Lights, Camera, Action-Bringing Books To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Books Added to the Collection: July 2014

Books Added to the Collection: July 2014 - August 2016 *To search for items, please press Ctrl + F and enter the title in the search box at the top right hand corner or at the bottom of the screen. LEGEND : BK - Book; AL - Adult Library; YPL - Children Library; AV - Audiobooks; FIC - Fiction; ANF - Adult Non-Fiction; Bio - Biography/Autobiography; ER - Early Reader; CFIC - Picture Books; CC - Chapter Books; TOD - Toddlers; COO - Cookbook; JFIC - Junior Fiction; JNF - Junior Non Fiction; POE -Children's Poetry; TRA - Travel Guide Type Location Collection Call No Title AV AL ANF CD 153.3 GIL Big magic : Creative living / Elizabeth Gilbert. AV AL ANF CD 153.3 GRA Originals : How non-conformists move the world / Adam Grant. Irrationally yours : On missing socks, pick up lines, and other existential puzzles / Dan AV AL ANF CD 153.4 ARI Ariely. Think like a freak : The authors of Freakonomics offer to retrain your brain /Steven D. AV AL ANF CD 153.43 LEV Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner. AV AL ANF CD 153.8 DWE Mindset : The new psychology of success / Carol S. Dweck. The geography of genius : A search for the world's most creative places, from Ancient AV AL ANF CD 153.98 WEI Athens to Silicon Valley / Eric Weiner. AV AL ANF CD 158 BRO Rising strong / Brene Brown. AV AL ANF CD 158 DUH Smarter faster better : The secrets of prodctivity in life and business / Charles Duhigg. AV AL ANF CD 158.1 URY Getting to yes with yourself and other worthy opponents / William Ury. 10% happier : How I tamed the voice in my head, reduced stress without losing my edge, AV AL ANF CD 158.12 HAR and found self-help that actually works - a true story / Dan Harris. -

The Kindergarten Canon: 100 Books Every Child Should Encounter By

The Kindergarten Canon Title Author 1 is One Tasha Tudor Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day Judith Viorst & Ray Cruz Amazing Grace Mary Hoffman & Caroline Binch Anansi the Spider Gerald McDermott* Are You My Mother? P.D. Eastman Bear Called Paddington, A Michael Bond Bear Snores On Karma Wilson & Jane Chapman Beauty and the Beast, The Brothers Grimm* Big Red Barn, The Margaret Wise Brown & Felicia Bond Birthday for Frances, A Russell Hoban & Garth Williams Blueberries for Sal Robert McCloskey Bremen Town Musicians, The Brothers Grimm* Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? Bill Martin Jr. & Eric Carle Caps for Sale Esphyr Slobodkina Carrot Seed, The Ruth Krauss & Crockett Johnson Cars and Trucks and Things that Go Richard Scarry Cat in the Hat, The Dr. Seuss Chair for My Mother, A Vera B. Williams Bill Martin Jr. (author), John Archambault Chicka Chicka Boom Boom (author), and Lois Ehlert Chrysanthemum Kevin Henkes Cinderella Brothers Grimm* Click, Clack, Moo: Cows that Type Doreen Cronin & Betsy Lewin Corduroy Don Freeman Curious George Margret Rey and H. A. Rey Dear Zoo Rod Campbell Emperor's New Clothes, The Hans Christian Andersen* Fisherman and his Wife, The Brothers Grimm* Frederick Leo Lionni Freight Train Donald Crews Frog and Toad are Friends Arnold Lobel George and Martha James Marshall Gingerbread Man , The Fairy Tale* Giving Tree, The Shel Silverstein Go, Dog. Go! P.D. Eastman Goggles Ezra Jack Keats Goldilocks and the Three Bears Brothers Grimm* Good Night Gorilla Peggy Rathmann Good Night Moon Margaret Wise Brown & Clement Hurd Green Eggs and Ham Dr. -

