Development of a Heterodyne Laser Interferometer for Very Small High Frequency Displacements Detection. Diploma Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward a Large Bandwidth Photonic Correlator for Infrared Heterodyne Interferometry a first Laboratory Proof of Concept

A&A 639, A53 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201937368 & c G. Bourdarot et al. 2020 Astrophysics Toward a large bandwidth photonic correlator for infrared heterodyne interferometry A first laboratory proof of concept G. Bourdarot1,2, H. Guillet de Chatellus2, and J-P. Berger1 1 Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, 38000 Grenoble, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, LIPHY, 38000 Grenoble, France Received 19 December 2019 / Accepted 17 May 2020 ABSTRACT Context. Infrared heterodyne interferometry has been proposed as a practical alternative for recombining a large number of telescopes over kilometric baselines in the mid-infrared. However, the current limited correlation capacities impose strong restrictions on the sen- sitivity of this appealing technique. Aims. In this paper, we propose to address the problem of transport and correlation of wide-bandwidth signals over kilometric dis- tances by introducing photonic processing in infrared heterodyne interferometry. Methods. We describe the architecture of a photonic double-sideband correlator for two telescopes, along with the experimental demonstration of this concept on a proof-of-principle test bed. Results. We demonstrate the a posteriori correlation of two infrared signals previously generated on a two-telescope simulator in a double-sideband photonic correlator. A degradation of the signal-to-noise ratio of 13%, equivalent to a noise factor NF = 1:15, is obtained through the correlator, and the temporal coherence properties of our input signals are retrieved from these measurements. Conclusions. Our results demonstrate that photonic processing can be used to correlate heterodyne signals with a potentially large increase of detection bandwidth. -

Army Radio Communication in the Great War Keith R Thrower, OBE

Army radio communication in the Great War Keith R Thrower, OBE Introduction Prior to the outbreak of WW1 in August 1914 many of the techniques to be used in later years for radio communications had already been invented, although most were still at an early stage of practical application. Radio transmitters at that time were predominantly using spark discharge from a high voltage induction coil, which created a series of damped oscillations in an associated tuned circuit at the rate of the spark discharge. The transmitted signal was noisy and rich in harmonics and spread widely over the radio spectrum. The ideal transmission was a continuous wave (CW) and there were three methods for producing this: 1. From an HF alternator, the practical design of which was made by the US General Electric engineer Ernst Alexanderson, initially based on a specification by Reginald Fessenden. These alternators were primarily intended for high-power, long-wave transmission and not suitable for use on the battlefield. 2. Arc generator, the practical form of which was invented by Valdemar Poulsen in 1902. Again the transmitters were high power and not suitable for battlefield use. 3. Valve oscillator, which was invented by the German engineer, Alexander Meissner, and patented in April 1913. Several important circuits using valves had been produced by 1914. These include: (a) the heterodyne, an oscillator circuit used to mix with an incoming continuous wave signal and beat it down to an audible note; (b) the detector, to extract the audio signal from the high frequency carrier; (c) the amplifier, both for the incoming high frequency signal and the detected audio or the beat signal from the heterodyne receiver; (d) regenerative feedback from the output of the detector or RF amplifier to its input, which had the effect of sharpening the tuning and increasing the amplification. -

Lecture 25 Demodulation and the Superheterodyne Receiver EE445-10

EE447 Lecture 6 Lecture 25 Demodulation and the Superheterodyne Receiver EE445-10 HW7;5-4,5-7,5-13a-d,5-23,5-31 Due next Monday, 29th 1 Figure 4–29 Superheterodyne receiver. m(t) 2 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. 0-13-142492-0 1 EE447 Lecture 6 Synchronous Demodulation s(t) LPF m(t) 2Cos(2πfct) •Only method for DSB-SC, USB-SC, LSB-SC •AM with carrier •Envelope Detection – Input SNR >~10 dB required •Synchronous Detection – (no threshold effect) •Note the 2 on the LO normalizes the output amplitude 3 Figure 4–24 PLL used for coherent detection of AM. 4 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. 0-13-142492-0 2 EE447 Lecture 6 Envelope Detector C • Ac • (1+ a • m(t)) Where C is a constant C • Ac • a • m(t)) 5 Envelope Detector Distortion Hi Frequency m(t) Slope overload IF Frequency Present in Output signal 6 3 EE447 Lecture 6 Superheterodyne Receiver EE445-09 7 8 4 EE447 Lecture 6 9 Super-Heterodyne AM Receiver 10 5 EE447 Lecture 6 Super-Heterodyne AM Receiver 11 RF Filter • Provides Image Rejection fimage=fLO+fif • Reduces amplitude of interfering signals far from the carrier frequency • Reduces the amount of LO signal that radiates from the Antenna stop 2/22 12 6 EE447 Lecture 6 Figure 4–30 Spectra of signals and transfer function of an RF amplifier in a superheterodyne receiver. 13 Couch, Digital and Analog Communication Systems, Seventh Edition ©2007 Pearson Education, Inc. -

