The Desert Fireball Network: a New Era for Space Science in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olivine and Pyroxene from the Mantle of Asteroid 4 Vesta ∗ Nicole G

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 418 (2015) 126–135 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Olivine and pyroxene from the mantle of asteroid 4 Vesta ∗ Nicole G. Lunning a, , Harry Y. McSween Jr. a,1, Travis J. Tenner b,2, Noriko T. Kita b,3, Robert J. Bodnar c,4 a Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences and Planetary Geosciences Institute, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA b Department of Geosciences, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA c Department of Geosciences, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: A number of meteorites contain evidence that rocky bodies formed and differentiated early in our solar Received 25 September 2014 system’s history, and similar bodies likely contributed material to form the planets. These differentiated Received in revised form 25 February 2015 rocky bodies are expected to have mantles dominated by Mg-rich olivine, but direct evidence for such Accepted 25 February 2015 mantles beyond our own planet has been elusive. Here, we identify olivine fragments (Mg# = 80–92) in Available online 17 March 2015 howardite meteorites. These Mg-rich olivine fragments do not correspond to an established lithology Editor: T. Mather in the howardite–eucrite–diogenite (HED) meteorites, which are thought to be from the asteroid 4 Keywords: Vesta; their occurrence in howardite breccias, combined with diagnostic oxygen three-isotope signatures planetary formation and minor element chemistry, indicates they are vestan. -

Assessment of the Mesosiderite-Diogenite Connection and an Impact Model for the Genesis of Mesosiderites

45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2014) 2554.pdf ASSESSMENT OF THE MESOSIDERITE-DIOGENITE CONNECTION AND AN IMPACT MODEL FOR THE GENESIS OF MESOSIDERITES. T. E. Bunch1,3, A. J. Irving2,3, P. H. Schultz4, J. H. Wittke1, S. M. Ku- ehner2, J. I. Goldstein5 and P. P. Sipiera3,6 1Dept. of Geology, SESES, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011 ([email protected]), 2Dept. of Earth & Space Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 3Planetary Studies Foundation, Galena, IL, 4Dept. of Geological Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI, 5Dept. of Geolo- gy, University of Massachusetts, Amherts, MA, 6Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL. Introduction: Among well-recognized meteorite 34) is the most abundant silicate mineral and in some classes, the mesosiderites are perhaps the most com- clasts contains inclusions of FeS, tetrataenite, merrillite plex and petrogenetically least understood. Previous and silica. Three of the ten norite clasts contain a few workers have contributed important information about tiny grains of olivine (Fa24-32). A single, fine-grained “classic” falls and Antarctic finds, and have proposed breccia clast was found in NWA 5312 (see Figure 2). several different models for mesosiderite genesis [1]. Unlike the case of pallasites, the co-occurrence of met- al and silicates (predominantly orthopyroxene and cal- cic plagioclase) in mesosiderites is inconsistent with a single-stage “igneous” history, and instead seems to demand admixture of at least two separate compo- nents. Here we review the models in light of detailed ex- amination of multiple specimens from a very large mesosiderite strewnfield in Northwest Africa. Many specimens (totaling at least 80 kilograms) from this area (probably in Algeria) have been classified sepa- rately by us and others; however, in most cases the Figure 1. -

Orbit and Dynamic Origin of the Recently Recovered Annama’S H5 Chondrite

ORBIT AND DYNAMIC ORIGIN OF THE RECENTLY RECOVERED ANNAMA’S H5 CHONDRITE Josep M. Trigo-Rodríguez1 Esko Lyytinen2 Maria Gritsevich2,3,4,5,8 Manuel Moreno-Ibáñez1 William F. Bottke6 Iwan Williams7 Valery Lupovka8 Vasily Dmitriev8 Tomas Kohout 2, 9, 10 Victor Grokhovsky4 1 Institute of Space Science (CSIC-IEEC), Campus UAB, Facultat de Ciències, Torre C5-parell-2ª, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Finnish Fireball Network, Helsinki, Finland. 3 Dept. of Geodesy and Geodynamics, Finnish Geospatial Research Institute (FGI), National Land Survey of Finland, Geodeentinrinne 2, FI-02431 Masala, Finland 4 Dept. of Physical Methods and Devices for Quality Control, Institute of Physics and Technology, Ural Federal University, Mira street 19, 620002 Ekaterinburg, Russia. 5 Russian Academy of Sciences, Dorodnicyn Computing Centre, Dept. of Computational Physics, Valilova 40, 119333 Moscow, Russia. 6 Southwest Research Institute, 1050 Walnut St., Suite 300, Boulder, CO 80302, USA. 7Astronomy Unit, Queen Mary, University of London, Mile End Rd. London E1 4NS, UK. 8 Moscow State University of Geodesy and Cartography (MIIGAiK), Extraterrestrial Laboratory, Moscow, Russian Federation 9Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 64, 00014 Helsinki University, Finland 10Institute of Geology, The Czech Academy of Sciences, Rozvojová 269, 16500 Prague 6, Czech Republic Abstract: We describe the fall of Annama meteorite occurred in the remote Kola Peninsula (Russia) close to Finnish border on April 19, 2014 (local time). The fireball was instrumentally observed by the Finnish Fireball Network. From these observations the strewnfield was computed and two first meteorites were found only a few hundred meters from the predicted landing site on May 29th and May 30th 2014, so that the meteorite (an H4-5 chondrite) experienced only minimal terrestrial alteration. -

