The Entity – Identity Relationships of Old Shop Houses in Perak Through Facade Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guideline for Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of MSW Landfill Sites

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY MINISTRY OF HOUSING AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT, MALAYSIA THE STUDY ON THE SAFE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF LANDFILL SITES IN MALAYSIA FINAL REPORT Volume 3 Guideline for Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of MSW Landfill Sites NOVEMBER 2004 YACHIYO ENGINEERING CO., LTD. EX CORPORATION The Final Report of “The Study on The Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of Landfill Sites in Malaysia” is composed of seven Volumes as shown below: Volume 1 Summary Volume 2 Main Report Volume 3 Guideline for Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of MSW Landfill Sites Volume 4 Pilot Projects on Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of Landfill Sites Volume 5 Technical Guideline for Sanitary Landfill, Design and Operation (Revised Draft, 2004) Volume 6 User Manual of LACMIS (Landfill Closure Management Information System) Volume 7 Data Book This Report is “Volume 3 Guideline for Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of MSW Landfill Sites”. Guideline for Safe Closure and Rehabilitation of MSW Landfill Sites (Draft) Part I : General Part II : Technical Requirements Appendices Ministry of Housing and Local Government MALAYSIA GUIDELINE FOR SAFE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF MSW LANDFILL SITES CONTENTS Contents Abbreviations Part I General..................................................................................................................I-1 I-1 Purpose of the Guideline·····························································································I-1 I-2 Scope of the Guideline································································································I-2 -

Perak Heads of State Department and Local Authority Directory 2020

PERAK HEADS OF STATE DEPARTMENT AND LOCAL AUTHORITY DIRECTORY 2020 DISTRIBUTION LIST NO. DESIGNATION / ADDRESS NAME OF TELEPHONE / FAX HEAD OF DEPARTMENT 1. STATE FINANCIAL OFFICER, YB Dato’ Zulazlan Bin Abu 05-209 5000 (O) Perak State Finance Office, Hassan *5002 Level G, Bangunan Perak Darul Ridzuan, 05-2424488 (Fax) Jalan Panglima Bukit Gantang Wahab, [email protected] 30000 IPOH 2. PERAK MUFTI, Y.A.Bhg. Tan Sri Dato’ Seri Haji 05-2545332 (O) State Mufti’s Office, Harussani Bin Haji Zakaria 05-2419694 (Fax) Level 5, Kompleks Islam Darul Ridzuan, Jalan Panglima Bukit Gantang Wahab, [email protected] 30000 IPOH. 3. DIRECTOR, Y.A.A. Dato Haji Asa’ari Bin 05-5018400 (O) Perak Syariah Judiciary Department, Haji Mohd Yazid 05-5018540 (Fax) Level 5, Kompleks Mahkamah Syariah Perak, Jalan Pari, Off Jalan Tun Abdul Razak, [email protected] 30020 IPOH. 4. CHAIRMAN, Y.D.H Dato’ Pahlawan Hasnan 05-2540615 (O) Perak Public Service Commission, Bin Hassan 05-2422239 (Fax) E-5-2 & E-6-2, Menara SSI, SOHO 2, Jalan Sultan Idris Shah, [email protected] 30000 IPOH. 5. DIRECTOR, YBhg. Dato’ Mohamad Fariz 05-2419312 (D) Director of Land and Mines Office, Bin Mohamad Hanip 05-209 5000/5170 (O) Bangunan Sri Perak Darul Ridzuan, 05-2434451 (Fax) Jalan Panglima Bukit Gantang Wahab, [email protected] 30000 IPOH. 6. DIRECTOR, (Vacant) 05-2454008 (D) Perak Public Works Department, 05-2454041 (O) Jalan Panglima Bukit Gantang Wahab, 05-2537397 (Fax) 30000 IPOH. 7. DIRECTOR, TPr. Jasmiah Binti Ismail 05-209 5000 (O) PlanMalaysia@Perak, *5700 Town and Country Planning Department, [email protected] 05-2553022 (Fax) Level 7, Bangunan Kerajaan Negeri, Jalan Panglima Bukit Gantang Wahab, 30000 IPOH. -

