 A 2020 A 2019 S companion poems autotelic poems metaphysical poems occasional poems topographical poems 2019 S parody burlesque farce hoax satire 2019 S tour de force divine afflatus double elephant gigantism magnum opus 2019 S Enlightenment Arts Crafts Movement Commonwealth Interregnum Great Awakening Renaissance 2019 S metathesis aphaeresis apocope elision syncope 2019 S ambiguity false friend paradox redundancy tautology 2019 S scansion exegesis reception theory typology versification 2019 S figurative language deconstruction hypallage -

Download PDF Datastream

Disruptive Verse: Hyperbole and the Hyperbolic Persona in Ovid’s Exile Poetry By Rachel Severynse Philbrick B.A., Cornell University, 2007 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2016 © Copyright 2016 by Rachel S. Philbrick This dissertation by Rachel S. Philbrick is accepted in its present form by the Department of Classics as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date _____________________ ___________________________________ Joseph Reed, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date _____________________ ___________________________________ Johanna Hanink, Reader Date _____________________ ___________________________________ Pura Nieto Hernandez, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date _____________________ ___________________________________ Peter M. Weber, Dean of Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Rachel Severynse Philbrick was born on May 25, 1985, in Boston, Massachusetts. She grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with her parents and older sister, and attended high school at Commonwealth School in Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood. As an undergraduate, she attended Cornell University, graduating in 2007 with highest honors, having earned a B.A. in Latin and a B.A. in Biology and Society. Following graduation, she taught science at Kramer Middle School in Washington, D.C., before enrolling at the University of Kentucky in August 2009, where she earned a Master’s degree in Classics in 2011. That fall, she entered the doctoral program at Brown University in the Department of Classics. In the fall of 2016, he will join the Department of Classics at Georgetown University as a Visiting Assistant Professor. iv Acknowledgements It is no exaggeration to say that this dissertation would not have been possible without the support of countless people. -

A Pragmatic Analysis of Hyperbole in John Keats‟ Love Letters to Fanny Brawn

Journal for the Study of English Linguistics ISSN 2329-7034 2016, Vol. 4, No. 1 A Pragmatic Analysis of Hyperbole in John Keats‟ Love Letters to Fanny Brawn Dr. Sahar Altikriti Department of English, Faculty of Arts, Alzaytoonah University of Jordan, Jordan P.O. Box 130, Amman, 11733, Jordan Tel: 962-6-429-1511 E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 20, 2016 Accepted: August 8, 2016 Published: August x, 2016 doi:10.5296/jsel.v4i1.9885 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5296/jsel.v4i1.9885 Abstract Hyperbole is an ever-present figure of speech in daily communication. It over-exaggerates the speaker‟s meaning through his / her intense feelings and sincere attitude towards the listener, and hence, it reflects the speaker‟s real intention. Hyperbole received a scant attention in comparison to other figures of speech as linguistic and discourse studies attempted to focus on the listener‟s response rather than considering the interactive aspect. Hyperbolic expressions have been discussed in informal everyday conversation and academic writing, but less in other genres such as the genre of love letters. Moreover, a pragmatic analysis to both notions has not been shed light upon with much consideration. Thus, the main aim of this study is to investigate both the pragmatic role of hyperbole and detect the use of politeness strategies in seven love letters written by John Keats addressed to Fanny Brawne. The analysis is based on the recognition of positive and negative politeness strategies proposed in Brown and Levinson‟s Theory of Politeness (1987).The study demonstrates that both positive and negative strategies and the pragmatic function of hyperbole correlate with the writer‟s status and vary according to the context of situation. -

An Analysis of Figurative Language | 9

Abdullah & Ugi Rahayu: An Analysis of Figurative Language | 9 AN ANALYSIS OF FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE IN AVRIL LAVIGNE SONGS IN ALBUM AVRIL LAVIGNE. Abdullah1, Ugi Rahayu Rahmawati2 STIBA – IEC Bekasi. [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT This research aims to know and understanding the element of literature, especially in figurative language. The objectives of this research are (1). To identify some elements of figurative language are used by Avril Lavigne’s songs lyric. (2). To show the general meaning and detail meaning of the songs containing the figurative language itself in understanding songs lyric. (3). To find out the most and the least used figurative language of the songs. The data source used is the album self-titled Avril Lavigne by Avril Lavigne. In that album the writer chooses five songs to analyzed such as, Here’s to Never Growing Up, Bitchin’ Summer, Give You, What You Like, Hello Kitty, and Sippin’ on Sunshine. This research is descriptive qualitative research. It means that this research does not calculate the data and just gives description about figurative language that is contained in Avril Lavigne songs. It is done by using bold and underlining the songs lyric, classifying the figurative language and then giving the meaning. The result of this research is to discover some kinds of figurative language such as, Metaphor, Simile, Personification, Alliteration, Allusion, Hyperbole, Litotes, also Onomatopoeia. Keywords : Literature, Figurative Language, Qualitative descriptive analysis. A. INTRODUCTION 1. Background Figurative language is language using figure of speech. According to Abrams, “Figurative language is a conspicuous departure from what users of a language apprehend as the standard meaning of words, or else the standard order to words, in order to achieve some special meaning or effect.” It can be clear that figurative language is not common from the language that we use in daily. -

Hyperbolic Language and Its Relation to Metaphor and Irony

© 2015. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Hyperbolic Language and its Relation to Metaphor and Irony Abstract Hyperbolic use of language is very frequent but has seldom been thought worthy of serious analytical attention. Hyperbole is usually treated as a minor trope which belongs with one or the other of the two dominant figurative uses of language, metaphor and irony. In this paper, we examine the range of ways in which hyperbole is manifest, in both its ‘pure’ uses and its prevalent co-occurrences with other tropes. We conclude that it does not align closely with either metaphor or irony but is a distinctive figure of speech in its own right, characterized by the blatant exaggeration of a relevant scalar property for the purpose of expressing an evaluation of a state of affairs. The relative simplicity of hyperbole enables its exploitation of a range of independent mechanisms of non-literal linguistic communication including loose use, metaphor, simile, and expressions of ironical and other attitudes. Keywords: hyperbole, metaphor, irony, quantitative shift, qualitative shift, evaluative component 1. Introduction Hyperbole is one of the most widely used figures of speech, and yet it remains significantly understudied in comparison with other figures like metaphor, simile, metonymy and irony. The reason for this may be that it is considered a less interesting, substantial or effective use of language, perhaps even facile or trivial, as compared with these other figures, whose employment requires greater verbal skill and whose effects on hearers and readers are more powerful.