Biological Opinion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Mitigation Plan

Flood Mitigation Plan (June 2008) CITY OF NOVATO FLOOD MITIGATION PLAN CITY OF NOVATO FLOOD MITIGATION PLAN ........................................................ 2 SECTION I - PLANNING PROCESS ......................................................................... 17 Part 1 - Process Organization .................................................................................................................................... 17 Planning Process Documentation ............................................................................................................................. 17 Jurisdictional Participation ........................................................................................................................................ 17 Process Description ................................................................................................................................................... 18 Part 2 - Public Outreach ............................................................................................................................................. 22 Flood Mitigation Planning Committee .................................................................................................................... 22 Public Participation Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 48 Results and Recommendations from Community & Stakeholders ........................................................................ 48 -

(Oncorhynchus Mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California

Historical Distribution and Current Status of Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California Robert A. Leidy, Environmental Protection Agency, San Francisco, CA Gordon S. Becker, Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA Brett N. Harvey, John Muir Institute of the Environment, University of California, Davis, CA This report should be cited as: Leidy, R.A., G.S. Becker, B.N. Harvey. 2005. Historical distribution and current status of steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward p. 3 Introduction p. 5 Methods p. 7 Determining Historical Distribution and Current Status; Information Presented in the Report; Table Headings and Terms Defined; Mapping Methods Contra Costa County p. 13 Marsh Creek Watershed; Mt. Diablo Creek Watershed; Walnut Creek Watershed; Rodeo Creek Watershed; Refugio Creek Watershed; Pinole Creek Watershed; Garrity Creek Watershed; San Pablo Creek Watershed; Wildcat Creek Watershed; Cerrito Creek Watershed Contra Costa County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 39 Alameda County p. 45 Codornices Creek Watershed; Strawberry Creek Watershed; Temescal Creek Watershed; Glen Echo Creek Watershed; Sausal Creek Watershed; Peralta Creek Watershed; Lion Creek Watershed; Arroyo Viejo Watershed; San Leandro Creek Watershed; San Lorenzo Creek Watershed; Alameda Creek Watershed; Laguna Creek (Arroyo de la Laguna) Watershed Alameda County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 91 Santa Clara County p. 97 Coyote Creek Watershed; Guadalupe River Watershed; San Tomas Aquino Creek/Saratoga Creek Watershed; Calabazas Creek Watershed; Stevens Creek Watershed; Permanente Creek Watershed; Adobe Creek Watershed; Matadero Creek/Barron Creek Watershed Santa Clara County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. -

Salmon and Steelhead in Your Creek: Restoration and Management of Anadromous Fish in Bay Area Watersheds

Salmon and Steelhead in Your Creek: Restoration and Management of Anadromous Fish in Bay Area Watersheds Presentation Summaries (in order of appearance) Gary Stern, National Marine Fisheries Service Steelhead as Threatened Species: The Status of the Central Coast Evolutionarily Significant Unit Under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA), a "species" is defined to include "any distinct population segment of any species of vertebrate fish or wildlife which interbreeds when mature." To assist NMFS apply this definition of "species to Pacific salmon stocks, an interim policy established the use of "evolutionarily significant unit (ESU) of the biological species. A population must satisfy two criteria to be considered an ESU: (1) it must be reproductively isolated from other conspecific population units; and (2) it must represent an important component in the evolutionary legacy of the biological species. The listing of steelhead as "threatened" in the California Central Coast resulted from a petition filed in February 1994. In response to the petition, NMFS conducted a West Coast-wide status review to identify all steelhead ESU’s in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and California. There were two tiers to the review: (1) regional expertise was used to determine the status of all streams with regard to steelhead; and (2) a biological review team was assembled to review the regional team's data. Evidence used in this process included data on precipitation, annual hydrographs, monthly peak flows, water temperatures, native freshwater fauna, major vegetation types, ocean upwelling, and smolt and adult out-migration (i.e., size, age and time of migration). Steelhead within San Francisco Bay tributaries are included in the Central California Coast ESU. -

