No. 798 Regional Income Inequality in Egypt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Corvus, the Roman Boarding Device

Wright State University CORE Scholar Classics Ancient Science Fair Religion, Philosophy, and Classics Spring 2020 The Corvus, the Roman Boarding Device Jacob Stickel Wright State University - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ancient_science_fair Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Military History Commons Repository Citation Stickel , J. (2020). The Corvus, the Roman Boarding Device. Dayton, Ohio. This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion, Philosophy, and Classics at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Ancient Science Fair by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A philological examination of Eratosthenes’ calculation of Earth’s circumference Kelly Staver1 1 Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio, U.S.A. Introduction Errors in Eratosthenes ’ Assumptions Historical Inconsistencies of Eratosthenes’ Final Result • A Greek mathematician named Eratosthenes calculated an accurate measurement Two of Eratosthene’s five assumtpions are either mistaken or questionable at • Cleomedes and John Philophus state Eratosthenes’ result was 250,000, whereas of the Earth’s circumference, that being 250,000 stades or close to Earth’s actual best: many others such as Vitruvius, Martianus Capella, Strabo, and many others state circumference of 40,120 km,¹ in Hellenistic Alexandria, Egypt circa 240 B.C.E.² • Assumption (1) is incorrect. The longitudinal difference between it was 252,000 stades.¹⁴ • To do this, Eratosthenes’ utilized the distance between Alexandria and Syene and Syene and Alexandria is about 3 degrees.⁶ • Benefits of 252,000 stades: gnomon measurements taken in Syene and Alexandria at noon on the summer • Assumption (2) is questionable since we do not know how long a • Yields a clean 700 stades per circular degree.¹⁵ solstice.³ stadion is. -

Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future

Economy Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi With the Egyptian children around him, when he gave go ahead to implement the East Port Said project On November 27, 2015, President Ab- Egyptians’ will to successfully address del-Fattah el-Sissi inaugurated the initial the challenges of careful planning and phase of the East Port Said project. This speedy implementation of massive in- was part of a strategy initiated by the vestment projects, in spite of the state of digging of the New Suez Canal (NSC), instability and turmoil imposed on the already completed within one year on Middle East and North Africa and the August 6, 2015. This was followed by unrelenting attempts by certain interna- steps to dig out a 9-km-long branch tional and regional powers to destabilize channel East of Port-Said from among Egypt. dozens of projects for the development In a suggestive gesture by President el of the Suez Canal zone. -Sissi, as he was giving a go-ahead to This project is the main pillar of in- launch the new phase of the East Port vestment, on which Egypt pins hopes to Said project, he insisted to have around yield returns to address public budget him on the podium a galaxy of Egypt’s deficit, reduce unemployment and in- children, including siblings of martyrs, crease growth rate. This would positively signifying Egypt’s recognition of the role reflect on the improvement of the stan- of young generations in building its fu- dard of living for various social groups in ture. -

A Study of Some Egyptian Carbonate Rocks for the Building Construction Industry ⇑ Mahrous A.M

International Journal of Mining Science and Technology 24 (2014) 467–470 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Mining Science and Technology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijmst A study of some Egyptian carbonate rocks for the building construction industry ⇑ Mahrous A.M. Ali a, , Hyung-Sik Yang b a Mining and Petroleum Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Alazhar University, Qena Branch 83513, Egypt b Energy and Resources Engineering Department, College of Engineering, Chonnam National University, Gwang-ju 500-757, South Korea article info abstract Article history: A number of geotechnical analyses were carried out on selected carbonate rock samples from eight sites Received 5 September 2013 located in Egypt. This analysis was to assess the suitability of these rocks for building construction aggre- Received in revised form 10 November 2013 gate. The analyses included properties of uniaxial compressive strength, tensile strength, porosity, water Accepted 15 February 2014 absorption, and dynamic fragmentation. The success of building construction depends to a large extent Available online 5 June 2014 on the availability of raw materials at affordable prices. Raw materials commonly used in the building industry include sands, gravels, clays and clay-derived products. Despite the widespread occurrence of Keywords: carbonate rocks throughout Egypt, the low premium placed on their direct application in the building Carbonate rocks sector may be explained in two ways: firstly, the lack of awareness of the potential uses of carbonate Building construction Raw materials rocks in the building construction industry (beyond the production of asbestos, ceiling boards, roof sheets Aggregates and Portland cement); and secondly, the aesthetic application of carbonate rocks in the building con- struction depends mainly on their physical attributes, a knowledge of which is generally restricted to within the confines of research laboratories and industries. -

