Multiplicity in Everett's Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

God and Contrasting Interpretations of Quantum Theory

S & CB (2005), 17, 155–175 0954–4194 ROGER PAUL Relative State or It-from-Bit: God and Contrasting Interpretations of Quantum Theory In this article I explore theological implications of two contrasting interpretations of quantum theory: the Relative State interpretation of Hugh Everett III, and the It-from-Bit proposal of John A. Wheeler. The Relative State interpretation considers the Universal Wave Function to be a complete description of reality. Measurement results in a branching process that can be interpreted in terms of many worlds or many minds. I discuss issues of the identity of observers in a branching universe, the ways God may interact with the deterministic, isolated quantum universe and the relative nature of salvation history from a perspective within a branch. In contrast, irreversible, elementary acts of observation are considered to be the foundation of reality in the It-from-Bit proposal. Information gained through observer-participancy (the ‘bits’) constructs the fabric of the physical universe (‘it’), in a self-excited circuit. I discuss whether meaning, including religious faith, is a human construct, and whether creation is co- creation, in which divine power and supremacy are limited by the emergence of a participatory universe. By taking these two contrasting interpretations of quantum theory seriously, I hope to show that the interpretation of quantum mechanics we start from matters theologically. Key words: Quantum theory, theology, relative state, many worlds, it-from- bit, observer-participancy, human identity, divine simplicity, co-creation, salvation history. Theological thinking about quantum mechanics has tended to focus on the issue of Special Divine Action in relation to the uncertainty principle and quan- tum measurement.1 Inevitably, this work has been inconclusive, but has nev- ertheless succeeded in opening up the discussion. -

Life and Quantum Interconnectedness

Life and Quantum Interconnectedness Husin Alatas Theoretical Physics Division, Department of Physics, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, IPB University; Center for Transdisciplinary and Sustainability Sciences, IPB University Presented at the Afternoon Discussion on Redesigning the Future (ADReF), CTSS-IPB University, June 30th 2020 Outline... Structure of Fundamental Matter Quantum World and its Weirdness Quantum Interpretations Life and Quantum Interconnectedness Disclaimer!… I am a theoretical physicist, not a philosopher… I have been trained as a reductionist, but now I am trying to be an integralist… Physics… Mainly about understanding nature phenomena based on OBSERVATION and MEASUREMENT conducted through scientific method Theoretical Physics?… Theoretical physics is a branch of physics that deals with rationalization, explanation, and prediction of phenomena in natural systems which is developed based on the combination of mathematics, abstraction, imagination, and intuition. Conducted research mainly based on curiosity with sky as its limit. Albert Einstein… “Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution”… Albert Szent-Györgyi… “As scientists attempt to understand a living system, they move down from dimension to dimension, from one level of complexity to the next lower level. I followed this course in my own studies. I went from anatomy to the study of tissues, then to electron microscopy and chemistry, and finally to quantum mechanics. This downward journey through the scale of dimensions has its irony, for in my search for the secret of life, I ended up with atoms and electrons, which have no life at all. Somewhere along the line life has run out through my fingers. -

Black Hole Entropy, the Black Hole Information Paradox, and Time Travel Paradoxes from a New Perspective

Black hole entropy, the black hole information paradox, and time travel paradoxes from a new perspective Roland E. Allen Physics and Astronomy Department, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX USA [email protected] 1 Black hole entropy, the black hole information paradox, and time travel paradoxes from a new perspective Relatively simple but apparently novel ways are proposed for viewing three related subjects: black hole entropy, the black hole information paradox, and time travel paradoxes. (1) Gibbons and Hawking have completely explained the origin of the entropy of all black holes, including physical black holes – nonextremal and in 3-dimensional space – if one can identify their Euclidean path integral with a true thermodynamic partition function (ultimately based on microstates). An example is provided of a theory containing this feature. (2) There is unitary quantum evolution with no loss of information if the detection of Hawking radiation is regarded as a measurement process within the Everett interpretation of quantum mechanics. (3) The paradoxes of time travel evaporate when exposed to the light of quantum physics (again within the Everett interpretation), with quantum fields properly described by a path integral over a topologically nontrivial but smooth manifold. Keywords: Black hole entropy, information paradox, time travel 1. Introduction The three issues considered in this paper have all been thoroughly discussed by many of the best theorists for several decades, in hundreds of extremely erudite articles and a large number of books. Here we wish to add to the discussion with some relatively simple but apparently novel ideas that involve, first, the interpretation of the Euclidean path integral as a true thermodynamic partition function, and second, the Everett interpretation of quantum mechanics. -

