The Role of Uganda's Service Reforms in Marketing and Agricultural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karamoja and Northern Uganda Comparative Analysis of Livelihood Recovery in the Post-Conflict Periods November 2019

Karamoja and Northern Uganda Comparative analysis of livelihood recovery in the post-conflict periods November 2019 Karamoja and Northern Uganda Comparative analysis of livelihood recovery in the post-conflict periods November 2019 Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Tufts University Rome, 2019 REQUIRED CITATION FAO and Tufts University. 2019. Comparative analysis of livelihood recovery in the post-conflict periods – Karamoja and Northern Uganda. November 2019. Rome. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) or Tufts University concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO or the University in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO or the University. ISBN 978-92-5-131747-1 (FAO) ©FAO and Tufts University, 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. -

Technical Assistance to the District Local Governments of Abim, Adjumani, Amudat and Moyo to Carry out Rehabilitation of District and Community Access Roads

PREPARED FOR: UNITED NATIONS CAPITAL DEVELOPMENT FUND (UNCDF) CONSULTING SERVICES: TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE TO THE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENTS OF ABIM, ADJUMANI, AMUDAT AND MOYO TO CARRY OUT REHABILITATION OF DISTRICT AND COMMUNITY ACCESS ROADS Contract No. 016-01-2019 INCEPTION REPORT APRIL 2019 SUBMITTED BY: Consulting Services: Technical Assistance to the District Local Governments Of Abim, Adjumani, Amudat and Moyo to Carry Out Rehabilitation of District and Community Access Roads – Final Inception Report TABLE OF CONTENT LIST OF FIGURES ___________________________________________________________________ iv LIST OF TABLES ____________________________________________________________________ v Document History _________________________________________________________________ vi List of Acronyms ___________________________________________________________________vii Executive Summary _______________________________________________________________ viii 1 Introduction __________________________________________________________________ 1 1.1 Project Background________________________________________________________________ 1 1.2 Location Map ____________________________________________________________________ 4 1.3 Project Details ____________________________________________________________________ 4 1.4 Objectives of Assignment ___________________________________________________________ 5 1.5 Scope of Services, Expected Output and Target Completion _______________________________ 5 1.6 Phase A: Detailed Engineering Designs ________________________________________________ -

Field Report Presentation

Consulting Services: Technical Assistance to the District Local Governments of Abim, Adjumani, Amudat and Moyo to carry out Rehabilitation of District and Community Access Roads Location map Field Report Presentation 17th April 2019 at MoWT Boardroom, Kampala By: Pietro Zelante (Team Leader/Senior Project Engineer) A project implemented by: 1 Consulting Services: Technical Assistance to the District Local Governments of Abim, Adjumani, Amudat and Moyo to carry out Rehabilitation of District and Community Access Roads Presentation Outline 1. Project Background 2.Introduction 3. Adjumani field findings 4. Moyo field findings 5. Abim field findings 6. Amudat field findings A project implemented by: 2 Consulting Services: Technical Assistance to the District Local Governments of Abim, Adjumani, Amudat and Moyo to carry out Rehabilitation of District and Community Access Roads Project Background The European Union through its 11th European Development Fund in collaboration with the Government of Uganda has launched the Development Initiative for Northern Uganda (DINU), an integrated development programme which aims at addressing, the key development challenges in the Northern Uganda. The region is faced with challenges: poverty, issues of good governance and democratic process to improve service delivery. DINU will implement activities aimed at unlocking trade within the region, country, and with neighboring countries through the improvement of transport infrastructures. A project implemented by: 3 Consulting Services: Technical Assistance to the District Local Governments of Abim, Adjumani, Amudat and Moyo to carry out Rehabilitation of District and Community Access Roads Introduction The Consultant carried out the consultations and field work from 18th to 28th March 2019. The field studies for the project roads commenced on the 18th, March 2019 from Adjumani district, then to Moyo district on the 20th March, then to Abim district on 25th March, and finally to Amudat district on 27th March 2019. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Livelihood Dynamics in Northern Karamoja

LIVELIHOOD DYNAMICS IN NORTHERN KARAMOJA A Participatory Baseline Study for the Growth Health and Governance Program John Burns – Gezu Bekele – Darlington Akabwai May 2013 II Table of Contents SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Research Background and Overview .................................................................................... 4 1.2 Research Questions .............................................................................................................. 5 2. METHODS .................................................................................................................................. 5 2.1 Study Overview ..................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Sampling ............................................................................................................................... 6 2.2.1 Method and Size ............................................................................................................. 6 2.3 Data Collection Methods ....................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Pre-Testing ........................................................................................................................... -

