Breathing Memory2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MTO 11.4: Spicer, Review of the Beatles As Musicians

Volume 11, Number 4, October 2005 Copyright © 2005 Society for Music Theory Mark Spicer Received October 2005 [1] As I thought about how best to begin this review, an article by David Fricke in the latest issue of Rolling Stone caught my attention.(1) Entitled “Beatles Maniacs,” the article tells the tale of the Fab Faux, a New York-based Beatles tribute group— founded in 1998 by Will Lee (longtime bassist for Paul Schaffer’s CBS Orchestra on the Late Show With David Letterman)—that has quickly risen to become “the most-accomplished band in the Beatles-cover business.” By painstakingly learning their respective parts note-by-note from the original studio recordings, the Fab Faux to date have mastered and performed live “160 of the 211 songs in the official canon.”(2) Lee likens his group’s approach to performing the Beatles to “the way classical musicians start a chamber orchestra to play Mozart . as perfectly as we can.” As the Faux’s drummer Rich Pagano puts it, “[t]his is the greatest music ever written, and we’re such freaks for it.” [2] It’s been over thirty-five years since the real Fab Four called it quits, and the group is now down to two surviving members, yet somehow the Beatles remain as popular as ever. Hardly a month goes by, it seems, without something new and Beatle-related appearing in the mass media to remind us of just how important this group has been, and continues to be, in shaping our postmodern world. For example, as I write this, the current issue of TV Guide (August 14–20, 2005) is a “special tribute” issue commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the Beatles’ sold-out performance at New York’s Shea Stadium on August 15, 1965—a concert which, as the magazine notes, marked the “dawning of a new era for rock music” where “[v]ast outdoor shows would become the superstar standard.”(3) The cover of my copy—one of four covers for this week’s issue, each featuring a different Beatle—boasts a photograph of Paul McCartney onstage at the Shea concert, his famous Höfner “violin” bass gripped in one hand as he waves to the crowd with the other. -

TOTO Bio (PDF)

TOTO Bio Few ensembles in the history of recorded music have individually or collectively had a larger imprint on pop culture than the members of TOTO. As individuals, the band members’ imprint can be heard on an astonishing 5000 albums that together amass a sales history of a HALF A BILLION albums. Amongst these recordings, NARAS applauded the performances with 225 Grammy nominations. Band members were South Park characters, while Family Guy did an entire episode on the band's hit "Africa." As a band, TOTO sold 35 million albums, and today continue to be a worldwide arena draw staging standing room only events across the globe. They are pop culture, and are one of the few 70s bands that have endured the changing trends and styles, and 35 years in to a career enjoy a multi-generational fan base. It is not an exaggeration to estimate that 95% of the world's population has heard a performance by a member of TOTO. The list of those they individually collaborated with reads like a who's who of Rock & Roll Hall of Famers, alongside the biggest names in music. The band took a page from their heroes The Beatles playbook and created a collective that features multiple singers, songwriters, producers, and multi-instrumentalists. Guitarist Steve Lukather aka Luke has performed on 2000 albums, with artists across the musical spectrum that include Michael Jackson, Roger Waters, Miles Davis, Joe Satriani, Steve Vai, Rod Stewart, Jeff Beck, Don Henley, Alice Cooper, Cheap Trick and many more. His solo career encompasses a catalog of ten albums and multiple DVDs that collectively encompass sales exceeding 500,000 copies. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Paul Mccartney – New • Mary J Blige – a Mary

Paul McCartney – New Mary J Blige – A Mary Christmas Luciano Pavarotti – The 50 Greatest Tracks New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI13-42 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: KATY PERRY / PRISM Bar Code: Cat. #: B001921602 Price Code: SPS Order Due: Release Date: October 22, 2013 File: POP Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: 6 02537 53232 2 Key Tracks: ROAR ROAR Artist/Title: KATY PERRY / PRISM (DELUXE) Bar Code: Cat. #: B001921502 Price Code: AV Order Due: October 22, 2013 Release Date: October 22, 2013 6 02537 53233 9 File: POP Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: Key Tracks: ROAR Artist/Title: KATY PERRY / PRISM (VINYL) Bar Code: Cat. #: B001921401 Price Code: FB Order Due: October 22, 2013 Release Date: October 22, 2013 6 02537 53234 6 File: POP Genre Code: 33 Box Lot: Key Tracks: Vinyl is one way sale ROAR Project Overview: With global sales of over 10 million albums and 71 million digital singles, Katy Perry returns with her third studio album for Capitol Records: PRISM. Katy’s previous release garnered 8 #1 singles from one album (TEENAGE DREAM). She also holds the title for the longest stay in the Top Ten of Billboard’s Hot 100 – 66 weeks – shattering a 20‐year record. Katy Perry is the most‐followed female artist on Twitter, and has the second‐largest Twitter account in the world, with over 41 million followers. -