Design Considerations for Optical Heterodyne

DESIGNCONSIDERATIONS FOR OPTICAL HETERODYNERECEIVERS: A RFXIEW John J. Degnan Instrument Electro-optics Branch NASA GoddardSpace Flight Center Greenbelt,Maryland 20771 ABSTRACT By its verynature, an optical heterodyne receiver is both a receiver and anantenna. Certain fundamental antenna properties ofheterodyne receivers are describedwhich set theoretical limits on the receiver sensitivity for the detectionof coherent point sources, scattered light, and thermal radiation. In order to approachthese limiting sensitivities, the geometry of the optical antenna-heterodyne receiver configurationmust be carefully tailored to the intendedapplication. The geometric factors which affect system sensitivity includethe local osciliator (LO) amplitudedistribution, mismatches between the signaland LO phasefronts,central obscurations of the optical antenna, and nonuniformmixer quantum efficiencies. The current state of knowledge in this area, which rests heavilyon modern concepts of partial coherence, is reviewed. Following a discussion of noiseprocesses in the heterodyne receiver and the manner in which sensitivity is increasedthrough time integration of the detectedsignal, we derivean expression for the mean squaresignal current obtained by mixing a coherent local oscillator with a partially coherent, quasi- monochromaticsource. We thendemonstrate the manner in which the IF signal calculationcan be transferred to anyconvenient plane in the optical front end ofthe receiver. Using these techniques, we obtain a relativelysimple equation forthe coherently detected signal from anextended incoherent source and apply it to theheterodyne detection of an extended thermal source and to theback- scatter lidar problem where the antenna patternsof both the transmitter beam andheterodyne receiver mustbe taken into account. Finally, we considerthe detectionof a coherentsource and, in particular, a distantpoint source such as a star or laser transmitter in a longrange heterodyne communications system. -

Heterodyne Detector for Measuring the Characteristic of Elliptically Polarized Microwaves

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Oct 02, 2021 Heterodyne detector for measuring the characteristic of elliptically polarized microwaves Leipold, Frank; Nielsen, Stefan Kragh; Michelsen, Susanne Published in: Review of Scientific Instruments Link to article, DOI: 10.1063/1.2937651 Publication date: 2008 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Leipold, F., Nielsen, S. K., & Michelsen, S. (2008). Heterodyne detector for measuring the characteristic of elliptically polarized microwaves. Review of Scientific Instruments, 79(6), 065103. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2937651 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. REVIEW OF SCIENTIFIC INSTRUMENTS 79, 065103 ͑2008͒ Heterodyne detector for measuring the characteristic of elliptically polarized microwaves Frank Leipold, Stefan Nielsen, and Susanne Michelsen Association EURATOM, Risø National Laboratory, Technical University of Denmark, OPL-128, Frederiksborgvej 399, 4000 Roskilde, Denmark ͑Received 28 January 2008; accepted 6 May 2008; published online 4 June 2008͒ In the present paper, a device is introduced, which is capable of determining the three characteristic parameters of elliptically polarized light ͑ellipticity, angle of ellipticity, and direction of rotation͒ for microwave radiation at a frequency of 110 GHz. -

Before Valve Amplification) Page 1 of 15 Before Valve Amplification - Wireless Communication of an Early Era

