Introduction to the UCC Book of Worship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Slow Integration of Instruments Into Christian Worship

Musical Offerings Volume 8 Number 1 Spring 2017 Article 2 3-28-2017 From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship Jonathan M. Lyons Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Christianity Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Lyons, Jonathan M. (2017) "From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship," Musical Offerings: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2017.8.1.2 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol8/iss1/2 From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship Document Type Article Abstract The Christian church’s stance on the use of instruments in sacred music shifted through influences of church leaders, composers, and secular culture. Synthesizing the writings of early church leaders and church historians reveals a clear progression. The early musical practices of the church were connected to the Jewish synagogues. As recorded in the Old Testament, Jewish worship included instruments as assigned by one’s priestly tribe. -

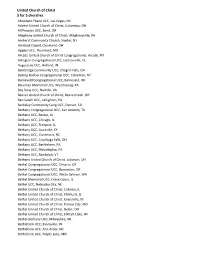

2017 5 for 5 Churches

United Church of Christ 5 for 5 churches Abundant Peace UCC, Las Vegas, NV Advent United Church of Christ, Columbus, OH All Peoples UCC, Bend, OR Allegheny United Church of Christ, Alleghenyville, PA Amherst Community Church, Snyder, NY Amistad Chapel, Cleveland, OH Apples UCC, Thurmont, MD Arcade United Church of Christ Congregational, Arcade, NY Arlington Congregational UCC, Jacksonville, FL Augustana UCC, Holland, IN Bainbridge Community UCC, Chagrin Falls, OH Baiting Hollow Congregational UCC, Calverton, NY Barneveld Congregational UCC, Barneveld, WI Bausman Memorial UCC, Wyomissing, PA Bay View UCC, Norfolk, VA Beaver United Church of Christ, Beavercreek, OH Ben Salem UCC, Lehighton, PA Berkeley Community Cong UCC, Denver, CO Bethany Congregational UCC, San Antonio, TX Bethany UCC, Baxter, IA Bethany UCC, Chicago, IL Bethany UCC, Freeport, IL Bethany UCC, Louisville, KY Bethany UCC, Claremont, NC Bethany UCC, Cuyahoga Falls, OH Bethany UCC, Bethlehem, PA Bethany UCC, Philadelphia, PA Bethany UCC, Randolph, VT Bethany United Church of Christ, Lebanon, OH Bethel Congregational UCC, Ontario, CA Bethel Congregational UCC, Beaverton, OR Bethel Congregational UCC, White Salmon, WA Bethel Memorial UCC, Creve Coeur, IL Bethel UCC, Nebraska City, NE Bethel United Church of Christ, Cahokia, IL Bethel United Church of Christ, Elmhurst, IL Bethel United Church of Christ, Evansville, IN Bethel United Church of Christ, Kansas City, MO Bethel United Church of Christ, Beloit, OH Bethel United Church of Christ, Elkhart Lake, WI Bethel-Bethany UCC, -

United Church of Christ

United Church of Christ Religious Beliefs and Healthcare Decisions by Arlene K. Nehring he United Church of Christ (UCC) was born out T of, and continues to shape and be shaped by, the ecumenical movement—the attempt of Christians to unite around matters of agreement rather than to divide over matters of disagreement. In 1957, two denominations merged, the Congregational Christian Churches and the Evangelical and Reformed Church, Contents resulting in the United Church of Christ. The Individual and 2 Although the UCC is usually viewed as an heir to the Patient-Caregiver Relationship the Reformed Protestant tradition, the denomination also includes historic Lutheran roots among the tradi- Family, Sexuality, and Procreation 3 tions that inform its faith and practice. The UCC is Genetics 5 sometimes described as a “non-creedal” church Mental Health 6 because no specific confession or set of confessional statements is considered normative for the church’s Death and Dying 8 faith. But UCC beliefs can be gleaned not only from Special Concerns 9 the numerous confessions that the church has actual- ly employed, but also from the traditions reflected in its worship and other practices, such as confirmation. From this perspective, the UCC might better be described as a “multi-creedal, multi-confessional” church. It embraces a rich Protestant heritage in which the primary authority of the Scriptures, justifi- cation by grace through faith, and the continuing guidance of the Holy Spirit are all central tenets. Although the UCC also features enormous theological diversity, two other key principles are embraced by virtually all its members. -