Paul Mccartney's

THE ULTIMATE HYBRID DRUMKIT FROM $ WIN YAMAHA VALUED OVER 5,700 • IMAGINE DRAGONS • JOEY JORDISON MODERNTHE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE DRUMMERJANUARY 2014 AFROBEAT 20DOUBLE BASS SECRETS PARADIDDLE PATTERNS MILES ARNTZEN ON TONY ALLEN CUSTOMIZE YOUR KIT WITH FOUND METAL ED SHAUGHNESSY 1929–2013 Paul McCartney’s Abe Laboriel Jr. BOOMY-LICIOUS MODERNDRUMMER.com + BENNY GREB ON DISCIPLINE + SETH RAUSCH OF LITTLE BIG TOWN + PEDRITO MARTINEZ PERCUSSION SENSATION + SIMMONS SD1000 E-KIT AND CRUSH ACRYLIC DRUMSET ON REVIEW paiste.com LEGENDARY SOUND FOR ROCK & BEYOND PAUL McCARTNEY PAUL ABE LABORIEL JR. ABE LABORIEL JR. «2002 cymbals are pure Rock n' Roll! They are punchy and shimmer like no other cymbals. The versatility is unmatched. Whether I'm recording or reaching the back of a stadium the sound is brilliant perfection! Long live 2002's!» 2002 SERIES The legendary cymbals that defined the sound of generations of drummers since the early days of Rock. The present 2002 is built on the foundation of the original classic cymbals and is expanded by modern sounds for today‘s popular music. 2002 cymbals are handcrafted from start to finish by highly skilled Swiss craftsmen. QUALITY HAND CRAFTED CYMBALS MADE IN SWITZERLAND Member of the Pearl Export Owners Group Since 1982 Ray Luzier was nine when he first told his friends he owned Pearl Export, and he hasn’t slowed down since. Now the series that kick-started a thousand careers and revolutionized drums is back and ready to do it again. Pearl Export Series brings true high-end performance to the masses. Join the Pearl Export Owners Group. -

Master Song List Keyboardist for Hire

Ryan McNevin – Master Song List Keyboardist For Hire Updated: September 6, 2021 # 38 Special – Hold On Loosely 54/40 – I Go Blind A ACDC – Highway To Hell Alice Cooper – I Am Made Of You ACDC – If You Want Blood (You've Got It) Alice Cooper – I'm Eighteen ACDC – Thunderstruck Alice Cooper – No More Mr. Nice Guy ACDC – TNT Alice Cooper – Under My Wheels ACDC – You Shook Me All Night Long Alice Merton – No Roots Adele – Set Fire To The Rain Allman Brothers – Ramblin' Man Adele – Someone Like You Allman Brothers – Statesboro Blues Aerosmith – Amazing Allman Brothers – Whipping Post Aerosmith – Angel Amanda Marshall – Beautiful Goodbye Aerosmith – Come Together Amy Winehouse – Valerie Aerosmith – Dude (Looks Like A Lady) Anastacia – Sick And Tired Aerosmith – Just Feel Better April Wine – Enough Is Enough Aerosmith – Last Child April Wine – I Wouldn't Want To Lose Your Love Aerosmith – Sweet Emotion April Wine – Rock N' Roll Is A Vicious Game Airbourne – Live It Up April Wine – Roller Al Green – Let's Stay Together Autograph – Turn Up The Radio Alanis Morissette – Reasons I Drink Avicii – Wake Me Up Alannah Myles – Black Velvet Avril Lavigne – Birdie Alannah Myles – Still Got This Thing For You Avril Lavigne – Head Above Water Alan Jackson – Don't Rock The Jukebox Avril Lavigne – Let You Go Alan Parsons – Oh Life (There Must Be More) Avril Lavigne – Warrior Alan Parsons – Old And Wise Alan Parsons – Time Aldo Nova – Fantasy B B52s – Love Shack Ben E. King – Stand By Me BT Overdrive – Taking Care Of Business Ben Folds – Gone Bad Company – -

