Report: Inquiry Into Aspects of Bank Mergers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submission Royal Commission Into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry

Submission Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry David Richardson March 2018 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. We barrack for ideas, not political parties or candidates. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. Environmental neglect continues despite heightened ecological awareness. A better balance is urgently needed. The Australia Institute’s directors, staff and supporters represent a broad range of views and priorities. What unites us is a belief that through a combination of research and creativity we can promote new solutions and ways of thinking. OUR PURPOSE – ‘RESEARCH THAT MATTERS’ The Institute publishes research that contributes to a more just, sustainable and peaceful society. Our goal is to gather, interpret and communicate evidence in order to both diagnose the problems we face and propose new solutions to tackle them. The Institute is wholly independent and not affiliated with any other organisation. Donations to its Research Fund are tax deductible for the donor. Anyone wishing to donate can do so via the website at https://www.tai.org.au or by calling the Institute on 02 6130 0530. -

Fees and Charges

Fees and Charges PART 2 – SUPPLEMENTARY PRODUCT DISCLOSURE STATEMENT BANKVIC QANTAS VISA CREDIT CARD September 2020 This Fees and Charges brochure is required to be given by us to members when issuing a financial product to them. It contains details that might reasonably be expected to have a material influence on the decision of a customer as to whether to acquire product. This fees and charges table details those transactions for which a fee or charge is payable when using the BankVic Qantas Visa credit card by you. This also forms part of the Visa credit card Terms and Conditions of Use. This Fees and Charges brochure is current as at 01 September 2020. BANKVIC QANTAS VISA CREDIT CARD ACCOUNT FEES Annual fee Nil Late payment - debited on or after the day when an amount that is $9.00 due for payment is not paid on or before its due date. Card issued in normal course of business Nil Disputed transactions voucher retrieval - fee not charged if transaction $25.00 per transaction found to be merchant error BANKVIC QANTAS REWARDS PROGRAM BankVic Qantas Rewards program Nil TRANSACTIONAL Visa international transaction currency conversion fee 2.00% of the AUD transaction amount1 Visa Cash Advance includes: over the counter (domestic & international) $1.80 per transaction Westpac, St George, Bank SA or Bank of Melbourne ATM withdrawal2 $1.80 per transaction LOST/STOLEN CARDS Replacement in Australia $10.00 Emergency replacement overseas $0 Emergency cash overseas $0 AVOIDING CREDIT CARD FEES To avoid fees ensure that BankVic has received your total payment by the due date as outlined below. -

Australia's Best Banking Methodology Report

Mozo Experts Choice Awards Australia’s Best Banking 2021 This report covers Mozo Experts Choice Australia’s Best Banking Awards for 2021. These awards recognise financial product providers who consistently provide great value across a range of different retail banking products. Throughout the past 12 months, we’ve announced awards for the best value products in home loans, personal loans, bank accounts, savings and term deposit accounts, credit cards, kids’ accounts. In each area we identified the most important features of each product, grouped each product into like-for-like comparisons, and then calculated which are better value than most. The Mozo Experts Choice Australia's Best Banking awards take into account all of the analysis we've done in that period. We look at which banking providers were most successful in taking home Mozo Experts Choice Awards in each of the product areas. But we also assess how well their products ranked against everyone else, even where they didn't necessarily win an award, to ensure that we recognise banking providers who are providing consistent value as well as areas of exceptional value. Product providers don’t pay to be in the running and we don’t play favourites. Our judges base their decision on hard-nosed calculations of value to the consumer, using Mozo’s extensive product database and research capacity. When you see a banking provider proudly displaying a Mozo Experts Choice Awards badge, you know that they are a leader in their field and are worthy of being on your banking shortlist. 1 Mozo Experts Choice Awards Australia’s Best Banking 2021 Australia’s Best Bank Australia’s Best Online Bank Australia's Best Large Mutual Bank Australia's Best Small Mutual Bank Australia’s Best Credit Union Australia’s Best Major Bank 2 About the winners ING has continued to offer Australians a leading range of competitively priced home and personal loans, credit cards and deposits, earning its place as Australia's Best Bank for the third year in a row. -