Mining of Leaf Rust Resistance Genes Content in Egyptian Bread Wheat Collection

plants Article Mining of Leaf Rust Resistance Genes Content in Egyptian Bread Wheat Collection Mohamed A. M. Atia 1,* , Eman A. El-Khateeb 2, Reem M. Abd El-Maksoud 3 , Mohamed A. Abou-Zeid 4 , Arwa Salah 1 and Amal M. E. Abdel-Hamid 5 1 Molecular Genetics and Genome Mapping Laboratory, Genome Mapping Department, Agricultural Genetic Engineering Research Institute (AGERI), Agricultural Research Center (ARC), Giza 12619, Egypt; [email protected] 2 Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Tanta University, Tanta 31527, Egypt; [email protected] 3 Department of Nucleic Acid & Protein Structure, Agricultural Genetic Engineering Research Institute (AGERI), Agricultural Research Center (ARC), Giza 12619, Egypt; [email protected] 4 Wheat Disease Research Department, Plant Pathology Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center (ARC), Giza 12619, Egypt; [email protected] 5 Department of Biological and Geological Sciences, Faculty of Education, Ain Shams University, Roxy, Cairo 11341, Egypt; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +20-1000164922 Abstract: Wheat is a major nutritional cereal crop that has economic and strategic value worldwide. The sustainability of this extraordinary crop is facing critical challenges globally, particularly leaf rust disease, which causes endless problems for wheat farmers and countries and negatively affects humanity’s food security. Developing effective marker-assisted selection programs for leaf rust Citation: Atia, M.A.M.; El-Khateeb, resistance in wheat mainly depends on the availability of deep mining of resistance genes within the E.A.; Abd El-Maksoud, R.M.; germplasm collections. This is the first study that evaluated the leaf rust resistance of 50 Egyptian Abou-Zeid, M.A.; Salah, A.; wheat varieties at the adult plant stage for two successive seasons and identified the absence/presence Abdel-Hamid, A.M.E. -

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010 1. Please provide detailed information on Al Minya, including its location, its history and its religious background. Please focus on the Christian population of Al Minya and provide information on what Christian denominations are in Al Minya, including the Anglican Church and the United Coptic Church; the main places of Christian worship in Al Minya; and any conflict in Al Minya between Christians and the authorities. 1 Al Minya (also known as El Minya or El Menya) is known as the „Bride of Upper Egypt‟ due to its location on at the border of Upper and Lower Egypt. It is the capital city of the Minya governorate in the Nile River valley of Upper Egypt and is located about 225km south of Cairo to which it is linked by rail. The city has a television station and a university and is a centre for the manufacture of soap, perfume and sugar processing. There is also an ancient town named Menat Khufu in the area which was the ancestral home of the pharaohs of the 4th dynasty. 2 1 „Cities in Egypt‟ (undated), travelguide2egypt.com website http://www.travelguide2egypt.com/c1_cities.php – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 1. 2 „Travel & Geography: Al-Minya‟ 2010, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2 August http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/384682/al-Minya – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 2; „El Minya‟ (undated), touregypt.net website http://www.touregypt.net/elminyatop.htm – Accessed 26 July 2010 – Page 1 of 18 According to several websites, the Minya governorate is one of the most highly populated governorates of Upper Egypt. -

