State V. Richardson (Super

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASCLD Crime Lab Minute April 30, 2018

ASCLD Crime Lab Minute April 30, 2018 Dear Colleagues, This year has been a very busy one for our Board of Directors. We are anxious to see you all in Atlanta so we can meet personally to share our progress and discuss challenges and direction for this upcoming year. In addition to the information posted this last week (Membership Candidates, Board Candidates and Bylaw changes), we have additional information to share to keep you up to speed with the rapidly evolving field of forensics. Our meeting is that opportunity to have everything forensic brought to you for one stop shopping under one roof. If that sounds like a bit of a sales pitch, it is. Our planning committee has done an extraordinary job this year so we are very exciting about what will prove to be an outstanding meeting. Our Board has approved several new administrative documents we feel will add to our arsenal of resources found on the ASCLD webpage. These new or revised documents include a Code of Professional Responsibility Model Policy, a Statement of Principles, an updated Code of Ethics including a mechanism to make an ethics complaint including a fillable Complaint Form, and an update to our Guidelines for Forensic Laboratory Management. We are very proud of the work that has been done to create and update these new documents, so please check them out. Fillable complaint form https://www.ascld.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Fillable-Complaint- form.pdf Code of Ethics https://www.ascld.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Code-of-Ethics.pdf Statement of Principles https://www.ascld.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/ASCLD-STATEMENT- OF-PRINCIPLES.pdf Model Policy – Code of Professional Responsibility https://www.ascld.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/ASCLD-MODEL- POLICY_ProfResponsibility.pdf We take our representation of your labs and our field very seriously, so we deeply value your opinion and input. -

Conflicts of Interest Between Death Investigators and Prosecutors

American University Washington College of Law Washington College of Law Research Paper No. 2019- A DEADLY PAIR: CONFLICTS OF INTEREST BETWEEN DEATH INVESTIGATORS AND PROSECUTORS Ira P. Robbins This paper can be downloaded without charge from The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3329559 A Deadly Pair: Conflicts of Interest Between Death Investigators and Prosecutors IRA P. ROBBINS* As an inevitable fact of life, death is a mysterious specter looming over us as we move through the world. It consumes our literature, religions, and social dialogues—the death of a prominent figure can change policies and perceptions about our approaches to many problems. Given death’s significance, it is reasonable to try to understand causes of death generally, as well as on a case-by-case basis. While scholars and mourners attempt to answer the philosophical questions about death, the practical and technical questions are typically answered by death investigators. Death investigators attempt to decipher the circumstances surrounding suspicious and unexplained deaths to provide solace to family members and information to law enforcement services to help them determine whether further investigative steps are necessary. But while the answers provided by death investigators may provide some direction, in many ways the death investigation system actually inhibits the pursuit of justice. The current death investigation system creates conflicts of interest between death investigators and prosecutors. Death investigators and prosecutors are often organized under the same governmental structure or even within the same offices. This close association between the two systems results in patterns of relationships that disadvantage defense teams and prevent equal access to death investigation resources. -

IN the SUPREME COURT of MISSISSIPPI NO. 2018-CA-01586-SCT EDDIE LEE HOWARD, JR. V. STATE of MISSISSIPPI DATE of JUDGMENT

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI NO. 2018-CA-01586-SCT EDDIE LEE HOWARD, JR. v. STATE OF MISSISSIPPI DATE OF JUDGMENT: 10/10/2018 TRIAL JUDGE: HON. LEE J. HOWARD TRIAL COURT ATTORNEYS: LOUWLYNN VANZETTA WILLIAMS ROBERT M. RYAN WILLIAM TUCKER CARRINGTON WILLIAM McLEOD McINTOSH VANESSA POTKIN M. CHRIS FABRICANT PETER J. NEUFELD JASON L. DAVIS BRAD ALAN SMITH COURT FROM WHICH APPEALED: LOWNDES COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT ATTORNEY FOR APPELLANT: WILLIAM TUCKER CARRINGTON ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEE: OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL BY: ASHLEY LAUREN SULSER LADONNA C. HOLLAND LYNN FITCH CANDICE LEIGH RUCKER NATURE OF THE CASE: CIVIL-POST-CONVICTION RELIEF DISPOSITION: REVERSED, RENDERED, AND REMANDED - 08/27/2020 MOTION FOR REHEARING FILED: MANDATE ISSUED: EN BANC. ISHEE, JUSTICE, FOR THE COURT: ¶1. Eddie Howard was sentenced to death for the rape and murder of eighty-four-year-old Georgia Kemp. Howard was tied to the crime by Dr. Michael West, who identified Howard as the source of bite marks on Kemp’s body. At trial, Dr. West testified that he was a member of the American Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO) and that he had followed its guidelines in rendering his opinion. But since Howard’s trial, the ABFO has revised those guidelines to prohibit such testimony, and this reflects a new scientific understanding that an individual perpetrator cannot be reliably identified through bite-mark comparison. This, along with new DNA testing and the paucity of other evidence linking Howard to the murder, requires the Court to conclude that Howard is entitled to a new trial. We reverse the trial court’s denial of postconviction relief and vacate Howard’s conviction and sentence. -