Westpac Case Study

CEW CASE STUDIES Westpac “CEW’s case study on Westpac is the newest addition to our series devoted to understanding how Australia’s leading organisations are moving closer to gender equality. This is an important resource for anyone who is serious about more women reaching senior leadership roles.” – Diane Smith-Gander, President, Chief Executive Women Who is CEW? To produce this case study, Chief Executive Women undertook 24 detailed interviews with the CEO, members of the Westpac Chief Executive Women is the pre-eminent organisation executive team, members of the Westpac Board, a range of representing Australia’s most senior women leaders from the employees from across the business, members of Chief Executive corporate, public service, academic and not-for-profit sectors. Women (who have been or are members of the Westpac Our vision is women leaders enabling other women leaders. We executive team, senior executives and Board members) as strive to educate and influence all levels of Australian business well as external experts and commentators. CEW has also and government on the importance of gender balance. undertaken a detailed review and independent assessment of We offer innovative and substantive programs to support and the policies, practices and outcomes at Westpac. nurture women’s participation and future leadership. This includes: • Our extensive CEW scholarships program The Leadership Shadow: • CEW’s Leaders Program, a twelve month group coaching In 2013 Chief Executive Women collaborated with the Male program attended by female executives throughout Australia Champions of Change, a group established by Sex Discrimination • CEW thought leadership (including collaborations with Commissioner Elizabeth Broderick made up of CEOs from some partners) and engagement with the business community. -

The World's Most Active Banking Professionals on Social

Oceania's Most Active Banking Professionals on Social - February 2021 Industry at a glance: Why should you care? So, where does your company rank? Position Company Name LinkedIn URL Location Employees on LinkedIn No. Employees Shared (Last 30 Days) % Shared (Last 30 Days) Rank Change 1 Teachers Mutual Bank https://www.linkedin.com/company/285023Australia 451 34 7.54% ▲ 4 2 P&N Bank https://www.linkedin.com/company/2993310Australia 246 18 7.32% ▲ 8 3 Reserve Bank of New Zealand https://www.linkedin.com/company/691462New Zealand 401 29 7.23% ▲ 9 4 Heritage Bank https://www.linkedin.com/company/68461Australia 640 46 7.19% ▲ 9 5 Bendigo Bank https://www.linkedin.com/company/10851946Australia 609 34 5.58% ▼ -4 6 Westpac Institutional Bank https://www.linkedin.com/company/2731362Australia 1,403 73 5.20% ▲ 16 7 Kiwibank https://www.linkedin.com/company/8730New Zealand 1,658 84 5.07% ▲ 10 8 Greater Bank https://www.linkedin.com/company/1111921Australia 621 31 4.99% ▲ 0 9 Heartland Bank https://www.linkedin.com/company/2791687New Zealand 362 18 4.97% ▼ -6 10 ME Bank https://www.linkedin.com/company/927944Australia 1,241 61 4.92% ▲ 1 11 Beyond Bank Australia https://www.linkedin.com/company/141977Australia 468 22 4.70% ▼ -2 12 Bank of New Zealand https://www.linkedin.com/company/7841New Zealand 4,733 216 4.56% ▼ -10 13 ING Australia https://www.linkedin.com/company/387202Australia 1,319 59 4.47% ▲ 16 14 Credit Union Australia https://www.linkedin.com/company/784868Australia 952 42 4.41% ▼ -7 15 Westpac https://www.linkedin.com/company/3597Australia -

Global Currency Card Funds Redemption Form

Global Currency Card Funds Redemption Form. Complete this form to transfer any remaining balances from your closed Global Currency Card account to a nominated account. Funds Redemption Details. To transfer any remaining funds, provide your Global Currency Card information and Australian bank account details below. Please note, any remaining funds will be paid to you in Australian Dollars (AUD) within 20 business days of receipt of this form. First name: Suburb: Postcode: Middle name: Mobile: Surname: Last 4 digits of your card number: Date of birth: / / Destination BSB: Scan a signed and completed copy of this form to: Bank of Melbourne Global Currency Card Service Centre PO Box 3845 Destination account number: RHODES NSW 2138 Or fax to + 61 1300 781 289 Questions? Please call 1300 804 266 in Australia or +61 3 8536 7873 when travelling for 24/7 support. I authorise Bank of Melbourne to transfer the Available Balance of my Global Currency Card account less any outstanding transactions, fees or amounts owed by me, in accordance with the account details provided by me. Signature Date ✗ / / Internal use only Residual value AUD: Authoriser name: Authoriser signature ✗ The details: Bank of Melbourne Global Currency Card is issued by Cuscal Limited ACN 087 822 455 AFSL 244116 (Cuscal). Cuscal is an authorised deposit taking institution and a member of Visa International and does not take deposits from you. Westpac Banking Corporation is the distributor of the product and is not responsible for and does not guarantee the product or card or your ability to access any prepaid value or the use of the product or card. -