Big Books Available to Borrow from the Prendergast Library

Big Books Animals Should Definitely Not Wear Clothing - Judi Barrett Big Red Barn - Margaret Wise Brown Caps for Sale - Esphyr Slobodkin Caps, Hats, Socks, and Mittens - Louise Borden Chicken Soup With Rice - Maurice Sendak A Clean House for Mole and Mouse - Harriet Ziefert Clifford’s Birthday Party - Norman Bridwell Corduroy - Don Freeman Curious George - H. A. Rey Dinosaurs, Dinosaurs - Byron Barton Don’t Forget the Bacon – Pat Hutchins The Doorbell Rang - Pat Hutchins Eeny, Meeny, Miney Mouse – Gwen Pascoe The Farmer in the Dell – traditional story, illustrated by Mary Maki Rae Feathers for Lunch - Lois Ehlert Flashing Fire Engines – Tony Mitton Flower Garden - Eve Bunting Franklin in the Dark - Paulette Bourgeois Freight Train – Donald Crews Froggy Gets Dressed - Jonathan London Goodnight Moon - Margaret Wise Brown Good Night, Owl - Pat Hutchins The Great Kapok Tree - Lynne Cherry The Greedy Goat - retold by Faye Bolton Growing Vegetable Soup – lois Ehlert Hattie and the Fox - Mem Fox Have You Seen My Duckling? – Nancy Tafuri I am a Music Man – ill. by Debra Potter I Wish I Could Fly - Ron Maris If You Give a Mouse a Cookie - Laura Numeroff If You Give a Pig a Pancake – Laura Numeroff In My Garden – Ermanno Cristini & Luigi Puricelli Inside a Barn in the Country – Alyssa Capucili Interruptions – Bronwen Scarffe & Diane Snowball Is Your Mama a Llama? - Deborah Guarino Jamberry - Bruce Degen Jump, Frog, Jump - Robert Kalan King Bidgood’s in the Bathtub - Audrey Wood Little Blue Ben – Phoebe Gilman Little Cloud – Eric Carle The Little -

The Kindergarten Canon: the 100 Best Children’S Books by Michael J

The Kindergarten Canon: The 100 Best Children’s Books By Michael J. Petrilli 1. “1 is One” By Tasha Tudor 2. “Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day” By Judith Viorst & Ray Crus 3. “Anansi the Spider” By Gerald McDermott 4. “Amazing Grace” By Mary Hoffman & Caroline Binch 5. “Are You My Mother?” By P.D. Eastman 6. “A Bear Called Paddington” By Michael Bond 7. “Bear Snores On” By Karma Wilson & Jane Chapman 8. “The Beauty and the Beast” By Brothers Grimm 9. “Big Red Barn” By Margaret Wise Brown 10. “A Birthday for Frances” By Russell Hoban & Lillian Hoban 11. “Blueberries for Sal” By Robert McCloskey 12. “The Bremen Town Musicians” By Brothers Grimm 13. “Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?” By Bill Martin & Eric Carle 14. “Caps for Sale” By Esphyr Slobodkina 15. “The Carrot Seed” By Ruth Krauss & Crockett Johnson 16. “Cars and Trucks and Things that Go” By Richard Scarry 17. “The Cat and the Hat” By Dr. Seuss 18. “A Chair for My Mother” By Vera B. Williams 19. “Chicka Chicka Boom Boom” By Bill Martin, Jr. & John Archambault 20. “ Cinderella” Brothers Grimm 21. “Click, Clack, Moo: Cows that Type” By Doreen Cronin & Betsy Lewin 22. “Corduroy” By Don Freeman 23. “Curious George” By Margret Rey & H.A. Rey 24. “Dear Zoo” By Rod Campbell 25. “The Emperor’s New Clothes” By Hans Christian Andersen 26. “The Fisherman and His Wife” By Brothers Grimm 27. “Frederick” By Leo Lionni 28. “Freight Train” By Donald Crews 29. “Frog and Toad are Friends” By Arnold Lobell 30. -

Reading Counts

Title Author Reading Level Sorted Alphabetically by Title 13 James Howe 4 47 Walter Mosley 5.2 1632 Eric Flint 8.1 1776 David McCullough 12.5 1984 George Orwell 8.2 2095 Jon Scieszka 5.4 29-Jun-99 David Wiesner 5.3 11-Sep-01 Andrew Santella 5.5 "A" Is for Abigail Lynne Cheney 4.6 $1.00 Word Riddle Book, The Marilyn Burns 6.5 1,2,3 In The Box Ellen Tarlow 1.2 10 Best Things… Dad Christine Loomis 1.6 10 Fat Turkeys Tony Johnston 1.7 10 For Dinner Jo Ellen Bogart 2.4 10 Minutes Till Bedtime Peggy Rathmann 1.5 10,000 Days Of Thunder Philip Caputo 7.6 100 Days Of School Trudy Harris 2.2 100 Inventions That Shaped... Bill Yenne 10 100 Selected Poems E.E. Cummings 7.2 100 Years In Photographs George Sullivan 6.8 1000 Facts About Space Pam Beasant 4.9 1000 Facts About The Earth Moira Butterfield 4.2 1000 Questions And Answers Richard Tames 5.6 1001 Animals to Spot Ruth Brocklehurst 1.6 1001 Things to Spot in the Sea Katie Daynes 2.3 100-Pound Problem, The Jennifer Dussling 2.4 100th Day Of School (Bader) Bonnie Bader 2.1 100th Day Of School, The Angela Shelf Medearis 1.5 100th Day Worries Margery Cuyler 2.1 100th Day, The Grace Maccarone 1.8 100th Thing About Caroline Lois Lowry 5.5 101 Dalmatians, The Dodie Smith 6.1 101 Hopelessly Hilarious Jokes Lisa Eisenberg 3.1 101 Tips For - A Best Friend Nancy Krulik 4.5 101 Ways To Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw 4.8 101 Ways To Bug Your Teacher Lee Wardlaw 4.2 10-Step Guide...Monster Laura Numeroff 1.5 12 Again Sue Corbett 5.7 13 Ghosts: Strange But True.. -