1 VALENA ELIZABETH BEETY Professor, West Virginia University

VALENA ELIZABETH BEETY Professor, West Virginia University College of Law, P.O. Box 6130, Morgantown, WV 26501 [email protected] (304) 293-7520 EDUCATION University of Chicago Law School, J.D. 2006 Staff Member, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LAW REVIEW Fellow, University of Chicago Law School Stonewall Fellowship Fellow, The Alfred B. Teton Civil and Human Rights Scholarship University of Chicago, the College, B.A., Anthropology, with Honors 2002 Richter Grant for Undergraduate Research, Chicago Legal Aid for Incarcerated Mothers Metcalf Fellow, Governor’s Commission on the Status of Women in Illinois Fulbright/IIE Teacher, Lycee Darchicourt, Henin-Beaumont, France ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE West Virginia University Professor of Law (tenured) 2017 – present Adjunct Professor of Forensic & Investigative Sciences 2017 – 2020 Associate Professor of Law 2012 – 2017 Director of the West Virginia Innocence Project 2012 – present Deputy Director of the Clinical Law Program 2012 – 2017 Founder and Co-Director Appalachian Justice Initiative 2016 – present Founder and Co-Director LL.M. in Forensic Justice Online 2013 – 2016 Founder University of Chicago-WVU Franklin Cleckley Fellowship 2013 – present Courses: Criminal Procedure I, Post-Conviction Remedies, Forensic Justice Seminar, Forensic Justice Online, Innocence Clinic University of Colorado Law School Visiting Scholar Spring 2015 University of Texas School of Law Big XII Faculty Fellow October 2013 University of Mississippi School of Law Senior Staff Attorney, Innocence Project 2009 – 2012 Adjunct Professor of Law 2010 – 2012 Courses: Identity and Criminality, Civil Rights and Prisons, Innocence Clinic CLERKSHIPS The Honorable Martha Craig Daughtrey, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit 2007 – 2008 The Honorable Chief Judge James G. -

VALENA ELIZABETH BEETY West Virginia University College of Law P.O

VALENA ELIZABETH BEETY West Virginia University College of Law P.O. Box 6130, Morgantown, WV 26501 [email protected] Office: (304) 293-7520 ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE West Virginia University College of Law, Morgantown, West Virginia Associate Professor of Law, 2012 – Present Deputy Director of the Clinical Law Program; Chair of the West Virginia Innocence Project Creator and Director: LL.M. in Forensic Justice University of Chicago-WVU Franklin D. Cleckley Fellowship Courses: Criminal Procedure I, Post-Conviction Remedies, Innocence Clinic Faculty Advisor: StreetLaw, ACLU Law School Chapter University of Colorado Law School, Boulder, CO Visiting Scholar, Spring 2015 University of Texas School of Law, Austin, TX Big XII Faculty Fellow, October - November 2013 University of Mississippi School of Law, University, Mississippi Senior Staff Attorney, Mississippi Innocence Project, 2009 – 2012 Adjunct Professor of Law, 2010 – 2012 Courses: Identity and Criminality, Civil Rights and Prisons, Innocence Clinic Faculty Advisor: Reproductive Justice Dinner Club, Law Students for Reproductive Justice JUDICIAL CLERKSHIPS The Honorable Martha Craig Daughtrey, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit Law Clerk, 2007 – 2008 The Honorable Chief Judge James G. Carr, U.S. District Court, Northern District of Ohio Law Clerk, 2006 – 2007 EDUCATION University of Chicago Law School, J.D., 2006. Staff Member, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LAW REVIEW President, ACLU Law School Chapter Co-Founder, Student Advocates for Marriage Equality Student Lawyer, Mandel Legal Aid Clinic, Juvenile and Criminal Justice Project Fellow, University of Chicago Law School Stonewall Fellowship Fellow, The Alfred B. Teton Civil and Human Rights Scholarship PILS Public Interest Award 2004, 2005, 2006, Top Student University of Chicago, the College, B.A., Anthropology, with Honors, 2002. -