The Wallis Report and Implications of Bank Mergers for Efficiencies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Faculty of Business and Law SCHOOL OF ACCOUNTING, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE School Working Paper - Economic Series 2006 SWP 2006/12 The Wallis Report and Implications of Bank Mergers for Efficiencies Author: Su Wu The working papers are a series of manuscripts in their draft form. Please do not quote without obtaining the author’s consent as these works are in their draft form. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and not necessarily endorsed by the School. The Wallis Report and Implications of Bank Mergers for Efficiencies Author: Su Wu Affiliation: School of Accounting, Economics and Finance, Deakin University, Australia Address: 221 Burwood Hwy, Burwood, Vic 3125, Australia Email: [email protected] Phone: 61-3-92517808 Abstract: This paper examines the competitive consequences of bank mergers and acquisitions with particular reference to the Wallis Inquiry into the Australian Financial System in 1996. The Government responded by adopting a four pillars policy preventing mergers among the four major banks. Using the super-efficiency data envelopment analysis model, the technical efficiencies of banks operating in Australia over the period from 1983 to 2001 are estimated. Two separate methods are employed to evaluate the characteristics and determinants of merger and acquisition activities in the sector. The first method examines economic performance of banks involved in merger activities. A second method is also used to determine program efficiency differences between banks of different entry types after adjusting for differences in intra-group managerial inefficiency. -

Financial Report Annual Financial Report 1999 Form 20F Cross Reference Index 2

Westpac Australia’s First Bank Official Partner Official Bank of the 2000 Sydney 2000 Olympic Games Paralympic Games 1999 Annual Financial Report Annual Financial Report 1999 Form 20F cross reference index 2 Description of business 3 Financial review 9 Selected consolidated financial and operating data 10 Management’s discussion and analysis of financial condition and results of operations 14 Overview of performance 14 Profit and loss review 15 Balance sheet review 18 Business group results 19 Risk management within Westpac 22 Board of Directors 30 Corporate governance 32 Directors’ report 35 Five year summary 44 Financial report 45 Shareholding information 118 In this report references to ‘Westpac’, ‘we’, ‘us’ and ‘our’ are to Westpac Banking Corporation. References to ‘Westpac’, ‘we’, ‘us’ and ‘our’ under the captions ‘Description of business’, ‘Financial review’ and ‘Shareholding information’ include Westpac and its consolidated subsidiaries unless they clearly mean just Westpac Banking Corporation. We are providing our report to shareholders in two parts: • a Concise Annual Report • an Annual Financial Report Both parts will be lodged with the Australian Stock Exchange Limited (ASX) and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and are available on www.westpac.com.au The Annual Financial Report includes the disclosure requirements for both Australia and the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). It will be lodged with the SEC as an Annual Report on form 20F. Westpac Banking Corporation ARBN 007 457 141 1 Form 20F cross reference index (for the purpose of filing with the US SEC) 20-F item number and caption Page Currency of presentation, exchange rates and certain definitions 126 Part I Item 1. -

Home Loan Redraw Request Form

Redraw Request Form – Residential Home Loans Note to (1) Redraw is not available for Super Fund Home Loans, Senior Access Home Loans, Senior Access Plus Home Loans and Money borrower(s): For Livings Loans. (2) For variable rate loans, amounts which you have prepaid under your agreement less than a month before a monthly repayment date cannot be redrawn until after that monthly repayment date has passed and the amount redrawn does not result in the balance owing on your loan account exceeding the amount which would be owing if you had paid all scheduled repayments on time. (3) For fixed rate loans, redraw is only available for loans fixed on and after 30 November 2009 and only for excess funds paid into the loan during the current fixed rate period up to the value of the prepayment threshold. (4) Please complete (i) all questions, (ii) use a black pen, AND (iii) use CAPITAL LETTERS. (5) All Borrowers on your loan account must sign. (6) The Bank does not promise it will relend you the redraw amount. This request is subject to its consent. (7) You should obtain your own tax advice in relation to the redraw. (8) The Bank only accepts this request by lending the redraw amount. The Bank is not treated as accepting the request in any other circumstances. (9) Redraw requests up to $30,000 made in a branch can be processed immediately. The processing of other redraw requests using this form will take approximately five working days. Our privacy policy is available at bankofmelbourne.com.au or by calling Date Loan account number 13 22 66 and covers how we handle your / / personal information. -

