Preserving Jamestown, Rhode Island the How and Why of Safeguarding an Island’S Historic Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

The Parking Committee's Report on Public Shoreline Access and Rights

The Parking Committee’s Report on Public Shoreline Access and Rights-of-Way in Jamestown April 7, 1999 Prepared by committee members: Lisa Bryer Claudette Cotter Darcy Magratten Pat Bolger It is not the intent of this study to comment on the status of private versus public ownership on any rights-of-way (ROW). Rather, this study endeavors to compile a list of all CRMC-designated rights-of-way, identified potential ROWs, and public shoreline access points in Jamestown for the purpose of description, review and recommendations to the Town Council for future planning purposes. SIZE, OWNERSHIP & DESCRIPTION: In this report, we have relied upon the work of Rebecca Carlisle, Planning Office intern in the summer of 1992 (a report she compiled which was later forwarded to CRMC and has become the basis of identifying ROWs in Jamestown), the CRMC progress report as of June 1998, reference to the Coastal Resource Center’s publication "Public Access to the Rhode Island Coast", survey maps drawn by Robert Courneyor as part of Rebecca Carlisle’s report, Jamestown Planning Offices plat maps, Jamestown GIS material and recent photographs. REVIEW: Each member of the subcommittee visited, walked, noted current conditions, discussed each site, and also reviewed prior recommendations where applicable. The review took into consideration how accessible each site was–both by car and foot, the access & grade to the shoreline, the proximity of neighbors, the availability of parking, the availability of trash receptacles and other recreational facilities. RECOMMENDATIONS: A rating system of 1 to 3 was used to prioritize each site. Number 1 sites should be fully supported and maintained with existing parking and facilities. -

Jamestown, Rhode Island

Historic andArchitectural Resources ofJamestown, Rhode Island 1 Li *fl U fl It - .-*-,. -.- - - . ---... -S - Historic and Architectural Resources of Jamestown, Rhode Island Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission 1995 Historic and Architectural Resources ofJamestown, Rhode Island, is published by the Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission, which is the state historic preservation office, in cooperation with the Jamestown Historical Society. Preparation of this publication has been funded in part by the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. The contents and opinions herein, however, do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. The Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission receives federal funds from the National Park Service. Regulations of the United States Department of the Interior strictly prohibit discrimination in departmental federally assisted programs on the basis of race, color, national origin, or handicap. Any person who believes that he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of federal assistance should write to: Director, Equal Opportunity Program, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, P.O. Box 37127, Washington, D.C. 20013-7127. Cover East Fern’. Photograph c. 1890. Couriecy of Janiestown Historical Society. This view, looking north along tile shore, shows the steam feriy Conanicut leaving tile slip. From left to rig/It are tile Thorndike Hotel, Gardner house, Riverside, Bay View Hotel and tile Bay Voyage Inn. Only tile Bay Voyage Iiii suivives. Title Page: Beavertail Lighthouse, 1856, Beavertail Road. Tile light/louse tower at the southern tip of the island, the tallest offive buildings at this site, is a 52-foot-high stone structure. -

City of Newport Comprehensive Harbor Management Plan

Updated 1/13/10 hk Version 4.4 City of Newport Comprehensive Harbor Management Plan The Newport Waterfront Commission Prepared by the Harbor Management Plan Committee (A subcommittee of the Newport Waterfront Commission) Version 1 “November 2001” -Is the original HMP as presented by the HMP Committee Version 2 “January 2003” -Is the original HMP after review by the Newport . Waterfront Commission with the inclusion of their Appendix K - Additions/Subtractions/Corrections and first CRMC Recommended Additions/Subtractions/Corrections (inclusion of App. K not 100% complete) -This copy adopted by the Newport City Council -This copy received first “Consistency” review by CRMC Version 3.0 “April 2005” -This copy is being reworked for clerical errors, discrepancies, and responses to CRMC‟s review 3.1 -Proofreading – done through page 100 (NG) - Inclusion of NWC Appendix K – completely done (NG) -Inclusion of CRMC comments at Appendix K- only “Boardwalks” not done (NG) 3.2 -Work in progress per CRMC‟s “Consistency . Determination Checklist” : From 10/03/05 meeting with K. Cute : From 12/13/05 meeting with K. Cute 3.3 -Updated Approx. J. – Hurricane Preparedness as recommend by K. Cute (HK Feb 06) 1/27/07 3.4 - Made changes from 3.3 : -Comments and suggestions from Kevin Cute -Corrects a few format errors -This version is eliminates correction notations -1 Dec 07 Hank Kniskern 3.5 -2 March 08 revisions made by Hank Kniskern and suggested Kevin Cute of CRMC. Full concurrence. -Only appendix charts and DEM water quality need update. Added Natural -

