Lipstick and High Heels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O=Brien Shares Update on Dwc Night Squad

SUNDAY, 15 MARCH 2020 O=BRIEN SHARES UPDATE FRANCE CLOSES ALL NON-ESSENTIAL BUSINESSES, RACECOURSES REMAIN OPEN ON DWC NIGHT SQUAD FOR NOW At 8 p.m. Saturday evening, French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe announced stricter social distancing measures due to the coronavirus, and that all places non-essential to French living including restaurants, cafes, cinemas and clubs, will be closed beginning at midnight on Saturday, Jour de Galop reported. At this time, French racecourses, which are currently racing without spectators for the foreseeable future, will remain open. France Galop=s President Edouard de Rothschild and Managing Director Olivier Delloye both confirmed late Saturday evening to the JDG that racing will continue in Aclosed camera@ mode, but that the situation remains delicate. France=s PMU is affected by the closure, as all businesses where the PMU operates that does not also have the designation of cafJ, must be shuttered. Kew Gardens | Mathea Kelley Irish and German racing is also currently being conducted without spectators, while racing in the UK has proceeded very Coolmore=s Kew Gardens (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}), who snapped much as normal. All Italian racing has been suspended until at champion stayer Stradivarius (Ire) (Sea The Stars {Ire})=s winning least Apr. 3, as the entire country is in lock down. streak in the G2 Long Distance Cup on British Champions Day at Ascot in October, will make his 2020 bow in the $1.5-million G2 Dubai Gold Cup. The Aidan O=Brien trainee, who won the 2018 G1 Grand Prix de Paris as well as the G1 St Leger during his 3- year-old year, was never off the board in four starts last term, running second three timesBin the G3 Ormonde S. -

Plant Name Common Name Exposure Height Width Flower Color Zone

Plant name Common name Exposure Height Width Flower color Zone 8"Minnesota Mum Minnesota Mum sun 18-24" 4 Achillea 'Oertel's Rose' Yarrow sun 30" 30" orchid pink 3 Achillea 'Angelique' Yarrow sun 24" 24: deep red 3 Achillea 'Anthea' Yarrow sun 18" 18" light yellow 3 Achillea 'Apple Blossom' Yarrow sun 16-22' 16-22" lilac-pink 3 Achillea 'Colorado' Yarrow sun 24" 24" mixed pastel 3 Achillea 'Moonshine' Yarrow Sun 18-24" 18-24" Yellow Achillea 'Paprika' Yarrow sun 18" 18" red 3 Achillea 'Pink Grapefruit' Yarrow sun 28" 28" pink 4 Achillea 'Pomegranate' Yarrow sun 28" 28" magenta 4 Achillea 'Red Beauty' Yarrow sun 24" 24" red crimson 3 Achillea 'Red Velvet' Yarrow sun 30" 30" red 3 Achillea 'Schwellenberg' Yarrow sun 18-24" 18-24" yellow 4 Achillea 'Sunny Seduction' Yarrow sun 28" 28" yellow 4 Aconitum 'Blue Lagoon' Monkshood sun/pt shade 10-12" 8-10" Blue 4 Aconitum 'Blue Valley' Monkshood shade 36" 36" blue 4 Aconitum cammarum 'Stainless' Monkshood shade 40" 40" blue 4 Aconitum fischeri Azure Monkshood sun/pt sun 18-24" lav-blue 4 Adiantum pedatum Maiden Hair shade 18" 18" 3 Aegopodium 'Variegatum' Snow on Mt, Bishop's Cap sun/shade 10" 10" white 4 Aegopodium 'Variegatum' Snow on Mt, Bishop's Cap sun/shade 10" 10" white 3 Agastache foeniculum 'Blue For Anise Hyssop sun 36" 36" blue-violet 2 Ajuga Bugleweed sun/shade 4-6" 4-6" blue 3 Ajuga 'Bronze Beauty' Bugleweed sun/shade 4-6" 4-6" blue 3 Ajuga 'Bronze Beauty' Bugleweed sun/shade 4-6" 4-6" blue 3 Ajuga 'Burgundy Glow' Bugleweed sun/shade 6" 6" blue 3 Ajuga 'Burgundy Glow' Bugleweed sun/shade -

