Filed a Lawsuit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BAD RIVER BAND of LAKE SUPERIOR TRIBE of CHIPPEWA INDIANS CHIEF BLACKBIRD CENTER Box 39 ● Odanah, Wisconsin 54861

BAD RIVER BAND OF LAKE SUPERIOR TRIBE OF CHIPPEWA INDIANS CHIEF BLACKBIRD CENTER Box 39 ● Odanah, Wisconsin 54861 July 11, 2020 Ben Callan, WDNR Division of External Services PO Box 7921 Madison, WI 53708-7921 [email protected] RE: Comments Concerning the Enbridge Energy, LLC Line 5 Relocation around the Bad River Reservation regarding the WDNR Wetland and Water Crossing Permits and the EIS Scoping Dear Mr. Callan, As a sovereign nation with regulatory authority over downstream waters within the Bad River Watershed, on-Reservation air quality, and an interest in the use and enjoyment of the sacred waters of Anishinaabeg-Gichigami, or Lake Superior, pursuant to treaties we signed with the United States, we submit our comments related to the potential Line 5 Reroute around the Bad River Reservation proposed by Enbridge Energy, LLC (henceforth, “company” or “applicant”). The Bad River Band of Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians (henceforth, “Tribe”) is a federally-recognized Indian Tribe centered on the northern shores of Wisconsin and Madeline Island, where the Bad River Indian Reservation is located, but the Tribe also retains interest in ceded lands in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota. These lands were ceded to the United States government in the Treaties of 18371, 18422, and 18543. The proposed Line 5 Reroute falls within these ceded lands where the Tribe has retained usufructuary rights to use treaty resources. In addition, it threatens the water quality of the Tribe’s waters downstream, over which the Tribe has regulatory authority as a sovereign nation and as delegated by the federal government under the Clean Water Act. -

14-Bad-Montreal BCA Regional Unit Background Chapter

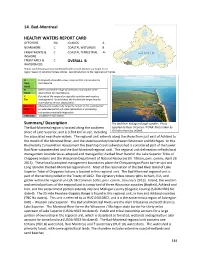

14. Bad-Montreal HEALTHY WATERS REPORT CARD OFFSHORE NA ISLANDS A NEARSHORE C COASTAL WETLANDS B EMBAYMENTS & C COASTAL TERRESTRIAL A+ INSHORE TRIBUTARIES & C OVERALL B WATERSHEDS Report card denotes general condition/health of each biodiversity target in the region based on condition/stress indices. See introduction to the regional summaries. A Ecologically desirable status; requires little intervention for Very maintenance Good B Within acceptable range of variation; may require some Good intervention for maintenance. C Outside of the range of acceptable variation and requires Fair management. If unchecked, the biodiversity target may be vulnerable to serious degradation. D Allowing the biodiversity target to remain in this condition for Poor an extended period will make restoration or preventing extirpation practically impossible. Unknown Insufficient information. Summary/ Description The Bad River Kakagon Slough complex. Photo The Bad-Montreal region is located along the southern supplied by Ryan O’Connor, WDNR. Photo taken by shore of Lake Superior, and is 3,764 km2 in size, including Christina Isenring, WDNR. the associated nearshore waters. The regional unit extends along the shore from just east of Ashland to the mouth of the Montreal River, and the state boundary line between Wisconsin and Michigan. In this Biodiversity Conservation Assessment the Beartrap Creek subwatershed is considered part of the Lower Bad River subwatershed and the Bad-Montreal regional unit. This regional unit delineation reflects local management boundaries as adopted and managed by the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (N. Tillison, pers. comm., April 26 2013). -

