Mills, Leander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domart En P. - Doullens

Ligne 725 A Départ NAOURS WARGNIES HAVERNAS CANAPLES Arrivée FIEFFES MONTRELET BONNEVILLE BEAUVAL DOULLENS NAOURS NAOURS - DOULLENS Ligne 725 C CRAMONT - BERNAVILLE - WARGNIES HAVERNAS CANAPLES Départ CRAMONT FIEFFES MONTRELET MESNIL DOMQUEUR DOMLEGER LONGVILLERS AGENVILLE BONNEVILLE PROUVILLE Arrivée BEAUMETZ BEAUVAL BERNAVILLE DOULLENS DOULLENS CRAMONT MESNIL DOMQUEUR Conseils de lecture 1. Trouvez la ligne correspondant DOMLEGER à votre commune de départ LONGVILLERS 2. Trouvez la colonne correspondant à votre commune d'arrivée AGENVILLE 3. A l'intersection des 2, identifiez la zone tarifaire à laquelle PROUVILLE correspond votre trajet DOULLENS 4. Référez-vous à la page suivante pour connaître le tarif BEAUMETZ correspondant BERNAVILLE Ligne 725 B HALLOY LES P. -DOMART EN P. - DOULL DOULLENS Tarif A Tarif B Départ Conseils de lecture HALLOY LES PERNOIS 1. Trouvez la ligne correspondant à votre commune de départ PERNOIS BERTEAUCOURT LES 2. Trouvez la colonne DAMES correspondant à votre commune ST LEGER LES DOMART Arrivée d'arrivée DOMART EN PONTHIEU 3. A l'intersection des 2, identifiez BERNEUIL la zone tarifaire à laquelle FIENVILLERS correspond votre trajet CANDAS 4. Référez-vous à la page DOULLENS suivante pour connaître le tarif HALLOY LES PERNOIS PERNOIS Ligne 725 D HERISSART - BEAUQUESNE - DOU BERTEAUCOURT LES DAMES Tarif A Tarif B ST LEGER LES DOMART Départ DOMA T EN O THI U HERISSART R P N E TOUTENCOURT PUCHEVILLERS BERNEUIL RAINCHEVAL BEAUQUESNE Arrivée ENS TERRASMESNIL FIENVILLERS DOULLENS CANDAS HERISSART DOULLENS TOUTENCOURT PUCHEVILLERS RAINCHEVAL BEAUQUESNE TERRASMESNIL LLENS DOULLENS TARIFS trans’80 Valables du 02/09/2019 au 31/12/2019 1. Identifiez la zone tarifaire de votre trajet zone A , pour un trajet court ; zone B , pour un trajet moyen ; zone C , pour un trajet long. -

Annexe CARTOGRAPHIQUE

S S R R R !" R $%&''()(* , R R - ! R - R - ". 0E -F 3R -, R (4- - '. 5 R R , , R 2 MM Le territoire du SAGE de l'Authie 1 Le Fliers L 'Au thie La Grouches ne en ili K L a La G é z a in c o u r to Entités géographiques Occupation du sol is e L'Authie et ses affluents Broussailles Limite du bassin hydrographique de l'Authie Bâti Pas-de-Calais Eau libre Somme Forêt Sable, gravier Zone d'activités 05 10 Km Masses d'eau et réseau hydrographique réseau et d'eau Masses Masse d'eau côtière et de transition CWSF5 transition de et côtière d'eau Masse Masse d'eau de surface continentale 05 continentale surface de d'eau Masse Masse d'eau souterraine 1009 : Craie de la vallée d vallée la de Craie : 1009 souterraine d'eau Masse L'Authie et ses affluents ses et L'Authie Le Fli ers e l'Authie e l Les masses d'eau concernant le territoire territoire le concernant d'eau masses Les ' A u t h i e du SAGE de l'Authie de SAGE du la Gézaincourtoise l a G r o u c h 0 10 l e a s K il ie n n 5 Km e 2 Les 156 communes du territoire du SAGE de l'Authie (arrêté préfectoral du 5 août 1999) et la répartition de la population 14 3 AIRON-NOTRE-DAME CAMPIGNEULLES-LES-GRANDES AIRON-SAINT-VAAST RANG-DU-FLIERS BERCK BOISJEAN WAILLY-BEAUCAMP VERTON CAMPAGNE-LES-HESDIN BUIRE-LE-SEC GROFFLIERS WABEN LEPINE GOUY-SAINT-ANDRE ROUSSENT CONCHIL-LE-TEMPLE MAINTENAY SAINT-REMY-AU-BOIS NEMPONT-SAINT-FIRMIN TIGNY-NOYELLE SAULCHOY CAPELLE-LES-HESDIN -