Possible Fluid Rock Interactions on Differentiated Asteroids Recorded in Eucritic Meteorites Jean-Alix Barrat, A

Possible fluid rock interactions on differentiated asteroids recorded in eucritic meteorites Jean-Alix Barrat, A. Yamaguchi, T.E. Bunch, Marcel Bohn, Claire Bollinger, Georges Ceuleneer To cite this version: Jean-Alix Barrat, A. Yamaguchi, T.E. Bunch, Marcel Bohn, Claire Bollinger, et al.. Possible fluid rock interactions on differentiated asteroids recorded in eucritic meteorites. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, Elsevier, 2011, 75 (13), pp.3839-3852. insu-00586415 HAL Id: insu-00586415 https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-00586415 Submitted on 15 Apr 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Possible fluid-rock interactions on differentiated asteroids recorded in eucritic meteorites by J.A. Barrat 1,2 , A. Yamaguchi 3,4 , T.E. Bunch 5, M. Bohn 1,2 , 1,2 6 C. Bollinger , and G. Ceuleneer 1Université Européenne de Bretagne, France. 2CNRS UMR 6538 (Domaines Océaniques), U.B.O.-I.U.E.M., Place Nicolas Copernic, 29280 Plouzané Cedex, France. E-Mail: [email protected] . 3National Institute of Polar Research, Tachikawa, Tokyo 190-8518, Japan 4Department of Polar Science, School of Multidisciplinary Science, Graduate University for Advanced Sciences, Tokyo 190-8518, Japan. -

Meteorite Dunite Breccia Mil 03443: a Probable Crustal Cumulate Closely Related to Diogenites from the Hed Parent Asteroid

METEORITE DUNITE BRECCIA MIL 03443: A PROBABLE CRUSTAL CUMULATE CLOSELY RELATED TO DIOGENITES FROM THE HED PARENT ASTEROID. David W Mittlefehldt, Astromateri- als Research Office, NASA/Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas, USA, ([email protected]). Introduction: There are numerous types of differ- Metal is very rare, and occurs as grains a few microns entiated meteorites, but most represent either the crusts in size associated with troilite. or cores of their parent asteroids. Ureilites, olivine- pyroxene-graphite rocks, are exceptions; they are man- tle restites [1]. Dunite is expected to be a common mantle lithology in differentiated asteroids. In particu- lar, models of the eucrite parent asteroid contain large volumes of dunite mantle [2-4]. Yet dunites are very rare among meteorites, and none are known associated with the howardite, eucrite, diogenite (HED) suite. Spectroscopic measurements of 4 Vesta, the probable HED parent asteroid, show one region with an olivine signature [5] although the surface is dominated by ba- saltic and orthopyroxenitic material equated with eucrites and diogenites [6]. One might expect that a small number of dunitic or olivine-rich meteorites might be delivered along with the HED suite. The 46 gram meteoritic dunite MIL 03443 (Fig. 1) Figure 2. BSE image of MIL 03443 showing its gen- was recovered from the Miller Range ice field of Ant- eral fragmental breccia texture, and primary texture arctica. This meteorite was tentatively classified as a between olivine, orthopyroxene and chromite. mesosiderite because large, dunitic clasts are found in this type of meteorite, but it was noted that MIL 03443 could represent a dunite sample of the HED suite [7]. -