Wisconsin's Wetland Gems

100 WISCONSIN WETLAND GEMS ® Southeast Coastal Region NE-10 Peshtigo River Delta o r SC-1 Chiwaukee Prairie NE-11 Point Beach & Dunes e i SC-2 Des Plaines River NE-12 Rushes Lake MINNESOTA k e r a p Floodplain & Marshes NE-13 Shivering Sands & L u SC-3 Germantown Swamp Connected Wetlands S SC-4 Renak-Polak Woods NE-14 West Shore Green Bay SU-6 SU-9 SC-5 Root River Riverine Forest Wetlands SU-8 SU-11 SC-6 Warnimont Bluff Fens NE-15 Wolf River Bottoms SU-1 SU-12 SU-3 SU-7 Southeast Region North Central Region SU-10 SE-1 Beulah Bog NC-1 Atkins Lake & Hiles Swamp SU-5 NW-4 SU-4 SE-2 Cedarburg Bog NC-2 Bear Lake Sedge Meadow NW-2 NW-8 MICHIGAN SE-3 Cherokee Marsh NC-3 Bogus Swamp NW-1 NW-5 SU-2 SE-4 Horicon Marsh NC-4 Flambeau River State Forest NW-7 SE-5 Huiras Lake NC-11 NC-12 NC-5 Grandma Lake NC-9 SE-6 Lulu Lake NC-6 Hunting River Alders NW-10 NC-13 SE-7 Milwaukee River NC-7 Jump-Mondeaux NC-8 Floodplain Forest River Floodplain NW-6 NC-10 SE-8 Nichols Creek NC-8 Kissick Alkaline Bog NW-3 NC-5 NW-9 SE-9 Rush Lake NC-9 Rice Creek NC-4 NC-1 SE-10 Scuppernong River Area NC-10 Savage-Robago Lakes NC-2 NE-7 SE-11 Spruce Lake Bog NC-11 Spider Lake SE-12 Sugar River NC-12 Toy Lake Swamp NC-6 NC-7 Floodplain Forest NC-13 Turtle-Flambeau- NC-3 NE-6 SE-13 Waubesa Wetlands Manitowish Peatlands W-7 NE-9 WISCONSIN’S WETLAND GEMS SE-14 White River Marsh NE-2 Northwest Region NE-8 Central Region NE-10 NE-4 NW-1 Belden Swamp W-5 NE-12 WH-5 Mink River Estuary—Clint Farlinger C-1 Bass Lake Fen & Lunch NW-2 Black Lake Bog NE-13 NE-14 ® Creek Sedge Meadow NW-3 Blomberg Lake C-4 WHAT ARE WETLAND GEMS ? C-2 Bear Bluff Bog NW-4 Blueberry Swamp WH-2WH-7 C-6 NE-15 NE-1 Wetland Gems® are high quality habitats that represent the wetland riches—marshes, swamps, bogs, fens and more— C-3 Black River NW-5 Brule Glacial Spillway W-1 WH-2 that historically made up nearly a quarter of Wisconsin’s landscape. -

A Journey to the Wetlands of the Penokee Hills, Caroline Lake, and the Kakagon/Bad River Sloughs

A Journey to the Wetlands of the Penokee Hills, Caroline Lake, and the Kakagon/Bad River Sloughs Join Wisconsin Wetlands Association’s Executive Director Tracy Hames and the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa on this 2-day journey to one of Wisconsin’s highest quality and most threatened watersheds. This top-to-bottom tour will introduce you to the wetland resources of the Bad River Watershed. We will explore headwater wetlands in the Penokee Hills at the site of a proposed iron mine, and visit the tribe’s extensive wild rice beds in the internationally-recognized Kakagon/Bad River Sloughs estuary along the shores of Lake Superior. We will discuss the role these wetlands play regulating the water throughout the watershed, the importance of these wetlands and rice beds to the Bad River People, and the potential impacts to these resources of a proposed iron mine. Choose from three tours: Tour 1 July 17-18, 2014 Tour 2 July 23-24, 2014 Tour 3 September 18-19, 2014 Tour Guides: Tracy Hames, Executive Director, Wisconsin Wetlands Association (all three tours) Mike Wiggins, Jr., Tribal Chairman, Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa (first tour) Naomi Tillison, Water Program Director, Bad River Tribal Natural Resources (2nd & 3rd tour) Cinnamon fern in upper watershed wetland (photo by Tracy Hames) Itinerary (subject to adjustment as needed) We’ll be traveling to the Penokee Hills the morning of first day of each tour and visiting the upper watershed in the afternoon. That evening we’ll have dinner at the Deepwater Grille in Ashland. -