National Association of Medical Examiners, Executive Committee, July 2, 2009

Suprems Court, U.S. FILED No. 13-735 JAN\ 1 201't OFPICE OF THE CLERK Jn tltbt &upreme ~ourt of tbe Wniteb &tate~ --------·-------- EFREN MEDINA, Petitioner, v. ARIZONA, Respondent. --------·-------- On Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The Supreme Court Of Arizona --------·-------- BRIEF OF THE INNOCENCE NETWORK AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER --------·-------- STEPHEN A. MILLER Counsel of Record BRIAN KINT COZEN O'CONNOR 1900 Market Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 (215) 665-2000 [email protected] BARRY C. SCHECK M. CHRIS FABRICANT PETER MORENO INNOCENCE NETWORK, INC. 100 Fifth Avenue, 3rd Floor New York, NY 10011 (212) 364-5340 COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS 18001225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM BLANK PAGE 1 CAPITAL CASE QUESTION PRESENTED Amicus Curiae adopts and incorporates the ques tion presented by Petitioner. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE...................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.............................. 3 ARGUMENT........................................................ 5 I. THE CURRENT SYSTEM IMPORTS FLAWED, TESTIMONIAL STATEMENTS INTO AUTOPSY REPORTS ....................... 5 A. The contents of autopsy reports are inherently testimonial......................... 5 B. The current death investigation sys tem undermines the veracity of au topsy reports........................................ 6 (1) Dr. Thomas Gill . 8 (2) Dr. Stephen Hayne . 9 (3) Ralph Erdmann.............................. 11 C. Forensic pathology is particularly susceptible to cognitive bias and sug gestion by law enforcement................. 11 II. CONFRONTATION OF THE AUTHORS OF FLAWED TESTIMONIAL STATE MENTS IN AUTOPSY REPORTS SERVES THE INTERESTS OF JUSTICE .................. 18 A. Surrogate testimony allows law en forcement officials to cover up cogni tive bias and forensic fraud................. 18 B. Errors concerning the time, manner, and cause of death are major factors in wrongful convictions . -

Death Penalty Hits Historic Lows Despite Federal Execution Spree Pandemic, Racial Justice Movement Fuel Continuing Death Penalty Decline

The Death Penalty in 2020: Year End Report Death Penalty Hits Historic Lows Despite Federal Execution Spree Pandemic, Racial Justice Movement Fuel Continuing Death Penalty Decline DEATH SENTENCES BY YEAR 3 Key Findings Peak: 315 in 1996 3 • Colorado becomes nd 22 state to abolish 2 death penalty 2 • Reform prosecutors gain footholds in 1 formerly heavy-use 1 death penalty counties 297 50 • Fewest new death 18 in 2020 sentences in modern 0 1973 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 era; state executions lowest in 37 years EXECUTIONS BY YEAR • Federal government 1 resumes executions Peak: 98 in 1999 with outlier practices, for first time ever 80 conducts more executions than all 60 states combined • COVID-19 pandemic 40 halts many 81 executions and court 2 proceedings; federal 17 in 2020 executions spark 0 1977 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 outbreaks The Death Penalty in 2020: Year End Report Introduction Death Row by State State 2020† 2019† 2020 was abnormal in almost every way, and that was clearly the case when it came to capital punishment in the United States. The California 724 729 interplay of four forces shaped the U.S. death penalty landscape in Florida 346 348 2020: the nation’s long - term trend away from capital punishment; the Texas 214 224 worst global pandemic in more than a century; nationwide protests Alabama 172 177 for racial justice; and the historically aberrant conduct of the federal North Carolina 145 144 administration. At the end of the year, more states had abolished the Pennsylvania 142 154 death penalty or gone ten years without an execution, more counties Ohio 141 140 had elected reform prosecutors who pledged never to seek the death Arizona 119 122 penalty or to use it more sparingly; fewer new death sentences were Nevada 71 74 imposed than in any prior year since the Supreme Court struck down Louisiana 69 69 U.S. -