Sime Darby Plantation Berhad

PF441 RSPO P&C Public Summary Report Revision 11 (Sept 2020) RSPO PRINCIPLE AND CRITERIA PUBLIC SUMMARY REPORT ☐ Initial Assessment ☒ Annual Surveillance Assessment (1_4) ☐ Recertification Assessment (Choose an item.) ☐ Extension of Scope Client Company name (Parent Company): Sime Darby Plantation Berhad Client company Address: Level 3A, Main Block, Plantation Tower, No. 2, Jalan PJU 1A/7 47301 Ara Damansara, Selangor, Malaysia Certification Unit: Strategic Operating Unit (SOU 4) – Flemington Palm Oil Mill Location of Certification Unit: Lot 5138, Jalan Sg Dulang, Sungai Sumun 36309 Teluk Intan, Perak, Malaysia Date of Final Report: 01/01/2021 Page 1 of 196 PF441 RSPO P&C Public Summary Report Revision 11 (Sept 2020) TABLE of CONTENTS Page No Section 1: Scope of the Certification Assessment ....................................................................... 4 1. Company Details ............................................................................................................... 4 2. Certification Information .................................................................................................... 4 3. Other Certifications ............................................................................................................ 5 4. Location(s) of Mill & Supply Bases ...................................................................................... 5 5. Description of Supply Base ................................................................................................. 5 6. Plantings & Cycle .............................................................................................................. -

King in Critical Condition but Stable, Istana Negara Says

20 NOV 2001 Agong-Critical KING IN CRITICAL CONDITION BUT STABLE, ISTANA NEGARA SAYS KUALA LUMPUR, Nov 20 (Bernama) -- The Yang di-Pertuan Agong Sultan Salahuddin Abdul Aziz Shah, who is being treated further at the Gleneagles Intan medical centre here, is in critical condition but is still stable, an Istana Negara statement said today. "According to medical specialists treating his majesty, the King is now in critical condition and requires intensive care. However his majesty is still stable," said the statement signed by Istana Negara coordinator Datuk Ishak Ahmad. Sultan Salahuddin is undergoing further treatment at the medical centre since Sunday upon being treated for almost two months at the Mount Elizabeth Hospital in Singapore. "Let us all Malaysians pray to God the Almighty for his majesty's well-being and recovery," the statement said. According to the statement, Sultan Azlan Shah of Perak and the Raja Permaisuri of Perak Tuanku Bainun, the Raja Muda of Perak and the King's son the Regent of Selangor were among the Malay Rulers who visited his majesty today. Yesterday's visitors include the Deputy Yang di-Pertuan Agong Sultan Mizan Zainal Abidin and Permaisuri Nur Zahirah, the Yang Dipertuan Besar Negeri Sembilan Tuanku Ja'afar and Tuanku Ampuan Najihah, the Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad and wife Datin Seri Dr Siti Hasmah Mohamed Ali. The Menteri Besar of Selangor Datuk Seri Dr Mohamad Khir Toyo and wife Datin Zaharah Kechik had also visited the King. His majesty continued to receive a stream of visitors up till late afternoon, including members of the royalty notably his younger brother Tengku Besar Putra Azam and the Tengku Mahkota of Pahang Tengku Abdullah Sultan Ahmad Shah. -

Arms Procurement Decision Making Volume II: Chile, Greece, Malaysia

4. Malaysia Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam* I. Introduction Malaysia has become one of the major political players in the South-East Asian region with increasing economic weight. Even after the economic crisis of 1997–98, despite defence budgets having been slashed, the country is still deter- mined to continue to modernize and upgrade its armed forces. Malaysia grappled with the communist insurgency between 1948 and 1962. It is a democracy with a strong government, marked by ethnic imbalances and affirmative policies, strict controls on public debate and a nascent civil society. Arms procurement is dominated by the military. Public apathy and indifference towards defence matters have been a noticeable feature of the society. Public opinion has disregarded the fact that arms procurement decision making is an element of public policy making as a whole, not only restricted to decisions relating to military security. An examination of the country’s defence policy- making processes is overdue. This chapter inquires into the role, methods and processes of arms procure- ment decision making as an element of Malaysian security policy and the public policy-making process. It emphasizes the need to focus on questions of public accountability rather than transparency, as transparency is not a neutral value: in many countries it is perceived as making a country more vulnerable.1 It is up 1 Ball, D., ‘Arms and affluence: military acquisitions in the Asia–Pacific region’, eds M. Brown et al., East Asian Security (MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass., 1996), p. 106. * The author gratefully acknowledges the help of a number of people in putting this study together. -