Principles of Worship and Liturgy

Perspective Digest Volume 16 Issue 1 Winter Article 3 2011 Principles of Worship and Liturgy Fernando Canale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pd Part of the Liturgy and Worship Commons Recommended Citation Canale, Fernando (2011) "Principles of Worship and Liturgy," Perspective Digest: Vol. 16 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pd/vol16/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Adventist Theological Society at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Perspective Digest by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Canale: Principles of Worship and Liturgy Worship and liturgy should reflect something far more than culture or personal preference. By Fernando Canale Many church members are bewildered by the multiplicity of Christian styles of worship. Usually, when believers are talking about these feelings, the conversation ends when someone asserts that the reasons for disliking a form of worship are cultural. Culture shapes taste. Thus, the reasoning follows, if the new style is accepted, with time it will become liked. Are worship styles1 a matter of taste or a matter of principle? Is corporate taste a reliable principle to shape our corporate worship style? Are there principles that can be used to help shape worship and to choose what to include in it? Page 1 of 26 Published by Digital Commons @ Andrews University, 2011 1 Perspective Digest, Vol. 16 [2011], Iss. 1, Art. 3 Many believers have worshiped God since their early youth. -

Principles for Worship

Principles for Worship Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Published by Augsburg Fortress RENEWING WORSHIP 2 Principles for Worship This resource has been prepared by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America for provisional use. Copyright © 2002 Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. Published by Augsburg Fortress, Publishers. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews and for uses described in the following paragraph, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Contact: Permissions, Augs- burg Fortress, Box 1209, Minneapolis MN 55440-1209, (800) 421-0239. Permission is granted to reproduce the material on pages i- 154 for study and response, provided that no part of the re- production is for sale, copies are for onetime local use, and the following copyright notice appears: From Principles for Worship, copyright © 2002, administered by Augsburg Fortress. May be reproduced by permission for use only be- tween June 1, 2002 and December 31, 2005. Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible © 1989 Division of Christ- ian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. Prayers and liturgical texts acknowledged as LBW are copyright © 1978 Lutheran Book of Worship and those acknowledged as With One Voice are copyright © 1995 Augsburg Fortress. The Use of the Means of Grace: A Statement on the Practice of Word and Sacrament, included as the appendix in this volume, was adopted for guidance and practice by the Fifth Biennial Churchwide Assembly of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, August 19, 1997. -

Reformed Tradition

THE ReformedEXPLORING THE FOUNDATIONS Tradition: OF FAITH Before You Begin This will be a brief overview of the stream of Christianity known as the Reformed tradition. The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, the Reformed Church in America, the United Church of Christ, and the Christian Reformed Church are among those considered to be churches in the Reformed tradition. Readers who are not Presbyterian may find this topic to be “too Presbyterian.” We encourage you to find out more about your own faith tradition. Background Information The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) is part of the Reformed tradition, which, like most Christian traditions, is ancient. It began at the time of Abraham and Sarah and was Jewish for about two thousand years before moving into the formation of the Christian church. As Christianity grew and evolved, two distinct expressions of Christianity emerged, and the Eastern Orthodox expression officially split with the Roman Catholic expression in the 11th century. Those of the Reformed tradition diverged from the Roman Catholic branch at the time of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. Martin Luther of Germany precipitated the Protestant Reformation in 1517. Soon Huldrych Zwingli was leading the Reformation in Switzerland; there were important theological differences between Zwingli and Luther. As the Reformation progressed, the term “Reformed” became attached to the Swiss Reformation because of its insistence on References Refer to “Small Groups 101” in The Creating WomanSpace section for tips on leading a small group. Refer to the “Faith in Action” sections of Remembering Sacredness for tips on incorporating spiritual practices into your group or individual work with this topic. -