Environmental Assessment for Partial Funding for the Sears Point Restoration Project

Environmental Assessment For Partial Funding for the Sears Point Restoration Project September 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose and Need 1.2 Public Participation 1.3 Organization of this EA 2.0 PROPOSED ACTION 2.1 Alternatives Considered 3.0 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT 3.1 Protected and Special-Status Species 3.1.1 Special Status Wildlife 3.1.2 Special Status Fish 3.2.3 Special Status Plants 3.2 Climate 4.0 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS 4.1.1 Special Status Wildlife 4.1.2 Special Status Fish 4.1.3 Special Status Plants 4.2.1 Climate 5.0 MITIGATION MEASURES AND MONITORING 6.0 CUMULATIVE AND INDIRECT IMPACTS 6.1 Baseline Conditions for Cumulative Impacts Analysis 6.2 Past, Present, and Reasonably Foreseeable Future Actions 6.3 Resources Discussed and Geographic Study Areas 6.4 Approach to Cumulative Impact Analysis 7.0 AGENCY CONSULTATIONS 2 I. Executive Summary Ducks Unlimited requested funding through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Community-based Restoration Program (CRP) for restoration of a 960 acre site that is part of Sears Point Wetlands and Watershed Restoration Project . The Sonoma Land Trust (SLT), a non-profit organization, purchased the 2,327-acre properties collectively known as Sears Point in 2004 and 2005, and is the recipient of a number of grants for its restoration. In April of 2012, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the STL and the California Department of Fish and Game published a final Sears Point Wetland and Watershed Restoration Project Environmental Impact Report (SPWWRP) / Environmental Impact Statement that assess the environmental impacts of restoration of Sears Point (State Clearinghouse #2007102037). -

12 Hydrology, Flooding and Water Quality

12 HYDROLOGY, FLOODING AND WATER QUALITY This chapter describes local and regional hydrology, flooding and water quality in and around Novato, as well as the applicable federal, State and local regulations. A. Regulatory Framework 1. Federal Regulations a. Federal Water Pollution Control Act The Federal Water Pollution Control Act (Clean Water Act), also known as the CWA, was enacted in 1972 to restore and maintain the chemical, physical and biological integrity of the waters of the United States. The two-phase National Stormwater Program was established as part of the CWA. Phase 1 of the program requires discharges from Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems (MS4s) serving over 100,000 people to be covered under a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit. The City of Novato is considered a permittee under California’s statewide general permit (Water Quality Order No. 2003-0005-DWQ) for MS4s. Permitees must develop and implement a Stormwater Management Plan (SWMP) with the goal of reducing discharged pollutants to the maxi- mum extent. The City of Novato’s NPDES Storm Water Program prevents illicit discharges into drains, waterways and wetlands, and is discussed in more detail in Chapter 16, Utilities. b. National Flood Insurance Program Congress passed the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 and the Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973 to address the increasing cost of flood-related disaster relief. The intent of National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is to reduce the need for large, publicly-funded flood control structures and disaster relief by restricting development on floodplains. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) administers the NFIP to provide subsidized flood insurance to communities that comply with FEMA regulations and limit development on floodplains. -