Killing the Goose That Lays the Golden Egg

KILLING THE GOOSE THAT LAYS THE GOLDEN EGG An Analysis of Budget Allocations and Revenue from the Environment and Natural Resource Sector in Karamoja Region Caroline Adoch Eugene Gerald Ssemakula ACODE Policy Research Series No.47, 2011 KILLING THE GOOSE THAT LAYS THE GOLDEN EGG An Analysis of Budget Allocations and Revenue from the Environment and Natural Resource Sector in Karamoja Region Caroline Adoch Eugene Gerald Ssemakula ACODE Policy Research Series No.47, 2011 Published by ACODE P. O. Box 29836, Kampala Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Adoch, C., and Ssemakula, E., (2011). Killing the Goose that Lays the Golden Egg: An Analysis of Budget Allocations and Revenue from the Environment and Natural Resource Sector in Karamoja Region. ACODE Policy Research Series, No. 47, 2011. Kampala. © ACODE 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations and grants from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purposes or for purposes of informing public policy is excluded from this restriction. ISBN 978997007077 Contents LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................. v LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................. -

KOTIDO District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profile August 2014

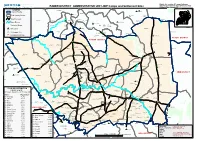

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA KARAMOJA KOTIDO District HAzArd, risk And VulnerAbility Profile August 2014 KOTIDO HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE | i With support from: United Nations Development Programme Plot 11, Yusuf Lule Road P.O. Box 7184 Kampala, Uganda For more information: www.undp.org ii | KOTIDO HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE Contents Acronyms.....................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgement........................................................................................................1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..............................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................... 3 Objectives...... .............................................................................................................3 Methodology ................................................................................................................3 Overview of the District ...............................................................................................6 Brief district history ..................................................................................................6 Location and administrative structure ......................................................................6 Ethnicity ....................................................................................................................6 -

Arcview Print

District, Sub counties, IDP camps, Settlement Sites,Transport Network, Rivers & Protected Areas PADER DISTRICT ADMINISTRATIVE UNIT- IDP Camps and Settlement Sites Reference Date: January 2007 Ayuu Anak Labworoye à LEGENDà à LAYAMO Nam Okora $Z Moyo Koboko Kaabong District Border Yumbe Kitgum Maracha Paibony Adjumani Kotido AMIDA Arua PADER Gulu Abim Amuru Layamo Moroto $Z Nebbi à Oyam Lira Sub County Border Amuria Lapana Buliisa Guda Masindi Apac Dokolo à Kaberamaido Katakwi Nakapiripirit Amolatar à Soroti Kumi Hoima Kapchorwa Nakasonola Bukedea Pallisa Bukwa Nakaseke Kamuli BudakaSironko Kaliro Bududa Bundibugyo Kiboga Kibaale Kayunga ButaleMjabale Namutumba Manafwa Luwero Road Network OROM Kyenjojo Iganga Tororo Kabarole Mubende Jinja Busia Lukwor Bugiri Mityana Mayuge Pawena KITGUM TC Kamwenge Kampala Lumule Kasese Panykel Akwan$Zg à NAMOKORA Sembabule Mpigi Wakiso à Ibanda Mukono à à Lyantonde Bushenyi Kiruhura Major Rivers $ZOmiya-Anyima Masaka Mbarara Kalangala Rukungiri Rakai Kitgum Matidi Kanungu Isingiro Opette $Z Ntungamo Amid$Za à KisoKraobale Protected Areas Lamit tum Lamola àAlel Pàawidi à à à Teso Bar Aparo Hil $Z IDP Camp $ZOryang à PAIMOL Okidài KACHERI à Settlement Site Lagoro àDure Akuna Làab $Z OMIYA- ANYIMA AKWANG Degazzetted Camp Lakwor $ZOmia-Pacha c PALABEK GEM à Laber Bàul KOTIDO DISTRICT KITGUM DISTRICT $ZAcholibur $ZWol $ZPaimol Mutu LAGUTI àLajeng $ZLatanya àLamin Nyi àOkinga ALEREK PALARO ACHOLIBUR Toromàa WOL Lagu$Zti Amilobo Bur Lobo à $ZPorogali Kokil à Ku Ywee à àOtok P/S Amoko à AWACH Awal à à àApil $ZKalongo -

Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR13907 Implementation Status & Results Uganda Second Northern Uganda Social Action Fund Project (NUSAF2) (P111633) Operation Name: Second Northern Uganda Social Action Fund Project Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 8 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 03-May-2014 (NUSAF2) (P111633) Public Disclosure Authorized Country: Uganda Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 28-May-2009 Original Closing Date 31-Aug-2014 Planned Mid Term Review Date 30-Jan-2012 Last Archived ISR Date 19-Nov-2013 Effectiveness Date 25-Nov-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Aug-2014 Actual Mid Term Review Date 14-Jun-2013 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) To improve access of beneficiary households in Northern Uganda to income earning opportunities and better basic socio-economic services. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Livelihood Investment Support 60.00 Community Infrastructure Rehabilitation 30.00 Institutional Development 10.00 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Moderately Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Risk Rating Implementation Status Overview The NUSAF II project originally planned to finance 9750 (i.e. 8000 Household Income Support (HIS), 1000 Public Works (PW) and 750 Community Infrastructure Rehabilitation) sub projects in the five year of its implementation period. As of February 3, 2013 a total of 8,764 subprojects (i.e. -