Massachusetts Conference, United Church of Christ

THE INTERIM MINISTRY HANDBOOK of the New Hampshire Conference, United Church of Christ Contents I. An Introduction to Interim Ministry II. A Shared Ministry: Responsibilities and Expectations A. Policies Concerning Interim Ministry B. Characteristics of the Interim Minister C. Compensation Guidelines D. Contractual Concerns E. Guidelines Concerning Responsibilities and Expectations F. Additional Suggestions III. Interim Ministry Profile III. A Covenant for Interim Pastorates V. Background Disclosure This Handbook is intended primarily as a resource for Interim Ministers. Approved by the Interim Ministry Group and the Conference Minister of the New Hampshire Conference of the United Church of Christ, November, 1998 Updated 9/04 Updated 1/11 2 An Introduction to Interim Ministry The interim period is the time that occurs between the end of one settled pastorate and the beginning of the next. An interim pastor serves a church only during this period, and will not be a candidate for the permanent position. This limitation is the basis for the unique work of the interim pastorate, and it is the responsibility of the interim pastor to maintain the integrity of the position and the work. I. The Interim Minister A. Within the United Church of Christ, interim ministry is understood to be the specialized, time-limited pastoral ministry provided to a local congregation or other ecclesiastical setting during the search process for a person to be called to provide settled ministerial leadership in that setting. The Interim Minister, like other authorized ministers in the United Church of Christ is subject to the oversight of the Association’s Committee on Church and Ministry. -

Global Christian Worship the Sign of the Cross

Global Christian Worship The Sign of the Cross http://globalworship.tumblr.com/post/150428542015/21-things-we-do-when-we-make-the- sign-of-the-cross 21 Things We Do When We Make the Sign of the Cross - for All Christians! Making ‘the sign of the cross’ goes back to the Early Church and belongs to all Christians. It’s a very theologically rich symbolic action! And did you know that Bonhoffer, practically a saint to Protestant Christians, often made the sign of the cross? (See below.) I grew up “thoroughly Protestant” and did not really become aware of “making the sign of the cross” in a thoughtful way until a few years ago, when I joined an Anglican church. Now it’s become a helpful act of devotion for me …. especially after I found this article by Stephen 1 Beale a few years ago (published online in November 2013) at http://catholicexchange.com/21-things-cross There is rich theology embedded in this simple sign, and as a non-Roman Catholic I appreciate all of the symbolism, and it does indeed deepen my spirituality and devotion. The history of making the symbolic motion goes back to the Early Church, more than a millennia before Protestants broke away in the Reformation. So when a Christian act has that long of a history, I believe that I can claim it for myself as a contemporary Christian no matter what denominations use it or don’t use it now. “Around the year 200 in Carthage (modern Tunisia, Africa),Tertullian wrote: ‘We Christians wear out our foreheads with the sign of the cross’ … By the 4th century, the sign of the cross involved other parts of the body beyond the forehead.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sign_of_the_cross So, here is a reposting of Stephen’s list, with additional resources at the end. -

Christian Worship and Cultural Diversity: a Missiological Perspec

Bauer: Christian Worship and Cultural Diversity: A Missiological Perspec Christian Worship and Cultural Diversity: A Missiological Perspective I will begin with a couple of def- initions. First, worship is defined By Bruce L. Bauer as reverence or devotion for a deity, religious homage or venera- tion (Webster’s New World Diction- This article will look at two ary 1984, s.v. “worship”). The vast topics that engender a lot of de- majority of the words for worship bate and disagreement—worship in English Bibles are translated and culture. There are several from the Hebrew word shachah important questions that need to and the Greek word proskuneo. be addressed. How can worship Both words mean to bow down remain biblical and still be cultur- or prostrate oneself before a su- ally relevant? What are some of perior or before God (Seventh-day the biblical principles that should Adventist Bible Dictionary 1979, guide people in all cultures in s.v. “worship”). When I lived in their expression of worship? How Japan people bowed to show re- has American culture dominated spect and the deeper the bow the Adventist worship forms? Why is more respect that was intended. it important to worship God in Bowing in worship is an external culturally relevant ways rather form revealing an inner attitude than having a one size fits all of a desire to show honor. approach to worship? In other Second, culture is defined words, can Adventist worship be as “the more or less integrated expressed in a diversity of ways systems of ideas, feelings, and and still be biblical? values” (Hiebert 1985:30). -