Eating, Reading and 'Rithmetic

EATING, READING AND ’RITHMETIC Choosing Books About Food for Kids American Heart Association Kids’ Corn is Maize: The Gift of the Indians Growing Vegtable Soup Cookbook edited by Mary Winston by Aliki (HarperTrophy, 1986) by Lois Ehlert (Harcourt, 1990) (Times Books, 1993) A Cow, a Bee, a Cookie, and Me The Ghost’s Dinner The Apple Pie Tree by Zoe Hall, by Meredith Hooper, illustrated by by Jacques Duquennoy illustrated by Shari Halpern Alison Bartlett (Kingfisher, 1997) (Golden Books, 1996) (Blue Sky/Scholastic, 1996) The Doorbell Rang “Hi, Pizza Man!” The Beastly Feast by Bruce Goldstone, by Pat Hutchins (Greenwillow, 1986) by Virginia Walter, illustrated by illustrated by Blair Lent (Holt, 1998) Ponder Goembel (Orchard, 1995) Eat Up Gemma by Sarah Hayes, Benny Bakes a Cake illustrated by Jan Ormerod How Pizza Came to Queens by Eve Rice (Greenwillow, 1993) (Lothrop, Lee & Shepard, 1988) by Dayal KaurKhalsa (Crown, 1989) The Berenstain Bears and Too Much Junk Everybody Cooks Rice How to Make an Apple Pie and See the Food by Stan and Jan Berenstain by Norah Dooley, illustrated by World by Marjorie Priceman and (RandomHouse, 1985) Peter J. Thornton (Carolrhoda, 1991) T. Gates (Dragonfly, 1996) Bread and Jam for Francis Everyone Likes to Eat: How Children Can I Don’t Like Peas by Russell Hoban, illustrated by Eat Most of the Food They Enjoy and Still by Marie Vinje (SchoolZone, 1993) Lillian Hoban (HarperTrophy, 1986) Take Care of Their Diabetes by Hugo Hollerorth and If You Give a Moose a Muffin The Bread that Grew Debra Kaplan (Chronimed, 1993) by Laura Numeroff, illustrated by by Roberta L. -

Children Book Illustrators: the Inside Look Into Their Life, and Their Books

YOUTH November 2019 Children Book Illustrators: The inside look into their life, and their books Felecia Bond Anna Dewdney Dr. Seuss 1 TABLE OF 12 Silly CONTENTS Seuss 20 Felecia Bond 4 Anna Dewdney 2 3 YOUTH Magazine November 2019 WHO IS SHE? Felicia Bond, illustrator, was born to American parents in Yokohama, Japan, where she lived for two years. Bond grew up in Bronxville, New York and Houston, Texas with her four Playful brothers and two sisters. She is the second child in a family of seven. It was Felecia while living in New York that she observed a beam of light coming in her bedroom window at age five and knew that art was her calling. Bond cites numerous inspirations as a child, among them the covers of The New Yorker, the drawings in her Girl Scout Handbook, the sketches her mother drew for her and her siblings, and the since its publication and If You Give a addition to the If You Give A . series, BondBy Jane Smith art in children’s books. Bond was Mouse a Cookie has sold over a million she has also illustrated, among other especially drawn to the painterly, copies. At age twenty-two is when she titles, Big Red Barn by Margaret Wise expressive style of Ludwig Bemelmans moved to New York City with nine Brown and Little Porcupine’s Christmas in his Madeline books and the hundred dollars and worked several by Joseph Slate. She’s the author and sensitive ink drawings by Garth jobs, including illustrating botanical illustrator of the Poinsettia books, The Williams in Charlotte’s Web and books, working as a freelance scene Day It Rained Hearts, The Halloween Stuart Little. -