Groundup Music Festival Reveals 2020 Lineup With

GROUNDUP MUSIC FESTIVAL REVEALS 2020 LINEUP WITH SNARKY PUPPY, BRIAN BLADE & THE FELLOWSHIP BAND, LETTUCE, CÉCILE MCLORIN SALVANT, LILA DOWNS, MICHAEL MCDONALD ACOUSTIC QUARTET, CHRIS POTTER, CHRISTIAN SCOTT AND MORE! February 14-16, 2020 at the North Beach Bandshell in Miami, FL Tickets on Sale Now! The fourth annual GroundUP Music Festival returns to the oceanside North Beach Bandshell in Miami Beach, Florida, February 14-16, 2020. Hosted by three-time Grammy award-winning collective Snarky Puppy, GroundUP will feature a special set from the band each day along with performances from an eclectic list of international artists. Joining Snarky Puppy is iconic singer-songwriter/keyboardist Michael McDonald from The Doobie Brothers and Steely Dan performing with Chris Potter, Michael League and Jamison Ross for a special acoustic set, progressive future funk collective Lettuce, saxophone virtuoso Chris Potter as artist-at-large, Grammy Award-winning Mexican folk-fusion singer Lila Downs, powerful jazz trumpeter Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah, jazz drummer and songwriter Brian Blade & The Fellowship Band, jazz vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant, and more. The Valentine’s Day weekend event also features global artists from Colombia, Portugal, Brazil, Chile, Switzerland, and Greece, making it a true exploration of world music. “My vision for the festival is for people to maybe not recognize many artists on the bill but end up with a list of new artists they've discovered,” said Snarky Puppy’s bandleader Michael League. “That's the dream for me -- to have people come and experience everything blind, in a very pure and open-minded way.” Hailed by the Miami New Times as “one of the 10 best music events” in Miami, GroundUP will take place once again at the North Beach Bandshell and sprawling adjacent Palm Grove Park and beachfront complex. -

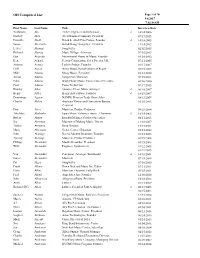

OH Completed List

OH Completed List Page 1 of 70 9/6/2017 7:02:48AM First Name Last Name Title Interview Date Yoshiharu Abe TEAC, Engineer and Innovator d 10/14/2006 Norbert Abel Abel Hammer Company, President 07/17/2015 David L. Abell David L. Abell Fine Pianos, Founder d 10/18/2005 Susan Aberbach Hill & Range Songs Inc., President 11/14/2012 Lester Abrams Songwriter 02/02/2015 Richard Abreau Music Village, Advocate 07/03/2013 Gus Acevedo International House of Music, Founder 01/20/2012 Ken Achard Peavey Corporation, Sales Director UK 07/11/2005 Antonio Acosta Luthier Strings, Founder 01/17/2007 Cliff Acred Amro Music, Band Instrument Repair 07/15/2013 Mike Adams Moog Music, President 01/13/2010 Arthur Adams Songwriter, Musician 09/25/2011 Edna Adams World Wide Music, Former Sales Executive 04/16/2010 Paul Adams Piano Technician 07/17/2015 Hawley Ades Shawnee Press, Music Arranger d 06/10/2007 Henry Adler Henry Adler Music, Founder d 10/19/2007 Dominique Agnew NAMM, Director Trade Show Sales 08/13/2009 Charles Ahlers Anaheim Visitor and Convention Bureau, 01/25/2013 President Don Airey Musician, Product Endorser 09/29/2014 Takehiko Akaboshi Japan Music Volunteer Assoc., Chairman d 10/14/2006 Bulent Akbay Istanbul Mehmet, Product Specialist 04/11/2013 Joy Akerman Museum of Making Music, Docent 11/30/2007 Toshio Akiyama Band Director 12/15/2011 Marty Albertson Guitar Center, Chairman 01/21/2012 John Aldridge Not So Modern Drummer, Founder 01/23/2005 Tommy Aldridge Musician, Product Endorser 01/19/2008 Philipp Alexander Musik Alexander, President 03/15/2008 Will Alexander Engineer, Synthesizers 01/22/2005 01/22/2015 Van Alexander Composer, Arranger, Bandleader d 10/18/2001 James Alexander Musician 07/15/2015 Pat Alger Songwriter 07/10/2015 Frank Alkyer Down Beat and Music Inc, Editor 03/31/2011 Davie Allan Musician, Guitarist, Early Rock 09/25/2011 Fred Allard Amp Sales, Inc, Founder 12/08/2010 John Allegrezza Allegrezza Piano, President 10/10/2012 Andy Allen Luthier 07/11/2017 Richard (RC) Allen Luthier, Friend of Paul A. -