International Selection Panel Traveler's Guide

INTERNATIONAL SELECTION PANEL MARCH 13-15, 2019 TRAVELER’S GUIDE You are coming to EGYPT, and we are looking forward to hosting you in our country. We partnered up with Excel Travel Agency to give you special packages if you wish to travel around Egypt, or do a day tour of Cairo and Alexandria, before or after the ISP. The following packages are only suggested itineraries and are not limited to the dates and places included herein. You can tailor a trip with Excel Travel by contacting them directly (contact information on the last page). A designated contact person at the company for Endeavor guests has been already assigned to make your stay more special. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS: The Destinations • Egypt • Cairo • Journey of The Pharaohs: Luxor & Aswan • Red Sea Authentic Escape: Hurghada, Sahl Hasheesh and Sharm El Sheikh Must-See Spots in: Cairo, Alexandria, Luxor, Aswan & Sharm El Sheikh Proposed One-Day Excursions Recommended Trips • Nile Cruise • Sahl Hasheesh • Sharm El Sheikh Services in Cairo • Meet & Assist, Lounges & Visa • Airport Transfer Contact Details THE DESTINATIONS EGYPT Egypt, the incredible and diverse country, has one of a few age-old civilizations and is the home of two of the ancient wonders of the world. The Ancient Egyptian civilization developed along the Nile River more than 7000 years ago. It is recognizable for its temples, hieroglyphs, mummies, and above all, the Pyramids. Apart from visiting and seeing the ancient temples and artefacts of ancient Egypt, there is also a lot to see in each city. Each city in Egypt has its own charm and its own history, culture, activities. -

ISWM Options Report Qena Governorate

Ministry of Environment National Solid Waste Management Program PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION (LOT A) ASSIUT & QENA GOVERNORATES ISWM Options Report Qena Governorate Final version December 2017 This report is prepared within National Solid Waste Management Programme, Egypt. Funded by EU, Swiss, German Financial and Technical Cooperation with Egypt, Under Consulting Services for Waste Management Programme Implementation. Name: Review of Priority investment measures Version: Final Date: 14.12 2017 Prepared by the Consortium CDM Smith‐AHT‐KOCKS‐CES‐AAW Published by: Waste Management Regulatory Authority Ministry of Environment Cairo House Building‐ Fustat Misr El Quadima, Cairo ,Egypt Supported by: MoE ISWM Options Report Qena TABLE OF CONTENT Page 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 11 2. INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................. 14 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 14 OBJECTIVES ....................................................................................................................................... 14 3. CHARACTERISTICS OF QENA GOVERNORATE ................................................................................. 15 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS ................................................................................................................ -

Cairo-Luxor-Aswan-Ci

Cairo, Luxor & Aswan City Package 6 Days – 5 Nights Daily Arrivals Motorboating on the Nile, Aswan Limited to 12 participants Day 3: Cairo / Luxor to see the Temple of Isis and the Aswan High Early morning flight to Luxor; transfer to Dam. Optional extra night in Aswan is available; Tour Includes: your hotel. Morning tour the Valley of the please inquire. Overnight in Aswan. (B.L) • Flights within Egypt as per Itinerary Kings containing the secretive tombs of New Kingdom Pharaohs; enter the Tomb Day 5: Aswan / Cairo • Choice of Deluxe Hotel Plans c Return flight to Cairo. Balance of day at ai • Meals: Buffet Breakfast Daily, of Tutankhamen. Continue to the famed leisure, or take an optional tour to Abu , and R 3 Lunches. 1 Dinner on the Nile Colossi of Memnon Temple of Queen Hatshepsut. After lunch, visit the vast Simbel (See Page 23 for details). Overnight o, • All Transfers as indicated Karnak Temple-Complex, Avenue of the in Cairo. (B) l • Sightseeing with Egyptologist Guide uxo Sphinxes and the imposing Temple of Day 6: En Route by Exclusive IsramBeyond Services Luxor. Evening: Optional Sound & Light • All Entrance Fees to Sites as indicated Show at the Temple of Karnak ($75 per Transfer to the airport for your departure flight. R • Visa for Egypt (USA & Canadian person based on 2 participants, please (B) & Passports only) reserve at time of booking). (B.L) EXTEND YOUR STAY! a Day 4: Luxor / Edfu / Aswan Optional extra night in Aswan is swan Highlights: Depart Luxor driving to the Temple of Horus highly recommended; or extend • Panoramic “Cairo by Night” Tour & at Edfu, the best preserved of all large your tour to Sharm el-Sheikh on Dinner on the Nile Egyptian temples before continuing to the Red Sea, Alexandria, Jordan or c • Entrance to one of the Great Pyramids Aswan, Egypt’s southernmost city. -