Adobe Acrobat PDF Document

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH of HUGH EVERETT, III. Eugene Shikhovtsev ul. Dzerjinskogo 11-16, Kostroma, 156005, Russia [email protected] ©2003 Eugene B. Shikhovtsev and Kenneth W. Ford. All rights reserved. Sources used for this biographical sketch include papers of Hugh Everett, III stored in the Niels Bohr Library of the American Institute of Physics; Graduate Alumni Files in Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University; personal correspondence of the author; and information found on the Internet. The author is deeply indebted to Kenneth Ford for great assistance in polishing (often rewriting!) the English and for valuable editorial remarks and additions. If you want to get an interesting perspective do not think of Hugh as a traditional 20th century physicist but more of a Renaissance man with interests and skills in many different areas. He was smart and lots of things interested him and he brought the same general conceptual methodology to solve them. The subject matter was not so important as the solution ideas. Donald Reisler [1] Someone once noted that Hugh Everett should have been declared a “national resource,” and given all the time and resources he needed to develop new theories. Joseph George Caldwell [1a] This material may be freely used for personal or educational purposes provided acknowledgement is given to Eugene B. Shikhovtsev, author ([email protected]), and Kenneth W. Ford, editor ([email protected]). To request permission for other uses, contact the author or editor. CONTENTS 1 Family and Childhood Einstein letter (1943) Catholic University of America in Washington (1950-1953). Chemical engineering. Princeton University (1953-1956). -

The Nine Lives of Schrödinger's

University of London Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine Department of Physics The Nine Lives of Schr¨odinger’s Cat On the interpretation of non-relativistic quantum mechanics Zvi Schreiber Rakach Institute of Physics The Herbrew University Givaat Ram Jerusalem 91904 e-mail [email protected] arXiv:quant-ph/9501014v5 27 Jan 1995 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science of the University of London October 1994 Contents I Introduction 1 I.1 Introduction 2 I.1.1 A brief history of quantum mechanics .................. 2 I.1.2 The interpretational issues ........................ 4 I.1.3 Outline of thesis .............................. 6 II Quantum mechanics 7 II.1 Formulation of quantum mechanics 8 II.1.1 Dirac notation ............................... 8 II.1.2 Systems and observables ......................... 8 II.1.3 Formulation ................................ 9 II.1.4 The Heisenberg picture .......................... 14 II.1.5 Quantisation and the Schr¨odinger representation ........... 15 II.1.6 Mixed states and the density matrix .................. 17 II.1.7 The Logico-algebraic approach ...................... 21 II.1.8 Spin half .................................. 24 II.2 Histories 25 III Interpretation 33 III.1 The Orthodox interpretation 34 III.2 Bohr’s interpretation 40 III.3 Mind causes collapse 46 III.4 Hidden variables 53 III.5 Many-worlds interpretation 62 III.6 Many-minds interpretation 69 III.7 Bohm’s interpretation 73 III.8 Decoherent histories (Ontology) 82 III.9 Decoherent histories (Epistemology) 89 IV Conclusion 94 IV.1 Conclusion 95 Part I Introduction The most remarkable aspect of quantum mechanics is that it needs interpretation. -