JEM-EUSO: Meteor and Nuclearite Observations

Exp Astron DOI 10.1007/s10686-014-9375-4 ORIGINAL ARTICLE JEM-EUSO: Meteor and nuclearite observations M. Bertaina A. Cellino F. Ronga The JEM-EUSO· Collaboration· · Received: 22 August 2013 / Accepted: 24 February 2014 ©SpringerScience+BusinessMediaDordrecht2014 Abstract Meteor and fireball observations are key to the derivation of both the inven- tory and physical characterization of small solar system bodies orbiting in the vicinity of the Earth. For several decades, observation of these phenomena has only been possible via ground-based instruments. The proposed JEM-EUSO mission has the potential to become the first operational space-based platform to share this capabil- ity. In comparison to the observation of extremely energetic cosmic ray events, which is the primary objective of JEM-EUSO, meteor phenomena are very slow, since their typical speeds are of the order of a few tens of km/sec (whereas cosmic rays travel at light speed). The observing strategy developed to detect meteors may also be applied to the detection of nuclearites, which have higher velocities, a wider range of possible trajectories, but move well below the speed of light and can therefore be considered as slow events for JEM-EUSO. The possible detection of nuclearites greatly enhances the scientific rationale behind the JEM-EUSO mission. Keywords Meteors Nuclearites JEM-EUSO Space detectors · · · M. Bertaina (!) Dipartimento di Fisica, Universit`adiTorino,INFNTorino,viaP.Giuria1,10125Torino,Italy e-mail: [email protected] A. Cellino (!) INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Torino, Strada Osservatorio 20, 10025 Pino Torinese (TO), Italy e-mail: [email protected] F. Ronga (!) Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare - Laboratori Nazionali di Frascati, Via E. -

Physical and Dynamical Properties of the Unusual V-Type Asteroid (2579) Spartacus Dagmara Oszkiewicz1, Agnieszka Kryszczynska´ 1, Paweł Kankiewicz2, Nicholas A

A&A 623, A170 (2019) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833641 & © ESO 2019 Astrophysics Physical and dynamical properties of the unusual V-type asteroid (2579) Spartacus Dagmara Oszkiewicz1, Agnieszka Kryszczynska´ 1, Paweł Kankiewicz2, Nicholas A. Moskovitz3, Brian A. Skiff3, Thomas B. Leith3, Josef Durechˇ 4, Ireneusz Włodarczyk5, Anna Marciniak1, Stefan Geier6,7, Grigori Fedorets8, Volodymyr Troianskyi1,9, and Dóra Föhring10 1 Astronomical Observatory Institute, Faculty of Physics, A. Mickiewicz University, Słoneczna 36, 60-286 Poznan,´ Poland e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Physics, Astrophysics Division, Jan Kochanowski University, Swietokrzyska 15, 25-406 Kielce, Poland 3 Lowell Observatory, 14000 W Mars Hill Road, 86001 Flagstaff, AZ, USA 4 Astronomical Institute, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University, V Holešovickáchˇ 2, 18000 Prague 8, Czech Republic 5 Chorzów Astronomical Observatory MPC553, Chorzów, Polish Amateur Astronomical Society, Powstancow Wlkp. 34, 63-708 Rozdrazew, Poland 6 Gran Telescopio Canarias (GRANTECAN), Cuesta de San José s/n, 38712 Breña Baja, La Palma, Spain 7 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, Vía Láctea s/n, 38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 8 Department of Physics, Gustaf Hällströmin katu 2a, PO Box 64, 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland 9 Astronomical Observatory of Odessa I.I. Mechnikov National University, Marazlievskaya 1v, 65014 Odessa, Ukraine 10 Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA Received 14 June 2018 / Accepted 6 February 2019 ABSTRACT Context. Asteroid (2579) Spartacus is a small V-type object located in the inner main belt. This object shows spectral characteristics unusual for typical Vestoids, which may indicate an origin deeper than average within Vesta or an origin from an altogether different parent body. -

Exploring the Geology of a New Differentiated Basaltic Asteroid

BUNBURRA ROCKHOLE: EXPLORING THE GEOLOGY OF A NEW DIFFERENTIATED BASALTIC ASTEROID. G.K. Benedix1,7, P.A. Bland1,7, J. M. Friedrich2,3, D.W. Mittlefehldt4, M.E. Sanborn5, Q.-Z. Yin5, R.C. Greenwood6, I.A. Franchi6, A.W.R. Bevan7, M.C. Towner1 and Grace C. Perotta2. 1Dept. Applied Geology, Curtin University, GPO Box U1987, Perth, WA, 6845 Australia ([email protected]), 2Dept. Chem., Fordham University, 441 East Fordham Road, Bronx, NY 10458 USA, 3Dept. Earth & Planetary Sciences, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA, 4NASA/Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX, USA, 5Dept. of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California at Davis, Davis, CA 95616, USA, 6Planetary & Space Sci., The Open University, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK, 7Western Australia Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool, WA, 6986, Australia. Introduction: Bunburra Rockhole (BR) is the first versity for chemical analysis. Four of these were ana- recovered meteorite of the Desert Fireball Network [1]. lysed for major and trace elements and two for trace It was initially classified as a basaltic eucrite, based on elements only. Two of these subsamples (A/1 and texture, mineralogy, and mineral chemistry [2] but C/A/2) were analysed at UC Davis to investigate the Cr subsequent O isotopic analyses showed that BR’s isotopic systematics. Homogenized powders from the composition lies significantly far away from the HED two chips were dissolved in Parr bombs for a 96 hour group of meteorites (fig. 1) [1]. This suggested that period at 200°C to insure complete dissolution of re- BR was not a piece of the HED parent body (4 Vesta), fractory minerals such as spinel. -