(Before Valve Amplification) Page 1 of 15 Before Valve Amplification - Wireless Communication of an Early Era by Lloyd Butler VK5BR At the turn of the century there were no amplifier valves and no transistors, but radio communication across the ocean had been established. Now we look back and see how it was done and discuss the equipment used. (Orininally published in the journal "Amateur Radio", July 1986) INTRODUCTION In the complex electronics world of today, where thousands of transistors junctions are placed on a single silicon chip, we regard even electron tube amplification as being from a bygone era. We tend to associate the early development of radio around the electron tube as an amplifier, but we should not forget that the pioneers had established radio communications before that device had been discovered. This article examines some of the equipment used for radio (or should we say wireless) communications of that day. Discussion will concentrate on the equipment used and associated circuit descriptions rather than the history of its development. Anyone interested in history is referred to a thesis The Historical Development of Radio Communications by J R Cox VK6NJ published as a series in Amateur Radio, from December 1964 to June 1965. Over the years, some of the early terms used have given-way to other commonly used ones. Radio was called wireless, and still is to some extent. For example, it is still found in the name of our own representative body, the W1A. Electro Magnetic (EM) Waves were called hertzian waves or ether waves and the medium which supported them was known as the ether. -

A Polarization-Insensitive Recirculating Delayed Self-Heterodyne Method for Sub-Kilohertz Laser Linewidth Measurement

hv photonics Communication A Polarization-Insensitive Recirculating Delayed Self-Heterodyne Method for Sub-Kilohertz Laser Linewidth Measurement Jing Gao 1,2,3 , Dongdong Jiao 1,3, Xue Deng 1,3, Jie Liu 1,3, Linbo Zhang 1,2,3 , Qi Zang 1,2,3, Xiang Zhang 1,2,3, Tao Liu 1,3,* and Shougang Zhang 1,3 1 National Time Service Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi’an 710600, China; [email protected] (J.G.); [email protected] (D.J.); [email protected] (X.D.); [email protected] (J.L.); [email protected] (L.Z.); [email protected] (Q.Z.); [email protected] (X.Z.); [email protected] (S.Z.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100039, China 3 Key Laboratory of Time and Frequency Standards, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi’an 710600, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-29-8389-0519 Abstract: A polarization-insensitive recirculating delayed self-heterodyne method (PI-RDSHM) is proposed and demonstrated for the precise measurement of sub-kilohertz laser linewidths. By a unique combination of Faraday rotator mirrors (FRMs) in an interferometer, the polarization-induced fading is effectively reduced without any active polarization control. This passive polarization- insensitive operation is theoretically analyzed and experimentally verified. Benefited from the recirculating mechanism, a series of stable beat spectra with different delay times can be measured simultaneously without changing the length of delay fiber. Based on Voigt profile fitting of high- order beat spectra, the average Lorentzian linewidth of the laser is obtained. The PI-RDSHM has advantages of polarization insensitivity, high resolution, and less statistical error, providing an Citation: Gao, J.; Jiao, D.; Deng, X.; effective tool for accurate measurement of sub-kilohertz laser linewidth. -

History of Naval Ships Wireless Systems I

History of Naval Ships Wireless Systems I 1890’s to the 1920’s Wireless telegraphy was introduced in to the RN in 1897 by Marconi and Captain HB Jackson, a Torpedo specialist. There was no way to measure wavelength and tuning was in its infancy. Transmission was achieved by use of a spark gap transmitter and the frequency was dependent upon the size and configuration of the aerial. As a result, there was only one wireless channel as the electromagnetic energy leaving the antenna would cover an extremely wide frequency band. The receiver consisted of a similar aerial and the use of a "coherer" which detected EM waves. A battery operated circuit then operated a telegraph "inker" which displayed the signal visually on tape. There was no means of tuning the receiver except to make the aerial the same size as that of the transmitter. It could not distinguish between atmospherics and signals and if two stations transmitted at once, the result was a jumble of unintelligible marks on the tape. There was a notable characteristic about the spark gap transmitter. On reception, each signal sounded just a little bit different than the rest. This signal characteristic was usually determined by electrode gap spacings, electrode shapes, and power levels inherent to each transmitter. With a little practice, one could attach an identity to the transmitting station based on the sound in the headphones. From a security viewpoint, this was not good for any navy, as a ship could eventually be identified by the tone of its transmitted signal. On the other hand, this signal trait was a blessing, otherwise, there would have been no hope of communication as 'spark' produced signals were extremely wide. -

