How (Not) to Write a Play About a Pandemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

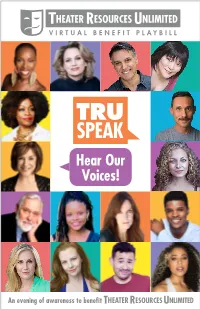

TRU Speak Program 021821 XS

THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED VIRTUAL BENEFIT PLAYBILL TRU SPEAK Hear Our Voices! An evening of awareness to benefit THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED executive producer Bob Ost associate producers Iben Cenholt and Joe Nelms benefit chair Sanford Silverberg plays produced by Jonathan Hogue, Stephanie Pope Lofgren, James Rocco, Claudia Zahn assistant to the producers Maureen Condon technical coordinator Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms editor-technologists Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms, Andrea Lynn Green, Carley Santori, Henry Garrou/Whitetree, LLC video editors Sam Berland/Play It Again Sam’s Video Productions, Joe Nelms art direction & graphics Gary Hughes casting by Jamibeth Margolis Casting Social Media Coordinator Jeslie Pineda featuring MAGGIE BAIRD • BRENDAN BRADLEY • BRENDA BRAXTON JIM BROCHU • NICK CEARLEY • ROBERT CUCCIOLI • ANDREA LYNN GREEN ANN HARADA • DICKIE HEARTS • CADY HUFFMAN • CRYSTAL KELLOGG WILL MADER • LAUREN MOLINA • JANA ROBBINS • REGINA TAYLOR CRYSTAL TIGNEY • TATIANA WECHSLER with Robert Batiste, Jianzi Colon-Soto, Gha'il Rhodes Benjamin, Adante Carter, Tyrone Hall, Shariff Sinclair, Taiya, and Stephanie Pope Lofgren as the Voice of TRU special appearances by JERRY MITCHELL • BAAYORK LEE • JAMES MORGAN • JILL PAICE TONYA PINKINS •DOMINIQUE SHARPTON • RON SIMONS HALEY SWINDAL • CHERYL WIESENFELD TRUSpeak VIP After Party hosted by Write Act Repertory TRUSpeak VIP After Party production and tech John Lant, Tamra Pica, Iben Cenholt, Jennifer Stewart, Emily Pierce Virtual Happy Hour an online musical by Richard Castle & Matthew Levine directed -

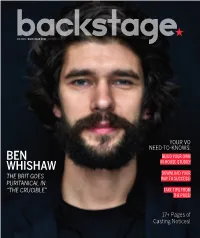

Ben Whishaw Photographed by Matt Doyle at the Walter Kerr Theatre in NYC on Feb

03.17.16 • BACKSTAGE.COM YOUR VO NEED-TO-KNOWS: BEN BUILD YOUR OWN WHISHAW IN-HOUSE STUDIO! DOWNLOAD YOUR THE BRIT GOES WAY TO SUCCESS! PURITANICAL IN “THE CRUCIBLE” TAKE TIPS FROM THE PROS! 17+ Pages of Casting Notices! NEW YORK STELLAADLER.COM 212-689-0087 31 W 27TH ST, FL 3 NEW YORK, NY 10001 [email protected] THE PLACE WHERE RIGOROUS ACTOR TRAINING AND SOCIAL JUSTICE MEET. SUMMER APPLICATION DEADLINE EXTENDED: APRIL 1, 2016 TEEN SUMMER CONSERVATORY 5 Weeks, July 11th - August 12th, 2016 Professional actor training intensive for the serious young actor ages 14-17 taught by our world-class faculty! SUMMER CONSERVATORY 10 Weeks, June 6 - August 12, 2016 The Nation’s Most Popular Summer Training Program for the Dedicated Actor. SUMMER INTENSIVES 5-Week Advanced Level Training Courses Shakespeare Intensive Chekhov Intensive Physical Theatre Intensive Musical Theatre Intensive Actor Warrior Intensive Film & Television Acting Intensive The Stella Adler Studio of Acting/Art of Acting Studio is a 501(c)3 not-for-prot organization and is accredited with the National Association of Schools of Theatre LOS ANGELES ARTOFACTINGSTUDIO.COM 323-601-5310 1017 N ORANGE DR LOS ANGELES, CA 90038 [email protected] by: AK47 Division CONTENTS vol.57,no.11|03.17.16 NEWS 6 Ourrecapofthe37thannualYoung Artist Awardswinners 7 Thisweek’sroundupofwho’scasting whatstarringwhom 8 7 brilliantactorstowatchonNetflix ADVICE 11 NOTEFROMTHECD Themonsterwithin 11 #IGOTCAST EbonyObsidian 12 SECRET AGENTMAN Redlight/greenlight 13 #IGOTCAST KahliaDavis -