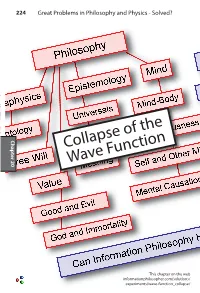

Collapse of the Wave Function

224 Great Problems in Philosophy and Physics - Solved? Chapter 20 Chapter Collapse of the Wave Function This chapter on the web informationphilosopher.com/solutions/ experiments/wave-function_collapse/ Collapse 225 Collapse of the Wave Function The probability amplitude wave function in quantum mechan- ics and its indeterministic collapse during a measurement is with- out doubt the most controversial problem in physics today. Of the several “interpretations” of quantum mechanics, more than half deny the collapse of the wave function1. Some of these deny quan- tum “jumps” and even the existence of particles! So it is very important to understand the importance of what Paul Dirac called the projection postulate in quantum mechan- ics. The “collapse of thewave function” is also known as the “reduction of the wave packet.” This usually describes the change from a system that can be seen as having many possible quantum states (Dirac’s principle of superposition) to its randomly being found in only one of those possible states. Although the collapse is historically thought to be caused by a measurement, and thus dependent on the role of a conscious observer2 in preparing the experiment, collapses can occur when- ever quantum systems interact (e.g., collisions between particles) or even spontaneously (radioactive decay). The claim that a conscious observer is needed to collapse the Chapter 20 Chapter wave function has injected a severely anthropomorphic element into quantum theory, suggesting that nothing happens in the universe except when physicists are making measurements. An extreme example is Hugh Everett III’s Many Worlds theory, which says that the universe splits into two nearly identical uni- verses whenever a binary measurement is made. -

Typicality in Pure Wave Mechanics

TYPICALITY IN PURE WAVE MECHANICS JEFFREY A. BARRETT Abstract. Hugh Everett III's pure wave mechanics is a deterministic physical theory with no probabilities. He nevertheless sought to show how his theory might be understood as making the same statistical predictions as the stan- dard collapse formulation of quantum mechanics. We will consider Everett's argument for pure wave mechanics, how it depends on the notion of branch typicality, and the relationship between the predictions of pure wave mechanics and the standard quantum probabilities. 1. introduction Hugh Everett III (1956; 1957) presented pure wave mechanics, sometimes re- ferred to as the many-worlds interpretation, as a preferable alternative to both the Copenhagen and standard von Neumann-Dirac collapse formulations of quantum mechanics. While pure wave mechanics is a deterministic physical theory with no probabilities, Everett sought to show how the theory might be understood as mak- ing the standard quantum statistical predictions as appearances to observers who were themselves described by the theory. The key step in his argument was to show that there was a sense in which almost all quantum-mechanical branches of the total state will describe sequences of measurement results that are compatible with the standard statistical predictions of quantum mechanics. We will consider his argument, how it depends on the notion of branch typicality, and the relation- ship between the predictions of pure wave mechanics and the standard quantum probabilities. Everett began his presentation of pure wave mechanics with a discussion of the difficulties that John von Neumann's (1932; 1955) formulation of P. A. -

Schrödinger's Cape: the Quantum Seriality of the Marvel Multiverse William Proctor, University of Bournemouth, UK. on The

Schrödinger’s Cape: The Quantum Seriality of the Marvel Multiverse William Proctor, University of Bournemouth, UK. On the surface, quantum physics and narrative theory are not easy bedfellows. In fact, some may argue that the two fields are incommensurable paradigms and any attempt to prove otherwise would be a foolhardy endeavour, more akin to intellectual trickery and sleight-of- hand than a prism with which to view narrative systems. Yet I find myself repeatedly confronted by these two ostensibly incompatible theories converging as I explore the vast narrative networks associated with fictional world-building -- most notably those belonging to comic book multiverses of Marvel and DC Comics which, Nick Lowe argues “are the largest narrative constructions in human history (exceeding, for example, the vast body of myth, legend and story that underlies Greek and Latin literature)” (Kaveney, 25). Contemporary quantum theory postulates that the universe is not a singular body progressing linearly along a unidirectional spatiotemporal pathway – as exponents of the Newtonian classic physics model believe – but, rather, a multiverse comprised of alternate worlds, parallel dimensions and multiple timelines. Both Marvel and bête noire DC Comics embrace the multiverse concept that allows multiple iterations, versions and reinterpretations of their character populations to co-exist within a spatiotemporal framing principle that shares remarkable commonalities with the quantum model. Where Marvel and DC deviate from one another, however, is that the latter utilises the conceit as an intra-medial model for its panoply of comic books; whereas, conversely, the Marvel multiverse functions as a transmedia firmament that encapsulates an entire catalogue within its narrative rubric, a strategy that is analogous with the quantum paradigm. -

The Quantum World the Disturbing Theory at the Heart of Reality

The Quantum World The disturbing theory at the heart of reality NEW SCIENTIST 629462_The_Quant_World_Book.indb 3 3/11/17 12:37 PM First published in Great Britain in 2017 by John Murray Learning. An Hachette UK company. Copyright © New Scientist 2017 The right of New Scientist to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by it in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Database right Hodder & Stoughton (makers) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographic rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, John Murray Learning, at the address below. You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: a catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: on file. ISBN: 978 1 47362 946 2 eISBN: 978 1 47362 947 9 1 The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that any website addresses referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher and the author have no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content will remain relevant, decent or appropriate. -