A Short History of Radio

Winter 2003-2004 AA ShortShort HistoryHistory ofof RadioRadio With an Inside Focus on Mobile Radio PIONEERS OF RADIO If success has many fathers, then radio • Edwin Armstrong—this WWI Army officer, Columbia is one of the world’s greatest University engineering professor, and creator of FM radio successes. Perhaps one simple way to sort out this invented the regenerative circuit, the first amplifying re- multiple parentage is to place those who have been ceiver and reliable continuous-wave transmitter; and the given credit for “fathering” superheterodyne circuit, a means of receiving, converting radio into groups. and amplifying weak, high-frequency electromagnetic waves. His inventions are considered by many to provide the foundation for cellular The Scientists: phones. • Henirich Hertz—this Clockwise from German physicist, who died of blood poisoning at bottom-Ernst age 37, was the first to Alexanderson prove that you could (1878-1975), transmit and receive Reginald Fessin- electric waves wirelessly. den (1866-1932), Although Hertz originally Heinrich Hertz thought his work had no (1857-1894), practical use, today it is Edwin Armstrong recognized as the fundamental (1890-1954), Lee building block of radio and every DeForest (1873- frequency measurement is named 1961), and Nikola after him (the Hertz). Tesla (1856-1943). • Nikola Tesla—was a Serbian- Center color American inventor who discovered photo is Gug- the basis for most alternating-current lielmo Marconi machinery. In 1884, a year after (1874-1937). coming to the United States he sold The Businessmen: the patent rights for his system of alternating- current dynamos, transformers, and motors to George • Guglielmo Marconi—this Italian crea- Westinghouse. -

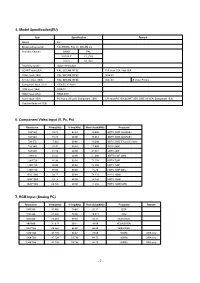

7. RGB Input (Analog PC)

5. Model Specification(EU) Item Specification Remark Market EU Broadcasting system PAL BG/DK, PAL I/II, SECAM L/L’ Available Channel BAND PAL VHF/UHF C1_C69 CATV S1_S47 Receiving system Upper Heterodyne SCART Input(2EA) PAL, SECAM, NTSC Full Scart 1EA, Harf 1EA Video Input (1EA) PAL, SECAM, NTSC Side AV S-Video Input (1EA) PAL, SECAM, NTSC Side AV S-Video Priority Component Input (1EA) Y/Cb/Cr, Y/ Pb/Pr RGB Input (1EA) RGB-PC HDMI Input (2EA) HDMI-DTV Audio Input (4EA) PC Audio, AV (3A), Component (1EA) L/R Input(PC 1EA,SCART 2EA, SIDE AV 1EA, Component 1EA) Variable Audio out(1EA) 6. Component Video Input (Y, PB, PR) Resolution H-freq(kHz) V-freq(kHz) Pixel clock(MHz) Proposed 720*480 15.73 59.94 13.500 SDTV, DVD 480I(525I) 720*480 15.75 60.00 13.514 SDTV, DVD 480I(525I) 720*576 15.625 50.00 13.500 SDTV, DVD 576I(625I) 50Hz 720*480 31.47 59.94 27.000 SDTV 480P 720*480 31.50 60.00 27.027 SDTV 480P 720*576 31.25 50.00 27.000 SDTV 576P 50Hz 1280*720 44.96 59.94 74.176 HDTV 720P 1280*720 45.00 60.00 74.250 HDTV 720P 1280*720 37.50 50.00 74.25 HDTV 720P 50Hz 1920*1080 33.72 59.94 74.176 HDTV 1080I 1920*1080 33.75 60.00 74.250 HDTV 1080I 1920*1080 28.125 50.00 74.250 HDTV 1080I 50Hz 7. RGB Input (Analog PC) Resolution H-freq(kHz) V-freq(kHz) Pixel clock(MHz) Proposed Remark 640*350 31.468 70.80 25.17 EGA 720*400 31.469 70.80 28.321 DOS 640*480 31.469 59.94 25.17 VESA(VGA) 800*600 37.879 60.31 40.00 VESA(SVGA) 1024*768 48.363 60.00 65.00 VESA(XGA) 1280*768 47.776 59.87 79.50 WXGA XGA only 1360*768 47.720 59.799 84.75 WXGA XGA only 1366*768 47.720 59.799 84.75 WXGA XGA only - 7 - 8. -