Federal Register/Vol. 76, No. 93/Friday, May 13, 2011/Notices

28074 Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 93 / Friday, May 13, 2011 / Notices Lac du Flambeau Reservation of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians of DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Wisconsin; Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin; Lac du Flambeau Band of Wisconsin; Oneida Tribe of Indians of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians of the National Park Service Wisconsin; Red Cliff Band of Lake Lac du Flambeau Reservation of [2253–665] Superior Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin; Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin; St. Croix Chippewa Indians Wisconsin; Red Cliff Band of Lake Notice of Inventory Completion: Utah of Wisconsin; Sokaogon Chippewa Superior Chippewa Indians of Museum of Natural History, Salt Lake Community, Wisconsin; and Wisconsin; St. Croix Chippewa City, UT Stockbridge Munsee Community, Community, Wisconsin; and Sokaogon Wisconsin. AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. Chippewa Community, Wisconsin. In 1968 or earlier, human remains ACTION: Notice. representing a minimum of one Representatives of any other Indian individual were recovered during tribe that believes itself to be culturally Notice is here given in accordance installation of a septic tank with a affiliated with the human remains with the Native American Graves backhoe at the Pine Point Resort, should contact William Green, Director, Protection and Repatriation Act Pickerel Lake, Ainsworth, Langlade Logan Museum of Anthropology, Beloit (NAGPRA), 25 U.S.C. 3003, of the County, WI. The remains were recorded College, Beloit, WI 53511, telephone completion of an inventory of human remains in the possession and control of as ‘‘Historic Indian,’’ suggesting funerary (608) 363–2119, fax (608) 363–7144, the Utah Museum of Natural History, objects may have been present, although before June 13, 2011. -

Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance

The Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Ramsar Convention What Ramsar Is: Who can nominate a site stakeholders associated with the proposed site greatly contribute to • In 1971, an international convention • Any local government, group, the nomination process; and was held in Ramsar, Iran and community, private organization, participants signed a treaty entitled, or landowner can nominate a A completed Ramsar Information “The Convention on Wetlands of site for inclusion on the Ramsar Sheet, is available online at http://bit. International Importance, Especially List of Wetlands of International ly/1HIU7PR as Waterfowl Habitat.” Importance. The Federal government can also nominate sites, such as Nine Criteria for “Wetlands • The Ramsar Convention provides a National Parks, National Forests, or of International Importance” framework for voluntary international National Wildlife Refuges. Designation: cooperation for wetland conservation. A wetland should be considered • A written agreement is required internationally important if it meets • The U.S. acceded to the Ramsar from all landowners and a Member Convention April 18, 1987. any one of the following criteria. The of Congress representing the site: geographic area. What Ramsar Does: 1. contains a representative, rare, • Recognizes wetlands’ importance to Nomination package or unique example of a natural communities, cultures, governments, The petitioner must submit a complete or near-natural wetland type and businesses and encourages nomination package to the Director, found within the appropriate wetland conservation and wise use of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), biogeographic region; or wetlands. 1849 C Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20006, with a copy to the Global 2. supports vulnerable, endangered, • Establishes criteria for designating Program, Division of International or critically endangered species rivers, marshes, coral reefs and other Conservation, FWS. -

Enbridge Line 5 Brochure

Published: February 2020 Enbridge Line 5 Issues Within the Bad River Reservation ~A Brief Overview Provided by Mashkiiziibii Natural Resources Department~ n 1953, Lakehead Pipeline Company installed a pipeline to transport crude oil across the Bad River Reser- I vation and in adjacent areas. This pipeline is now called Enbridge Line 5. In January 2017, the Tribal Council passed a resolution to state that the Tribe would not be renewing it’s interests in the rights of way across the Bad River Reservation and to direct the removal of the Enbridge Line 5 pipeline from the entire Bad River Watershed. In October 2019, the Tribal Council passed another resolution reiterating their 2017 deci- sion. Over the last couple of years, the Mashkiiziibii Natural Resources Department (MNRD) has increased its ef- forts to better understand the impacts and threats of Enbridge Line 5 pipeline on our waters, wildlife, fisher- ies, plants, and other natural resources. This special newsletter edition highlights five areas across the Reser- vation where MNRD has the most concerns about Enbridge Line 5 impacts and threats. These five areas are not the only areas on the Reservation that are impacted and/or threatened by Line 5. Link to view Resolutions: http://www.badriver-nsn.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Pipeline_Resolution_Line5_Removal_2017.pdf http://www.badriver-nsn.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/NRD_EnbridgeRemoval_Resolution_201910.pdf Mashkiiziibii Natural Resources Department (MNRD) has responded to numerous threats posed by Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline. -