Stephan Foust and Karen Krieger Oral History Collection 12-051

Manuscript Collection THE CENTER FOR POPULAR MUSIC MIDDLE TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY, MURFREESBORO, TN Stephan Foust and Karen Krieger Oral History Collection 12-051 Accession Numbers 12-051 Type of Material Manuscript materials, Iconographic items, Sound recordings Physical Description 1.5 Linear feet, including: Sound recordings including 15 cassette tapes Video recordings including 10 VHS-C tapes and 11 DVDs Manuscripts including papers and photographs Dates October 26, 1996 to June 24, 1998 Restrictions All materials in this collection are subject to standard national and international copyright laws. Center staff are able to assist with copyright questions for this material. Provenance and Acquisition Information This collection was delivered and donated to the Center by Stephan Foust on May 6, 2013. Arrangement The original arrangement scheme for the collection was maintained during processing. The collection is divided into two collections: Audio/Visual Collection that includes ten series based on the interviewed individuals and related materials; and Manuscript Collection that is organized by artist. Subject/Index Terms 1 / 6 Stephan Foust and Karen Krieger Oral History Collection 12-051 Foust, Stephan Krieger, Karen Allman, Gregg, 1947- Cavaliere, Felix Hornsby, Bruce Joel, Billy John, Dr., 1940- Kooper, Al Leavell, Chuck McDonald, Michael, 1952- Winwood, Steve, 1948- Wynans, Reese Music--Instruction and study. Keyboard artist Keyboard instrument music. Blues (Music) Rock music Piano music (Blues) Piano music (Rock) Agency History/Biographical Sketch Stephan Foust and Karen Krieger are both heavily involved in education and music in the Nashville area. Foust is a writer, video producer, and journalist. He has won several Associated Press and United Press International Awards for his work in television news. -

Come Together: Fifty Years of Abbey Road Schedule and Abstracts

Come Together: Fifty Years of Abbey Road An academic conference hosted by the University of Rochester Institute for Popular Music and The Eastman School of Music September 27-29, 2019 Rochester, New York Schedule and Abstracts 2 Come Together: Fifty Years of Abbey Road An academic conference hosted by the University of Rochester Institute for Popular Music and the Eastman School of Music Abstracts Friday, September 27 9:00-10:30 Session 1 (Hatch Recital Hall), Chair: Katie Kapurch (Texas State University) Walter Everett (University of Michigan) “The Mellow Depth of Melody in Abbey Road” This talk is in response to a request from Mark Lewisohn this past summer for a comment on the abundance of melody in Abbey Road. I soon recognized this as a very useful approach to the album, which overflows with songs that relate to each other in both parallel and contrasting ways, particularly in terms of melodic content. Not only do featured lead vocal lines possess their own mature beauty, but both vocal and instrumental countermelodies—a crucial trait of middle-period Beatles—hold striking significance. I plan to discuss: how ornamentation varies repetitions, the ways in which a song's formal structure impacts melodic growth, the role of rhythm in uniting melodic motives across the LP, and the tunes within tunes in considering structural aspects of melody. Kenneth Womack (Monmouth University) “The Long One: Producing Abbey Road with George Martin and the Beatles” This paper traces the genesis of the Long One, the symphonic suite that closes Abbey Road— and, in many ways, the Beatles’ career. -