Suspect Netted in Thefts from Salvage Santa

5 NONPROFITS RECEIVE RECOVERY GRANTS LOCAL | B1 PANAMA CITY LOCAL & STATE | B1 PARKER LEADERS MULL MOBILE HOME LIMITS Thursday, August 22, 2019 www.newsherald.com @The_News_Herald facebook.com/panamacitynewsherald 75¢ Trump moves to end limits on migrant detention By Colleen Long A court fight is almost cer- days in detention. families in detention much following reports of dire con- and Amy Taxin tain to follow, challenging Homeland Security offi- longer than 20 days. ditions in detention facilities, The Associated Press the attempt to hold migrant cials say they are adopting Tightening immigration is and it is questionable whether families until asylum cases their own regulations that a signature issue for Presi- courts will let the administra- WASHINGTON — The are decided. reflect the “Flores agree- dent Donald Trump, aimed at tion move forward with the Trump administration is A current settlement over- ment,” which has been in restricting the movement of policy. moving to end an agreement seen by the federal courts effect since 1997. They say asylum seekers in the country Trump defended it, saying, limiting how long migrant now requires the govern- there is no longer a need for and deterring more migrants “I’m the one that kept the children can be kept in deten- ment to keep children in the the court involvement, which from crossing the border. families together.” tion, the president’s latest least restrictive setting and was only meant to be tempo- The move by the admin- The Mexican government effort to curb immigration at to release them as quickly as rary. But the new rules would istration immediately the Mexican border. -

2015 Next Wave Festival DEC 2015

2015 Next Wave Festival DEC 2015 Shinique Smith, Abiding Light, 2015 Published by: Season Sponsor: #BAMNextWave #SteelHammer Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Steel Hammer BAM Harvey Theater Dec 2—5 at 7:30pm; Dec 6 at 3pm Running time: one hour & 55 minutes, no intermission Julia Wolfe and SITI Company Bang on a Can All-Stars Directed by Anne Bogart Music & lyrics by Julia Wolfe Original text by Kia Corthron, Will Power, Carl Hancock Rux, and Regina Taylor Music performed by Bang on a Can All-Stars Play performed & created by SITI Company Scenic & costume design by James Schuette Lighting by Brian H Scott Sound design by Andrew Cotton and Christian Frederickson Choreography by Barney O’Hanlon Season Sponsor: Steel Hammer premiered at Actors Theatre of Louisville in the 2014 Humana Festival of New American Plays In memory of Robert W. Wilson, with gratitude for his visionary and generous support of BAM STEEL HAMMER Akiko Aizawa Ashley Bathgate Eric Berryman Robert Black Patrice Johnson Vicky Chow David Cossin Emily Eagen Chevannes Katie Geissinger Gian-Murray Gianino Barney O’Hanlon Molly Quinn Mark Stewart Ken Thomson Stephen Duff Webber Steel Hammer CAST Akiko Aizawa* Eric Berryman* Patrice Johnson Chevannes* Gian-Murray Gianino* Barney O’Hanlon* Stephen Duff Webber* BANG ON A CAN ALL-STARS Ashley Bathgate cello Robert Black bass Vicky Chow piano David Cossin -