Westpac Banking Corporation September 2017

Productivity Commission Inquiry into Competition in the Australian Financial System. Westpac Banking Corporation September 2017 Note: In this submission, a reference to ‘Westpac’, ‘Group’, ‘Westpac Group’, ‘we’, ‘us’, and ‘our’ is a reference to Westpac Banking Corporation ABN 33 007 457 141 and its subsidiaries, unless it clearly means just Westpac Banking Corporation. Table of contents Executive summary 2 Section 1 – The Nature of Competition in the Australian Financial System 5 1.1 Introduction 5 1.2 Market Structure 8 1.3 Business models 11 1.4 Key indicators of competition 13 1.5 Profitability over the cycle 15 1.6 The funding profile of the banking system 18 Section 2 – Supervision and regulation 22 2.1 Introduction 22 2.2 Competition and regulation 24 2.3 Regulatory steps to encourage competition and innovation 25 Section 3 – Facilitating beneficial customer outcomes 26 3.1 Investment in innovation and service 26 3.2 New entrants and disrupters 28 3.3 Open data’s role in competition 30 3.4 Supporting customer flexibility and choice 31 3.5 Innovations in payments 33 3.6 Disclosure and transparency 34 3.7 Financial inclusion 35 Section 4 – Competitive dynamics within particular segments 36 4.1 Residential mortgages 36 4.2 Credit cards 40 4.3 Customer deposits 45 4.4 Banking for SMEs 46 4.5 Wealth management and insurance 51 Conclusion 56 Inquiry into Competition in the Australian Financial System | Westpac Banking Corporation 1 Executive summary Australia’s financial system is strong, competitive and well-regulated. However, Westpac will always support changes that further improve competition, enhance customer choice, and ultimately promote better consumer outcomes. -

Customer Identification Form (CIF)

Customer Identification Form (CIF) Information Required Individual Customers must complete section 1, 3 and 4 Sole Traders must complete sections 1, 2, 3 and 4 CIS No. (if known) Account number (if known) Account Name Section 1 Details of Individual to Individual (name in full) Date of birth Gender be identified (Individual Customers and Sole Are you known by any other name(s)? If yes, please specify all names (use a separate sheet if required) Traders) Yes No Residential address (PO Box not allowed) Employment Type: Please select the employment type that reflects your current situation best. Casual Other Social Security Recipient Dependant Contractor Part Time Student Full Time Retired Temporary Independent Contractor Self Employed Unemployed Occupation Purpose of business relationship: This refers to your reasons for engaging with us to obtain products and services. Customers may have multiple reasons for dealing with us. Please indicate all of these reasons below. Transactional Long Term Borrowing Financial Markets Savings Protection Correspondent Banking Short Term Borrowing Wealth Additional information (please specify) Source of Funds: This refers to the origin of the funds that are the subject of the business relationship between you and us. Please note that many customers have multiple sources of funds. Please indicate all sources of funds below. Salary/Wages Superannuation/Pension Redundancy Commission Loan Inheritance Bonus Insurance payment Gift/Donation Business income/earnings Compensation payment Windfall Business profits Government benefits Tax refund Investment income/earnings Sale of assets Additional Sources (please specify) Rental income Liquidation of assets © Bank of Melbourne – A Division of Westpac Banking Corporation ABN 33 007 457 141 AFSL and Australian credit licence 233714. -

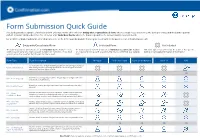

Form Submission Quick Guide This Guide Provides a Sample of Banks and Form Offerings

Form Submission Quick Guide This guide provides a sample of banks and form offerings. Banks offer either an Entity wide / Consolidated form, where a single request is sent to the bank per entity, and the bank responds with all accounts and products for that entity; or offer Individual Forms where the bank responds to the account number provided only. For a full list of banks and forms offered, please refer to the In Network Responder Report generated from the Reports section in Confirmation.com. Entity wide/Consolidated Form Individual Form Not Included The bank responds to form details on an entity wide basis. Auditors send a The bank responds to form details on an individual account basis. Auditors This form type is not offered by the bank as the specific single request using one main account number for reference. If no main are required to set up each account number to be confirmed as a separate bank does not supply information in this manner. account exists the customer identification number is used. form. Form Type Form Description Westpac St George Bank Bank of Melbourne Bank SA NAB For each form sent, the bank will then provide an extensive report of all your Client Consolidated bank dealings for the legal entity specified. No other form types should be submitted if this form option is used. OR An asset account is typically a current, cheque, deposit, savings, investment AU – Asset (Deposit) and any other credit balance. A liability account is typically a bank loans, term loans and any other debit AU – Liability (Loan) balances.