WASHOE COUNTY Permit Activity Report (Long Version) Permit Date: Issued 8/1/2017 to 8/31/2017

WASHOE COUNTY Permit Activity Report (Long Version) Permit Date: Issued 8/1/2017 to 8/31/2017 Permit #: 16-1028 Applied: 4/15/2016 Issued: 8/10/2017 Finaled: Type: Commercial New, Add or Tenant Improvement Permit Work: INSTALL NEW CELL TOWER FOR VERIZON WIRELESS Sub Type: New Commercial Address: 5849 MELARKEY WAY Class: 437 Commercial Remodel, Tenant Status: Issued Imp, Conversion City ID: Washoe # Units: 0 Value: $120,000.00 Total Fees: $3,078.74 Names: Sq Ft: 0 Parcel: 150-250-04 Balance Due: $0.00 OWNER MELARKEY ROSEMARY S 89511 CONTACT EWING BRETT / EPIC WIRELESS CONTRACTOR JEFF EBERT CONTRACTOR S T C NETCOM INC 11611 INDUSTRY AVE, FONTANA, CA, 92337 Permit #: 16-1411 Applied: 5/20/2016 Issued: 8/28/2017 Finaled: Type: Residential Accessory Structures Permit Work: DETACHED HORSE BARN NO ELECTRIC OR PLUMBING Sub Type: Barns, Sheds, & Greenhouses Address: 290 KITTS WAY Class: Status: Issued City ID: Washoe # Units: 1 Value: $78,180.48 Total Fees: $1,662.49 Names: Sq Ft: 0 Parcel: 045-310-82 Balance Due: $0.00 OWNER HANSEN OTT H & KIMBERLY A RENO, NV, 89521 CONTACT HANSEN KIM RENO, NV, 89521 8/31/2017 4:28:50PM Page 1 of 167 WASHOE COUNTY Permit Activity Report (Long Version) Permit Date: Issued 8/1/2017 to 8/31/2017 Permit #: 16-2829 Applied: 9/23/2016 Issued: 8/2/2017 Finaled: Type: Commercial New, Add or Tenant Improvement Permit Work: T I FOR MARIJUANNA INFUSED PRODUCTS AREA MIP SEE 16 2230 FOR Sub Type: Add INTERIOR DEMO AND CORE SHELL PERMIT Commercial Address: 2 ERIC CIR Class: 437 Commercial Remodel, Tenant Status: Issued Imp, -

Trainers Steve Asmussen Thomas Albertrani

TRAINERS TRAINERS THOMAS ALBERTRANI Bernardini: Jockey Club Gold Cup (2006); Scott and Eric Mark Travers (2006); Jim Dandy (2006); Preakness (2006); Withers (2006) 2015 RECORD Brilliant Speed: Saranac (2011); Blue Grass 1,499 252 252 217 $10,768,759 (2011) Buffum: Bold Ruler (2012) NATIONAL/ECLIPSE CHAMPIONS Criticism: Long Island (2008-09); Sheepshead Curlin: Horse of the Year (2007-08), Top Older Bay (2009) Male (2008), Top 3-Year-Old Male (2007) Empire Dreams: Empire Classic (2015); Kodiak Kowboy: Top Male Sprinter (2009) Birthdate - March 21, 1958 Commentator (2015); NYSS Great White Way My Miss Aurelia: Top 2-Year-Old Filly (2011) Birthplace - Brooklyn, NY (2013) Rachel Alexandra: Horse of the Year (2009), Residence - Garden City, NY Flashing: Nassau County (2009) Top 3-Year-Old Filly (2009) Family - Wife Fonda, daughters Teal and Noelle Gozzip Girl: American Oaks (2009); Sands Untapable: Top 3-Year-Old Filly (2014) Point (2009) 2015 RECORD Love Cove: Ticonderoga (2008) NEW YORK TRAINING TITLES 338 36 41 52 $3,253,692 Miss Frost: Riskaverse (2014) * 2010 Aqueduct spring, 12 victories Oratory: Peter Pan (2005) NATIONAL/ECLIPSE CHAMPION Raw Silk: Sands Point (2008) CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Bernardini: Top 3-Year-Old Male (2006) Ready for Rye: Quick Call (2015); Allied Forces * Campaigned 3-Year-Old Filly Champion (2015) Untapable in 2014, which included four Grade CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Romansh: Excelsior H. (2014); Discovery H. 1 wins: the Kentucky Oaks, the Mother Goose, * Trained Bernardini, who won the Preakness, (2013); Curlin (2013) the -