John Archibald Wheeler Wheeler’S Early Work in Gravitation Physics

Gen Relativ Gravit (2009) 41:675–677 DOI 10.1007/s10714-009-0777-y OBITUARY In memoriam: John Archibald Wheeler Wheeler’s early work in gravitation physics Charles W. Misner Published online: 6 March 2009 © The Author(s) 2009. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com John Archibald Wheeler (9 July 1911–13 April 2008) was a dominant figure in the GRG area from the time he taught his first course in General Relativity at Princeton in the spring of 1952 until his focus changed as he moved to Texas in 1976. But there were important connections between his earlier nuclear physics work and his later quantum fundamentals work. His earlier work, including the introduction of the S-matrix and the application of the nuclear liquid drop model to fission, enabled him to publish (and have read) daring ideas about the possibilities of implausible objects speculated to be consistent with the Einstein–Maxwell equations. His work on neutron star stability enabled him to combine the (then out-of-fashion) Einstein theory of grav- ity with his acknowledged expertise in nuclear forces, thus brushing GR with some of the respectability of nuclear physics. And then, during his daring conservativism phase of GR exploration, he supported a Ph.D. for Hugh Everett who had daring ideas about believing the Schrödinger equation at macroscopic levels. In this Wheeler was intrigued by the need to be able to talk about the wave function of the universe in order to study the very early Universe where he felt quantum mechanics could not be ignored. -

The Tao of It and Bit

Fourth prize in the FQXi's 2013 Essay Contest `It from Bit, or Bit from It?' This version appeared as a chapter in the collective volume It From Bit or Bit From It? Springer International Publishing, 2015. pages 51-64. The Tao of It and Bit To J. A. Wheeler, at 5 years after his death. Cristi Stoica E m a i l : [email protected] Abstract. The main mystery of quantum mechanics is contained in Wheeler's delayed choice experiment, which shows that the past is determined by our choice of what quantum property to observe. This gives the observer a par- ticipatory role in deciding the past history of the universe. Wheeler extended this participatory role to the emergence of the physical laws (law without law). Since what we know about the universe comes in yes/no answers to our interrogations, this led him to the idea of it from bit (which includes the participatory role of the observer as a key component). The yes/no answers to our observations (bit) should always be compatible with the existence of at least a possible reality { a global solution (it) of the Schr¨odingerequation. I argue that there is in fact an interplay between it and bit. The requirement of global consistency leads to apparently acausal and nonlocal behavior, explaining the weirdness of quantum phenomena. As an interpretation of Wheeler's it from bit and law without law, I discuss the possibility that the universe is mathematical, and that there is a \mother of all possible worlds" { named the Axiom Zero. -

Everett's Multiverse and the World As Wavefunction

quantum reports Article Everett’s Multiverse and the World as Wavefunction Tappenden Paul 44 bd. Nungesser, 13014 Marseille, France; [email protected] Received: 1 September 2019; Accepted: 9 September 2019; Published: 12 September 2019 Abstract: Everett suggested that there’s no such thing as wavefunction collapse. He hypothesized that for an idealized spin measurement the apparatus evolves into a superposition on the pointer basis of two apparatuses, each displaying one of the two outcomes which are standardly thought of as alternatives. As a result, the observer ‘splits’ into two observers, each perceiving a different outcome. There have been problems. Why the pointer basis? Decoherence is generally accepted by Everettian theorists to be the key to the right answer there. Also, in what sense is probability involved, when all possible outcomes occur? Everett’s response to that problem was inadequate. A first attempt to find a different route to probability was introduce by Neil Graham in 1973 and the path from there has led to two distinct models of branching. I describe how the ideas have evolved and their relation to the concepts of uncertainty and objective probability. Then I describe the further problem of wavefunction monism, emphasized by Maudlin, and make a suggestion as to how it might be resolved. Keywords: everett interpretation; many worlds interpretation; everettian quantum mechanics; quantum probability; wavefunction realism There may be a way to maintain a monistic wavefunction ontology, but it is certainly not trivial to see what that way is [1], p. 129 and original emphasis. 1. Two Concepts of Branching There are two ways to model branching, both of which can be illustrated by the waters of a river being distributed into the streams of an estuary.