Mairie De DOULLENS

Transports Scolaires - année 2011/2012 DOULLENS Page 1/51 Horaires valables au mardi 30 août 2011 Transports Scolaires - année 2011/2012 ECOLE PUBLIQUE ETIENNE MARCHAND (DOULLENS) Ligne: 4-02-106 - Syndicat scolaire: BERNAVILLOIS (C.C.) - Sens: Aller - Transporteur: SOCIETE CAP Fréquence Commune Arrêt Horaire Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BERNAVILLE COLLEGE DU BOIS L'EAU 08:15 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BERNAVILLE PHARMACIE 08:18 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve FIENVILLERS ECOLE 08:25 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve CANDAS RUE DE DOULLENS 08:30 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve DOULLENS ECOLE ETIENNE MARCHAND 08:39 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve DOULLENS COLLEGE JEAN ROSTAND 08:40 Ligne: 4-03-106 - Syndicat scolaire: DOULLENNAIS (C.C.) - Sens: Aller - Transporteur: SOCIETE CAP Fréquence Commune Arrêt Horaire Lu-Ma-Je-Ve OCCOCHES ABRI 08:03 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve OUTREBOIS CENTRE 08:06 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve OUTREBOIS RUE DU HAUT 08:07 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve MEZEROLLES MONUMENT AUX MORTS 08:12 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve REMAISNIL ABRI R.D. 128 08:15 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BARLY PLACE 08:20 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve NEUVILLETTE PLACE 08:25 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BOUQUEMAISON PLACE 08:30 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve DOULLENS RANSART 08:35 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve DOULLENS HAUTE VISEE 08:40 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve DOULLENS ECOLE ETIENNE MARCHAND 08:45 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve DOULLENS COLLEGE JEAN ROSTAND 08:50 Ligne: 4-03-118 - Syndicat scolaire: DOULLENNAIS (C.C.) - Sens: Aller - Transporteur: SOCIETE CAP Fréquence Commune Arrêt Horaire Lu-Ma-Je-Ve HEM-HARDINVAL CENTRE 07:58 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve LONGUEVILLETTE CENTRE 08:14 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BEAUVAL RUE DE CREQUI 08:27 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BEAUVAL ECOLE PRIMAIRE 08:29 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve BEAUVAL BELLEVUE 08:31 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve GEZAINCOURT BAGNEUX 08:39 Lu-Ma-Je-Ve GEZAINCOURT -

Cahier Des Charges De La Garde Ambulanciere

CAHIER DES CHARGES DE LA GARDE AMBULANCIERE DEPARTEMENT DE LA SOMME Document de travail SOMMAIRE PREAMBULE ............................................................................................................................. 2 ARTICLE 1 : LES PRINCIPES DE LA GARDE ......................................................................... 3 ARTICLE 2 : LA SECTORISATION ........................................................................................... 4 2.1. Les secteurs de garde ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2. Les lignes de garde affectées aux secteurs de garde .................................................... 4 2.3. Les locaux de garde ........................................................................................................ 5 ARTICLE 3 : L’ORGANISATION DE LA GARDE ...................................................................... 5 3.1. Elaboration du tableau de garde semestriel ................................................................... 5 3.2. Principe de permutation de garde ................................................................................... 6 3.3. Recours à la garde d’un autre secteur ............................................................................ 6 ARTICLE 4 : LES VEHICULES AFFECTES A LA GARDE....................................................... 7 ARTICLE 5 : L'EQUIPAGE AMBULANCIER ............................................................................. 7 5.1 L’équipage ....................................................................................................................... -