Wild Rice 3 Superbugs Examining Its Genetic Makeup May Reveal Critical& Evidence to Aid Restoration

Winter 2009 Aquatic Sciences Chronicle ASCwww.aqua.wisc.edu/chronicle UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN SEA GRANT INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN WATER RESOURCES INSTITUTE INSIDE: SEA GRANT RESEARCH “fingerprinting” Wild rice 3 SUPERBUGS EXAMINING ITS GENETIC MAKEUP MAY REVEAL CRITICAL& EVIDENCE TO AID RESTORATION 4 AQUALOG 5 TEACHERS AND THE GUARDIAN photo by Tim Tynan Tim photo by Tribal members from Wild rice was once so abundant in Wisconsin that it gave its name to the Bad River Band many bodies of water throughout the state. One or more “Rice Lakes” of Lake Superior are located in 21 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties, but today many of them are Chippewa (Ojibwe) rice lakes in name only. Since the settlement of Europeans, people have harvest wild rice on altered the landscape and made it diffi cult for the plant to succeed. the Kakagon Sloughs Along the shores of Lake Superior and Lake Michigan, wild rice has near Ashland, the only large, pristine coastal suffered a similar fate. Today, just one large population remains—on population of wild rice the Lake Superior shore of Ashland County—along with a few other remaining in the entire small, remnant populations scattered around the Wisconsin coastline. A Great Lakes region. Sea Grant-funded researcher is examining the genetic makeup of these remaining populations to fi nd out how to preserve the identity of wild rice while expanding its distribution along the Lake Superior and Lake Michigan coastlines. Anthony Kern is a plant geneticist at Northland College in Ashland, Wis. He said that in coastal habitats, wild rice (Zizania palustris) thrives in shallow water with a current and silty bottom—typically at the mouths of river estuaries. -

U.S. Wetlands Need a Strategic Approach for Ramsar Nominations

U.S. Wetlands Need a Strategic Approach for Ramsar Nominations The United States remains far behind many other countries in the number of wetlands designated by the Ramsar Convention as Wetlands of International Importance. The author argues that a strategic approach to nominating Ramsar sites will be essential to helping U.S. wetlands realize the many benefits that a Ramsar designation provides. By Katie Beilfuss n February 2012, the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands added Ramsar Conference of the Contracting Parties (COP11) in July four new wetlands in the United States to the official list of 2012 in Bucharest, Romania. Wetlands of International Importance: the Congaree National WWA’s outreach focuses on promoting wetlands as valuable Park (South Carolina), the Emiquon Complex (Illinois), the resources, both to the general public and to target audiences, IKakagon and Bad River Sloughs (Wisconsin), and the Sue and Wes including policymakers, local land use officials, and watershed Dixon Waterfowl Refuge at Hennepin & Hopper Lakes (Illinois). advocates. In our experience, the public still holds a negative (See the sidebar at the end of this article for more background on the stereotype of wetlands. They are “wastelands.” They breed mos- Ramsar Convention and Wetlands of International Importance.) De- quitoes and other pests. They stand in the way of development. spite these new additions, the United States remains behind many Even in daily conversation, this important natural resource is of our neighbors and partners in the number of designated sites beleaguered: people complain about “bogged down” processes or within our borders. We are missing an important and underutilized “swamped” workloads. -

![EDF and Other Ngos [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9325/edf-and-other-ngos-pdf-2519325.webp)

EDF and Other Ngos [PDF]

USCA Case #16-1127 Document #1660822 Filed: 02/10/2017 Page 1 of 28 ORAL ARGUMENT NOT YET SCHEDULED No. 16-1127 (and consolidated cases) UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT ______________________________________ MURRAY ENERGY CORPORATION, et al. Petitioners, v. UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY, et al. Respondents. ____________________________________ On Petition for Review of Final Agency Action of the United States Environmental Protection Agency, 81 Fed. Reg. 24,420 (Apr. 25, 2016) ____________________________________ BRIEF OF NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATION INTERVENORS ____________________________________ NEIL GORMLEY SEAN H. DONAHUE JAMES S. PEW Donahue & Goldberg, LLP Earthjustice 1111 14th Street, N.W., Suite 510A 1625 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20005 Suite 702 (202) 277-7085 Washington, DC 20036 [email protected] (202) 667-4500 PAMELA A. CAMPOS Counsel for Chesapeake Bay Foundation, GRAHAM G. MCCAHAN Chesapeake Climate Action Network, VICKIE L. PATTON Clean Air Council, Downwinders at Risk, Environmental Defense Fund Environmental Integrity Project, 2060 Broadway, Suite 300 National Association for the Boulder, CO 80302 Advancement of Colored People, and (303) 447-7228 the Sierra Club Counsel for Environmental Defense Fund Additional Counsel Listed On Signature Block. USCA Case #16-1127 Document #1660822 Filed: 02/10/2017 Page 2 of 28 CERTIFICATE AS TO PARTIES, RULINGS, AND RELATED CASES Pursuant to Circuit Rule 28(a)(1), Respondent-Intervenors American Lung Association, -