2008 Selected Yearling Sale Catalog Corrections

2008 SELECTED YEARLING SALE CATALOG CORRECTIONS & UPDATES New and reduced records, earnings and stakes between August 4 and September 18, listed in hip number order. 1ST AND 2ND SEASON SIRES REPRESENTED IN THIS CATALOG By ALLAMERICAN NATIVE p,3,1:49.4. Sire of 64 in 2:00, including: NATIVE BRIDE (M) p,3,1:50.1f-’08, TODD J H HANOVER p,3,1:50.3-'08, A AND G'SCONFUSION (M) p,2,1:50.3, SAYMYNAMESAYMYNAME (M) p,3,1:51.1f-’08, AMERICAN FIREDOG p,2,1:51.2-'08, PEDI- GREE SNOB (M) p,2,1:51.4-'08, LADY ANNIE (M) p,2,1:52f, BUCKEYE NATION p,2,1:53.1f-'08. By AMIGO HALL 3,1:54. Sire of 2 in 2:00, including: MY FRIEND 2,1:58-'08, DAYLON MYSTIQUE (M) 2,1:59.4h-’08, IGUAL QUE TU (M) 2,2:01.1f-’08, JUSTWIN (M) 2,2:01.2h-’08, FRIENDLY AMIGO (M) 2,Q2:02.3-'08, LEXIS AMIGO 2,Q2:03.1-'08, SINGIN MOE (M) 2,2:04.1f-’08, TOWN HALL BABE (M) 2,2:04.2h-’08, LARISSA (M) 2,2:04.4h-’08, etc. By ART MAJOR p,4,1:48.4. Sire of 107 in 2:00, including: ART OFFICIAL p,3,1:47-'08 ($1,393,228), MAJOR IN ART p,2,1:50.4-'08, MAJOR STONE p,3,1:51.2-'08, SANTANNA BLUE CHIP p,2,1:51.3 ($1,519,725), ARTIMITTATESLIFE (M) p,3,1:52-'08, MAJOR HOTTIE p,3,1:52-'08, MADAM COUNTESS (M) p,3,1:52.1f-’08, HAY GOODLOOKING p,2,1:52.4f-'08. -

The Blind Chatelaine's Keys

THE BLIND CHATELAINE’S KEYS Her Biography Through Your Poetics Begun by Eileen R. Tabios Completed by Others BlazeVOX [books] Buffalo, New York I. THE MODEST CHATELAINE’S KEYS A SELECTION OF KEYS Poetry After The Egyptians Determined The Shape of the World is a Circle, 1996 Beyond Life Sentences, 1998 The Empty Flagpole (CD with guest artist Mei-mei Berssenbrugge), 2000 Ecstatic Mutations, 2001 (with short stories and essays) Reproductions of The Empty Flagpole, 2002 Enheduanna in the 21st Century, 2002 There, Where the Pages Would End, 2003 Menage a Trois With the 21st Century, 2004 Crucial Bliss Epilogues, 2004 The Estrus Gaze(s), 2005 POST BLING BLING, 2005 I Take Thee, English, For My Beloved, 2005 The Secret Lives of Punctuations, Vol. I, 2006 Dredging for Atlantis, 2006 It’s Curtains, 2006 SILENCES: The Autobiography of Loss, 2007 The Singer and Others: Flamenco Hay(na)ku, 2007 The Light Sang As It Left Your Eyes: Our Autobiography, 2007 Novel Novel Chatelaine, 2008-09 Short Story Collection Behind The Blue Canvas, 2004 Essay Collections Black Lightning, 1998 (poetry essays/interviews) My Romance, 2002 (art essays with poems) Editor Asian Pacific American Journal (with Eric Gamalinda), 1996-1999 The Anchored Angel: Selected Writings by Jose Garcia Villa, 1999 Bridgeable Shores: Selected Poems (1969-2001) by Luis Cabalquinto, 2001 Gravities of Center: Poems by Barbara Jane Reyes, 2002 Babaylan: An Anthology of Filipina and Filipina American Writers (with Nick Carbo), 2002 INTERLOPE #8: Innovative Writing by Filipino/a Americans, 2002 Screaming Monkeys (with Evelina M. Galang, Jordan Isip, Sunaina Maira, and Anida Yoeu Esguerra), 2004 Galatea Resurrects (A Poetry Engagement), 2006-Present 13 Images From A Waking Dream By Juaniyo Arcellana Review of Reproductions of the Empty Flagpole (Marsh Hawk Press, New York, 2002) The Philippine Star, November 25, 2002 One might be hard-pressed to review a book like Eileen R. -