2013-10-01 Natation Doullens

18/01/2018 2013-10-01 Natation Doullens DECONNEXION A A A RECHERCHER RECHERCHER Recherche... 2013-10-01 NATATION DOULLENS Agrément Natation DOULLENS 1 octobre 2013 CPC N. CLEMENT S. FOURE Validation Nom Prénom Date de naissance Adresse Ecole Circonscription OUI NON ACCUEIL L'ÉQUIPE EPS1 TEXTES ET DOCUMENTS AGRÉMENTS ACTIVITÉS PHYSIQUES DE LA BLUXIERE Sarah 04/02/1977 3 grande ruelle 80750 CANDAS Candas Doullens X BRASSARD Céline 17/07/1973 26 rue de l’Abbaye 80370 Prouville Agenville Doullens X BARTKOWIAK Daniel 17/03/1957 2 grande rue 62270 BONNIERES Candas Doullens X 30 rue des Jonquilles Résidence Paravin 80600 THUILLIER Stéphanie 16/05/1978 Tivoli Doullens X DOULLENS http://epsold.dsden80.ac-amiens.fr/index.php/l-equipe-eps1/acces-reserve-equipe-eps1/agrements-pour-equipe/liste-natation/110-2013-10-01-natation-doullens 1/3 18/01/2018 2013-10-01 Natation Doullens LEMAIRE Audrey 08/09/1986 18 rue du Valheureux 80750 CANDAS Candas Doullens X Lavarenne MAILLARD Sophie 28/04/1988 38 avenue Flandres dunkerque 80600 DOULLENS Doullens X DOULLENS Lavarenne GLAVIEUX Céline 03/05/1986 5 place eugène andrieu 80600 DOULLENS Doullens X DOULLENS DASSONVILLE Thomas 22/04/1979 12 rue du Franc marché 80600 LUCHEUX Lucheux Doullens X DE VOGELAERE Marie-cécile 19/01/1977 23 rue St Antoine 80600 Beauquesne Beauquesne Doullens X GENSUSZ Stéphanie 08/11/1975 1 rue Verte 80620 Berneuil Bernaville Doullens X ELOBBADI Karim 26/09/1981 467 route de Bapaume 80300 POZIERES RPI Ovillers / Pozières Doullens X MONIAUX Christelle 15/08/1975 12 route de Bapaume 80300 -

Département De La Somme Enquête Publique Unique Présentée Par La

p. 1 Département de la Somme Enquête publique unique présentée par La Communauté de Communes du Territoire Nord Picardie (CCTNP) portant sur • L’élaboration du Plan Local d’Urbanisme intercommunal (PLUi) du Bernavillois, valant programme local de l’habitat • Le Règlement Local de Publicité Intercommunal (RLPi) Période d’enquête du 19 juin au 20 juillet 2017 sur une période de 32 jours Prescrite par arrêté De Monsieur le Président de la CCTPN en date du 10 mai 2017 Rapport d’enquête présenté par le commissaire-enquêteur désigné par Ordonnance n° E1700006080 du 04/04/2017, modifié le 18/05/2017, de Monsieur le Président du Tribunal administratif d’Amiens M. Bernard GUILBERT Commissaire-enquêteur. Elaboration du Plan local d’urbanisme intercommunal (PLUi) du Bernavillois Enquête publique n° E17000060/80 p. 2 Table des matières I. GENERALITES CONCERNANT LE PROJET SOUMIS A ENQUETE PUBLIQUE ............................................ 5 A. Objet de l’enquête publique ............................................................................................................................. 5 B. Cadre réglementaire......................................................................................................................................... 5 C. Composition du dossier .................................................................................................................................... 6 D. Nature et caractéristiques du projet de PLUi du Bernavillois .......................................................................... -

Taux De La Taxe Aménagement 2019-2020

BEHENCOURT BEHEN BECQUIGNY BECORDEL-BECOURT BEAUVAL BEAUQUESNE BEAUMONT-HAMEL BEAUMETZ BEAUFORT-EN-SANTERRE BEAUCOURT-SUR-L'HALLUE BEAUCOURT-SUR-L'ANCRE BEAUCOURT-EN-SANTERRE BEAUCHAMPS BEAUCAMPS-LE-VIEUX BEAUCAMPS-LE-JEUNE BEALCOURT BAZENTIN BAYONVILLERS BAYENCOURT BAVELINCOURT BARLY BARLEUX BALATRE BAIZIEUX BAILLEUL BACOUEL-SUR-SELLE AYENCOURT AVESNES-CHAUSSOY AVELUY AVELESGES AUTHUILLE AUTHIEULE AUTHIE AUTHEUX AUMONT AUMATRE AULT AUCHONVILLERS AUBVILLERS AUBIGNY AUBERCOURT ATHIES ASSEVILLERS ASSAINVILLERS ARVILLERS ARRY ARREST ARQUEVES ARMANCOURT ARGUEL ARGOULES ARGOEUVES ANDECHY ANDAINVILLE AMIENS ALLONVILLE ALLERY ALLENAY ALLAINES ALBERT AIZECOURT-LE-HAUT AIZECOURT-LE-BAS AIRAINES AILLY-SUR-SOMME AILLY-SUR-NOYE AILLY-LE-HAUT-CLOCHER AIGNEVILLE AGENVILLERS AGENVILLE ACHEUX-EN-VIMEU ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS ABLAINCOURT-PRESSOIR ABBEVILLE Commune sous le tableau)sous coordonnées des services « fiscalité » Instructeur Service STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS STSHS DDTM STPM STPM STPM STPM STPM STPM STPM STPM STPM STPM STPM STPM STPM STPM STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA STGA (voir (voir Renonciation 3,00% 0,00% 0,00% 3,00% 1,00% 2,50% 0,00% 0,00% 3,00% 0,00% 2,00% 3,00% 1,00% 0,00% 3,00% 5,00% 0,00% 3,00% 1,00% 0,00% 3,00% 0,00% 1,00% 0,00% 3,00% 0,00% 0,00% 1,00% 3,00% 2,00% 2,00% 3,00% 0,00% -