Recognising Perak Hydro's

www.ipohecho.com.my FREE COPY IPOH echoechoYour Voice In The Community February 1-15, 2013 PP 14252/10/2012(031136) 30 SEN FOR DELIVERY TO YOUR DOORSTEP – ISSUE ASK YOUR NEWSVENDOR 159 Malaysian Book Listen, Listen Believe in Royal Belum Yourself of Records World Drums and Listen broken at Festival 2013 Sunway’s Lost World of Tambun Page 3 Page 4 Page 6 Page 9 By James Gough Recognising Perak Hydro’s Malim Nawar Power Staion 2013 – adaptive reuse as a training Contribution to Perak and maintenance facility adan Warisan Malaysia or the Malaysian Heritage BBody, an NGO that promotes the preservation and conservation of Malaysia’s built Malim Nawar Power Station 1950’s heritage, paid a visit recently to the former Malim Nawar Power Station (MNPS). According to Puan Sri Datin Elizabeth Moggie, Council Member of Badan Warisan Malaysia, the NGO had forwarded their interest to TNB to visit MNPS to view TNB’s effort to conserve their older but significant stations for its heritage value. Chenderoh Dam Continued on page 2 2 February 1-15, 2013 IPOH ECHO Your Voice In The Community “Any building or facility that had made a significant contribution to the development of the country should be preserved.” – Badan Warisan Malaysia oggie added that Badan Warisan was impressed that TNB had kept the to the mining companies. buildings as is and practised adaptive reuse of the facility with the locating of Its standard guideline was MILSAS and REMACO, their training and maintenance facilities, at the former that a breakdown should power station. not take longer than two Moggie added that any building or facility that had made a significant contribution hours to resume operations to the development of the country should be preserved for future generations to otherwise flooding would appreciate and that power generation did play a significant part in making the country occur at the mine. -

CBD Sixth National Report

SIXTH NATIONAL REPORT OF MALAYSIA to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) December 2019 i Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................ vi List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................... vi Foreword ..................................................................................................................................................... vii Preamble ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 3 CHAPTER 1: UPDATED COUNTRY BIODIVERSITY PROFILE AND COUNTRY CONTEXT ................................... 1 1.1 Malaysia as a Megadiverse Country .................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Major pressures and factors to biodiversity loss ................................................................................. 3 1.3 Implementation of the National Policy on Biological Diversity 2016-2025 ........................................ -

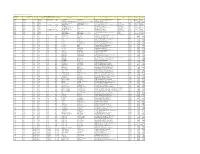

Inventory Stations in Perak 40 Jps 210 False 20 Jps 41.4 False 00 00 Jps 339 False 45 Jps 1390 False

INVENTORY STATIONS IN PERAK PROJECT STESEN STATION NO STATION NAME FUNCTION STATE DISTRICT RIVER RIVER BASIN YEAR OPEN YEAR CLOSE ISO ACTIVE MANUAL TELEMETRY LOGGER LATITUDE LONGITUDE OWNER ELEV CATCH AREA STN PEDALAMAN 3813414 Sg. Trolak di Trolak WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Trolak Sg. Bernam 1946 TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 03 53 30 101 22 45 JPS 65.8 FALSE 3814413 Sg. Slim At Kg. Slim WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Slim Sg. Bernam 1930 07/72 FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE 03 51 00 101 28 45 JPS 314 FALSE 3814415 Sg. Bil At Jln. Tg. Malim-Slim WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Bil Sg. Bernam 1946 07/83 FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 03 49 30 101 29 20 JPS 41.4 FALSE 3814416 Sg. Slim At Slim River WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Slim Sg. Bernam 11/66 TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE 03 49 35 101 24 40 JPS 455 FALSE 3901401 Sungai Bidor di Changkat Jong WL Perak Hilir Perak FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE 3.99 101.1 FALSE 3907403 Sg.Perak di Kg.Pasang Api, Bagan Datok WL Perak Hilir Perak Muara Sg. Perak FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE 3 59 17.37 100 45 55.69 FALSE 3911457 Sg. Sungkai At Jln. Anson-Kampar WL Perak Hilir Perak Sg. Sungkai Sg. Perak 1950 07/83 FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 03 59 20 101 07 30 JPS 479 FALSE 3913458 Sg. Sungkai di Sungkai WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Sungkai Sg. Perak 1930 TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE 03 59 15 101 18 50 JPS 289 FALSE 4011451 Sg. -