Book Reading Point Title Author Level Value

Book Reading Point Title Author Level Value Ice Is...Whee! Carol Greene 0.3 0.5 The Ball Game David Packard 0.4 0.5 The Day I Had to Pla Crosby Bonsall 0.5 0.5 Down on the Farm Rita Lascaro 0.5 0.5 Mine's the Best Crosby Bonsall 0.5 0.5 Grandma's Cat Helen Ketteman 0.6 0.5 I Hate My Bow Hans Wilhelm 0.6 0.5 My Dog's the Best! Stephanie Calmenso 0.6 0.5 The Tapping Tale Judy Giglio 0.6 0.5 Cloudy Day Sunny Day Donald Crews 0.7 0.5 The Ear Book Al Perkins 0.7 0.5 I Shop with My Daddy Grace Maccarone 0.7 0.5 Itchy, Itchy Chicken Grace Maccarone 0.7 0.5 Kites Bettina Ling 0.7 0.5 Rabbit and Turtle Go Lucy Floyd 0.7 0.5 Raindrops Sandy Gay 0.7 0.5 Andy That's My Name Tomie De Paola 0.8 0.5 The Eye Book Dr. Seuss 0.8 0.5 Hide and Seek Brown/Carey 0.8 0.5 Who Stole the Cookie Judith Moffatt 0.8 0.5 David Goes to School David Shannon 0.9 0.5 Don't Let the Pigeon Mo Willems 0.9 0.5 How Far Will I Fly? Sachi Oyama 0.9 0.5 I'm a Caterpillar Jean Marzolla 0.9 0.5 Look! I Can Read! Susan Hood 0.9 0.5 Rip's Secret Spot Kristi T. Butler 0.9 0.5 Shoveling Snow (Wigg Pat Cummings 0.9 0.5 Splash! Ann Jonas 0.9 0.5 Two Bear Cubs Ann Jonas 0.9 0.5 Why the Frog Has Big Betsy Franco 0.9 0.5 Animal Babies Bobbie Hamsa 1 0.5 Are You My Mother? P.D. -

Accelerated Reader Test List Report

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5550EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Verna Aardema 4.0 0.5 5490EN Song and Dance Man Karen Ackerman 4.0 0.5 8303EN George Washington Carver Gene Adair 9.8 4.0 34553EN Cam Jansen and the Barking Treas David A. Adler 3.5 1.0 17659EN Cam Jansen and the Chocolate Fud David A. Adler 3.7 1.0 14660EN Cam Jansen and the Ghostly Myste David A. Adler 3.4 1.0 17663EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery at th David A. Adler 3.5 1.0 5210EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery at th David A. Adler 3.7 1.0 18707EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of Fl David A. Adler 3.4 1.0 17660EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of th David A. Adler 3.8 1.0 17661EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of th David A. Adler 3.7 1.0 7605EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of th David A. Adler 3.9 1.0 7606EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of th David A. Adler 3.8 1.0 17662EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of th David A. Adler 3.7 1.0 17664EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of th David A. Adler 3.9 1.0 17665EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of th David A. Adler 3.8 1.0 308EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of th David A. Adler 3.2 1.0 18708EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of th David A. -

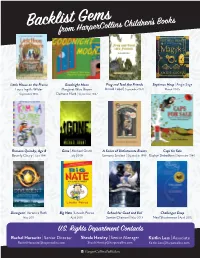

Backlist Gems

Backlistfrom Gems HarperCollins Children’s Books Little House on the Prairie Goodnight Moon Frog and Toad Are Friends Septimus Heap | Angie Sage Laura Ingalls Wilder Margaret Wise Brown Arnold Lobel | September 1970 March 2005 September 1935 Clement Hurd | September 1947 Ramona Quimby, Age 8 Gone | Michael Grant A Series of Unfortunate Events Caps for Sale Beverly Cleary | June 1981 July 2008 Lemony Snicket | September 1999 Esphyr Slobodkina | September 1940 Divergent | Veronica Roth Big Nate | Lincoln Peirce School for Good and Evil Challenger Deep May 2011 April 2010 Soman Chainani | May 2013 Neal Shusterman | April 2015 U.S. Rights Department Contacts Rachel Horowitz | Senior Director Sheala Howley | Senior Manager Kaitlin Loss | Associate [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] MIDDLE GRADE, AGES 8-12 CAPTIVATING FANTASY SERIES York | Laura Ruby Max Tilt | Pete Lerangis Wing & Claw | Linda Sue Park The Peculiar | Stefan Bachmann May 2017 October 2017 March 2016 September 2012 The Menagerie The Secret Zoo | Bryan Chick The Magnificent 12 Lock and Key | Ridley Pearson Tui T. Sutherland and June 2010 Michael Grant | August 2010 September 2016 Kari Sutherland | March 2013 The Incorrigible Children of The Thickety | J. A. White The Hero’s Guide to Saving Ashton Place | Maryrose Wood May 2012 Your Kingdom March 2010 Christopher Healy | May 2012 MIDDLE GRADE, AGES 8-12 HEARTFELT FAMILY STORIES Contemporary Romance The Year of Billy Miller | Kevin Henkes Olive’s Ocean | Kevin Henkes Blackbird Fly | Erin Entrada Kelly September 2013 August 2003 March 2015 Fantasy and The Land of Forgotten Girls Echo’s Sister | Paul Mosier Train I Ride | Paul Mosier Mystery Erin Entrada Kelly | March 2016 August 2018 January 2017 One Crazy Summer | Rita Williams-Garcia All Rise for the Honorable Perry T. -