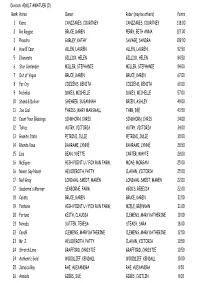

Circuit Points

Division: ADULT AMATUER (0) Rank Horse Owner Rider (may be others) Points 1 Kiera CANIZARES, COURTNEY CANIZARES, COURTNEY 318.00 2 Rio Reggae BRUCE, KAREN PERRY, BETH ANNA 117.00 3 Phaedra GURLEY, KATHY SAVAGE, SANDRA 109.00 4 How B'Czar ALLEN, LAUREN ALLEN, LAUREN 92.50 5 Illuminate GILLICK, HELEN GILLICK, HELEN 84.50 6 Star Contender MILLER, STEPHANIE MILLER, STEPHANIE 84.00 7 Out of Vogue BRUCE, KAREN BRUCE, KAREN 67.00 8 Far Cry COZZENS, BENITA COZZENS, BENITA 60.00 9 Nickolas DUKES, MICHELLE DUKES, MICHELLE 57.00 10 Stand & Deliver SHEARER, SUSANNAH BRIEN, ASHLEY 49.00 11 Joe Cool FARISS, MARY MARSHALL TABB, DEE 43.50 12 Count Your Blessings SINKHORN, CHRIS SINKHORN, CHRIS 34.00 12 Toltec AUTRY, VICTORIA AUTRY, VICTORIA 34.00 13 Granite State PETRINI, JULIE PETRINI, JULIE 30.00 14 Rhonda Vous BAHRAMI, LYNNE BAHRAMI, LYNNE 28.50 15 Isis BEAN, YVETTE CARTER, WHYTE 28.00 16 McGuyer HIGH POINT U / FOX RUN FARM, MOAG, MORGAN 25.00 16 Never Say Never HEUCKEROTH, PATTY CLAVAN, VICTORIA 25.00 17 Nell Grey LONDAHL-SMIDT, MAREN LONDAHL-SMIDT, MAREN 22.00 17 Seaborne's Mariner SEABORNE, FARM AGOCS, REBECCA 22.00 18 Calista BRUCE, KAREN BRUCE, KAREN 21.50 19 Fontaine HIGH POINT U / FOX RUN FARM, MIELE, BRENNAN 21.00 20 Fortuna KEITH, CLAUDIA CLEMENS, MARY KATHERINE 19.00 21 Nevada SUTTER, TERESA STEADY, SARA 18.00 22 Cavalli CLEMENS, MARY KATHERINE CLEMENS, MARY KATHERINE 12.50 23 Mr. Z HEUCKEROTH, PATTY CLAVAN, VICTORIA 10.50 24 Stretch Limo GRAFFORD, CHRISTIE GRAFFORD, CHRISTIE 10.50 24 Authentic Gold WOODLIEF, KENDALL WOODLIEF, KENDALL 10.00 -