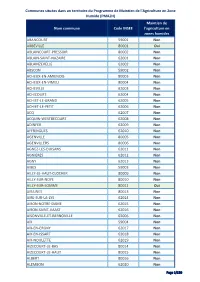

(PMAZH) Nom Commune Code INSEE

Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ABANCOURT 59001 Non ABBEVILLE 80001 Oui ABLAINCOURT-PRESSOIR 80002 Non ABLAIN-SAINT-NAZAIRE 62001 Non ABLAINZEVELLE 62002 Non ABSCON 59002 Non ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 Non ACHEUX-EN-VIMEU 80004 Non ACHEVILLE 62003 Non ACHICOURT 62004 Non ACHIET-LE-GRAND 62005 Non ACHIET-LE-PETIT 62006 Non ACQ 62007 Non ACQUIN-WESTBECOURT 62008 Non ADINFER 62009 Non AFFRINGUES 62010 Non AGENVILLE 80005 Non AGENVILLERS 80006 Non AGNEZ-LES-DUISANS 62011 Non AGNIERES 62012 Non AGNY 62013 Non AIBES 59003 Non AILLY-LE-HAUT-CLOCHER 80009 Non AILLY-SUR-NOYE 80010 Non AILLY-SUR-SOMME 80011 Oui AIRAINES 80013 Non AIRE-SUR-LA-LYS 62014 Non AIRON-NOTRE-DAME 62015 Non AIRON-SAINT-VAAST 62016 Non AISONVILLE-ET-BERNOVILLE 02006 Non AIX 59004 Non AIX-EN-ERGNY 62017 Non AIX-EN-ISSART 62018 Non AIX-NOULETTE 62019 Non AIZECOURT-LE-BAS 80014 Non AIZECOURT-LE-HAUT 80015 Non ALBERT 80016 Non ALEMBON 62020 Non Page 1/130 Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ALETTE 62021 Non ALINCTHUN 62022 Non ALLAINES 80017 Non ALLENAY 80018 Non ALLENNES-LES-MARAIS 59005 Non ALLERY 80019 Non ALLONVILLE 80020 Non ALLOUAGNE 62023 Non ALQUINES 62024 Non AMBLETEUSE 62025 Oui AMBRICOURT 62026 Non AMBRINES 62027 Non AMES 62028 Non AMETTES 62029 Non AMFROIPRET 59006 Non AMIENS 80021 Oui AMPLIER 62030 Non AMY -