08 Jelonek Pulo.Qxd

108 Studia Arabistyczne i Islamistyczne 11, 2003 Adam Jelonek Integration and separatism. A sociopolitical study of the Thai government policy to the Muslim South Introduction Southern Thailand has a Muslim population with a 200 year history of separatism and evolving relations with the central government. This paper refers to Southern Thailand as the five provinces of Songkhala, Satun, Yala, Pattani, and Narathiwat which borders Malaysia. Approximately 80% of the Malay-Muslim or “Thai-Muslim” minority live in the southern provinces. Nationwide, there are nearly 4 million Muslims of the 62 million Thai pop- ulation. (Please note that the term “Malay-Muslim” and “Thai-Muslim” will be used interchangeably throughout the paper. Thai-Muslim is the term used officially by the Thai government to lessen ethnic differentiation.) Thai-Muslims have a strong, distinctive ethnic identity that is tied to their Malay ethnicity, Malay language, and Islamic faith. Language is a point of contention as it is a symbol and identification of religion. While an esti- mated 99% of Muslims speak Thai, Malay is the mother tongue for 75% of them (Yegar, 131; VIC, 2). Furthermore, in the 14th century, the five border provinces belonged to the Malay-Muslim Pattani Kingdom, which was con- sidered as the cradle of Islam in Southeast Asia (Bonura, 15). Most of the separatist tensions appear in Pattani, Narathiwat, Yala, and to a lesser extent, Satun. Songkhala has a lower concentration of Malay-Muslims, which then acts as a geographical buffer between Satun and the other three provinces. Another point of contention is socio-economic disparity, which is a charac- teristic of internally colonized states and tends to heighten regional tensions. -

The Perak Development Experience: the Way Forward

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences December 2013, Vol. 3, No. 12 ISSN: 2222-6990 The Perak Development Experience: The Way Forward Azham Md. Ali Department of Accounting and Finance, Faculty of Management and Economics Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i12/437 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i12/437 Speech for the Menteri Besar of Perak the Right Honourable Dato’ Seri DiRaja Dr Zambry bin Abd Kadir to be delivered on the occasion of Pangkor International Development Dialogue (PIDD) 2012 I9-21 November 2012 at Impiana Hotel, Ipoh Perak Darul Ridzuan Brothers and Sisters, Allow me to briefly mention to you some of the more important stuff that we have implemented in the last couple of years before we move on to others areas including the one on “The Way Forward” which I think that you are most interested to hear about. Under the so called Perak Amanjaya Development Plan, some of the things that we have tried to do are the same things that I believe many others here are concerned about: first, balanced development and economic distribution between the urban and rural areas by focusing on developing small towns; second, poverty eradication regardless of race or religion so that no one remains on the fringes of society or is left behind economically; and, third, youth empowerment. Under the first one, the state identifies viable small- and medium-size companies which can operate from small towns. These companies are to be working closely with the state government to boost the economy of the respective areas. -

GST Chat Keeping You up to Date on the Latest News in the Indirect Tax World

GST Chat – February 2018 GST Chat Keeping you up to date on the latest news in the Indirect Tax world February 2018 1 GST Chat – February 2018 Issue 2.2018 Quick links: Contact us - Our GST team Key takeaways: 1. Amendments to the Goods and Services Tax Regulation 2. New Public Ruling 3. GST Technical Updates 4. Imposition of new Customs and Excise Duties (Exemption) Order 2 GST Chat – February 2018 Greetings from Deloitte Malaysia’s Indirect Tax Team Hello everyone and welcome to the February edition of GST Chat. As we welcomed the Chinese New Year over the past week, we would like to take this opportunity to wish all of you happiness, good health and prosperity! Moving on to indirect tax developments, the Royal Malaysian Customs Department (“RMCD”) has finally released details on what needs to be reported in the new item 15 (Other Supplies) in the GST Return. This represents a significant change and impacts in the January 2018 GST Return. You can read about it in more detail in our special alert. Here is some recent news that may interest you: The RMCD have identified more than 5,000 companies that were involved in GST fraud. These companies had collected GST but had not remitted the GST collected to the RMCD. The Director General, Datuk Seri T. Subromaniam stated that the RMCD had opened investigation proceedings against all the companies involved, with a number already charged before the court. He did stress, however, that the RMCD’s broader approach to taxpayers was through a customer-friendly strategy of ‘compliance through education’ as opposed to enforcement and punitive actions. -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN