Traumatic Glaucoma in Children 1Savleen Kaur, 2Sushmita Kaushik, 3Surinder Singh Pandav

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traumatic Glaucoma: an Overview

Indian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2020;6(1):1–2 Content available at: iponlinejournal.com Indian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology Journal homepage: www.innovativepublication.com Editorial Traumatic glaucoma: An overview Rajendra Prakash Maurya1,* 1Regional Institute of Ophthalmology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India ARTICLEINFO © 2020 Published by Innovative Publication. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND Article history: license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) Received 11-03-2020 Accepted 12-03-2020 Available online 17-03-2020 of blunt trauma are (i) Trabecular meshwork disruption, Dear Friends (ii) Hyphaema: Accumulation of blood in the anterior chamber leads to obstruction of the trabecular meshwork Season’s Greeting!! with erythrocytes, fibrin, platelets and other inflammatory It is my humble privilege to present the special issue debris lead to prolonged increase in the IOP. 2 (iii) of IJCEO after successful journey of five years. This Inflammation: Trauma may also lead to direct inflammation issue of IJCEO has several interesting articles on vision of the trabecular meshwork (trabeculitis) causing decrease threatening morbidity, Glaucoma particularly on diagnosis in aqueous outflow. (iv) Choroidal hemorrhage: causing and management of primary glaucoma. a mass effect in the posterior segment leading to forward Traumatic glaucoma (TG) refers to a heterogeneous displacement of the lens-iris diaphragm and leads to acute group of post-traumatic secondary glaucoma with varying angle closure glaucoma. The pathophysiology of late underlying mechanisms. Traumatic glaucoma occurs onset TG are (i) Angle-Recession (tear which occurs commonly after mechanical injury of globe (blunt or between the longitudinal and circular layers of the ciliary penetrating injury). -

Doyne Lecture the Pathology of the Outflow System in Primary and Secondary Glaucoma

DOYNE LECTURE THE PATHOLOGY OF THE OUTFLOW SYSTEM IN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY GLAUCOMA W. R. LEE Glasgow On behalf of my specialty of ophthalmic pathology, I noted that since the contribution of Doyne himself, am indebted to the Master of the Oxford Congress few pathologists have been honoured. Professor for the invitation to present the Doyne Memorial Norman Ashton and the late Professor David Lecture on the pathology of the outflow system in Cogan were the only ophthalmic pathologists primary and secondary glaucoma. Although I regard included in the list. In 1960, Professor Ashton3 the Doyne Lecture as an awesome responsibility, it chose to lecture on the pathology of the outflow has been an enjoyable exercise in preparing for it to channels in glaucoma and I was interested to see that go through the contributions of previous Doyne in the final paragraph of his text he wrote 'no doubt lecturers and to read the remarks made by those who this topic will again be chosen by a Doyne Lecturer'. knew Doyne personally. From the various very Thus it is appropriate that the problem of glaucoma distinguished Doyne lecturers who have preceded should again be addressed by a pathologist some 35 me, I sense that the ethos of this lecture is that years later. In this lecture I have drawn freely on the speculation is an integral requirement of the speaker. research material which my colleagues and I have This is not so easy for a pathologist, but I hope that been studying in Glasgow for the past 25 years and I some of the text will be sufficiently controversial to have used this to re-interpret conventional morphol stimulate further research work. -