MOUVEMENT SEPTEMBRE 2014 - 1Ère PHASE ALPHABETIQUE

MOUVEMENT SEPTEMBRE 2014 - 1ère PHASE ALPHABETIQUE A ADOLPHE MAITE AMIENS, DSDEN DE LA SOMME TIT.R.BRIG SANS SPEC. AHITCHEME AURELIA SANS AFFECTATION ANCELET ADELINE MUILLE VILLETTE, E.E.PU ENS.CL.ELE SANS SPEC. ANCELLIN KAREN AMIENS, E.E.PU EDMOND ROSTAND INI.ET.ELE PRIMO ARRI ANDRE AMANDINE SANS AFFECTATION ANDRE ISABELLE ABBEVILLE, E.M.PU JEAN MOULIN ENS.CL.MA SANS SPEC. ANDRET SOPHIE AMIENS, E.E.PU SAINT-ROCH B ENS.CL.ELE SANS SPEC. ANDRIEUX MYLENE DOMART EN PONTHIEU, E.E.PU (VZ3 DOULLENS, BRIGADE) TIT.R.BRIG SANS SPEC. ANSELME JEAN-PAUL CORBIE, E.E.PU DU CENTRE DIR.EC.ELE 11 CLASSES ANTIOCHUS AGATHE HOMBLEUX, E.E.PU LOUIS SCLAVIS ENS.CL.ELE SANS SPEC. AOUAD ILHAM AMIENS, CLG GUY MARESCHAL CL. RELAIS INSTIT SES ASQUIN LAURENCE AMIENS, E.M.PU FAFET (VC AMIENS, MAT) ENS.CL.MA SANS SPEC. AUBRY SANDRINE AMIENS, E.E.PU FG DE BEAUVAIS ENS.CL.ELE SANS SPEC. AZARHOOSHANG SAADIA AMIENS, E.E.PU ETOUVIE GROUPE B TP CLIS.1.MEN OPTION D B BACHELET CLAIRE SANS AFFECTATION BARBAZAN VINCENT BOVES, E.E.PU LES DEUX VALLEES DECH DIR SANS SPEC. 25% BARBAZAN VINCENT CAMON, E.E.PU PAUL LANGEVIN DECH DIR SANS SPEC. 25% BARBAZAN VINCENT LONGUEAU, E.E.PU ANDRE MILLE DECH DIR SANS SPEC. 25% BARBAZAN VINCENT LONGUEAU, E.E.PU PAUL BAROUX DECH DIR SANS SPEC. 25% BAUDIMONT ADELINE AMIENS, E.M.PU FAUBOURG DE HEM ENS.CL.ELE SANS SPEC. BAYART ALAIN AMIENS, E.E.PU LES VIOLETTES ENS.CL.ELE SANS SPEC. -

Fumées De L'incendie De L'usine Lubrizol Ayant

Amiens, le 2 octobre 2019 Communiqué de presse Fumées de l’incendie de l’usine Lubrizol ayant traversé le département de la Somme Les mesures de précaution sont adaptées et le périmètre des communes qui y sont soumises reste inchangé A la suite de l’incendie de l’usine Lubrizol à Rouen le 26 septembre dernier, des fumées ont traversé le département de la Somme suivant un axe Nord/Nord-Est entre le jeudi 26 septembre au matin et le vendredi 27 septembre au soir. Le périmètre de l’arrêté du 29 septembre 2019 reste inchangé. Des contrôles réalisés le 29 septembre dans les communes du département ont fait apparaître des traces de suie dans 39 communes. Les nouveaux signalements de communes ont fait l’objet de plusieurs vérifications qui n’ont pas permis de confirmer la présence de suies. Le nombre de communes impactées demeure donc inchangé à ce jour. Les mesures de précautions sont adaptées. Les mesures prises le 29 septembre qui limitaient certaines activités agricoles et la mise sur le marché de produits alimentaires d'origine animale et végétale sont modifiées par arrêté préfectoral du 2 octobre 2019. Les adaptations et clarifications apportées visent : • à autoriser de poursuivre la récolte de végétaux à condition de les tracer, de les identifier et de les conserver de façon séparée sur l’exploitation ; • à rappeler que ne sont pas concernées par les mesures de l’arrêté (i) les cultures de végétaux non exposés aux retombées de suies, en particulier les productions sous serre ou sous tunnel, et (ii) les denrées issues d’animaux non exposés aux retombées de suies et qui ont été alimentés par des aliments non exposés. -