Examining Historical Mercury Sources in the Saint Louis River Estuary: How Legacy Contamination Influences Biological Mercury Levels in Great Lakes Coastal Regions

Science of the Total Environment 779 (2021) 146284 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Examining historical mercury sources in the Saint Louis River estuary: How legacy contamination influences biological mercury levels in Great Lakes coastal regions Sarah E. Janssen a,⁎, Joel C. Hoffman b, Ryan F. Lepak b,c, David P. Krabbenhoft a, David Walters d, Collin A. Eagles-Smith e, Greg Peterson b, Jacob M. Ogorek a, John F. DeWild a, Anne Cotter b, Mark Pearson b, Michael T. Tate a, Roger B. Yeardley Jr. f, Marc A. Mills f a U.S. Geological Survey Upper Midwest Water Science Center, 8505 Research Way, Middleton, WI 53562, USA b U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development, Center for Computational Toxicology and Exposure, Great Lakes Toxicology and Ecology Division, 6201 Congdon Blvd, Duluth, MN 55804, USA c Environmental Chemistry and Technology Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 660 N. Park Street, Madison, WI 53706, USA d U.S. Geological Survey Columbia Environmental Research Center, 4200 New Haven Rd, Columbia, MO 65201, USA e U.S. Geological Survey, Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, 3200SW Jefferson Way, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA f U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development, Center for Environmental Solutions and Emergency Response, Cincinnati, OH 45220, USA HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT • Legacy Hg contamination is still actively cycling in a coastal Great Lakes food web. • Aquatic and riparian consumers display overlappingHgisotopevalues. • Dietary trophic gradients within the estu- ary produced Hg isotope shifts in fish. -

Legacy Places by County

Buffalo County SL Shoveler Lakes-Black Earth Trench Fond du Lac County Jefferson County Legacy Places BU Buffalo River SG Sugar River CD Campbellsport Drumlins BK Bark and Scuppernong Rivers CY Cochrane City Bluffs UL Upper Yahara River and Lakes GH Glacial Habitat Restoration Area CW Crawfish River-Waterloo Drumlins by County Lower Chippewa River and Prairies Horicon Marsh Jefferson Marsh LC Dodge County HM JM TR Trempealeau River KM Kettle Moraine State Forest KM Kettle Moraine State Forest Crawfish River-Waterloo Drumlins UM Upper Mississippi River National CW MI Milwaukee River LK Lake Koshkonong to Kettle Glacial Habitat Restoration Area Adams County Wildlife and Fish Refuge GH NE Niagara Escarpment Moraine Corridor Horicon Marsh CG Central Wisconsin Grasslands HM SY Sheboygan River Marshes UR Upper Rock River Niagara Escarpment CU Colburn-Richfield Wetlands Burnett County NE Upper Rock River MW Middle Wisconsin River CA Chase Creek UR Forest County Juneau County Clam River Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forests Badlands NN Neenah Creek CR Door County CN BN CX Crex Meadows LH Laona Hemlock Hardwoods BO Baraboo River QB Quincy Bluff and Wetlands Chambers Island DS Danbury to Sterling Corridor CI PE Peshtigo River CF Central Wisconsin Forests Colonial Waterbird Nesting Islands Ashland County NB Namekagon-Brule Barrens CS UP Upper Wolf River GC Greensand Cuesta Door Peninsula Hardwood Swamps AI Apostle Islands NR Namekagon River DP LL Lower Lemonweir River Eagle Harbor to Toft Point Corridor BD Bad River SX St. Croix River EH Grant County