Location ^

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT SHEETlNTETttete. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Windmill Hill Historic District AND/OR COMMON LOCATION ^ ^ r -o.^,,r.,<t^-^.- STREET&NUMBER Eldred Avenue" and North Main Road NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT J ame s t own JL. VICINITY OF #1 Rep. Fernand J. St Germain STATE CODE COUNTY n'nsCODE Rhode Island 44 Newnnrt CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED XAGRICULTURE ^MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Multiple,, , . „ STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC. Jamestown Town Hall STREET& NUMBER 71 Narragansett Avenue CITY, TOWN STATE Jamestown Rhode Island 02835 3 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Jamestown Broadbrush Survey; National Register DATE August, 1975 ^FEDERAL X_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS . Historical Preservation Commission 150 Benefit Street CITY. TOWN STATE Providence Rhode Island DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED JOJNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE _GOOD —RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Windmill Hill Historic District includes approximately 772 acres on Conanicut Island bounded by Eldred Avenue on the north. East Shore Road on- the east, Great Creek on the south and Narragansett Bay on the west. -

How Narragansett Bay Shaped Rhode Island

How Narragansett Bay Shaped Rhode Island For the Summer 2008 issue of Rhode Island History, former director of the Naval War College Museum, Anthony S. Nicolosi, contributed the article, “Rear Admiral Stephen B. Luce, U.S.N, and the Coming of the Navy to Narragansett Bay.” While the article may prove too specialized to directly translate into your classroom, the themes and topics raised within the piece can fit easily into your lesson plans. We have created a handful of activities for your classes based on the role that Narragansett Bay has played in creating the Rhode Island in which we now live. The first activity is an easy map exercise. We have suggested a link to a user-friendly map, but if you have one that you prefer, please go ahead and use it! The goal of this activity is to get your students thinking about the geography of the state so that they can achieve a heightened visual sense of the bay—to help them understand its fundamental role in our development. The next exercise, which is more advanced, asks the students to do research into the various conflicts into which this country has entered. It then asks them, in groups, to deduce what types of ships, weapons, battles and people played a part in each of these wars, and of course, how they relate to Narragansett Bay. We hope that your students will approach the end result creatively by styling their charts after maritime signal “flags.” Exploring the Ocean State Rhode Island is the smallest state, measuring forty-eight miles from North to South and thirty-seven miles from east to west. -

Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 60, No. 1 Massachusetts Archaeological Society

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Journals and Campus Publications Society Spring 1999 Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 60, No. 1 Massachusetts Archaeological Society Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/bmas Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Copyright © 1999 Massachusetts Archaeological Society This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. BULLETIN OF THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 60 (1) SPRING 1999 CONTENTS: Symbols in Stone: Chiastolites in New England Archaeology Curtiss Hoffman, Maryanne MacLeod, and Alan Smith 2 The Conklin Jasper Quarry Site (RI 1935): Native Exploitation of a Local Jasper Source Joseph N. Waller, Jr. 18 The History of "King Philip's War Club" Michael A. Volmar 25 A Hybrid Point Type in the Narragansett Basin: Orient Stemmed Alan Leveillee and Joseph N. Waller, Jr. 30 The Strange Emergence of a Deep Sea Plummet off Plymouth's Gurnet Head Bernard A. Otto 35 Contributors Editor's Note THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, Inc. P.O.Box 700, Middleborough, Massachusetts 02346 MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Officers: Darrell C. Pinckney, P.O. Box 573, Bridgewater, MA 02324 ......................... President Donald Gammons, 7 Virginia Drv., Lakeville, MA 02347 ....................... Vice President Wilford H. Couts Jr., 127 Washburn St., Northboro, MA 01532 Clerk George Gaby, 6 Hazel Rd., Hopkinton, MA 01748 Treasurer Eugene Winter, 54 Trull Ln., Lowell, MA 01852 Museum Coordinator, past President Shirley Blancke, 579 Annursnac Hill Rd., Concord, MA 01742 Bulletin Editor Elizabeth Duffek, 280 Village St. J-1, Medway, MA 02053 ............... -