Votre Hebdomadaire Dans La Somme

Votre hebdomadaire dans la Somme Fort-Mahon- Le Journal d'Abbeville Plage Nampont Argoules Parution : mercredi Dominois Quend Villers- sur-Authie Vron Ponches- Estruval Vercourt Vironchaux Dompierre- Saint- Regnière- sur- Quentin- Ecluse Ligescourt Authie en-Tourmont Arry Rue Machy Machiel Bernay- Le Boisle en-Ponthieu Estrées- Boufflers lès-Crécy Le Forest- Vitz- Crotoy Montiers Crécy- sur-Authie en-Ponthieu Fontaine- Gueschart Favières sur-Maye Brailly- Cornehotte Neuilly- Froyelles le-Dien Ponthoile Bouquemaison Nouvion Noyelles- Maison- Frohen- Brévillers Forest- en-Chaussée Ponthieu le-Grand l'Abbaye Humbercourt Domvast Béalcourt Remaisnil Barly Neuvillette Hiermont Maizicourt Saint- Noyelles- Frohen- Lucheux Lamotte- Canchy Acheul Saint- sur-Mer Le Titre Bernâtre le-Petit Lanchères Buleux Yvrench Grouches- Gapennes Montigny- Luchuel Valéry- Sailly- Conteville Mézerolles Occoches Flibeaucourt Agenvillers les-Jongleurs Le sur-Somme Hautvillers- Neuilly- Yvrencheux Agenville Meillard Cayeux- Ouville l'Hôpital Outrebois sur-Mer Pendé Boismont Domléger- Heuzecourt Doullens Port-le-Grand Buigny- Longvillers Estrébœuf Saint- Millencourt- Oneux Boisbergues Hem- Cramont Prouville Hardinval Maclou Drucat en-Ponthieu Brutelles Saigneville Coulonvillers Authieule Saint- Autheux Gézaincourt Grand- Mesnil- Beaumetz Blimont Arrest Caours Maison- Bernaville Mons- Laviers Saint- Domqueur Saint- Bayencourt Boubert Roland Longuevillette Woignarue Riquier Domesmont Authie Léger- Cahon Neufmoulin lès- Coigneux Vaudricourt Ribeaucourt Fienvillers Quesnoy- -

757 Cramont – Bernaville – Amiens Horaires Valables Jusqu'au 30 Avril 2021

757 CRAMONT – BERNAVILLE – AMIENS HORAIRES VALABLES JUSQU'AU 30 AVRIL 2021 PETITES VACANCES PETITES VACANCES Jours de circulation LMmJVS LMmJVS mS Jours de circulation mS LMmJVS 57100 57146 57516 57246 57376 CRAMONT Mairie 06:10 08:40 12:45 AMIENS Gare Routière 12:15 18:00 MESNIL DOMQUEUR Rue des Tilleuls 06:15 08:45 12:50 AMIENS Arrêt AMETIS Voltaire 12:20 18:05 DOMLEGER LONGVILLERS Longvillers - Rue Dacquet 06:18 08:48 12:53 AMIENS Arrêt AMETIS Dunlop 12:25 18:10 DOMLEGER LONGVILLERS Domléger - Rue Dorion 06:21 08:51 12:56 CANAPLES Rue de la Vicogne 12:45 18:30 AGENVILLE Eglise 06:23 08:53 12:58 FIEFFES MONTRELET Fieffes 12:48 18:33 PROUVILLE Place de la Mairie 06:25 08:55 13:00 FIEFFES MONTRELET Montrelet 12:49 18:34 BEAUMETZ Eglise 06:29 08:59 13:04 BONNEVILLE Salle des fêtes 12:52 18:37 BERNAVILLE Achille Monflier 06:33 09:03 13:08 CANDAS Salle polyvalente 12:59 18:44 BERNAVILLE Eglise 06:34 09:04 13:09 FIENVILLERS Mairie 13:04 18:49 BERNAVILLE Route Nationale 06:35 09:05 13:10 BERNAVILLE Route Nationale 13:10 18:55 FIENVILLERS Mairie 06:41 09:11 13:16 BERNAVILLE Eglise 13:11 18:56 CANDAS Salle polyvalente 06:46 09:16 13:21 BERNAVILLE Achille Monfliers 13:12 18:57 BONNEVILLE Salle des fêtes 06:53 09:23 13:28 BEAUMETZ Eglise 13:16 19:01 FIEFFES MONTRELET Montrelet 06:56 09:26 13:31 PROUVILLE Place de la Mairie 13:20 19:05 FIEFFES MONTRELET Fieffes 06:57 09:27 13:32 AGENVILLE Eglise 13:22 19:07 CANAPLES Rue de la Vicogne 07:00 09:30 13:35 DOMLEGER LONGVILLERS Domléger - Rue Dorion 13:24 19:09 AMIENS Arrêt AMETIS Dunlop (1) 07:20 09:50 13:55 DOMLEGER LONGVILLERS Longvillers - Rue Dacquet 13:27 19:12 AMIENS Arrêt AMETIS Voltaire (1) 07:25 09:55 14:00 MESNIL DOMQUEUR Rue des Tilleuls 13:30 19:15 AMIENS Gare Routière 07:35 10:00 14:05 CRAMONT Mairie 13:35 19:20 Jours de circulation : L Lundi ; M Mardi ; m Mercredi ; J Jeudi ; V Vendredi ; S Samedi ; D Dimanche Attention : Les cars ne circulent pas les jours fériés (lundi de Pentecôte compris).