Diagnosis and Management of Vitreous Hemorrhage

American Academy of Ophthalmology OCAL CLINICAL MODULES FOR OPHTHALMOLOGISTS VOLUME XVIII NUMBER 10 DECEMBER 2000 (SECTION 1 OF 3) Diagnosis and Management of Vitreous Hemorrhage Andrew W. Eller, M.D. Reviewers and Contributing Editors Editors for Retina and Vitreous: Dennis M. Marcus, M.D. Paul Sternberg, Jr., M.D. Basic and Clinical Science Course Faculty, Section 12: Harry W. Flynn, Jr., M.D. Consultants Practicing Ophthalmologists Advisory Committee Dennis M. Marcus, M.D. for Education: Edgar L. Thomas, M.D. Rick D. Isernhagen, M.D. l]~ THE fOUNDATION [liO) LIFELONG EDUCATION ~OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY FOR THE OPHTHALMOLOGIST OF OPHTHALMOLOGY Focal Points Editorial Review Board Diagnosis and Management of Michael W Belin, M.D., Albany, NY; Editor-in-Chief; Cornea, Vitreous Hemorrhage External Disease & Refractive Surgery; Optics & Refraction • Charles Henry, M.D., Little Rock, AR; Glaucoma • Careen Yen Lowder, M.D., Ph.D., Cleveland , OH; Ocular Inflammation & INTRODUCTION Tumors • Dennis M. Marcus, M .D., Augusta, GA; Retina & Vitreous • Jeffrey A. Nerad, M.D., Iowa City, IA; Oculoplastic, PATHOGENESIS Lacrimal & Orbital Surgery • Priscilla Perry, M.D., Monroe, Neovascularization of Retina and Disc LA; Cataract Surgery; Liaison for Practicing Ophthalmologists Rupture of a Normal Retinal Vessel Advisory Committee for Education • Lyn A. Sedwick, M.D., Diseased Retinal Vessels Orlando, FL; Neuro-Ophthalmology • Kenneth W. Wright, M.D., Los Angeles, CA; Pediatric Ophthalmology & Strabismus Extension Through the Retina CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS Focal Points Staff History Susan R. Keller, Managing Editor • Kevin Gleason and Victoria Vandenberg, Medical Editors Ocular Examination DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES Clinical Education Secretaries and Staff Thomas A. Weingeist, Ph.D., M.D., Iowa City, IA; Senior B-Scan Ultrasound Secretary • Michael A. -

Ghost Cell Glaucoma After Intravitreous Injection of Ranibizumab in Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy Jun Xu, Meng Zhao*, Ji Peng Li and Ning Pu Liu

Xu et al. BMC Ophthalmology (2020) 20:149 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-020-01422-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Ghost cell glaucoma after intravitreous injection of ranibizumab in proliferative diabetic retinopathy Jun Xu, Meng Zhao*, Ji peng Li and Ning pu Liu Abstract Background: The development of ghost cell glaucoma in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) after intravitreous injection (IV) was rare. Here we reported a series of patients with PDR who received Intravitreous Ranibizumab (IVR) and developed ghost cell glaucoma and analyzed the potential factors that might be related to the development of ghost cell glaucoma. Methods: Retrospective case series study. The medical records of 71 consecutive eyes of 68 PDR patients who received vitrectomy after IVR from January 2015 to January 2017 were reviewed. The development of ghost cell glaucoma after IVR was recorded. Characteristics of enrolled patients were retrieved from their medical charts. Factors associated with ghost cell glaucoma were compared between eyes with the development of ghost cell glaucoma and eyes without the development of ghost cell glaucoma. Variables were further enrolled in a binary backward stepwise logistic regression model, and the model that had the lowest AIC was chosen. Results: There were 8 out of 71 eyes of the PDR patients developed ghost cell glaucoma after they received IVR. The interval between detection of elevation of intraocular pressure (IOP) and IV ranged from 0 to 2 days. Among them, after IVR, there were two eyes had IOP greater than 30 mmHg within 30 min, four eyes showed normal IOP at 30 min, and then developed ghost cell glaucoma within 1 day, two eyes developed ghost cell glaucoma between 24 and 48 h. -

Major Review

SURVEY OF OPHTHALMOLOGY VOLUME 47 • NUMBER 4 • JULY–AUGUST 2002 MAJOR REVIEW Management of Traumatic Hyphema William Walton, MD, Stanley Von Hagen, PhD, Ruben Grigorian, MD, and Marco Zarbin, MD, PhD Institute of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey, USA Abstract. Hyphema (blood in the anterior chamber) can occur after blunt or lacerating trauma, after intraocular surgery, spontaneously (e.g., in conditions such as rubeosis iridis, juvenile xanthogranu- loma, iris melanoma, myotonic dystrophy, keratouveitis (e.g., herpes zoster), leukemia, hemophilia, von Willebrand disease, and in association with the use of substances that alter platelet or thrombin function (e.g., ethanol, aspirin, warfarin). The purpose of this review is to consider the management of hyphemas that occur after closed globe trauma. Complications of traumatic hyphema include increased intraocular pressure, peripheral anterior synechiae, optic atrophy, corneal bloodstaining, secondary hemorrhage, and accommodative impairment. The reported incidence of secondary ante- rior chamber hemorrhage, that is, rebleeding, in the setting of traumatic hyphema ranges from 0% to 38%. The risk of secondary hemorrhage may be higher in African-Americans than in whites. Secondary hemorrhage is generally thought to convey a worse visual prognosis, although the outcome may depend more directly on the size of the hyphema and the severity of associated ocular injuries. Some issues involved in managing a patient with hyphema are: use of various medications (e.g., cycloplegics, systemic or topical steroids, antifibrinolytic agents, analgesics, and antiglaucoma medications); the patient’s activity level; use of a patch and shield; outpatient vs. inpatient management; and medical vs. surgical management. -

Ophthalmic Care of the Combat Casualty Chapter 11 Glaucoma

Glaucoma Associated With Ocular Trauma Chapter 11 GLAUCOMA ASSOCIATED WITH OCULAR TRAUMA NEIL T. CHOPLIN, MD* INTRODUCTION GLAUCOMA OCCURRING EARLY FOLLOWING OCULAR TRAUMA Inflammation Alterations in Lens Position Hyphema Phacoanaphylactic Glaucoma Increased Episcleral Venous Pressure Glaucoma Following Chemical Injuries Glaucoma Due to Trauma to Nonocular Structures GLAUCOMA OCCURRING LATE FOLLOWING OCULAR TRAUMA Steroid-Induced Glaucoma Secondary Angle Closure Ghost Cell (Hemolytic) Glaucoma Posttraumatic Angle Deformity (Angle Recession) Chemical Injuries Glaucoma Following Penetrating and Perforating Injuries Siderosis Bulbi TREATMENT SUMMARY *Captain, US Navy (Ret); Eye Care of San Diego, 3939 Third Avenue, San Diego, California 92103; Adjunct Clinical Professor of Surgery, Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, 4301 Jones Bridge Road, Bethesda, Maryland 20814-4799; formerly, Chairman, Depart- ment of Ophthalmology, Naval Medical Center, San Diego, California 185 Ophthalmic Care of the Combat Casualty INTRODUCTION The definition of glaucoma has undergone con- the eye following trauma can result in significant siderable change in the last 20 years. As commonly elevations of IOP, it is presumed that optic nerve used today, glaucoma refers to a diverse group of damage will occur if the pressure remains high eye disorders characterized by progressive loss of enough long enough, even if the optic nerve is nor- axons from the optic nerve, resulting in loss of vi- mal at the time of presentation. sual function as manifested in the visual field.1 The Although glaucomatous optic neuropathy may structural changes in the optic nerve head are rec- take some time to develop, elevated IOP after ocu- ognizable, and the patterns of visual field damage lar trauma can occur immediately after the injury are characteristic but not specific. -

Glaucoma.Pdf

ENTITLEMENT ELIGIBILITY GUIDELINES GLAUCOMA MPC 00640 ICD-9 365.1 and 365.2 DEFINITION Glaucoma is a medical condition referring to a group of diseases that has certain common features. These include an intraocular pressure (IOP) too high for the continued health of the eye, cupping and atrophy of the optic nerve head, and loss of visual field. DIAGNOSTIC STANDARD A diagnosis by a qualified opthalmologist is required. Investigations should include visual acuity, visual field (perimetry), and intraocular pressure (tonometry). Reports must be submitted with the application. ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY The eye has 3 chambers, the anterior chamber in front of the iris, the posterior chamber between the iris and the lens, and the vitreous chamber behind the lens. Intraocular pressure is maintained by a balance between inflow and outflow of the aqueous humour, the fluid which nourishes the transparent structures of the eye. Aqueous humour is produced and secreted by the ciliary body, a gland behind the iris of the eye. Aqueous humour enters the anterior chamber of the eye through the pupil, and leaves by passing through the trabecular meshwork in the iridocorneal angle of the anterior chamber and back into venous circulation through the canal of Schlemm. A number of classification schemes for the glaucomas have been proposed. They are based on the age of the person (infantile, juvenile, adult), the site of obstruction to aqueous outflow (pre-trabecular, trabecular, post-trabecular), the tissue principally involved (e.g. glaucoma caused by diseases of the lens), and etiology. Although each of these systems has value, the classification scheme that separates angle closure from open angle glaucoma has been used most widely, because it focuses on pathophysiology and points to proper clinical management. -

Glaucoma Pearls Surgery Videos Medical Management

GLAUCOMA NUTS AND BOLTS & SECONDARY GLAUCOMAS Jason Ahee, MD Marcos Reyes, MD Dixie Ophthalmic Specialists TOPICS Glaucoma nuts and bolts Secondary Glaucoma Blood induced glaucoma All other secondary glaucomas If time allows Angle Closure Glaucomas Glaucoma Pearls Surgery videos Medical Management DISCLOSURES None! GLAUCOMA NUTS AND BOLTS Etiology of Glaucoma Glaucoma Evaluation Following Glaucoma Detecting glaucoma and progression WHAT IS GLAUCOMA? Retina Optic nerve •Glaucoma is an illness of the optic nerve, the nerve that carries the electrical signals for sight from the retina to the brain. WHAT IS GLAUCOMA? Optic nervehead The exact cause is not known, but usually glaucoma is associated with a higher than average pressure (low teens- low 20s) inside the eye, which damages the retinal ganglion cell axons. This damage is seen at the“optic nerve head‖. WHAT DAMAGES THE OPTIC NERVE IN GLAUCOMA? Pattern of Loss tells us the site of damage is at the optic nervehead Likely mechanism in high pressure glaucoma is a pressure-dependent blockade of axoplasmic transport Douglas Anderson 1974 Blockade of material (white) at the optic nerve head in a monkey with high eye pressure WHAT IS GLAUCOMA? There are many types of glaucoma, each named for special features. POAG or Primary Open Angle Glaucoma is a diagnosis of exclusion (i.e. look for other causes before labeling it POAG. Most are chronic conditions which can be treated but not cured, by lowering the eye pressure to prevent additional loss of sight. GLAUCOMA EVALUATION Current Medications Compliance Vision Pressure ( Applanation is gold standard ) Pachymetry Gonioscopy Anterior segment exam Optic Nerve cupping – structure Visual Field ( with BCVA ) - function Imaging (OCT or equivalent) - structure GLAUCOMA EVALUATION Gonio LOTS of normal angles, not just narrow ones. -

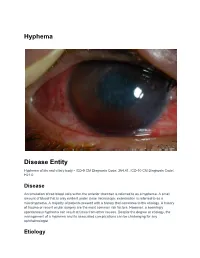

Hyphema Disease Entity

Hyphema Disease Entity Hyphema of iris and ciliary body - ICD-9 CM Diagnosis Code: 364.41, ICD-10 CM Diagnosis Code: H21.0 Disease Accumulation of red blood cells within the anterior chamber is referred to as a hyphema. A small amount of blood that is only evident under close microscopic examination is referred to as a microhyphema. A majority of patients present with a history that correlates to the etiology. A history of trauma or recent ocular surgery are the most common risk factors. However, a seemingly spontaneous hyphema can result at times from other causes. Despite the degree or etiology, the management of a hyphema and its associated complications can be challenging for any ophthalmologist. Etiology Hyphema can occur after blunt or lacerating trauma, after intraocular surgery, spontaneously (e.g., in conditions such as rubeosis iridis, juvenile xanthogranuloma, iris melanoma, myotonic dystrophy, keratouveitis (e.g., herpes zoster), leukemia, hemophilia, von Willebrand disease, and in association with the use of substances that alter platelet or thrombin function (e.g., ethanol, aspirin, warfarin).[1] Blunt trauma is the most common cause of a hyphema. Compressive force to the globe can result in injury to the iris, ciliary body, trabecular meshwork, and their associated vasculature. The shearing forces from the injury can tear these vessels and result in the accumulation of red blood cells within the anterior chamber. Hyphemas can also be iatrogenic in nature. Intraoperative or postoperative hyphema is a well known complication to any ocular surgery. Rarely, the placement of an intraocular lens within the anterior chamber can result in chronic inflammation, secondary iris neovascularization, and recurrent hyphemas, known as uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) syndrome.[2] This is a direct result of a malpositioned or rotating anterior chamber intraocular lens. -

Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Following Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma

CLINICOPATHOLOGIC REPORTS, CASE REPORTS, AND SMALL CASE SERIES SECTION EDITOR: W. RICHARD GREEN, MD ing the supraorbital notch revealed High-resolution MRI scans of the Lymphoepitheliomalike lymphoepithelioma with perineural orbits were obtained with conven- Carcinoma of the Orbit invasion. tional pulse sequences. They re- The ophthalmologic exam- vealed a multilocular cystlike mass in Lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma ination results revealed a best- the medial aspect of the right orbit (LELC) of the skin is an uncommon corrected visual acuity of 20/70 OD (Figure 1). Other imaging features cutaneous malignancy with the po- and 20/15 OS; the visual acuity had included fluid-fluid layers within the tential for distant metastasis.1 We de- been stable in the right eye since a lesion and peripheral enhancement. scribe a patient with LELC of the mid scleral buckle procedure for retinal A computed tomography scan of the forehead and an asymptomatic or- detachment was performed approxi- head and neck area that was ob- bital mass, which when biopsied mately 18 years prior to this presen- tained 6 weeks prior to the MRI scan proved to be a lymphoepithelioma- tation. The external examination re- did not show an orbital mass. like carcinoma (LELC). vealed quiet globes; the Hertel An orbital biopsy of the mass exophthalmometry measurement was performed through a modified Report of a Case. A 45-year-old man was 19 mm in each eye. Results of Lynch incision (superonasal orbi- was referred to the Ophthalmology the extraocular motility examina- totomy).2 The cystic mass was iden- Clinic at the University of Texas M. -

Chapter 7 Glaucoma Sehu Ch07.Qxd 03/17/2005 1:04 Page 136

Sehu_Ch07.qxd 03/17/2005 1:04 Page 135 135 Chapter 7 Glaucoma Sehu_Ch07.qxd 03/17/2005 1:04 Page 136 136 C HAPTER 7 “Glaucoma” is a generic term for a common group of and angle recession. The meriodonal fibres of the ciliary ocular diseases which, if untreated, can result in an irre- muscle insert into the scleral spur and the oblique layers versible loss of visual function. An inappropriate intraocular insert into the uveal layer of the trabecular meshwork. pressure linked to damage to the neuronal tissue in the The outer part of the trabecular meshwork lies within the optic nerve head is common to all forms of glaucoma. scleral sulcus (Figure 7.4) and the inner part fuses with the anterior face of the ciliary body. The trabecular mesh- work is formed by collagenous beams and plates lined by Classification endothelial cells. In conventional morphology, the trabecular meshwork is divided into three layers. The two innermost Glaucoma can be divided into five main subgroups: layers are the uveal and corneoscleral. The outermost 1 Congenital. layer is formed by the endothelial cells loosely arranged 2 Primary open. within mucopolysaccharides and collagen (Figures 7.4, 3 Primary closed. 7.5). The outermost layer is variously termed juxtacanalic- 4 Secondary open. ular (USA) or cribriform (Europe). 5 Secondary closed. Several functions are ascribed to the trabecular mesh- work. The juxtacanalicular layer provides resistance to maintain intraocular pressure and prevents reflux of blood Normal drainage anatomy from Schlemm’s canal. The endothelial cells lining the trabeculae within the meshwork have a capacity for Aqueous humour is produced in the ciliary processes by phagocytosis. -

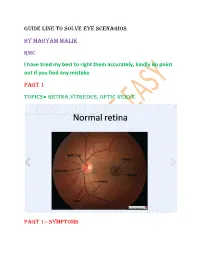

Guide Line to Solve Eye Scenarios by Maryam Malik

GUIDE LINE TO SOLVE EYE SCENARIOS BY MARYAM MALIK RMC I have tried my best to right them accurately, kindly do point out if you find any mistake PART 1 TOPICS= RETINA,VITREOUS, OPTIC NERVE PART 1= SYMPTOMS Most of the scenarios, we come across have the words LOSS OF VISION Now see the onset, is it SUDDEN or GRADUAL If its SUDDEN then the causes can be PAINFUL = TRACK (temporal arteritis, retrobulbar neuritis, Acute congestive glaucoma, corneal Hydrops in Keratoconus, keratitis) PAINLESS= any artery/venous occlusion at retina(CRAO/BRAO/CRVO/BRVO), Retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage Similarly GRADUAL will be having PAINFUL: Any inflammation in anterior part of eye like cornea (KERATITIS), Sclera (SCLERITIS), uveal (chronic IRIDOCYCLITIS) PAINLESS: DR-COCK= diabetic retinopathy,refractive error, cataract,optic atrophy, chronic open angle glaucoma, Keratoconus) Now a third category is TRANSIENT LOSS OF VISION (vision returns to normal within 24 hrs, usually in 1 hr) This is seen with either ischemia or any arterial condition Ventrobasilar insufficiciency Migraine (remember vasodilation of vessels leading to throbbing headache) Prodromal phase of CRAO Amaurosis fugax Giant cell arteritis Now the next thing is NIGHT BLINDNESS It can occur in Vit A deficiency Congenital Retinitis pigmentosa Peripheral cortical cataract Advanced PAOG DAY BLINDNESS It occurs with any type of CENTRAL OPACITY or RARELY absence of cones. Nuclear cataract Central corneal opacity Central vitreous opacity Congenital deficiency of cones Now FLOATERS