Jeff Young Pure Herringbone

INFORMATION FÜR MEDIENPARTNER JEFF YOUNG PURE HERRINGBONE Music that comes from the heart and touches the soul Before “Choose Your Own Unknown”, the brand-new al- bum by renowned singer/songwriter and internationally acclaimed keyboardist Jeff Young arrives at the physical and digital stores in March 2016, let’s take a moment to look back at the story so far. A look back at the year 2009, when JEFF YOUNG wrote the musical “One Hit Away”, featuring songs which were released in the US on a CD entitled “Pure Herringbone” in 2010 and will also be available Europe soon. Songs from a musical? The mere notion may seem a little perplexing to some. But anybody prepared to listen to this outstanding album with an open mind will be pleasantly surprised: “Pure Herringbone” features brilliant songs, expertly honed musical gems from the soul, blues, pop, jazz and rock genres – every one of them a unique work of art, with the minor difference that this time around they tell a great story. In his own inimitable style, Jeff Young chronicles the story of the fictitious musician Pure Herringbone, who dreams of changing his whole life with one single hit record – in other words, to experience many a musician’s dream. The songs on his album are about vision and ambition, adversities and obstacles and the machinations of the music industry. Jeff Young has written and recorded some fantastic material with great sensitivity and a lot of warmth. For Jeff Young himself, many his musical and professional dreams have already come true. The man with the divine soul voice is a sought-after keyboardist who has worked for international superstars such as Sting, Do- nald Fagen (Steely Dan), Alanis Morissette, Bruce Springsteen, Bonnie Raitt, Curtis Stigers and many others. -

Music Major Handbook 2018-2019

This handbook is designed to provide the information you will need to complete your music degree successfully. Inside, you will find information about performance opportunities, use of the concert hall and recording studios, advising tips, as well as a faculty directory. MUSIC MAJOR HANDBOOK 2018-2019 ii Table of Contents Faculty/Staff Directory ....................................................................2-3 Performance Related Information Performance Opportunities ......................................................4-5 Student Recitals ..........................................................................6 Concert Hall, Music Box, and Concert Policies ......................7 Collaborative Piano Guidelines ................................................8 Historical Keyboard Usage Forum...........................................9-10 Junior-Senior Recital Request Form .......................................11-12 Departmental/Honors Recital Nomination Form ...................13-14 Audio/Video Services .................................................................15 Use of UMBC Space, Equipment, and Name ..........................15 Academics Advising Reminders ...................................................................16-17 Music 191 – Recital Preparation ..............................................18 Changing Private Instructors ...................................................18 Jury Information ........................................................................18 Jury Requirements.....................................................................19-23 -

OH Completed List

OH Completed List Page 1 of 92 3/2/2021 11:29:59AM First Name Last Name Title Interview Date Joe Abbati Frost School of Music, Professor 2019-11-17 Yoshiharu Abe TEAC, Engineer and Innovator d 2006-10-14 Norbert Abel Abel Hammer Company, President 2015-07-17 David L. Abell David L. Abell Fine Pianos, Founder d 2005-10-18 Susan Aberbach Hill & Range Songs Inc., President 2012-11-14 Lester Abrams Songwriter 2015-02-02 Richard Abreau Music Village, Advocate 2013-07-03 Gus Acevedo International House of Music, Founder 2012-01-20 Ken Achard Peavey Electronics Corporation, Sales Director UK 2005-07-11 Tony Acosta Luthier Strings, Founder d 2007-01-17 Cliff Acred Amro Music, Band Instrument Repair 2013-07-15 Arthur Adams Songwriter, Musician 2011-09-25 Edna Adams World Wide Music, Former Sales Executive 2010-04-16 Mike Adams Sound Image, Chief Engineer 2018-03-28 Paul Adams Piano Technician 2015-07-17 Mike Adams Moog Music, President 2010-01-13 Chris Adamson Tour Manager 2019-01-25 Leo Adelman Musician 2019-05-14 Hawley Ades Shawnee Press, Music Arranger d 2007-06-10 Henry Adler Henry Adler Music, Founder d 2007-10-19 Dominique Agnew NAMM, Former Director Trade Show Sales 2009-08-13 Charles Ahlers Anaheim Visitor and Convention Bureau, President 2013-01-25 Chuck Ainlay Recording Engineer 2019-07-16 Don Airey Musician, Keyboardist 2014-09-29 Takehiko Akaboshi Japan Music Volunteer Assoc., Former Chairman d 2006-10-14 Bulent Akbay Istanbul Mehmet, Product Specialist 2013-04-11 Joy Akerman NAMM Foundation's Museum of Making Music, 2007-11-30 Docent