NPDES Water Bodies

Attachment A: Detailed list of receiving water bodies within the Marin/Sonoma Mosquito Control District boundaries under the jurisdiction of Regional Water Quality Control Boards One and Two This list of watercourses in the San Francisco Bay Area groups rivers, creeks, sloughs, etc. according to the bodies of water they flow into. Tributaries are listed under the watercourses they feed, sorted by the elevation of the confluence so that tributaries entering nearest the sea appear they first. Numbers in parentheses are Geographic Nantes Information System feature ids. Watercourses which feed into the Pacific Ocean in Sonoma County north of Bodega Head, listed from north to south:W The Gualala River and its tributaries • Gualala River (253221): o North Fork (229679) - flows from Mendocino County. o South Fork (235010): Big Pepperwood Creek (219227) - flows from Mendocino County. • Rockpile Creek (231751) - flows from Mendocino County. Buckeye Creek (220029): Little Creek (227239) North Fork Buckeye Crcck (229647): Osser Creek (230143) • Roy Creek (231987) • Soda Springs Creek (234853) Wheatfield Fork (237594): Fuller Creek (223983): • Sullivan Crcck (235693) Boyd Creek (219738) • North Fork Fuller Creek (229676) South Fork Fuller Creek (235005) Haupt Creek (225023) • Tobacco Creek (236406) Elk Creek (223108) • )`louse Creek (225688): Soda Spring Creek (234845) Allen Creek (218142) Peppeawood Creek (230514): • Danfield Creek (222007): • Cow Creek (221691) • Jim Creek (226237) • Grasshopper Creek (224470) Britain Creek (219851) • Cedar Creek (220760) • Wolf Creek (238086) • Tombs Crock (236448) • Marshall Creek (228139): • McKenzie Creek (228391) Northern Sonoma Coast Watercourses which feed into the Pacific Ocean in Sonoma County between the Gualala and Russian Rivers, numbered from north to south: 1. -

Phase 3 Feasibility Report (Sections 1 & 2)

Section 1 Introduction This report, prepared in coordination with the North Bay Water Reuse Authority (Authority), presents an engineering evaluation and an economic and financial analysis of a proposed project for a regional approach to recycled water distribution in the North San Pablo Bay area of California. The report has been prepared by the Authority’s consultant, Camp Dresser & McKee Inc. in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the U. S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation Public Law 102-575, Title XVI (the Reclamation Wastewater and Groundwater Study and Facilities Act of 1992, as amended). Title XVI provides a mechanism for Federal participation and cost-sharing in approved recycled water projects and provides general authority for appraisal and feasibility studies. The Authority, established under a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in August 2005, is comprised of the Sonoma County Water Agency (SCWA), as Administrative Agency, together with four wastewater utilities as member agencies – the Las Gallinas Valley Sanitary District (LGVSD), the Novato Sanitary District (Novato SD), the Sonoma Valley County Sanitation District (SVCSD), and the Napa Sanitation District (Napa SD). North Marin Water District (NMWD) and Napa County are providing technical and financial support to the Authority. Under the MOU and its amendment, the Authority is exploring “the feasibility of coordinating interagency efforts to expand the beneficial use of recycled water in the North Bay Region thereby promoting the conservation of limited surface water and groundwater resources.” The proposed North San Pablo Bay Restoration and Reuse Project (Project), the subject and intended outcome of the Authority’s work, would alter the disposition of wastewater in the North Bay Region by reducing the volume of treated wastewater discharged into San Pablo Bay and its tributaries and instead providing increased recycled water supply to agricultural, urban, and environmental uses. -