Liturgy and Anglican Identity, Prague, 2005

Liturgy and Anglican Identity A Statement and Study Guide by the International Anglican Liturgical Consultation Prague 2005 Contents: • Overview • Anglican Ethos, Elements, what we value in worship • Some Anglican emphases, trends and aspirations . Bernard Mizeki Anglican Church - South Africa . St Mary’s Anglican Church - England . St Mark’s Anglican Church - Australia . St John’s Anglican Church -Japan • Suggestions for Study Overview We believe that Anglican identity is expressed and formed through our liturgical tradition of corporate worship and private prayer, holding in balance both word and sacramental celebration. Specifically, our tradition is located within the broad and largely western stream of Christian liturgical development but has been influenced by eastern liturgical forms as well. The importance of the eucharist and the pattern of daily prayer were re-focused through the lens of the Reformation, making both accessible to the people of God through simplification of structure and text and the use of vernacular language. Through the exchanges and relationships between the Provinces of the Anglican Communion the legacy of these historic principles continues to inform the on-going revision of our rites and their enactment in the offering to God of our worship. Each Province of the Anglican Communion has its own story to tell, and although within the Communion we are bound together by a common history, what really unites us, as with all Christians, is our one-ness in Christ through baptism and the eucharist. Our unity in baptism and at the table of the Lord is both a gift and a task. We celebrate our unity in Christ and seek to realize that unity through the diversity of backgrounds and cultures within the compass of the world-wide Anglican Communion. -

An Order for the Christian Worship of God for the Inperson Service April

An Order for the Christian Worship of God For the Inperson Service 4th Lesson: John 18:19-24 April 2, 2021 Good Friday Liturgical Color: Purple 5th Lesson: John 18:25-27 6th Lesson: John 18:28-32 A Service of Tenebrea During this powerful service recalling the arrest, trial, and 7th Lesson: John 18:33-38a crucifixion of Jesus Christ, fifteen candles will be lit on the Communion Table. An extended meditation on the Passion of 8th Lesson: John 18:38b-40 Christ will be read. One candle will be extinguished at the conclusion of each reading, until the service concludes in 9th Lesson: John 19:1-11 darkness. Praise Interlude “O Sacred Head Now Wounded” WE GATHER Welcome and Announcements Rev. Alex Stevenson 10th Lesson: John 19:12-16 Prelude “O Sacred Head Now Wounded” Nannette Carnes 11th Lesson: John 19:17-22 The Prayer 12th Lesson: John 19:23-24 Almighty God, your Son Jesus Christ was lifted high upon the cross so that he might draw the whole world to himself. 13th Lesson: John 19:25-27 Grant that we, who glory in this death for our salvation may also glory in his call to take up our cross and follow him; 14th Lesson: John 19:28-30 through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen Anthem “When Jesus Wept” Opening Praise “O Love Divine, What Hast Thou Done” Elizabeth Payton, Cheri King, David King, John Austin King WE HEAR GOD’S WORD AND RESPOND 15th Lesson: John 19:31-37 The Passion of Jesus Christ Tenebrea Service 16th Lesson: John 19:38-42 The service of tenebrae or “darkness” is an ancient Christian form of worship which uses light and darkness to symbolize the death Sealing of the Tomb: of Jesus. -

THE APOSTOLIC AGE Part One: Birth of the Church 1

THE APOSTOLIC AGE 1 Part One: Birth of the Church In this article, we will look at: In studying Church history, we learn about the challenges that our Catholic ancestors faced in every • What is Church history? age as they tried to live their faith and spread it to the • Why study Church history? ends of the earth. • Birth of the Church: Pentecost Day • Persecution of the first Christians As we study Church history, we will encounter saints and villains, Church leaders who inspire us and • Paul Church leaders who scandalize us. Because the Council of Jerusalem • Church is human and made up of imperfect people, it • Formation of the Christian scriptures will sometimes fail us, hurt us and even scandalize • Worship life of early Christians us. But because the Church is divine, it will recover from its failures and grow from strength to strength. What is Church history? Today, the Catholic Church has over one billion members, that is, about 17% of the world’s • Catholic Church history is the story of how the population. community of believers responded to Jesus’ Great Commission to spread his message to the ends of Since we cannot separate the history of the Church the earth (Matt. 28:19-20). from the world where it all occurred, we will touch on the political forces operating during the different • Church history is the story of the people and eras of that period in history. events that have shaped Catholicism since its beginnings in Jerusalem 2,000 years ago. Jesus, Founder of the Church. Catholics believe that Jesus is the founder of the Church.