ABIM DISTRICT Family Planning - Costed Implementation Plan 2018/19 - 2022/23

REPUBLIC OF UGANDA ABIM DISTRICT Family Planning - Costed Implementation Plan 2018/19 - 2022/23 JUNE 2018 ABIM DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT This District Family Planning Costed Implementation Plan has been made possible with the technical support from the Ministry of Health and the United Nations Population Fund through Abim District Health Office. This project was funded by UK aid from the UK government. Published by: Abim District Local Government Ownership: Reproduction of this plan for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without permission from the Abim District Local Government, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Preferred Citation: Abim District (2018). District Family Planning Costed Implementation Plan, 2018/19-2022/23. Abim, Uganda Copies available from: Abim District Health Office. iv Table of Contents FOREWORD vii PREFACE viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix ACRONYMS x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xi SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 2 1.1 Why Should Abim District Invest in Family Planning? 3 1.2 Rationale for and use of the FP CIP 4 1.3 Key Issues and Challenges 10 SECTION TWO: SWOT ANALYSIS 19 SECTION THREE: PROCESS OF DEVELOPING THE DISTRICT FP CIP 21 SECTION FOUR: TRANSLATION OF KEY ISSUES INTO STRATEGY 23 SECTION FIVE: MODELLING ACHIEVABLE mCPR GOAL FOR ABIM DISTRICT 25 SECTION SIX: INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR IMPLEMENTATION 29 6.1 Management, Coordination, and Accountability Structure 30 6.2 Roles and Responsibilities of Key Actors (District Level) 30 6.3 Coordination Framework 30 6.4 Resource Mobilization -

Funding Going To

% Funding going to Funding Country Name KP‐led Timeline Partner Name Sub‐awardees SNU1 PSNU MER Structural Interventions Allocated Organizations HTS_TST Quarterly stigma & discrimination HTS_TST_NEG meetings; free mental services to HTS_TST_POS KP clients; access to legal services PrEP_CURR for KP PLHIV PrEP_ELIGIBLE Centro de Orientacion e PrEP_NEW Dominican Republic $ 1,000,000.00 88.4% MOSCTHA, Esperanza y Caridad, MODEMU Region 0 Distrito Nacional Investigacion Integral (COIN) PrEP_SCREEN TX_CURR TX_NEW TX_PVLS (D) TX_PVLS (N) TX_RTT Gonaives HTS_TST KP sensitization focusing on Artibonite Saint‐Marc HTS_TST_NEG stigma & discrimination, Nord Cap‐Haitien HTS_TST_POS understanding sexual orientation Croix‐des‐Bouquets KP_PREV & gender identity, and building Leogane PrEP_CURR clinical providers' competency to PrEP_CURR_VERIFY serve KP FY19Q4‐ KOURAJ, ACESH, AJCCDS, ANAPFEH, APLCH, CHAAPES, PrEP_ELIGIBLE Haiti $ 1,000,000.00 83.2% FOSREF FY21Q2 HERITAGE, ORAH, UPLCDS PrEP_NEW Ouest PrEP_NEW_VERIFY Port‐au‐Prince PrEP_SCREEN TX_CURR TX_CURR_VERIFY TX_NEW TX_NEW_VERIFY Bomu Hospital Affiliated Sites Mombasa County Mombasa County not specified HTS_TST Kitui County Kitui County HTS_TST_NEG CHS Naishi Machakos County Machakos County HTS_TST_POS Makueni County Makueni County KP_PREV CHS Tegemeza Plus Muranga County Muranga County PrEP_CURR EGPAF Timiza Homa Bay County Homa Bay County PrEP_CURR_VERIFY Embu County Embu County PrEP_ELIGIBLE Kirinyaga County Kirinyaga County HWWK Nairobi Eastern PrEP_NEW Tharaka Nithi County Tharaka Nithi County -

Abim District

National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles Abim District April 2017 National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles – Abim District This report presents findings of National Population and Housing Census (NPHC) 2014 undertaken by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Additional information about the Census may be obtained from the UBOS Head Office, Statistics House. Plot 9 Colville Street, P. O. Box 7186, Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: +256-414 706000 Fax: +256-414 237553; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.ubos.org Cover Photos: Uganda Bureau of Statistics Recommended Citation Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2017, The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Area Specific Profile Series, Kampala, Uganda. National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles – Abim District FOREWORD Demographic and socio-economic data are useful for planning and evidence-based decision making in any country. Such data are collected through Population Censuses, Demographic and Socio-economic Surveys, Civil Registration Systems and other Administrative sources. In Uganda, however, the Population and Housing Census remains the main source of demographic data, especially at the sub-national level. Population Census taking in Uganda dates back to 1911 and since then the country has undertaken five such Censuses. The most recent, the National Population and Housing Census 2014, was undertaken under the theme ‘Counting for Planning and Improved Service Delivery’. The enumeration for the 2014 Census was conducted in August/September 2014. The Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) worked closely with different Government Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) as well as Local Governments (LGs) to undertake the census exercise.