Caroline Clement the Hidden Life of Mazo De La Roche’S Collaborator

Can Lit 184 proof 3 EDITED 5/11/05 2:21 PM Page 46 Heather Kirk Caroline Clement The Hidden Life of Mazo de la Roche’s Collaborator “In privacy I can find myself and the creative impulse in me can move unhampered,” said Mazo de la Roche in a interview. Finding the truth about the author of the phenomenally successful Jalna novels has been difficult, for she herself was reticent and evasive. Even the best biographer of de la Roche, Ronald Hambleton, made mistakes: for example, he missed the Acton years. Joan Givner uncovered the Acton years, but one aspect of her Mazo de la Roche: The Hidden Life was terribly wrong: de la Roche was not a child molester who victimized her cousin and life-long companion Caroline Clement.1 De la Roche herself had said in her autobi- ography, Ringing the Changes, that she and Clement were “raised together as sisters,” but Givner, guessing at Clement’s age, contradicted this statement saying “Caroline was much more likely to have found in Mazo a surrogate parent than a playmate her own age”(). De la Roche had said that the two women first met and began engaging in their innocent “play” when de la Roche was seven years old and Clement was about the same age (–, –). Givner, however, insisted that “Caroline was probably a child of seven and Mazo a young woman in her mid-teens” when the two women came together. Furthermore, Givner pronounced, the play was “erotic” (–). Givner implied that Clement was hiding de la Roche’s crime when she became a “willing collaborator” in giving incorrect dates of birth for the two of them. -

Download Putnam's Word Book

Putnam's Word Book by Louis A. Flemming Putnam's Word Book by Louis A. Flemming Produced by the Distributed Proofreaders. Putnam's Word Book A Practical Aid in Expressing Ideas through the Use of an Exact and Varied Vocabulary By Louis A. Flemming Copyright, 1913 by G. P. Putnam's Sons (Under the title _Synonyms, Antonyms, and Associated Words_) Preface page 1 / 1.424 The purpose of this book, as conceived by the author, is not to attempt to create or to influence usage by pointing out which words should or should not be used, nor to explain the meaning of terms, but simply to provide in a form convenient for reference and study the words that can be used, leaving it to those who consult its pages to determine for themselves, with the aid of a dictionary if necessary, which words supply the information they are looking for or express most accurately the thoughts in their minds. The questions, therefore, that were constantly in the author's mind while he was preparing the manuscript were not, _is_ this word used? nor _should_ it be used? but is it a word that some one may want to know as a matter of information or to use in giving expression to some thought? When the word in question seemed to be one that would be of service it was given a place in the collection to which it belongs. Believing the book would be consulted by students and workers in special fields, the author incorporated into it many words, including some technical terms, that might, in the case of a work of more restricted usefulness, have been omitted. -

The Paid Publishing Guidebook 1143 Magazines, Websites, & Blogs That Pay Freelance Writers

Freedom With Writing Freedom With Writing Presents The Paid Publishing Guidebook 1143 Magazines, Websites, & Blogs that Pay Freelance Writers Updated March, 2019 2019 Edition Copyright 2019 Freedom With Writing. All rights reserved. Do not distribute without explicit permission. To share this book, send your friends to http://www.freedomwithwriting.com/writi ng-markets/ Questions, complaints, corrections, concerns? Email [email protected] Suggestions for additional markets? Email [email protected] Edited By Jacob Jans Contributions by Fatima Saif, S. Kalekar, Tatiana Claudy, and the contributors to Freedom With Writing. Table of Contents Table of Contents.......................................................................................... 4 Introduction.................................................................................................. 6 How to Write a Pitch that Gets You Published...............................................8 Case Study: How I Got Paid to Write for Vice as a Teenager........................ 12 Frequently Asked Questions........................................................................15 1143 Magazines, Websites & Blogs That Pay Freelance Writers...............19 Lifestyle / Entertainment.............................................................................20 General Interest / News.............................................................................. 28 Finance / Business.......................................................................................37 -