Identification of Terrestrial Gastropods Species in Sohag Governorate, Egypt

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science 3(1): 45-48 (2018) https://doi.org/10.26832/24566632.2018.030105 This content is available online at AESA Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science Journal homepage: www.aesacademy.org e-ISSN: 2456-6632 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE Identification of terrestrial gastropods species in Sohag Governorate, Egypt Abd El-Aleem Saad Soliman Desoky Department of Plant protection (Agriculture Zoology), Faculty of Agriculture, Sohag University, EGYPT E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE HISTORY ABSTRACT Received: 15 January 2018 The study aims to identify of terrestrial gastropods species in Sohag Governorate during the Revised received: 10 February 2018 year 2016 and 2017. The present study was carried out for survey and identification for ran- Accepted: 21 February 2018 dom land snail in 11 districts, i.e. (Tema, Tahta, Gehyena, El-Maragha, Saqultah, Sohag, Akhmim, El-Monshah, Gerga, El-Balyana, and Dar El-Salam) at Sohag Governorate, Egypt. Samples were collected from 5 different locations in each district during 2016-2017 seasons. The monthly Keywords samples were taken from winter and summer crops (areas were cultivated with the field crops Egypt such as wheat, Egyptian clover, and vegetables crops. The results showed that found two spe- Eobania vermiculata cies of land snails, Monacha obstracta (Montagu) and Eobania vermiculata (Muller). It was -

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 THE MINTS FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1 Study Scope and Objectives .........................................................................................................1-1 -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

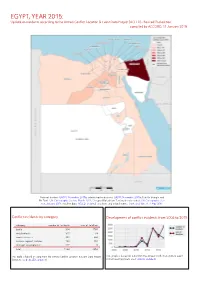

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

The Suez Canal Economic Zone: an Emerging International Commercial Hub

The Suez Canal Economic Zone: An Emerging International Commercial Hub August 2016 marks the one-year anniversary of President Abdel Fattah El Sisi’s inauguration of the Suez Canal expansion—an $8.6 billion upgrade to the nearly 140-year-old waterway to increase capacity, allow two- way maritime trafc for the frst time, reduce waiting and transit time and create new jobs and revenue. This was accompanied by the establishment of the Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCZone) – an innovative and self-sustaining industrial development corridor that will transform 461 square kilometers and six maritime ports strategically located along one of world’s most main trading routes into an international commercial hub. Through an innovative and integrated development strategy that is being implemented today, the SCZone promises to expand Egypt’s competitive economic edge by connecting 1.6 billion consumers across Europe, Asia, Africa and the Gulf and Egypt’s own growing market of 90 million people. Poised to support nearly one million new jobs and two million new residents, the SCZone will transform and modernize Egypt’s economy while creating a new center for global commerce. CUTTING EDGE COMMERCIAL CENTERS The SCZone represents a new chapter for Egypt’s economic progress. With work underway, the project is expected upon completion to create millions of new jobs while ofering Egyptian and foreign investors with top-class infrastructure, market access and streamlined administrative procedures. The regional strategy of the SCZone entails the development of lands, facilities and ports adjacent to and in the proximity of the Canal, mainly in Ain Sokhna, East Port Said, Ismailia and Qantara.