TITLE AUTHOR Book Level POINTS 10 Little Rubber Ducks Eric Carle 2.4 0.5 100 School Days Anne Rockwell 2.8 0.5 the 100Th Day Of

TITLE AUTHOR Book Level POINTS 10 Little Rubber Ducks Eric Carle 2.4 0.5 100 School Days Anne Rockwell 2.8 0.5 The 100th Day of School Angela Shelf Medearis 1.4 0.5 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw 3.9 5 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola 4.4 1 3 Little Firefighters Stuart J. Murphy 1.7 0.5 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins Dr. Seuss 4 1 97 Ways to Train a Dragon Kate McMullan 3.3 2 The A.D.D. Book for Kids Rotner/Kelly 2.2 0.5 Abby Takes a Stand Pat McKissack 3.6 1 Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner 2.6 0.5 Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6 Abigail the Breeze Fairy Daisy Meadows 4.1 1 Abiyoyo Pete Seeger 2.2 0.5 The Abominable Snowman Doesn't Roast Marshmallows Debbie Dadey 4 1 About Mammals: A Guide for Children Cathryn Sill 2.1 0.5 Abraham Lincoln (United States Presidents) Anne Welsbacher 5 0.5 The Absent Author Ron Roy 3.4 1 Absolutely Lucy Ilene Cooper 2.7 1 Abuela Arthur Dorros 2.5 0.5 ack as in Snack Pam Scheunemann 1.6 0.5 Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt 6.6 10 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon Trail Diary... Kristiana Gregory 5.5 4 Actual Size Steve Jenkins 2.8 0.5 ad as in Dad Mary Elizabeth Salzmann 1.6 0.5 Addie in Charge Laurie Lawlor 4.1 0.5 Addy's Surprise Connie Porter 4.4 1 Addy Saves the Day Connie Porter 4 1 The Adventures of Captain Underpants Dav Pilkey 4.3 1 The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Mark Twain 6.6 18 The Adventures of Super Diaper Baby Dav Pilkey 2.5 0.5 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer Mark Twain 8.1 12 Africa (Continents) Leila Merrell Foster 3.6 0.5 After the Goat Man Betsy Byars 4.5 3 After the Storm Lauren Brooke 4.3 5 Afternoon of the Elves Janet Taylor Lisle 5 4 Afternoon on the Amazon Mary Pope Osborne 2.6 1 ag as in Flag Mary Elizabeth Salzmann 1.8 0.5 Aggie and Will Larry Dane Brimner 1.2 0.5 ain as in Train Carey Molter 1.3 0.5 Air Is All Around You Franklyn M. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. NCTE Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 362 878 CS 214 064 AUTHOR Jensen, Julie M., Ed.; Roser, Nancy L,, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Tenth Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0079-1; ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 93 NOTE 682p.; For the previous edition, see ED 311 453. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 00791-0015; $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) -- Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF04/PC28 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Mathematical Concepts; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Material Selection; *Recreational Reading; Scientific Concepts; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Eastorical Fiction; Trade Books ABSTRACT Designed to help teachers, librarians, arid parents introduce books of exceptional literary and artistic merit, accuracy, and appeal to preschool through sixth grade children, this annotated bibliography presents nearly 1,800 annotations of approximately 2,000 books (2 or more books in a series appear in a single review) published between 1988 and 1992. Annotations are grouped under 13 headings: Biography; Books for Young Children; Celebrations; Classics; Contemporary Realistic Fiction; Fantasy; Fine Arts; Historical Fiction; Language and Reading; Poetry; Sciences and Mathematics, Social Studies; and Traditional Literature. In addition to the author and title, each annotation lists illustrators where applicable and the recommended age range of potential readers. A selected list of literary awards given to children's books published between 1988 and 1992; a description of popular booklists; author, illustrator, subject, and title indexes; and a directory of publishers are attached.