TURF E FOMENTO 3

TURF e FOMENTO 3. PAU LO NA CAPA: ARTUR° A. vencedor do Derby Sul Americano de 1961 TURF e FOMENTO FEVEREIRO DE 1961 (publicação mensal do JOCKEY CLUB DE SÃO PAULO) Já se encontram em viagem da Inglaterra para o porto de Santos as dezenove éguas de cria que a Diretoria do Jockey Club de São Paulo encarregou o criador Dr. Jorge da Cunha Buenos d.e comprar aos leilões de Newmarket, em fins ele 1960. Problemas de transporte surgiram com a existência de fortes tempestades no Mar do Norte, dando em lugar uma maior cautéla no embarque das referidas repro. dutoros para o Brasil, só agora tornado possível. Algum tempo depois da Chegada do lóte ao Pôsto de Monta do Jockey Club de São Paulo, serão marcadas as datas dos leilões, os quais obedecerão a um Regulamento, ora sendo preparado pelo De- partamento de Fomento, com o mesmo espirito de cooperação com nossos criadores de puro sangue de corridas que tem caracterisado outras trausações do mesmo genero. No presente número de TURF E FOMENTO, estamos publicando as linhagens das dezenove 'éguas importadas, até á quinta geração, para melhor estudo dos interessados na aquisição. .4 Em ocasião oportuna, a Diretoria mandará publicar um Catalogo repleto de detalhes, não só sobre os animais em questão, como também sobre os seus ancestrais, para ampla elucidação dos provareis compradores, SUGESTÕES EM TORNO DE UM SÉRIO PROBLEMA Um dos problemas que mais impres- focalizada a origem do problema agora s.ionaram os criadores de S. Paulo, neste defrontado pela criação paulista. ano de 1960-1961, foi o do grande nú- Essa nossa observação se prendeu ao mero de reprodutoras indicadas como fato de termos visto diversos potros cuja "vazias", apesar dos repetidos serviços. -

Bluemoon Product List

Perennial Nursery Specializing in unusual perennials & sustainable plants native plants • ornamental grasses • hostas • daylillies QDWLYHSODQWVRUQDPHQWDOJUDVVHVKRVWDVGD\OLOOLHVDavid Austin roses and much more Offering a wide'DYLG$XVWLQURVHVDQGPXFKPRUH variety of pot sizes - from 2qt. to 5gal. Garden2IIHULQJDZLGHYDULHW\RISRWVL]HVIURPTWWRJDO Design, Installation and Maintenance also available *DUGHQ'HVLJQ,QVWDOODWLRQDQG0DLQWHQDQFHDOVRDYDLODEOH Blue Moon Farm Nursery • 173 Saugatucket Road - Wakefield, RI 02879 %OXH0RRQ)DUP1XUVHU\6DXJDWXFNHW5RDG:DNHÀHOG5,Cell: 401-258-1783 • Phone and Fax: 401-284-2369 Email:&HOO3KRQHDQG)D[ [email protected] • Jane Case - Proprietor (PDLOEOXHPRRQIDUP#FR[QHW-DQH&DVH3URSULHWRUwww.bluemoonfarmperennials.com ZZZEOXHPRRQIDUPSHUHQQLDOVFRP N/P 2009 ! """# $%! &""" ' ' ( ) * +,!- . / ,%!00 &+$!- +1!- , +,! - +1! 2(' 3 4 ' 4( '4 2 / 3 ' 3 ! 3 ' ' '!. ' 3 3! 56 7 ' ( ( ! ( ' ( ! ( ( ) 2 % 2& 89 4 36 2 %8942& 89 : 2 %89: 2& ; 2 %;2& 4 ; : 3%4;: & !, 8 <8 /: </8 9 ! Roses Ornamental Grass David Austin Roses N Acorus - Sweet Flag 5 gal $ 36.00 calamus ‘Variegatus’ $ 12.00 7 gal $ 46.00 calamus ‘Variegatus’ 2 gal $ 17.00 Abraham Darby gramineus ‘Golden Pheasant’ $ 12.00 Altissimo N Andropogon - Big Bluestem Ambridge Rose gerardii $ 12.00 A Shropshire Lad glomeratus $ 12.00 Brother Cadfael virginicus $ 12.00 Carding Mill Calamagrostis - Feather Reed Grass Comtes de Champagne acutiflora ‘Avalanche’ $ 12.00 Crocus Rose acu. ‘Karl