The Journal of the Dramatists Guild of America, Inc

The Journal of the Dramatists Guild of America, Inc. The the ageissue 2016 NOV/DEC $7 USD €10 EUR www.dramatistsguild.com FrontCOVER.indd 1 10/5/16 12:57 PM To enroll, go to http://www.dginstitute.org SEP/OCTJul/Aug DGI 16 ad.indd FrontCOVERs.indd 1 2 5/23/168/8/16 1:341:52 PM VOL. 19 No 2 TABLE OF NOV/DEC 2016 2 Editor’s Notes CONTENTS 3 Dear Dramatist 4 News 7 Inspiration – KIRSTEN CHILDS 8 The Craft – KAREN HARTMAN 10 Edward Albee 1928-2016 13 “Emerging” After 50 with NANCY GALL-CLAYTON, JOSH GERSHICK, BRUCE OLAV SOLHEIM, and TSEHAYE GERALYN HEBERT, moderated by AMY CRIDER. Sidebars by ANTHONY E. GALLO, PATRICIA WILMOT CHRISTGAU, and SHELDON FRIEDMAN 20 Kander and Pierce by MARC ACITO 28 Profile: Gary Garrison with CHISA HUTCHINSON, CHRISTINE TOY JOHNSON, and LARRY DEAN HARRIS 34 Writing for Young(er) Audiences with MICHAEL BOBBITT, LYDIA DIAMOND, ZINA GOLDRICH, and SARAH HAMMOND, moderated by ADAM GWON 40 A Primer on Literary Executors – Part One by ELLEN F. BROWN 44 James Houghton: A Tribute with JOHN GUARE, ADRIENNE KENNEDY, WILL ENO, NAOMI WALLACE, DAVID HENRY HWANG, The REGINA TAYLOR, and TONY KUSHNER Dramatistis the official journal of Dramatists Guild of America, the professional organization of 48 DG Fellows: RACHEL GRIFFIN, SYLVIA KHOURY playwrights, composers, lyricists and librettists. 54 National Reports It is the only 67 From the Desk of Dramatists Guild Fund by CHISA HUTCHINSON national magazine 68 From the Desk of Business Affairs by AMY VONVETT devoted to the business and craft 70 Dramatists Diary of writing for 75 New Members theatre. -

WELCOME to V-DAY's 2003 PRESS KIT Thank You for Taking the First Step in Helping to Stop Violence Against Women and Girls

WELCOME TO V-DAY’S 2003 PRESS KIT Thank you for taking the first step in helping to stop violence against women and girls. V-Day relies on the media to help get the word out about the global reach and long-lasting effects of violence. With your assistance, we hope your audience is compelled to take action to stop the violence, rape, domestic battery, incest, female genital mutilation, sexual slavery—that many women and girls face every day around the world. Our goal is to provide media with everything you need to present the most interesting and meaningful story possible. If you require additional information or interviews, please contact Susan Celia Swan at [email protected] . In addition, you can find all of our press releases (including the most recent) posted at our site in the Press Release section. Thank you again for joining V-Day in our fight to end violence against women and girls. Susan Celia Swan Jerri Lynn Fields Media & Communications Executive Director 212-445-3288 914-835-6740 CONTENTS OF THIS KIT Page 1: Welcome To V-Day’s 2003 Press Kit Page 2: 2003 Vision Statement Page 3: 2003 Launch Press Release Page 7: About V-Day and Mission Statement Page 8: Star Support: The Vulva Choir Page 11: Quote Sheet Page 12: Biography of V-Day Founder and Artistic Director/Playwright Eve Ensler Page 13: Take Action to Stop Violence Page 14: V-Day College and Worldwide Campaigns Page 15: Selected Media Coverage Page 38: Selected Press Releases V-DAY 2003: FROM V-DAY TO V-WORLD Last year V-Day happened in 800 venues around the world. -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H. -