MD Program.Fm

Doctor of Medicine Program 24 Doctor of Medicine Program Mission Statement and the Medical Curriculum The mission of the Duke University School of Medicine is: To prepare students for excellence by first assuring the demonstration of defined core competencies. To complement the core curriculum with educational opportunities and advice regarding career planning which facilitates students to diversify their careers, from the physician-scientist to the primary care physician. To develop leaders for the twenty-first century in the research, education, and clinical practice of medicine. To develop and support educational programs and select and size a student body such that every student participates in a quality and relevant educational experi- ence. Physicians are facing profound changes in the need for understanding health, dis- ease, and the delivery of medical care changes which shape the vision of the medical school. These changes include: a broader scientific base for medical practice; a national crisis in the cost of health care; an increased number of career options for physicians yet the need for more generalists; an emphasis on career-long learning in investigative and clinical medicine; the necessity that physicians work cooperatively and effectively as leaders among other health care professionals; and the emergence of ethical issues not heretofore encountered by physicians. Medical educators must prepare physicians to respond to these changes.The most successful medical schools will position their stu- dents to take the lead addressing national health needs. Duke University School of Med- icine is prepared to meet this challenge by educating outstanding practitioners, physician scientists, and leaders. Continuing at the forefront of medical education requires more than educating Duke students in basic science, clinical research, and clinical programs for meeting the health care needs of society. -

Redacted Redacted Redacted Redacted Redacted Redacted1

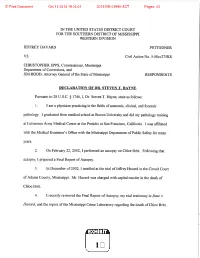

E-Filed Document Oct 13 2014 19:24:01 2013-DR-01995-SCT Pages: 43 Redacted Redacted Redacted Redacted Redacted Redacted1 Deposition of Dr. Steven Hayne Page 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI WESTERN DIVISION JEFFREY HAVARD PETITIONER VS. CIVIL ACTION NO. 5:08-CV-275-KS CHRISTOPHER EPPS, et al. RESPONDENTS ********** DEPOSITION OF DR. STEVEN HAYNE Taken at the offices of Watkins & Eager, 400 East Capitol Street, Jackson, Mississippi, on Tuesday, November 23, 2010, beginning at approximately 8:57 a.m. ******** APPEARANCES NOTED HEREIN CATHY M. WHITE, CSR NO. 1309 Redacted PROFESSIONAL COURT REPORTING, LLC 2 Post Office Box 320928 Jackson, Mississippi 39232-0928 Redacted (601) 919-8662 Redacted Redacted Professional CourtRedacted Reporting, LLC 601.919.8662Redacted Redacted Redacted Deposition of Dr. Steven Hayne 2 (Pages 2 to 5) Page 2 Page 4 1 APPEARANCES 1 MR. MAGEE: Good morning. This is the 2 2 videotaped deposition of Dr. Steven Hayne taken by 3 MARK JICKA, ESQUIRE [email protected] 3 counsel in the matter of Jeffrey Havard versus 4 Watkins & Eager 4 Christopher Epps, et al., in the District Court of the 400 East Capitol Street, Suite 300 5 Southern District of Mississippi, Western Division. 5 Jackson, Mississippi 39201 6 GRAHAM P. CARNER, ESQUIRE 6 Today's date is November 23rd, 2010. The time is [email protected] 7 approximately 8:57 a.m. Counsel may now introduce 7 The Gilliam Firm 8 themselves on record. 606 Highway 80 West, Suite D 8 Clinton, Mississippi 39056 9 MR. JICKA: I am Mark Jicka, and I represent 9 COUNSEL FOR PETITIONER 10 Jeffrey Havard. -