Heterodyne Sensing of Microwaves with a Quantum Sensor

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22714-y OPEN Heterodyne sensing of microwaves with a quantum sensor ✉ ✉ Jonas Meinel 1,2 , Vadim Vorobyov 1 , Boris Yavkin1, Durga Dasari 1,2, Hitoshi Sumiya3, ✉ Shinobu Onoda 4, Junichi Isoya 5 & Jörg Wrachtrup1,2 Diamond quantum sensors are sensitive to weak microwave magnetic fields resonant to the spin transitions. However, the spectral resolution in such protocols is ultimately limited by the 1234567890():,; sensor lifetime. Here, we demonstrate a heterodyne detection method for microwaves (MW) leading to a lifetime independent spectral resolution in the GHz range. We reference the MW signal to a local oscillator by generating the initial superposition state from a coherent source. Experimentally, we achieve a spectral resolution below 1 Hz for a 4 GHz signal far below the sensor lifetime limit of kilohertz. Furthermore, we show control over the interaction of the MW-field with the two-level system by applying dressing fields, pulsed Mollow absorption and Floquet dynamics under strong longitudinal radio frequency drive. While pulsed Mollow absorption leads to improved sensitivity, the Floquet dynamics allow robust control, independent from the system’s resonance frequency. Our work is important for future studies in sensing weak microwave signals in a wide frequency range with high spectral resolution. 1 3rd Institute of Physics, University of Stuttgart Institute for Quantum Science and Technology IQST, Stuttgart, Germany. 2 Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research, Stuttgart, Germany. 3 Advanced Materials Laboratory, Sumitomo Electric Industries Ltd., Itami, Japan. 4 Takasaki Advanced Radiation Research Institute, National Institutes for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology, Takasaki, Japan. -

AP-60-860A Agile Processor

AP-60-860A Agile Processor The AP-60-860A (Agile Digital/Analog Processor) operates in one of the three following modes: Mode 1: Analog Heterodyne Processor (Analog RF IN > Analog RF OUT) D Mode 2: Digital Heterodyne Processor (QAM IN > QAM OUT) I Mode 3: Digital-to-Analog Processor (8VSB or QAM IN > Analog RF OUT) G I Mode 1 Mode 2 Mode 3 T Analog RF QAM QAM/8VSB CATV Ch. T7-T13 A CATV Ch. 2-135 CATV Ch. 2-135 VHF Ch. 2-13 CATV Ch. T7-T13 VHF Ch. 2-13 L UHF Ch. 14-69 CATV Ch. 2-135 UHF Ch. 14-69 C O CATV Ch. 2-135 CATV Ch. 2-135 CATV Ch. 2-135 L L Analog RF QAM Analog RF E +60 dBmV +55 dBmV +60 dBmV C T Features I • As an agile analog heterodyne processor: accepts one Analog RF input (CATV sub-band channels T7-T13, CATV standard channels 2-135, VHF channels 2-13, and UHF channels 14-69) and delivers one Analog RF output (CATV standard channels 2-135) O • As an agile digital heterodyne processor: accepts one Digital Cable QAM input (CATV sub-band channels T7-T13, and CATV standard N channels 2-135) and delivers one Digital Cable QAM output (CATV standard channels 2-135) • As an agile digital-to-analog processor: accepts one Digital Off-air 8VSB or Digital Cable QAM input (CATV standard channels 2-135, VHF channels 2-13, and UHF channels 14-69) and delivers one Analog RF output (CATV standard channels 2-135) • Equipped with EAS interface which can also be used as an IF (Intermediate Frequency) input • Supports Closed Captioning (EIA-608) Ordering Information Model Stock # Description AP-60-860A 59819 Agile, Processor, +60 dBmV, 54-860 MHz output Related Products Model Description DAP Digital-to-Analog Processor; 1 RU AP Series Agile Heterodyne Processor; 1 RU Purchase from: www.multicominc.com 800-423-2594 407-331-7779 ® Rev.