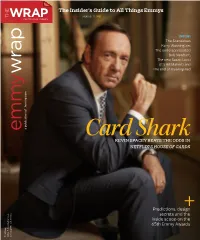

The Insider's Guide to All Things Emmys

The Insider’s Guide to All Things Emmys DOWN TO THE WIRE | AUGUST 12, 2013 COVERING HOLLYWOOD INSIDE: The Scandalous Kerry Washington, The underappreciated Bob Newhart, The new Susan Lucci (it's Bill Maher!) and The end of Breaking Bad a publication of thewrap.com of a publication Card Shark KEVIN SPACEY BEATS THE ODDS IN NETFLIX'S HOUSE OF CARDS Predictions, design+ secrets and the inside scoop on the 65th Emmy Awards TheWrap 2855 S. Barrington Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90064 CONGRATULATIONS TO ALL OUR 110 NOMINATIONS! 2013 PRIMETIME EMMY ® N O M I N E E S ! BEHIND THE CANDELABRA PHIL SPECTOR GAME OF THRONES® BOARDWALK EMPIRE® GIRLSSM REAL TIME WITH MEA MAXIMA CULPA: CROSSFIRE HURRICANE Jerry Weintraub Productions in association with Levinson/Fontana Productions in association with Bighead, Littlehead, Television 360, Startling Leverage, Closest to the Hole Productions, Apatow Productions and I am Jenni Konner BILL MAHER SILENCE IN THE Tremolo Productions, Milkwood Films, Eagle ® ® HBO Films HBO Films Television and Generator Productions in association Sikelia Productions and Cold Front Productions Productions in association with HBO Entertainment Bill Maher Productions and Brad Grey Television HOUSE OF GOD Rock Entertainment and the Rolling Stones in ® with HBO Entertainment in association with HBO Entertainment ® association with HBO Documentary Films OUTSTANDING MINISERIES OR MOVIE OUTSTANDING MINISERIES OR MOVIE OUTSTANDING COMEDY SERIES in association with HBO Entertainment HBO Documentary Films in association with Jerry Weintraub, Executive Producer; Barry Levinson, David Mamet, Executive Producers; OUTSTANDING DRAMA SERIES SUPPORTING ACTOR IN A DRAMA SERIES Judd Apatow, Jenni Konner, Lena Dunham, OUTSTANDING VARIETY SERIES Jigsaw Productions, Wider Film Projects and OUTSTANDING DOCUMENTARY OR NONFICTION Gregory Jacobs, Susan Ekins, Michael Polaire, Michael Hausman, Produced by David Benio , D.B. -

Debs Award Recipient

P.O.P.O. BOXBO X89454,43 ,TTERREERRE HAUTE,HAUTE, INDIANAINDIANA 47808-945447808 FALL 2012 DEBS AWARD RECIPIENT KEYNOTE/ newly merged Amalgamated Clothing and PRESENTATION Textile Workers Union; was appointed SPEAKER Civil Rights Director and elected as Manager for the laundry division affiliate where she served for more than 13 years. She was elected International Vice President in 1991, and has been re-elected every election since that time. In 1995, she was elected as part of John Sweeney’s team to the AFL-CIO Executive Council as a Vice President, and served for 10 years. Sister Brown’s tremendous commitment to her community and her fellow man is apparent through the many boards and Clayola Brown organizations she currently serves on, Regina Taylor including serving as a National Board Our choice of Clayola Brown for the 2012 With an impressive body of work that of Director for the Amalgamated Bank. Debs Award is timely, to say the least. The encompasses film, television, theater issues most clearly dividing Republicans She serves on the National Board of the and writing, Regina Taylor’s career and Democrats relate to minorities and NAACP (including chairing both the continues to evolve with exciting and women: their personal freedom and NAACP Image Awards Committee and challenging projects. Taylor is best economic well-being. Ms. Brown has the Labor Ad-Hoc Committee). known to television audiences for served all her adult life in advancing those She is a 10 year member of the Board her role as Lilly Harper in the series rights. of the Congressional Black Caucus “I’ll Fly Away.” She received many accolades for her performance in the Currently Clayola Brown serves in dual Foundation and the United Nations Advisory Council. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