Part Xvi - Menhaden Regulations

R.I. Marine Fisheries Statutes and Regulations PART XVI - MENHADEN REGULATIONS 16.1 Prohibition on the Harvesting of Menhaden for Reduction Processing – The taking of menhaden for reduction (fish meal) purposes is prohibited in Rhode Island waters. A vessel will be considered in the reduction (fish meal) business if any portion of the vessel’s catch is sold for reduction. (RIMF REGULATIONS) [Penalty - Part 3.3; (RIGL 20-3-3)] 16.2 Narragansett Bay Menhaden Management Area – Narragansett Bay, in its entirety, is designated a Menhaden Management Area. The area shall include the east and west passages of Narragansett Bay, Mt. Hope Bay, and the Sakonnet River, and be bordered on the south by a line from Bonnet Point to Beavertail Point to Castle Hill Light. The southern boundary further extends from Land's End to Sachuest Point and then to Sakonnet Light. The following regulations govern all commercial menhaden operations conducted in the Narragansett Bay Menhaden Management Area. 16.2.1 Gear Restrictions --The use of purse seines shall be permitted only in accordance with the following terms and conditions: (A) All nets shall be less than 100 fathoms (600 feet) in length and less than 15 fathoms (90 feet) in depth. (B) All nets shall be marked with fluorescent-colored float buoys, distinguishable from the other float buoys on the net, at intervals of 50 feet. (C) Annually, prior to use, all nets shall be inspected and certified as being in conformance with the provisions of this section by the DEM Division of Law Enforcement. Once inspected and certified, a net may be used throughout the duration of the calendar year in which it was inspected, provided that it is not altered with regard to any of the provisions of this section. -

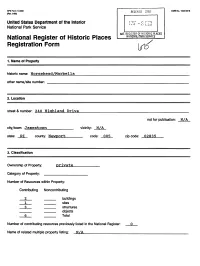

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NPS Form 10-000 RECEIVED 2230 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior f--n< *'<« U "*' ,...« National Park Service NAT. REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Registration Form 1. Name of Property historic name: Horsehead/Marbella other name/site number: 2. Location street & number: 240 Highland Drive not for publication: N/A city/town: Jamestown_________ vicinity: N/A state: RI county: Newport______ code: 005 zip code: 02835 3. Classification Ownership of Property: private Category of Property: Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing __2 buildings sites structures objects Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 0 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A____________ NPS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number ——— Page ___ SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 99000675 Date Listed: 6/16/99 Property Name:Horsehead Marbella County:Newport State: R[ Multiple Name: N/A This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. f^\ Signature of the Keeper Date of Action Amended Items in Nomiantion: In Section 3 of the form (Classification), the category of the property is not given. An amendment is made to note the category of the property as building because the house, carriage house/barn, and the surrounding designed landscape are a historically and functionally related unit. -

Historic Context for Department of Defense Facilities World War Ii Permanent Construction

DEPARTMeNT OF DEFENSE FACILITIES- WORLD WAR II PERMANENT CONSTRUhttp://aee-www.apgea.army.mil:8080/prod/usaee!eqlconserv/ww2pel.htm ~ - Delivery Order 21 Contract No. DACW31-89-D-0059 US Army Corps of Engineers-Baltimore District HISTORIC CONTEXT FOR DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE FACILITIES WORLD WAR II PERMANENT CONSTRUCTION May 1997 R. Christopher Goodwin and Associates, Inc. 241 E. Fourth Street Suite 100 Frederick, Maryland 21701 FINAL REPORT June 1997 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Historic Context for Department of Defense (DoD) World War H Permanent Construction combines two previous reports: Historic Context for Department of Defense Facilities World War H Permanent Construction (Hirrel et al., draft June 1994) and Methodology for World War H Permanent Construction (Whelan, draft August 1996). This project was designed to meet the following objectives: • To analyze and synthesize historical data on the military's permanent construction program during World War H. • To assist DoD cultural resource managers and other DoD personnel with fulfilling their responsibilities under the National Historic Preservation Act (NHP A) of 1966, as amended. Section 110 of the NHPA requires federal agencies to identity, evaluate, and nominate to the National Register of Historic Places historic properties under their jurisdiction. Section 110 Guidelines, developed by the National Park Service, U.S. Department ofthe Interior, direct federal agencies to establish historic contexts to identifY and evaluate historic properties (53FR 4727-46). • To develop a consistent historic context framework that provides comparative data and background information in a cost-effective manner, which will allow DoD personnel to assess the relative significance of World War II military construction. -