Hydrated Minerals and Carbonaceous Chondrite Fragments in Lohawat Howardite: Astrobiological Implications: M

Astrobiology Science Conference 2015 (2015) 7069.pdf HYDRATED MINERALS AND CARBONACEOUS CHONDRITE FRAGMENTS IN LOHAWAT HOWARDITE: ASTROBIOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS: M. S. Sisodia, A. Basu Sarbadhikari and R. R. Maha- jan. PLANEX, Physical Reasearch Laboratory, Ahmedabad, India (E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]) Introduction: Presence of hydrated minerals on nebula caused initial melting and subsequent gradual asteroids, which are remnants of the blocks that formed differentiation of these early accreting bodies into the planets of the solar system has great importance for crust, mantle and core [4]. Dawn’s results confirm that deducing the origin of Earth’s water. Asteroid 4 Vesta Vesta is a differentiated protoplanet and that it is a is the parent body of the howardite-eucrite-diogenite parent body of HED meteorites [5]. The presence of (HED) family of the meteorites that have fallen on hydrated minerals on vesta as revealed by Lohawt Earth [1]. Lohawat howardite that fell in India in the howardite is very significant. Howardites originate year 1994 is a heterogeneous breccia composed of va- from the surface of Vesta nad constitute representative riety of mineral and lithic fragments [2]. We report samples from its crust, mantle and core. The low gravi- here optical study of hydrated minerals that we found ty of Vesta induce lower velocities to the impactors in Lohawat howardite and then discuss their astrobio- resulting into incomplete melting of impacting carbo- logical implications. naceous chondrites [6]. Whether these hydrated miner- Petrography of Lohawat howardite: Lohawat als were contributed on the surface of Vesta by carbo- howardite is an assortment of different minerals and naceous chondrites will be revealed by isotope study clasts. -

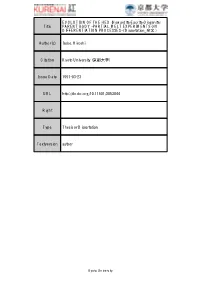

Howardite-Eucrite-Diogenite) Title PARENT BODY -PARTIAL MELT EXPERIMENTS on DIFFERENTIATION PROCESSES-( Dissertation 全文 )

EVOLUTION OF THE HED (Howardite-Eucrite-Diogenite) Title PARENT BODY -PARTIAL MELT EXPERIMENTS ON DIFFERENTIATION PROCESSES-( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Isobe, Hiroshi Citation Kyoto University (京都大学) Issue Date 1991-03-23 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.11501/3053044 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion author Kyoto University 学位 申請論文 磯部博志 EVOLUTION OF THE HED (howardite-eucrite-diogenite) PARENT BODY -PARTIAL MELT EXPERIMENTS ON DIFFERENTIATION PROCESSES- Hiroshi ISOBE Department of Environmental Safety Research Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute Tokai, Ibaraki, 319-11, JAPAN CONTENTS Abstract 1 Introduction1 2 Experiments —starting materials and procedures13 2-1 Composition of the starting materials13 2-2 Experimental procedures19 3 Results and interpretation25 3-1 Mineral assemblages of the run products25 3-2 Composition of the melts and minerals34 4 Discussion60 4-1 Melting relations on the 'pseudo-liquidus' diagrams 60 4-2 Fractionation sequence71 4-3 Physical conditions of the solid-liquid separations 78 4-4 Summary of the present evolution model of HEDP-PB96 Acknowledgments98 References99 Appendix 1 Chemistry of HED and pallasite meteorites106 Appendix 2 Tables of compositions of run products116 Abstract Three series of melting experiments with a chondritic material, a eucrite-diogenite mixture, and a eucritic material were carried out using a one atmosphere gas mixing furnace to illustrate liquidus phase relation and chemical compositions of the phases. Locations of an olivine control line, olivine-pyroxene phase boundary -

Carbonaceous Chondrite-Rich Howardites; the Potential for Hydrous Lithologies on the Hed Parent