Ano mmìsìiy cwt« woimt w ARCHMS/SPECiÂl CßLLECIlöKS 111 lAMES P. BMMEÏ DR., S. H. AILANIA.^. 30314 öl veri ne MAY/JUNE 1996 MORRIS BROWN COLLEGE “Dedicated to Educating the Leaders of Tomorrow” AIDS Are You Next? by Monique Jennings uring the early eighties, a deadly virus was discovered. Many people who carry D the virus don’t know how they contract ed it. The nation’s concerns about this horrify ing disease caused researchers to take action. Today, researchers say there is no cure for HIV/AIDS virus. One researcher said, “Getting AIDS is like playing Russian roulette with your life, so you might as well put a gun to your head and kill yourself.” The solution to the problem is abstinence. Another experimentalist says, “It is common among heterosexuals, homosexuals, and bisexuals.” The main group contracting the virus are college students. How does this effect college the HIV/AIDS virus, you are putting students? One student said, “There others at risk by having unprotected were many times I’ve had unprotected sex. A person can’t tell if another person sex.” Some students say if they had the has the HIV virus unless they are in AIDS virus, they would spread it around the final stages. to other people. Within the Atlanta According to the Department of Look at me, can you tell if I have AIDS? University Center there is a percentage Health and Human Services, more than of students carrying the HIV/AIDS 60,918 cases of AIDS have been This is one of the most deadly they need to wake up. -

Reminder List of Eligible Releases for Distinguished Achievements During 1996 A

Reminder List of Eligible Releases for Distinguished Achievements during 1996 A ACROSS THE SEA OF TIME Peter Reznik. Abby Lewis. Dennis O'Connor. THE ADVENTURES OF PINOCCHIO Martin Landau. Jonathan Taylor Thomas. Genevieve Bujold. Udo Kier. Bebe Neuwirth. Rob Schneider. Corey Carrier. Marcello Magni. Dawn French. Richard Claxton. Griff Rhys Jones. John Sessions. Jean-Claude Drouot. Jean-Claude Dreyfus. Teco Celio. Wilfred Benaiche. Erik Averlont. Vladimir Koval. Daniela Tolkein. Anita Zagaria. Lilian Malkina. Vaclav Vydra. Petr Bednar. Stefan Weclawek. Zdenek Podhursky. Jiri Kvasnicka. Gorden Lovitt. Jan Slovak. Dean Cook. Joe Swash. Oliver Barron. Jake Court. Luke Deleon. Kevin Dorsey. Thomas Orange. Sean Woodward. Jiri Patocka. Lida Vlaskova. Paavel Koci. Voiceovers: Jonathan Taylor Thomas. David Doyle. ALASKA Thora Birch. Vincent Kartheiser. Dirk Benedict. Charlton Heston. Duncan Fraser. Gordon Tootoosis. Ben Cardinal. ALL DOGS GO TO HEAVEN 2 Animation voiceovers: Ernest Borgnine. Bebe Neuwirth. Charlie Sheen. Hamilton Camp. Steve Mackall. Dan Castellaneta. Dom DeLuise. Tony Jay. Jim Cummings. Wallace Shawn. Sheena Easton. George Hearn. Adam Wylie. Kevin Michael Richardson. Pat Corley. Marabina Jaimes. Bobby DiCicco. Annette Helde. Maurice La Marche. ALL'S FAIR IN LOVE & WAR Sartaj Khan. Miki O'Brien. Bill Trillo. Christopher B. Aponte. Tony Pressman. Angela Mia. William Night. Jerry Mullen. Robert Mont. Andy Innes. Jenny Z. Barbara Nelson. Rick Nardi. Steven Sahar. Giuliano Belle. Robert Donovan. Art Samuels. J. Paul Vincent. Doug Crews. Gene Ober. Blu Bluestein. "TR" Richards. Dug Credit. Tom Gumpper. Marge Ann Windish. Adam Gordan. Nicola Kelly. Craig Walker. Gary Sohl. Sam Sarpong. Michelle Chastain. Annette Harper. Jason Graziano. Gil Ferrales. Kevin Scott. Carl Thibault.