Modern Pathology

VOLUME 32 | SUPPLEMENT 2 | MARCH 2019 MODERN PATHOLOGY 2019 ABSTRACTS QUALITY ASSURANCE (1897-1977) MARCH 16-21, 2019 PLATF OR M & 2 01 9 ABSTRACTS P OSTER PRESENTATI ONS EDUCATI ON C O M MITTEE Jason L. Hornick , C h air Ja mes R. Cook R h o n d a K. Y a nti s s, Chair, Abstract Revie w Board S ar a h M. Dr y and Assign ment Co m mittee Willi a m C. F a q ui n Laura W. La mps , Chair, C ME Subco m mittee C ar ol F. F ar v er St e v e n D. Billi n g s , Interactive Microscopy Subco m mittee Y uri F e d ori w Shree G. Shar ma , Infor matics Subco m mittee Meera R. Ha meed R aj a R. S e et h al a , Short Course Coordinator Mi c h ell e S. Hir s c h Il a n W ei nr e b , Subco m mittee for Unique Live Course Offerings Laksh mi Priya Kunju D a vi d B. K a mi n s k y ( Ex- Of ici o) A n n a M ari e M ulli g a n Aleodor ( Doru) Andea Ri s h P ai Zubair Baloch Vi nita Parkas h Olca Bast urk A nil P ar w a ni Gregory R. Bean , Pat h ol o gist-i n- Trai ni n g D e e p a P atil D a ni el J. Br at K wun Wah Wen , Pat h ol o gist-i n- Trai ni n g Ashley M. -

Doctor of Medicine Program

Doctor of Medicine Program Mission Statement and the Medical Curriculum The mission of the Duke University School of Medicine is: To prepare students for excellence by first assuring the demonstration of defined core competencies. To complement the core curriculum with educational opportunities and advice regarding career planning which facilitates students to diversify their careers, from the physician-scientist to the primary care physician. To develop leaders for the twenty-first century in the research, education, and clinical practice of medicine. To develop and support educational programs and select and size a student body such that every student participates in a quality and relevant educational experience. Physicians are facing profound changes in the need for understanding health, dis- ease, and the delivery of medical care changes which shape the vision of the medical school. These changes include: a broader scientific base for medical practice; a national crisis in the cost of health care; an increased number of career options for physicians yet the need for more generalists; an emphasis on career-long learning in investigative and clinical medicine; the necessity that physicians work cooperatively and effectively as leaders among other health care professionals; and the emergence of ethical issues not heretofore encountered by physicians. Medical educators must prepare physicians to respond to these changes.The most successful medical schools will position their stu- dents to take the lead addressing national health needs. Duke University School of Med- icine is prepared to meet this challenge by educating outstanding practitioners, physician scientists, and leaders. Continuing at the forefront of medical education requires more than educating Duke students in basic science, clinical research, and clinical programs for meeting the health care needs of society. -

EDDIE LEE HOWARD, JR. V. STATE of MISSISSIPPI

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI NO. 2018-CA-01586-SCT EDDIE LEE HOWARD, JR. v. STATE OF MISSISSIPPI DATE OF JUDGMENT: 10/10/2018 TRIAL JUDGE: HON. LEE J. HOWARD TRIAL COURT ATTORNEYS: LOUWLYNN VANZETTA WILLIAMS ROBERT M. RYAN WILLIAM TUCKER CARRINGTON WILLIAM McLEOD McINTOSH VANESSA POTKIN M. CHRIS FABRICANT PETER J. NEUFELD JASON L. DAVIS BRAD ALAN SMITH COURT FROM WHICH APPEALED: LOWNDES COUNTY CIRCUIT COURT ATTORNEY FOR APPELLANT: WILLIAM TUCKER CARRINGTON ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEE: OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL BY: ASHLEY LAUREN SULSER LADONNA C. HOLLAND LYNN FITCH CANDICE LEIGH RUCKER NATURE OF THE CASE: CIVIL-POST-CONVICTION RELIEF DISPOSITION: REVERSED, RENDERED, AND REMANDED - 08/27/2020 MOTION FOR REHEARING FILED: MANDATE ISSUED: EN BANC. ISHEE, JUSTICE, FOR THE COURT: ¶1. Eddie Howard was sentenced to death for the rape and murder of eighty-four-year-old Georgia Kemp. Howard was tied to the crime by Dr. Michael West, who identified Howard as the source of bite marks on Kemp’s body. At trial, Dr. West testified that he was a member of the American Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO) and that he had followed its guidelines in rendering his opinion. But since Howard’s trial, the ABFO has revised those guidelines to prohibit such testimony, and this reflects a new scientific understanding that an individual perpetrator cannot be reliably identified through bite-mark comparison. This, along with new DNA testing and the paucity of other evidence linking Howard to the murder, requires the Court to conclude that Howard is entitled to a new trial. We reverse the trial court’s denial of postconviction relief and vacate Howard’s conviction and sentence.