CARBONACEOUS CHONDRITE-RICH HOWARDITES; THE POTENTIAL FOR HYDROUS LITHOLOGIES ON THE HED PARENT. J. S. Herrin 1,2 , M. E. Zolensky 2, J. A. Cartwright 3, D. W. Mittle- fehldt 2, and D. K. Ross 1,2 . 1ESCG Astromaterials Research Group, Houston, Texas, USA ( [email protected] ), 2NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas, USA, 3Max Planck Institut für Chemie, Mainz, Germany. Introduction: Howardites, eucrites, and dioge- clasts texturally resembling CM2 up to 7mm occupy- nites, collectively referred to as the “HED’s”, are a ing nearly half of the sample area accompanied 1-5 clan of meteorites thought to represent three different mm subangular impact melt clasts containing relict lithologies from a common parent body. Collectively eucritic fragments. The remaining medium and fine they are the most abundant type of achondrites in terre- fraction of the specimen consists of mm-to-sub-mm strial collections [1]. Eucrites are crustal basalts and angular-to-subrounded eucritic, diogenitic, carbona- gabbros, diogenites are mostly orthopyroxenites and ceous chondrite clasts set in a medium-to-coarse angu- are taken to represent lower crust or upper mantle ma- lar matrix of same materials. The eucrite/diogenite terials, and howardites are mixed breccias containing ratio of identifiable clasts is approximately 50/50. The both lithologies and are generally regarded as derived total modal abundance of visible carbonaceous chon- from the regolith or near-surface. drite fragments is ~60%. The presence of exogenous chondritic material in PRA 04402 is a howardite breccia consisting of howardite breccias has long been recognized [2,3]. As mm-to-sub-mm subrounded-to-subangular diogenite a group, howardites exhibit divergence in bulk chemi- and eucritic clasts in roughly equal proportions set in a stry from what would be produced by mixing of dioge- medium-to-coarse matrix. -

1950 Da, 205, 269 1979 Va, 230 1991 Ry16, 183 1992 Kd, 61 1992

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09684-4 — Asteroids Thomas H. Burbine Index More Information 356 Index 1950 DA, 205, 269 single scattering, 142, 143, 144, 145 1979 VA, 230 visual Bond, 7 1991 RY16, 183 visual geometric, 7, 27, 28, 163, 185, 189, 190, 1992 KD, 61 191, 192, 192, 253 1992 QB1, 233, 234 Alexandra, 59 1993 FW, 234 altitude, 49 1994 JR1, 239, 275 Alvarez, Luis, 258 1999 JU3, 61 Alvarez, Walter, 258 1999 RL95, 183 amino acid, 81 1999 RQ36, 61 ammonia, 223, 301 2000 DP107, 274, 304 amoeboid olivine aggregate, 83 2000 GD65, 205 Amor, 251 2001 QR322, 232 Amor group, 251 2003 EH1, 107 Anacostia, 179 2007 PA8, 207 Anand, Viswanathan, 62 2008 TC3, 264, 265 Angelina, 175 2010 JL88, 205 angrite, 87, 101, 110, 126, 168 2010 TK7, 231 Annefrank, 274, 275, 289 2011 QF99, 232 Antarctic Search for Meteorites (ANSMET), 71 2012 DA14, 108 Antarctica, 69–71 2012 VP113, 233, 244 aphelion, 30, 251 2013 TX68, 64 APL, 275, 292 2014 AA, 264, 265 Apohele group, 251 2014 RC, 205 Apollo, 179, 180, 251 Apollo group, 230, 251 absorption band, 135–6, 137–40, 145–50, Apollo mission, 129, 262, 299 163, 184 Apophis, 20, 269, 270 acapulcoite/ lodranite, 87, 90, 103, 110, 168, 285 Aquitania, 179 Achilles, 232 Arecibo Observatory, 206 achondrite, 84, 86, 116, 187 Aristarchus, 29 primitive, 84, 86, 103–4, 287 Asporina, 177 Adamcarolla, 62 asteroid chronology function, 262 Adeona family, 198 Asteroid Zoo, 54 Aeternitas, 177 Astraea, 53 Agnia family, 170, 198 Astronautica, 61 AKARI satellite, 192 Aten, 251 alabandite, 76, 101 Aten group, 251 Alauda family, 198 Atira, 251 albedo, 7, 21, 27, 185–6 Atira group, 251 Bond, 7, 8, 9, 28, 189 atmosphere, 1, 3, 8, 43, 66, 68, 265 geometric, 7 A- type, 163, 165, 167, 169, 170, 177–8, 192 356 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09684-4 — Asteroids Thomas H.