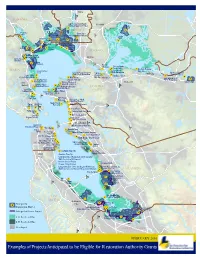

Examples of Projects Anticipated to Be Eligible for Restoration Authority Grants

Napa 221 |þ C a c h SONOMA e S lo u g Edgerly Island and South Fairfield h Wetlands Opportunity Area Rush Ranch NAPA Petaluma Lower Napa Marsh Skaggs Island Napa-Sonoma River Wetlands 80 Restoration ¨¦§ Suisun Lower Sonoma Marshes Marsh Creek Tolay Creek Strip Marsh Watershed Sears Point |þ37 Enhancements Bahia Tolay Creek Cullinan Wetlands Lagoon Ranch Lower Petaluma SOLANO er River iv R o Simmons Slough t r en e v m i Seasonal Wetlands Vallejo ra Novato Creek ac R S n i Baylands u q Bel Marin a o Keys Wetlands 780 J § Benicia n ¨¦ a Shoreline Pacheco Marsh S Restoration N Bay Point Regional e MARIN Lower Walnut w Y Lower Gallinas Shoreline ork Slou Creek Chelsea Wetlands & Lower Martinez Creek Restoration gh Big Break Regional Pinole Creek Restoration Pittsburg Shoreline-Oakley Lower Miller Regional McNabney Marsh Shoreline Creek/McInnis Marsh Point Pinole Martinez East Antioch Creek Creek to Bay Trash Regional Shoreline Marsh Restoration San Reduction Projects Breuner Marsh and Concord Dutch Slough Lower Rheem Creek Rafael Tiscornia Marsh 242 Restoration Project North Richmond Shoreline CONTRA |þ - San Pablo Marsh Lower Corte COSTA Madera Creek Point Molate, Lower Wildcat Richmond Creek Madera ¨¦§580 Bay Park Miller-Knoz, Richmond Western Stege Marsh Restoration Program Brooks Island Bothin Aramburu Point Isabel, Richmond Richmond 24 Marsh Island131 |þ |þ Albany Beach Richardson Berkeley North Strip Basin Bay Sausalito Berkeley Brickyard Eelgrass Preserve Point Emery Emeryville Crescent Oakland |þ13 Crissy Field Oakland Gateway Shoreline Educational Programs ¨¦§80 China Basin 680 Tennessee Alameda Point ¨¦§ Hollow Pier 70 - Crane Alameda Point Seaplane Lagoon Cove Park Lower Sausal Creek Pier 70 - Slipways Park Crown Beach – Neptune Point Islais Creek Warm Water Cove Park Pier 94- Wetlands Enhancement Martin Luther King Jr. -

Novato Creek Hydraulic Study Analysis of Alternatives

NOVATO CREEK HYDRAULIC STUDY ANALYSIS OF ALTERNATIVES PREPARED FOR: County of Marin Department of Public Works BY: Kamman Hydrology & Engineering, Inc. 7 MT. LASSEN DRIVE, SUITE B250 San Rafael, CA 94903 (415) 491-9600 IN ASSOCIATION WITH: WRECO 1243 Alpine Rd, Suite 108 Walnut Creek, CA 94596 June 2016 Novato Creek Hydraulic Study: Alternatives Development and Hydraulic Analysis Final Report: June, 2016 Services provided pursuant to this Agreement are intended for planning purposes for the The Marin County Department of Public Works i‐1 Novato Creek Hydraulic Study: Alternatives Development and Hydraulic Analysis Final Report: June, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... ES‐1 1.1 Summary of Study Alternatives: .............................................................................................. ES‐3 Short Term Alternative: .................................................................................................... ES‐4 Medium Term Alternative: ............................................................................................. ES‐10 Long Term Alternative: ................................................................................................... ES‐14 1.2 Alternatives Analysis .............................................................................................................. ES‐18 1.3 General Flood Study Findings ............................................................................................... -

Novato Creek Watershed: Existing Conditions Model Report

Novato Creek Watershed: Existing Conditions Model Report LIST OF APPENDICES (May 2014) Page Appendix A: Bayland Model Analysis A.1: EC Bayland Model Simulation Results: Q10,Q50 and Q100…………………………………….3 A.2: Bayland Model Sensitivity Analysis……………………………………………………………………....47 Appendix B: Bayland Basin Characteristics……………………………………………………………………………….65 Appendix C: Novato Creek Survey and Terrain Data Synthesis C.1: Kruse Imaging Bare Earth DEM Metadata Summary (Kruse, 2012)………………………71 C.2 KHE Survey Data Synthesis……………………………………………………………………………………85 C.3: Novato Creek Control Point Network and Channel Surveys (CPI, 2012)…………….142 Appendix D: Hydrology and Watershed Modeling Data Sets D.1: Draft Novato Hydrology (HEC HMS) Memorandum (MCFC, 2013)……………………..152 D.2: HMS Model Review Technical Memorandum (WRECO, 2013)……………………………174 D.4 : MCFC Pump Operations Guidelines (MCFC, 2010)……………………………………………187 D.5 BMKCSD Lagoon Operations Guidelines (CLE, 2012)…………………………………………..191 Appendix E: Nave Gardens: SWMM Urban Drainage Model (WRECO, 2014)…………………………194 Appendix F: Pacheco Pond HECRAS Analysis (KHE, 2014)………………………………………………………223 Appendix G: Sediment Loading and Transport Characteristics ……………………………………………..243 Draft Hydraulic Assessment of Existing Conditions: Novato Creek Watershed Project DRAFT 2014_06_02 Appendix A: EC Bayland Model Analysis: A.1: EC Bayland Model Simulation Results: Q10, Q50 and Q100 A.2: Bayland Model Sensitivity Analysis Draft Hydraulic Assessment of Existing Conditions: Novato Creek Watershed Project DRAFT 2014_06_02 A.1: EC Bayland Model Simulation Results: Q10, Q50 and Q100 Novato Bayland EC_Q10 16 15 Legend CABMK Breach 14 BMKCSD No. Lock DS Hwy37 13 Mid DIB NWPRR 12 Nave Gardens 11 10 9 8 7 WS Elevation (ft)WS Elevation (ft) 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 0.00 0.50 1.00 1.50 2.00 2.50 3.00 3.50 4.00 Time (days) KHE Inc www.KHE-Inc.com Novato Bayland EC:Q10_SLR16 16 15 Legend 14 CABMK Breach BMKCSD No. -