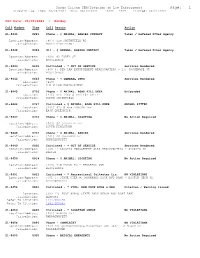

Page: 1 Dispatch Log From: 06/06/2021 Thru: 06/12/2021 0000 - 2359 Printed: 06/21/2021

Rhode Island DEM/Division of Law Enforcement Page: 1 Dispatch Log From: 06/06/2021 Thru: 06/12/2021 0000 - 2359 Printed: 06/21/2021 For Date: 06/06/2021 - Sunday Call Number Time Call Reason Action 21-9441 0221 Phone - @ ANIMAL, RABIES CONTACT Taken / Refered Other Agency Location/Address: [407] 528 SMITHFIELD RD Jurisdiction: NORTH PROVIDENCE 21-9442 0304 911 - @ ANIMAL, RABIES CONTACT Taken / Refered Other Agency Location/Address: [409] 93 TOBEY ST Jurisdiction: PROVIDENCE 21-9443 0632 Initiated - * OUT OF SERVICE Services Rendered Location/Address: [409 6] DEM LAW ENFORCEMENT HEADQUARTERS - 235 PROMENADE ST Jurisdiction: PROVIDENCE 21-9444 0646 Phone - + GENERAL INFO Services Rendered Location: [417] Jurisdiction: D E M LAW ENFORCEMENT 21-9445 0720 Phone - @ ANIMAL, ROAD KILL DEER Unfounded Location: [415] RTE 146S @ RTE146A SPLIT Jurisdiction: NORTH SMITHFIELD 21-9446 0727 Initiated - @ ANIMAL, ROAD KILL DEER ANIMAL PITTED Location: [202] 95S @ NEW LONDON TPK Jurisdiction: EAST GREENWICH 21-9447 0733 Phone - @ ANIMAL, SIGHTING No Action Required Location/Address: [503] 56 SABBATIA TRL Jurisdiction: SOUTH KINGSTOWN 21-9448 0737 Phone - @ ANIMAL, RABIES Services Rendered Location/Address: [501] 20 OVERLOOK RD Jurisdiction: NARRAGANSETT 21-9449 0802 Initiated - * OUT OF SERVICE Services Rendered Location/Address: [508 4] ARCADIA MANAGEMENT AREA HEADQUARTERS - ARCADIA RD Jurisdiction: EXETER 21-9450 0818 Phone - @ ANIMAL, SIGHTING No Action Required Location/Address: [409] 95N PRIOR TO - THURBERS AVE Jurisdiction: PROVIDENCE 21-9451 0822 -

Conanicut Battery

7- Si 4 Form O-3OO UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 1ST ATE: July 1969 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE I Rhode Island COUNTY, NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Newport INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE Type all entries - complete applicable sections .. .. COMMON! Conanicut Battery AND/OR HISTORIC; LOCATION STREET AND NUMBER; To the west of the northern çertion of Beaver Tail Road CITY OR TOWN: Jan-iestown STATE CODE IC0U1’T CO OE Rhode Island, 02835 bh Newport UU5 C3OR’ ACCESSIBLE I’, OWNERSHIP STATUS Chock One TO THE PUBLIC [] Distiir.t flJ B!jilding [J Public Public Acquisition: El Occupied Yes: C Restricted Site [_J Structure 0 Private El In Process Unoccupied El Unrestricted ii Ob.t El Both El Beipg Considered o Preservation work I in progress 0 No 1 PRESENT USE Check Ono or More as Appropriate =, Agricultural Government Pork Transportation Comments El - El El El Commercial El Industrial El Privote Residence El Other Specify I El Educational fl Military fl Religious j El Entertainment Ii Museum El Scientific r Eioit!!aurF3Rvv -- DWNER5 Fl AME; a -l Town of Jamestown -I LU STREET AND NUMBER; In LU 71 Narragansett Avenue In CITY OR TOWN; STATE: CODE Rhode Island, 02835 -- ±me6tln roos LOcATIONOE LEGAL DESCRIPTION cOu RTMOUSE. REGISTRY OF OEED5. ETC: n 0 Town Clerk C z STREET AND NUMBER: -l 71 Narragansett Avenue CITY OR TOWN; STATE CODE Jamestown Rhode Island, 02835 FIThEPRESENTATIONIN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE OF SURVEY Not sO represented DATE OF SURVEY: El Federal El State El County El Local -- DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS; C Z t o In STREET ANO NUMBER; 0 CITY OR TOWN: - STATE; CODE ______________________________ S.’ 5.