Year 1 Monitoring Report Diazinon and Pesticide-Related Toxicity

OCTOBER 2016 MARIN COUNTY STORMWATER POLLUTION PREVENTION PROGRAM AND CITY OF PETALUMA Year 1 Monitoring Report Diazinon and Pesticide-Related Toxicity TMDL Monitoring Program in Urban Creeks submitted to SAN FRANCISCO BAY REGIONAL WATER QUALITY CONTROL BOARD prepared by LARRY WALKER ASSOCIATES ~ This Page Intentionally Left Blank ~ Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 2. Monitoring Methods, Stations, and Parameters ................................................................ 2 2.1. Monitoring Stations ........................................................................................................ 2 2.2. Monitoring Events .......................................................................................................... 2 2.3. Monitoring Constituents ................................................................................................. 4 2.4. Stream Flow Analysis ..................................................................................................... 4 2.5. Analytical Methods ......................................................................................................... 5 3. Event Summaries .................................................................................................................. 7 3.1. Event 1: January 5, 2016 ................................................................................................. 7 3.2. Event 2: March 5, 2016 .................................................................................................. -

Salmon, Steelhead, and Trout in California

! "#$%&'(!")**$+*#,(!#',!-.&/)! 0'!1#$02&.'0#! !"#"$%&'(&#)&*+,-.+#"/0&1#$)#& !"#$%&#'"(&))*++*&,$-"./"012*3&#,*1"4#&5'6"7889" PETER B. MOYLE, JOSHUA A. ISRAEL, AND SABRA E. PURDY CENTER FOR WATERSHED SCIENCES, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, DAVIS DAVIS, CA 95616 -#3$*!&2!1&')*')4! !0:;<=>?@AB?;4C"DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"E" F;4G<@H04F<;"DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"I" :>!B!4J"B<H;4!F;C"KG<LF;0?"=F;4?G"C4??>J?!@""DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"7E" :>!B!4J"B<H;4!F;C"KG<LF;0?"CHBB?G"C4??>J?!@"DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"E7" ;<G4J?G;"0!>FM<G;F!"0<!C4!>"=F;4?G"C4??>J?!@""DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"IE" ;<G4J?G;"0!>FM<G;F!"0<!C4!>"CHBB?G"C4??>J?!@""DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"NO" 0?;4G!>"L!>>?P"C4??>J?!@"DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"OI" 0?;4G!>"0!>FM<G;F!"0<!C4"C4??>J?!@""DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"Q7" C<H4JR0?;4G!>"0!>FM<G;F!"0<!C4"C4??>J?!@""DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"QS" C<H4J?G;"0!>FM<G;F!"0<!C4"C4??>J?!@""DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"9O" G?CF@?;4"0<!C4!>"G!F;T<="4G<H4"DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD"SQ"